While walking the Overland Track between Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair in 1931, pedestrian extraordinaire ET Emmett found some words scribbled on a pine rafter inside the old mine workers’ hut at Pelion Plain.[1] The scribble authors, Emmett wrote, were ‘members of Mr Jocelyne’s [sic] South African party’, who had recorded details of their seven days’ stay in the area:

‘Scalps taken: Mt Oakleigh, Mr Ossa, Lake Ayr, Mt Thetis, Forth Gorge, Toad Rocks, Pelion East’.[2]

The Joscelyne in question was probably Horace Joscelyne (1878–1965), a Launceston-born grocer’s assistant who visited Cradle Mountain in 1922.[3] But who were the South Africans? Perhaps Horace and his wife Addie showed Tasmania to some South African visitors. Emmett’s 1931 Overland Track party was guided by temporary park ranger Bert Nichols, but the Joscelyne tour was probably from the time of Nichols’ predecessor as highland tour guide, Paddy Hartnett.

The Fred Smithies papers in the Tasmanian Archives[4] contain what is probably a semi-fictional account of the Joscelyne trip with Hartnett. Most of the same ‘scalps’—Mounts Oakleigh, Ossa and Thetis, Lake Eyre [sic] and ‘Pelion’s giant toad’—in the fictional account were ‘taken’ in similar order as outlined on the Pelion hut rafter. Although the story has a more linear structure than ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’ (see earlier blog), it refers to the earlier story and appears to have the same anonymous author. As outlined in the previous blog, the author of the Waldheim mailbag story is likely to be one of Vera May Scott, Lydia Morrison or Addie (Harriet Mary) Joscelyne. It is unknown whether any of these women was a member of Horace Joscelyne’s ‘South African’ party. The candidates for authorship line up like this:

Vera May Scott (1886–1962)[5] was born at Battersea, London. At the 1901 British census she was a 15-year-old living in London with her 47-year-old piano tuner father Henry Sidney Scott and 37-year-old Brisbane-born mother May Scott.[6] No record of the family’s migration was found, but in 1922 Vera May Scott was an unmarried typist living at 28 Delamere Crescent, Trevallyn with her parents and sister Eleanor Scott.[7] Scott lived next door to the Joscelynes and had a strong connection to the family. In 1945 she thanked Horace Joscelyne for ‘unfailing kindness’ during her mother’s long illness.[8] Rupert William Joscelyne Hart, whom Scott recognised in her will, was the son of Horace Joscelyne’s sister Violet Mary Joscelyne.[9]

Lydia Morrison (1886–1971)[10] appears to have emigrated from England as a small child in 1891, along with her two-year-old brother and her parents, 28-year-old Lydia Morrison senior and 35-year-old farmer William Morrison.[11] In 1922 Lydia lived with her parents, her sister Dorothy Mary Morrison and brother William Morrison junior, at 211 St John Street, Launceston.[12] Forty-six years later in 1968 Lydia was still listed as an unmarried clerk—at 82 years of age—and living with her bookbinder sister at 6 Union Street, Launceston.[13]

Harriet (‘Addie’) Joscelyne née Cumings (c1872–1946) emigrated from England with her sister as a teenaged nursemaid in 1888. Her parents, Ebenezer and Caroline Cumings, had preceded her and were already Launceston residents.[14] Addie’s older sister Minnie gave her occupation in the passenger list as schoolteacher, and until her marriage in 1893 she operated the Trevallyn Preparatory School.[15] At this point Addie Cumings took over from her, continuing the school until at least 1897.[16] This suggests that she was at least reasonably well educated. Addie Cumings married Horace Samuel Joscelyne at Launceston in 1903. They had no children.[17]

When did the trip take place?

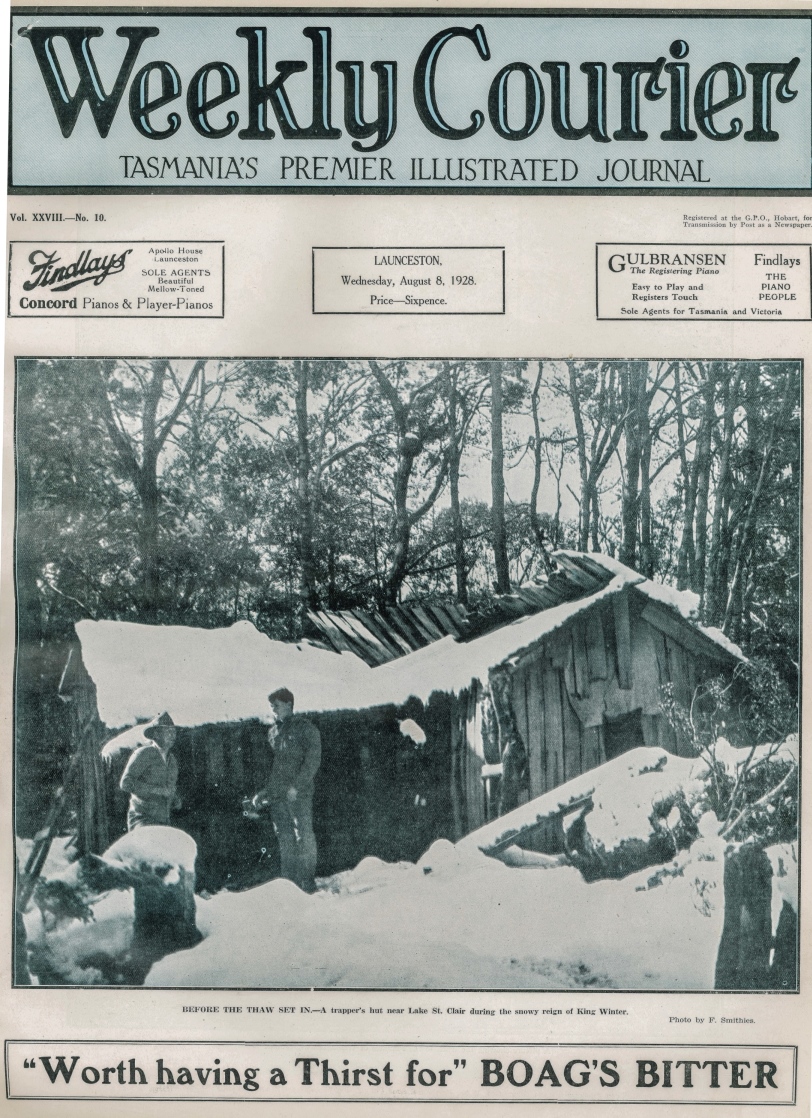

Details in the semi-fictional account allow us to arrive at a possible time for the trip on which it was based. It was undertaken when the waratahs were in flower, which makes it in the period October to December. The ‘mistress of the more pretentious hut’ mentioned in the text was Elizabeth Gregson of Gisborne’s Hut/the Mount Pelion Mines Hut. She was living alone, which puts the trip in a two-month window between the death of her partner John Gregson on 11 June 1926 and her admission to the New Town Charitable Infirmary on 5 August 1926.[18] This suggests a winter tour, a very unlikely scenario not only because of the weather conditions but because at this time Hartnett would almost certainly have been hunting out beyond Adamsfield. Clearly also this does not tally with the late spring/early summer appearance of waratah blooms! The fictional account contains a credible return visit to Gisborne’s Hut when Elizabeth was found to be ‘in most wretched and squalid sickness’, a ‘poor frail old form’ eliciting ‘a deep pity for all lonely bush women, and especially all sick ones’. This does suggest the type of situation in which the elderly widow would have been forced to enter the charitable institution. The writer has taken the liberty of moving Elizabeth Gregson’s last days of freedom into the late spring, a much more likely time for the Pelion excursion.

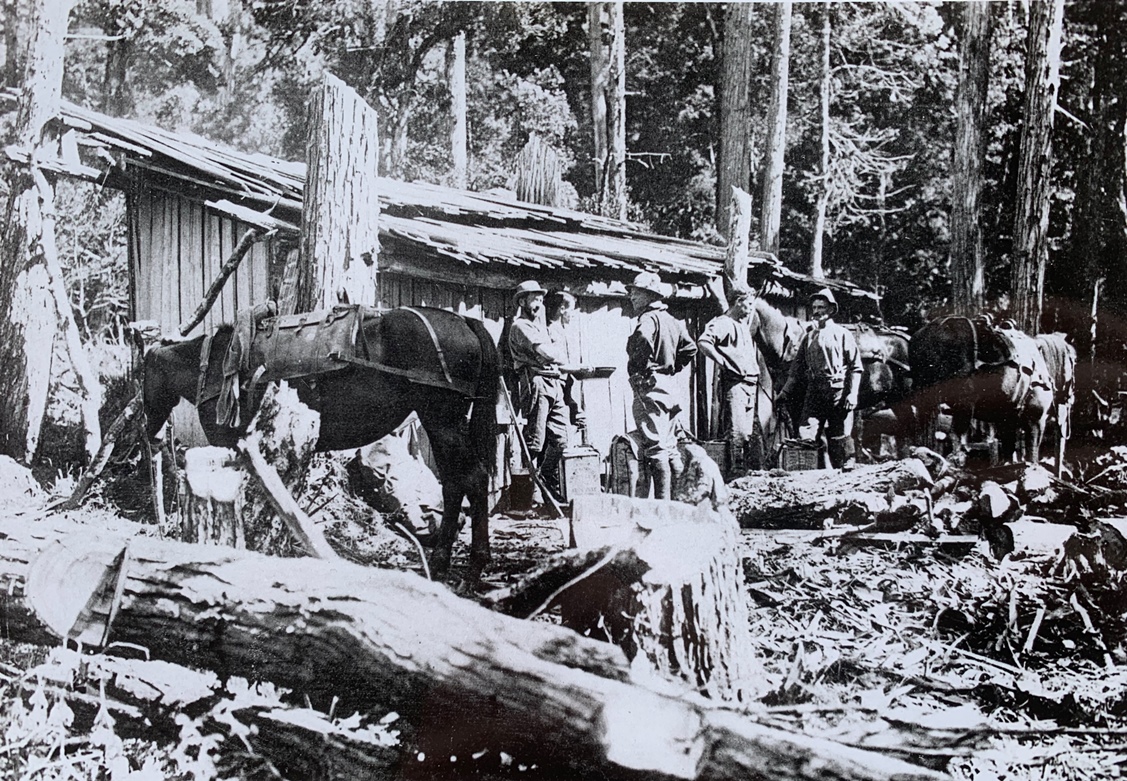

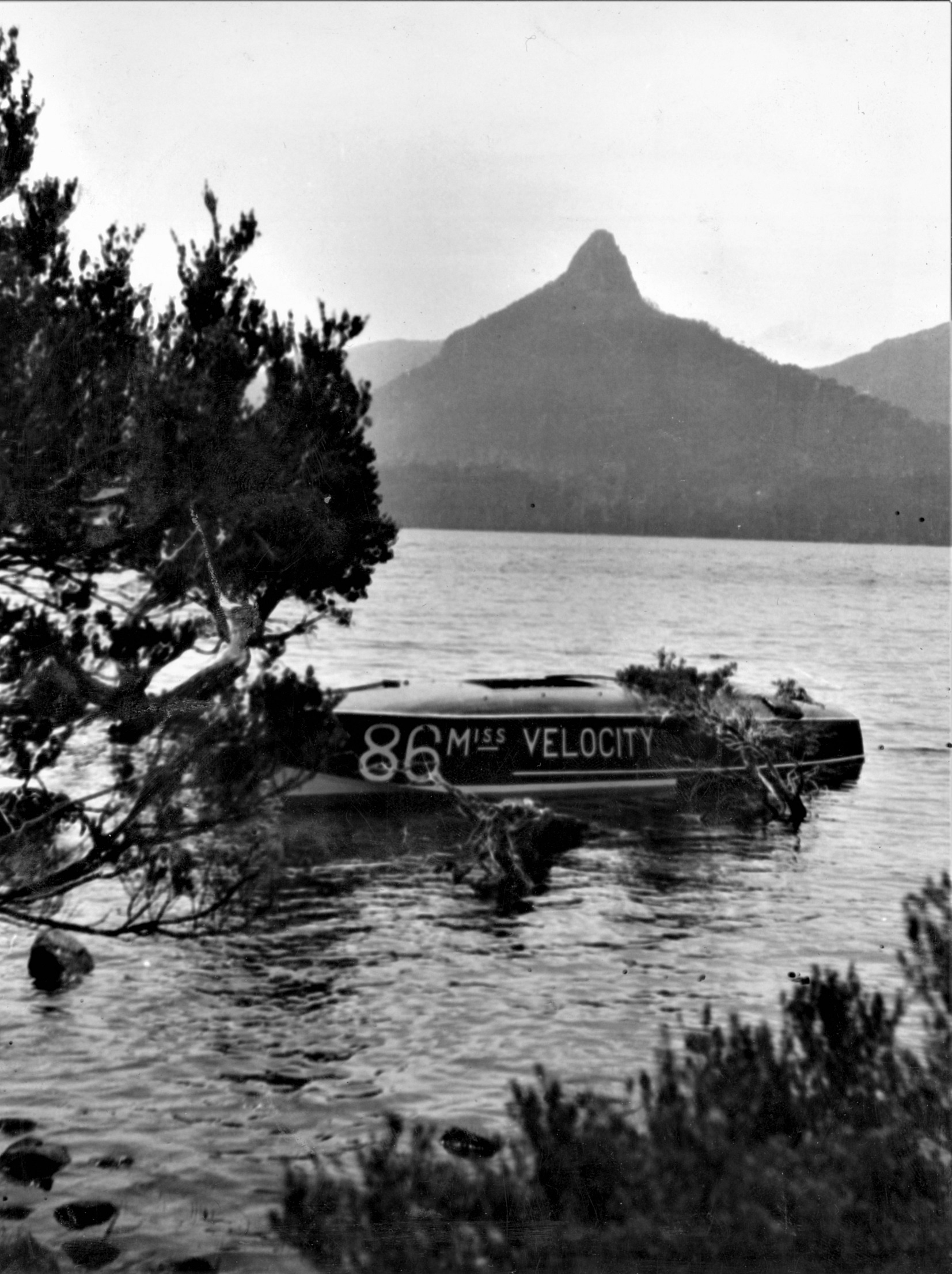

Photo courtesy of the late Nell Williams.

What about the Waldheim component of the trip? A tantalising photo exists of Paddy Hartnett burning off grass at Lake Will, just off the logical route from Commonwealth Creek to Waldheim along the line of present Overland Track. The author of the semi-fictional Hartnett tour may well have climbed the Razorback on one of Hartnett’s real expeditions— yet in his diaries Gustav Weindorfer never mentioned a Hartnett party arriving at Waldheim from Commonwealth Creek via the Razorback Track.[19]

Leaving aside the matter of whether Hartnett ever brought a party to Waldheim via Razorback, there is evidence in the fictional account to suggest that the author either did in fact make a second trip to Waldheim or was very well informed about changes to that establishment. In her fictional account she mentioned seeing white pegs while rounding the western side of Cradle Mountain. These were possibly placed there by Weindorfer in April 1922 when he was engaged to mark or cut a pack-track from Waldheim to the Barn Bluff mines.[20] The writer mentioned a new woodshed and a ‘tent room’ at Waldheim. These were built 1923–24.[21] Weindorfer’s dog Flock was still alive at the time of the fictional visit—she died on 4 January 1927. Weindorfer was absent from Waldheim from 2 July to 13 November 1926, so he could not have met the timeline suggested by Elizabeth Gregson’s widowhood and removal from Gisborne’s Hut.[22] Puzzlingly, Weindorfer’s diaries contain no reference to Vera Scott, Lydia Morrison or the Joscelynes putting in another appearance at Waldheim after 1922. However, the Joscelynes were friends of Weindorfer whom he visited in Launceston in 1923 and 1926, and it is possible that the anonymous author (particularly if it was Vera Scott, who lived next door to the Joscelynes) was included in these visits and used these to update her knowledge of Waldheim.[23]

Most of ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’ was written in character by Claudia Crane, who married at the story’s end. This time it appears to be her cousin Mona Moore’s turn, although the only names used in the later account are ‘Paddy’ and ‘Percy Lane’. Not even ‘Mine Host’ of Waldheim is actually named. Percy reappears at the end of the epistle to rescue the hospitalised Mona, who has been recalling her trip with Hartnett in the great outdoors as an antidote to the walls of the institution. Since writing a letter for the Waldheim mailbag, Mona has developed a staccato-style of writing with a fondness for the exclamation mark, as if to emphasise her girlish high spirits..

The account

My dear memory Pictures; How I have loved them and lingered over them in these long weeks of imprisonment! How often as I lay here the hospital walls have faded away and great trees have tossed their heads far above me. Once again I and my trusty comrades have tramped ankle-deep in the fragrant lemon thyme [sic], or scrambled happily among the giant boulders on the top of the world. Those long yet all too short days of happy comrade-ship; [sic] the unexpected meeting with our old friend Percy — the glad gathering up of the threads of old time friendship — the intimate talks on every subject under the sun — How I have lived it all over and smiled and sighed over my pictures! Just this once I am going to allow myself to glance at them all again, and then to work!

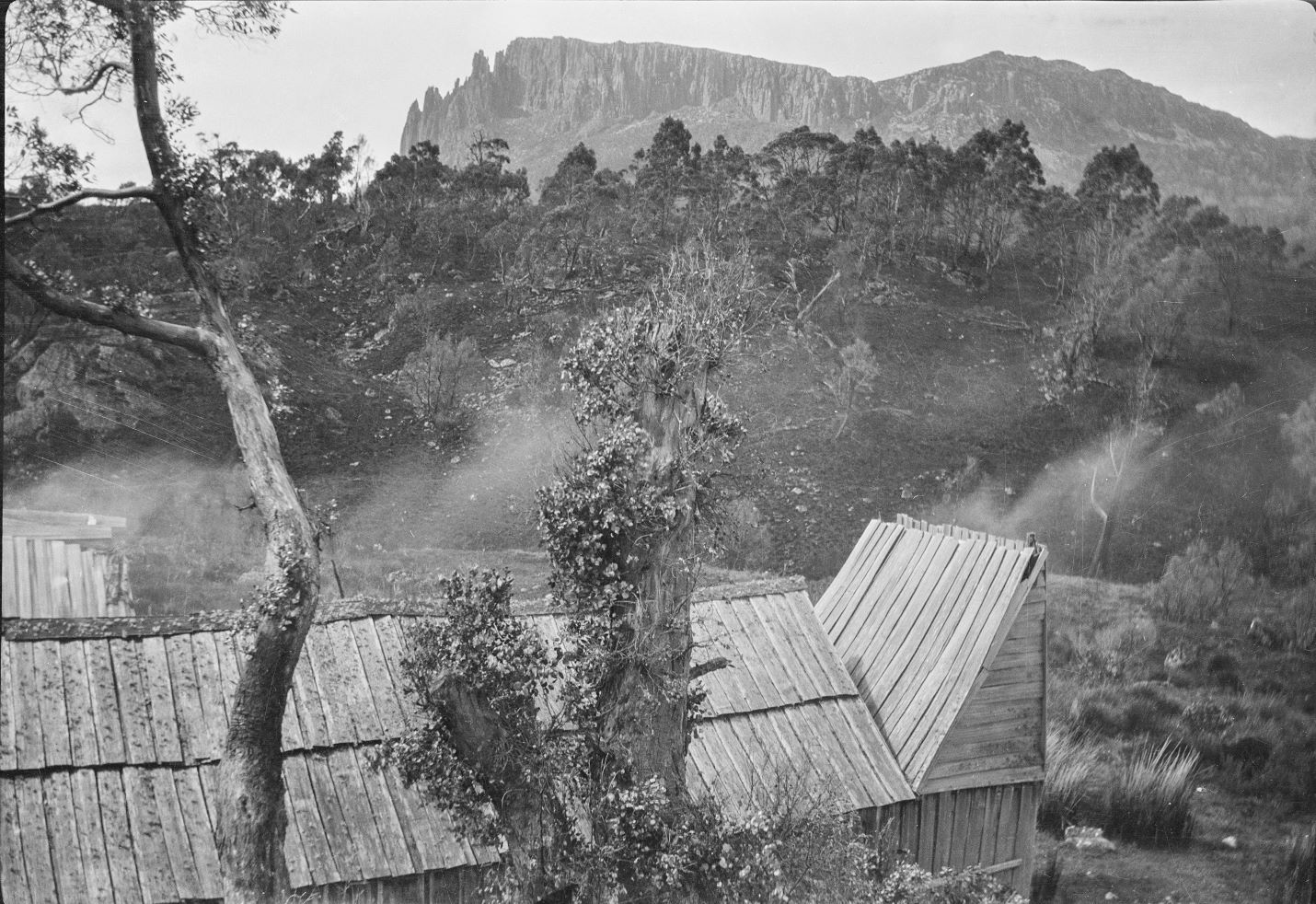

A rolling green slope, hemmed in on all sides by great trees and roofed by the spacious sky. A streamlet purling past two little grey huts sleeping in the drowsy sunshine of a peaceful Sabbath afternoon.[24] A queer ramshackle vehicle toils up the slope and the peace is broken by a little party of Townies. The mistress of the more pretentious hut is a little wiry, shrivelled figure sharp of voice, but ready of smile and disposed to be friendly.[25] She soon has the feminine portion of the party ensconced on her doorstep listening to the finest entertainment she can offer — her gramophone. The entertainment is shared with dogs of all shapes and sizes, but alike in one respect, they are all the proud owners of a coat of thickly matted hair and buzzies. Troops of kittens tumble round but at the slightest movement in their direction they disappear under the house with the unanimity of well-trained soldiers.

As evening approaches the upper hut buzzes with life —the Townies are busily engaged settling in for the night. The wooden chimney proves to be well furnished with holes which admit the evening breezes, the said breezes being frolicsome blow clouds of smoke into the eyes of two busily making toast on forked sticks. The little breezes laugh to see a handkerchief cautiously removed to allow of lightning inspection of the toast and then as quickly replaced over aching streaming eyes. There were no regrets when that fire was allowed to die out.

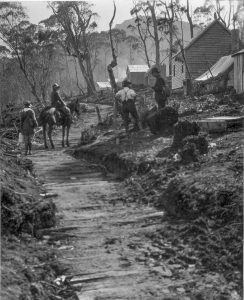

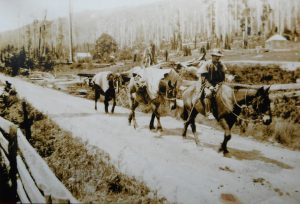

Early morning sweet and fresh! Goodbye! Cavalcade sets forth led by the laden pack horses. Most inexperienced horse-women jogging gently along the beautiful winding path, filled with the deep quiet content of anticipation. The Forth gleams far below — now hiding — now shyly showing its beauty — the glint of the sun bringing out the warm tints of the mineral charged stones paving the clear stream. Presently the horse-women are footwomen by turns with a lame horse limping pain-fully [sic] behind. The pack horses far ahead — hot sunshine streaming down — Footsteps lagging a little.

****

Cool running water — Great trees offering its [sic] services as bridge — at long last the sight of a fire crackling away in the centre of the road! Pack horses minus their loads! Billy boiling! Glorious sense of restfulness pervading every inch of tired limbs stretched out on the cool grassy road. Tea! Lots of it, deliciously hot and wet! A chop, minus salt! A little bag of potatoes doing duty as a table! Our cutlery, a stick and occasional use of a penknife. But no more delightful meal was ever served. More delicious rest on the gently sloping road-side, [sic] now the useful bag of potatoes acting as a pillow. Hands clasped under head (but removed at intervals for vicious swoops at the myriads of droning blowflies floating round.) Eyes gazing dreamily into the smiling blue sky, or lazily following the movements of a tiny fluffy bird hopping and chirping in the feathery grey-green of the young wattles.

****

On once more through beautiful fens and foliage over a narrowing track, the Forth, friendly as ever, still keeping us company. At length, a steep track zigzagging up the hillside, the towers of Mt Oakleigh keeping guard above.[26]

Horseback becoming dangerous, we stiffly dismount and, seated on the rocks of the pathway, gaze with huge respect at the great towers above little thinking that before many hours have passed we will be enthroned thereon, peeping over the edge at our present lowly seat.

Through the Valley of Eden, across the flower-decked plains and, bathed in the lovely evening lights, we have our first glimpse of the circle of guardian mountains which ere long have become such familiar friends.

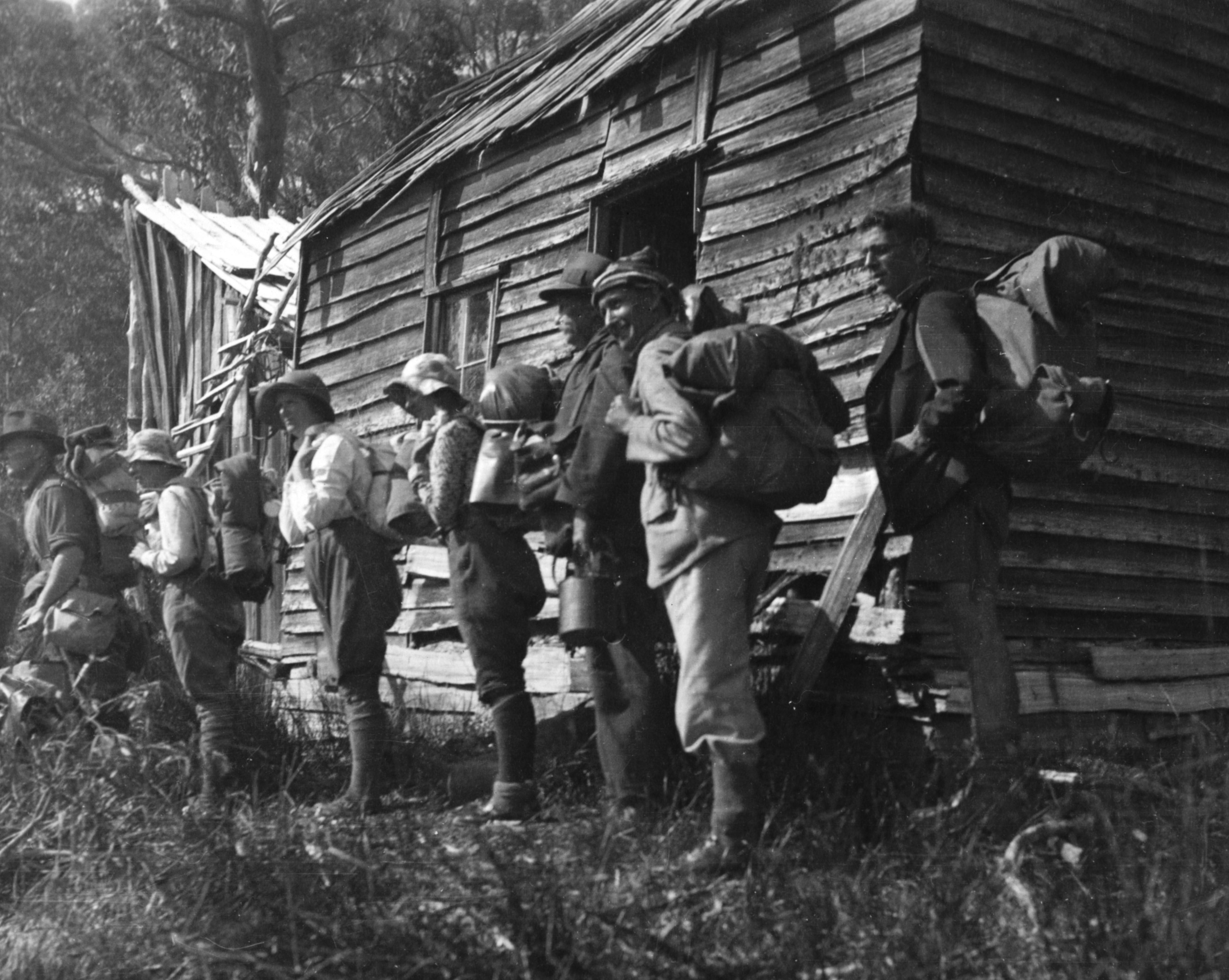

Over the quaintest little bridge, walking on one log and clinging to another — and we are at Pelion Hut — our best loved home! In the next few days what expectant eyes it saw open on the light of a new day! What happy adventures fared forth from its portals and what tired, contented wayfarers returned at eventide!

At first we are a little put to it for lack of utensils, but as the days glide by we are the proud owners of a fine array of jam and fruit tins, which obligingly do duty as jelly molds, saucepans and all manner of things. The boxes in which our groceries were packed are just as obliging, three of them doing duty as table and the remainder as chairs.

Each morning as soon as breakfast is disposed of all are busy as bees preparing for the day’s adventure. On the table appears sundry little screws of paper containing salt, milk, powder, and tea etc; a tin of sugar, a mug of butter; the billy is packed with cups and the whole is soon transferred to the pack on Paddy’s back and off we start on the day’s tramp, cheered by the willing service of our old friend ‘billy’ and his busy little cousin ‘fizz’. When darkness falls, tired, sometimes wet, but happy, our hut sees us once more.

How bright and warm it grows under the combined efforts of huge fire, bicycle lamp, and candles stuck on tin lids. In a very few minutes the billy is boiling, the table fished from under the bunk and put together and the cloth laid (that cloth latterly of serviceable khaki relieved by small irregular splashes of white.)

Our centre piece is a paper serviette and a beautiful bouquet of Waratah [sic], ferny fronds, and graceful foliage, glorifies an empty jam tin given the necessary height of dignity by a pedestal of two tins of fruit. Our sugar basin is strangely like a mustard tin, the salt cellar strongly resembles the lid of that same tin, and they keep company with a most motley array of china, aluminium and enamel ware but we have a real teapot and a net milk jug cover, so what would you?

With what content we sit down to the well earned meal and when the first keen edge of appetite has worn off, push our box seats back so that the bunk supports serve as back rests, and talk and nibble nuts and raisins. Then the table is cleared, dishes washed, occasionally Paddy makes bread or we are visited by a tourist couple from a neighbouring hut, then our boxes are arranged in a cosy circle around the big rugged stone fireplace and a pleasant medley of poems, songs, and chat follows. Sometimes by the combined efforts of the whole party the whole of a song is remembered but usually one or two verses more or less mixed suffice! Even our childhood hymns have their places.

Then appears at the feet of each a cup of steaming coffee. Paddy lifts off the camp oven, ashes are scraped off, the lid is lifted, a chorus of approving voices greets the perfectly baked bread; very soon after that we are in dreamland.

****

Struggling slowly and with many a rest over the flowery plains and up lower slopes of the first mountain Oakleigh — Pushing through shady leafy tangles of vegetation richly illumined by brilliant touches of Waratah in full bloom — On the summit at last gazing our fill from one vantage point — Then being led to another and another until happy hours slip by unnoticed — The leisurely return over the plain in the wanning [sic] light — The magic of the long dreaming rest on the shores of the lakelet faithful mirror of the pearly sunset tints of the sky — Backward glances of Oakleigh now deliciously purple — Until at last the voices of the prudent are heard urging haste and most reluctantly we rise and wend our way homeward.

The swift rush of our descent from Ossa — The excitement of the rapid slides over the smooth snow heightened by the knowledge of great rocks and chasms and unknown depths below — Lowering ourselves cautiously down sheer drops with the friendly aid of the tough pineapple grass.

****

The rush up Thetis striving to race the driving mists to the summit — The biting wind which cuts into us whenever we come into the open — The grand piles of rock which we crawled or scrambled — The moments when we gazed helplessly at some huge heap and turned over for help that was never lacking — Places where the whole party hoisted us up or lowered us down some height — or where we walked up a ladder of human hands and shoulders. The foot reached at last in driving rain — We hastily prepared tea, cold and wet we sat down in one spot and carefully refrained from moving an inch from that partially dried and warm spot.

****

Lake Eyre [sic: Ayr] beautiful in the sunlight in its setting noble parklands. Paddy with an eye to next day’s dinner, leading gun in hand we followed in tip toe — picturesque glimpses of shy wild cattle — Tea interrupted by sudden rain — scuttle for shelter — two girls— lying flat one above the other squeezed beneath a fallen tree trunk — cosy intimate chat, eyes the while noting the lake dipling [sic, rippling?] and colour freshening on tree trunks and foliage under the rain — Contented, tramps round the lake and homeward single file in the gentle rain.

****

A leisurely stroll though plains thickly sprinkled with great daisies — where the plain ends, huge bushes of their smaller sisters greet us.

On we go up long easy slopes of springy green turf beautified by groups of large white orchids. Up here the Forth is young and frolicsome and dances gaily over little falls, turning and turning between beautiful pines that give it quite an alpine touch.

But we have a thought for tomorrow’s dinner despite the beauty surrounding us and keep a wary eye on the joyous flocks of jays noisily chattering overhead[27] — Girls still as mice! Vicious snap of Paddy’s gun! Quick downward fall of mute little body! Reckless plunge of men into the undergrowth! Triumphant return with one more trophy, and so on.

****

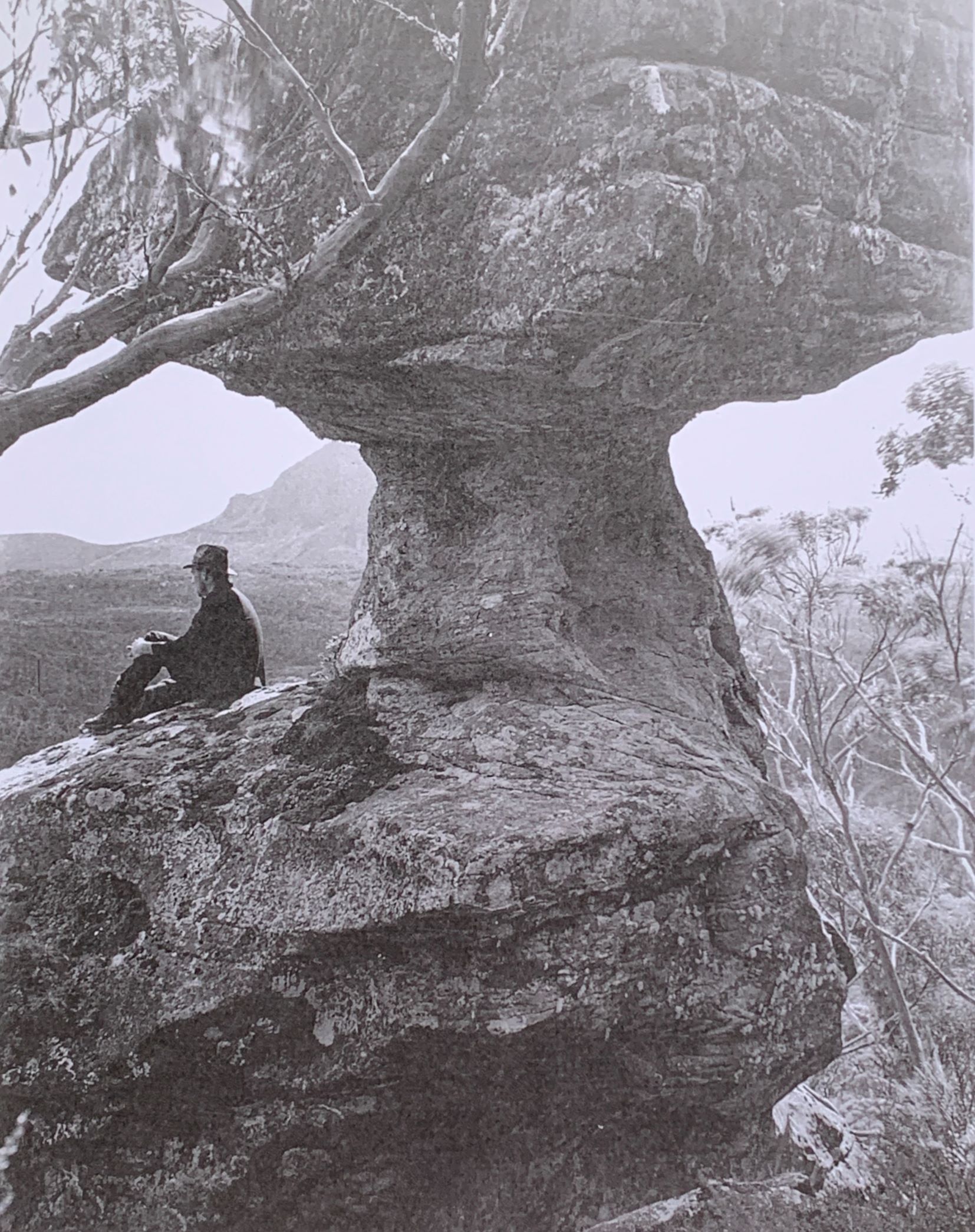

Soon we are gazing on Pelions [sic] giant toad standing on his pedestal on guard, gazing across the tree tops over the hills and far away.[28] We cast wistful glances at Pelion so tantalisingly close, playing hide and seek with the mists; but time and the weather are against us, and we leave him unconquered.

****

One more pleasant picture that day holds — one suggesting Canadian backwoods. A lichen enamelled forest of giant Myrtles [sic] and King Billies, little streamlets making music through tis ferns and mosses — Hidden securely in its heart most picturesque Crusoe huts.[29]

****

Great fire! Billy boiling! Firelight flickering on weary party soon utterly content! Vacuum filled! Thirst quenched! As giants refreshed we rapidly make for home sweet home in the fading light.

****

Our sunshiny day off! A tap awakens us, the door opens, the sunlight streams in! Enter Paddy! Fire alight! Billy boiling! In a trice we are slowly sipping fragrant coffee and nipping biscuits, our eyes feasting on our one picture — a panel of Mount Oakleigh framed in the open doorway. Exit Paddy! Back we lie in luxurious idleness while light-hearted chatter and snatches of song are tossed back and forth through the pine wall.[30]

Leisurely toilet! Leisurely breakfast! Most leisurely household duties! Contented heaping of all culinary responsibilities on capable manly shoulders. Leisurely stroll down to the Forth,[31] very young and pretty between its steep banks. Soon in that secluded spot appears a softly rounded mermaid, splashing joyously in the crystal stream — smiling face and soft brown eyes radiating sheer joy in life. All too soon, alas, she has disappeared, and two commonplace mortals climed [sic] the bank to bask in the sunshine, exchanging low-voiced confidences until a much-uplifted voice summoned them to a wholly unearned, but much appreciated meal.

****

Reluctant farewell to our Pelion Hut, steps retraced with many a backwood [sic] glance! Eyes a fortnight older lingering on remembered scenes. Wolfram! Cautious feet exploring the damp dark mine tunnel![32] Dinner and brief rest at the miners’ huts. On! Over the Forth! Through luxurient foliages! [sic] Through black oozy mud, cautiously skirting the edges of the track at first in the vain endeavour to escape it — then plunging recklessly through it feeling it coldly oozing through the laceholes [sic] of our boots and squelching between our toes!

****

On up the razor back![33] Heats jumping! Breath coming quickly! Loose stones slipping beneath our feet. Ever slower and more slowly in the gathering dark until the pack horses have long disappeared in the gloom above. At long last Paddy and the horses (minus their loads) reappear and the day ends with a mysterious ride in inky darkness. We hear our horses splashing through the water but we cannot see it — we feel branches of trees brushing us as we pass, but these also we cannot see. Perched up on the sky line, we feel like Rebecca on her camel going to meet her lord. All we can see is a black sky far above, pierced by little steel stars. The cool evening air is soft on our faces, and we feel the exquisite luxury of transport on feet other than our own tired ones. Our journey ended, the new hut provokes a smile.[34] The fireplace end is missing and provided easy exit — also access to all and sundry. The floor is thickly strewn from end to end with dry brush etc, but Paddy’s broom of twigs soon sets that to rights. Willing hands have soon unpacked necessaries and gathered our fragrant leafy mattress after a hasty meal on a table which is a most ancient and feeble shell of grey paling which the slightest touch sends askew. An attempt to introduce an extra support shook it so alarmingly that the attempt was abandoned with a fervent prayer that it might outlast our need.

****

Paddy’s voice calling us next morning provoked most dismal groans, but soon we were busily engaged in making preparations for our visit to Cradle of happy memory. Trustfully we leave all but absolute necessities to the mercy of the ‘possum and their friends, and are on the tramp once more.

****

Seated above the wonderful wide sweep of a great cirque, two girls are having shooting lessons, a lovely spray of Blandfordia beside them surveying the performance with wondering eyes.

****

A line of wayfarers pushing rather wearily up seemingly endless slopes thickly clad in a ghostly pale grey thicket of leafless stunted bushes, extraordinarily tough and wiry, its pale skeleton fingers clutching spitefully at our garments as we press through it.

****

A grassy hillside thickly spotted with spikes of pretty pinkish flowers — fly-catchers. Paddy holds a flower in one sunburnt hand — a tiny piece of dry grass in the other. A group of figures kneel round him on the grass, eyes fixed on the flower. Its centre is touched! Down comes the fairy hammer! Little starts! Little exclamations! Peals of laughter! More hammers fall! More starts! More exclamations! More laughter! And so on ad lib.

****

The precious gun and our food are securely hidden in the bushes. Then onward round the white pegs at the base of Cradle, eyes eagerly searching for familiar landmarks. Once round Cradle we allow ourselves one long backward glance at Barn Bluff, softened and beautiful in the deep purple shades of evening, and then on we push. A glad cry announces the first sight of old Waldheim nestling among its pines. We descend the hill a little too far to the left and find ourselves in thick scrub, but on we rush, pushing through clinging branches, jumping, scrambling, anyhow, for we must reach Waldheim before dark actually falls.

Across the plain we break into a quick run — up the hill, round to the kitchen door — the familiar bark of Flock announces us — open comes the door, and we have the hearty surprised greeting of Mine Host.[35] We just have time to note a huge new woodshed facing the kitchen door, when we are swallowed up in the light and warmth. In a very few moments we are round the old table, attending to the needs of the inner man, and making the acquaintance of the other visitors. Then into the cosy old fireplace, chatting and listening to records, old and new, and off to the tent room to long dreamless sleep, buried under piles of grey blankets.

****

Morning! Bright sunshine! Breakfast! Friendly talk! Farewells!

****

On the trail once more! Rest on lovely green fairy mounds starred with tiny daisies. Crater Lake — still — mysterious — deeply, darkly blue — Dove Lake — sparkling dancing in the glorious sunlight. As we climb, many a backward glance is cast at Waldheim nestling in its valley and farewell cooees reach us, softly floating across the distance. The last thing we see as we disappear over the top of Cradle is a friendly white signal waving, and then we set to work in earnest to reach our hidden food.

But the day is far spent when at length it is reached and a silent and empty party sit down to the long deferred meal. But very soon our good friend ‘Billy’ works his magic beneficently as ever, and we laugh once more.

We are seated on the ridge between Cradle and Barn Bluff— those stately old giants gazing serenely over our heads in the soft evening light. One whose face is crimson with sunburn, produces a battered tube of lanoline wrapped in worn brown paper having a goodly share of lanoline upon it. With this paper he proceeds to anoint his burning face. A girl, equally crimson of visage, rummaging among a tiny stock of treasures produces a jar of face cream. Apparently the jolting of the trip has caused the cream to spread itself outside the jar. With this she economically proceeds to anoint her face. Something strange about it invites hasty investigation and with utmost horror she finds she has carefully rubbed tooth-paste [sic] upon her cherished countenance. And those hoary old giants suffer not a wrinkle in their old faces to twitch during the unseemly and ridiculous mirth that follows.

****

Rapidly we push on, but all too soon black darkness is upon us. Closely, blindly we follow in Paddy’s footsteps slipping, stumbling, over bogs, tussocks, stones, seeing not an inch in front of us except where the gleam of water shines warningly. At length rest becoming imperative, we stretch wearing limbs on the cool earth, gazing into the starlit immensity above. Voices break the silence ‘Can you see the duck?’ — minute directions — mystified eyes vainly straining. ‘See the handle of the saucepan — now the sweep of its breast!’ Triumphant laughter! ‘Acres of duck!’ ‘A bonza duck.’ ‘Pooh! It’s a brimming old duck!’ Then mightily refreshed by the sight of that duck we resume our stumbling march! The top of the hill is reached and soon home sweet home with the fresh night blowing through it.

****

Refreshment! Our leafy couches — and Silence.

****

Breakfast in bed and one more lazy sunshiny day of roaming round our hut and the next day we depart! The pack horses have disappeared — absolute necessities are packed and the bulk of the luggage left behind for those most foolish horses on their return up the razor back. This time we have leisure and light to see the beauties bordering the steep track and at the hill’s foot come upon our truant horses returning in charge of the packman. Most gladly the packs are shed and left in the pathway to be picked up.

Through sun-flecked paths the giant bracken bending low and caressing us as we pass we reach the beautiful Forth once more and hot and tired we clamber down its bridge supports to lunch on the cool flat stones in the shade of giant leatherwoods, one mass of beautiful bloom. Here the river is broad and deep and we sit in luxurious coolness watching its smooth flow until the word to march on.

****

Our first hut once more — We now recognise it as a palace with its real glass window and movable table and bunks — wallaby patties made by Paddy — then a visit to our friendly old lady, this time in most wretched and squalid sickness. A nightdress of indescribable hue hangs on her thin form and she is covered by a few soiled and tattered rags; no single sweet or fresh thing to be seen — lack of every little refinement to lighten sickness. On the walls are the only things that might attract attention — every inch of them is covered with magazine cuttings and girls, dogs, horses, all manner of things stare at the poor frail old form. When we left the listless eyes were a little brighter, and in our hearts was a deep pity for all lonely bush women, and especially all sick ones.

****

By dinner time next day our driver and a visiting surveyor had joined us, and we all sat down to our last bush meal — bully beef and onions — with borrowed cutlery added to our already motley collection.

****

One evening the moon looked down and saw the dear little fluffy nurse and the new Doctor [sic] climbing the steps to the ‘Eagles Eyrie’. Now, those steps are steep and the little nurse is plump, so is it any wonder that presently they sat down upon a step instead of climbing it?

When the little nurse got back her breath the moon heard in regretful tones, ‘Our pretty patient leaves to-morrow’. ‘What in the world did you do to her to-day? She looked as if she had got hold of the Elixir of Life.’ [sic] ‘I guess she had’ said the girl softly, ‘And he must have had a dose himself too, judging by the look on his face when he left.’ ‘Well! He’s a lucky chap!’ said the man heartily, ‘Who is he?’ ‘P Lane was on his bag.’ ‘Jerusalem! It must be old Percy! Used to know him at school. His dad lost a lot of money in that Barn Bluff oil show. Met him to-day, and he told me he had struck it lucky — in more ways than one it seems, but he didn’t mention that.’

[1] That is, the old two-chimney Mount Pelion Mines hut that stood below Old Pelion Hut and fell down in 1948.

[2] ET Emmett, ‘Scenic reserve: memorable week’s tour: Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair: Hobart party’s experience’, Mercury, 10 January 1931, p.2.

[3] See ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’.

[4] NS573/1/1/11 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA).

[5] Years are from headstone, Carr Villa Memorial Park, Launceston; plus 1901 British Census as below.

[6] British Census, 1901, Administrative County of London, Civil Parish of Heathorn, p.22 (accessed through Ancestry.com.au).

[7] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of West Launceston, 1922, p.48. See also will of Henry Sidney Scott, in which he made his daughter Vera May Scott his sole executrix and beneficiary, will no.18727, AD960/1/56 (TA).

[8] ‘Thanks’, Examiner, 23 October 1945, p.2.

[9] See will no.43508, AD960/1/94 (TA).

[10] Years are from headstone, Carr Villa Memorial Park, Launceston.

[11] Passenger list for the Orana, October 1891, Series BT27, British National Archives (accessed through Ancestry.com.au).

[12] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of Launceston Central, 1922, p.34.

[13] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of Launceston Central, 1968, p.16.

[14] Descriptive list of immigrants, ss Coptic, arriving in Hobart 27 July 1888,. CB7/12/1/12–13, p.40 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?s=harriet+cumings&searchTarget=library&qu=harriet&qu=cumings, accessed 10 June 2023.

[15] ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 13 May 1893, p.5.

[16] See, for example, ‘Education’, Launceston Examiner, 4 January 1893, p.2; ‘Educational’, Daily Telegraph, 21 January 1896, p.4; ‘Diamond jubilee’, Launceston Examiner, 15 June 1897, p.6.

[17] Married 21 January 1903, registration no.608/1903, at St Paul’s Church, Launceston (TA).

[18] John Gregson’s headstone details are recorded on the Lorinna Cemetery page, Kentish Museum Trust, All known burials in the Kentish Municipality, 2nd edn., 2007. Elizabeth Gregson’s patient admission record for the New Town Charitable Infirmary on 5 August 1926 is HSD274/1/1 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/tas/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fARCHIVES_DIGITISED$002f0$002fARCHIVES_DIG_DIX:HSD274-1-1/one?qu=%22hsd274%2F1%2F1%22, accessed 13 October 2019. Her age was given as 73 years. She never left this institution. Her date of death is also recorded there on 11 June 1927, death record no.1656/1927 (Tasmanian Pioneers Index).

[19] In the Weindorfer diaries the only instance of a party arriving at Waldheim from Commonwealth Creek/Lake McRae is Fred and Ida Smithies on 18 April 1927. They went around the eastern side of Cradle via Lake Rodway, but returned to Commonwealth Creek/Lake McRae via the western side of Cradle on 20 April 1927.

[20] Gustav Weindorfer diary, April 1922, NS234/27/1/8 (TA).

[21] The new woodshed was completed 7 August 1923, the tent room was finished 2 December 1924, Gustav Weindorfer diary (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, afterwards QVMAG).

[22] Gustav Weindorfer diary (QVMAG).

[23] Gustav Weindorfer diary 9 May 1923 and 13 October 1926 (QVMAG).

[24] The author describes travelling south on Patons Road towards the Wolfram Mine on the upper Forth River. The two huts were Gisborne’s Hut, owned by Hobart schoolteacher, orchardist, journalist and political commentator Frederic (FAW) Gisborne, and a hut nearby which was built by Mount Pelion Mines. The Gregsons appear to have occupied the former until the mining hut became available in 1921.

[25] The woman described is Elizabeth Gregson. For the full story of John and Elizabeth Gregson, see Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.100–105.

[26] The author describes the Zigzag Track, the pack track between the Wolfram Mine and the Pelion huts.

[27] ‘Jays’ or ‘black jays’ are currawongs.

[28] Toad Rock, under Mount Pelion East.

[29] A reference to the Crusoe Hut in Cataract Gorge, Launceston, a rustic hut established on the main walkway in 1893 as a reference to Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe, about a castaway marooned on an island off the coast of Venezuela.

[30] The larger hut at Pelion Plain, the two-chimney workers’ hut, was built of eucalypt. ‘Pine wall’ confirms that the hut the author slept in was the mine manager’s hut, now known as Old Pelion Hut.

[31] That is, Douglas Creek.

[32] The main adit of the Wolfram Mine, aka the Mount Oakleigh Wolfram Mine. Wolfram (tungsten) had been needed for munitions during World War One but after the war ended the price of tungsten dropped and the mine was abandoned.

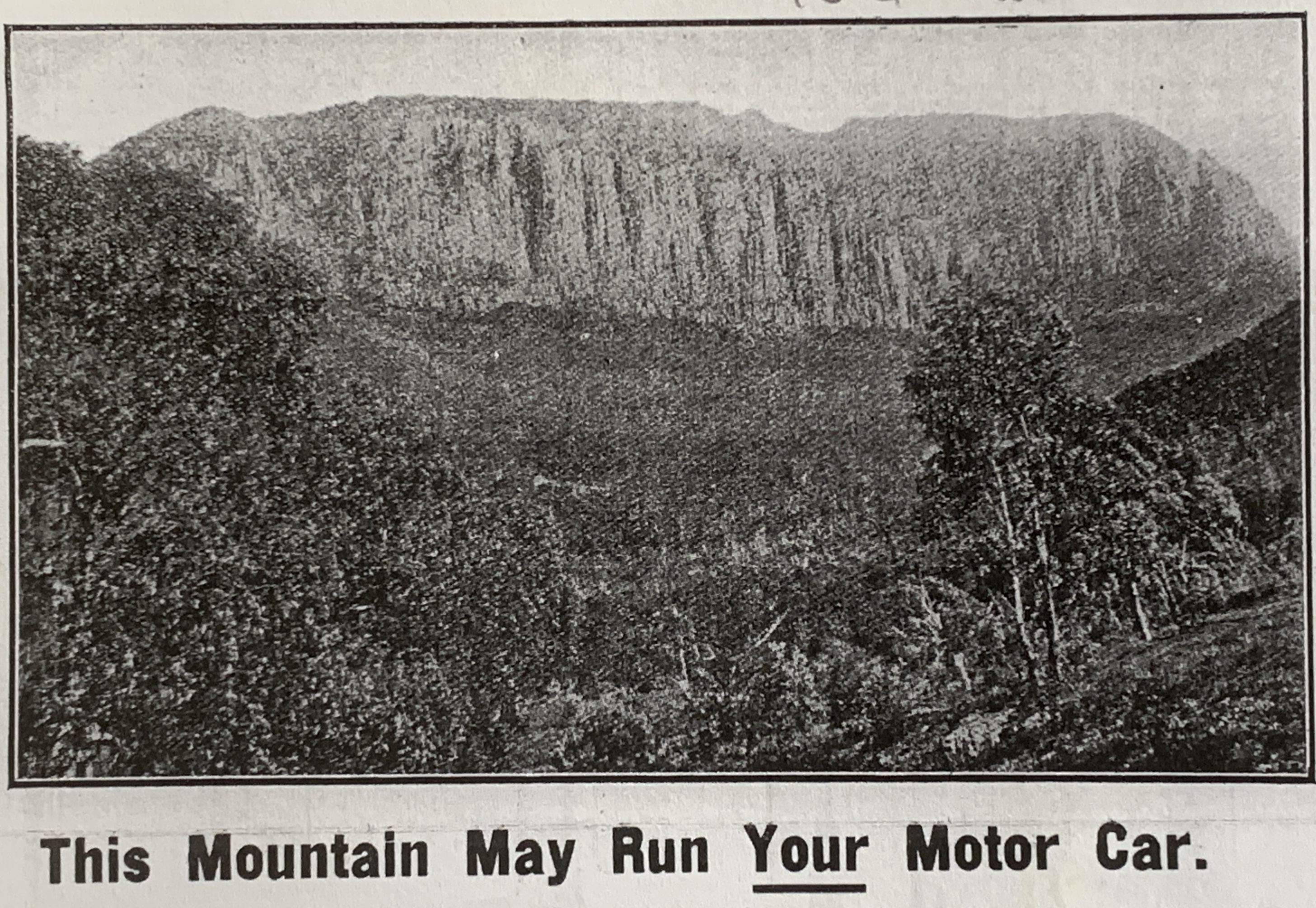

[33] The notoriously steep Razorback Track between the Forth River and the Barn Bluff Copper Mine.

[34] Probably one of the huts at the abandoned Barn Bluff Copper Mine at Commonwealth Creek.

[35] Gustav Weindorfer, proprietor of Waldheim Chalet 1912–32.