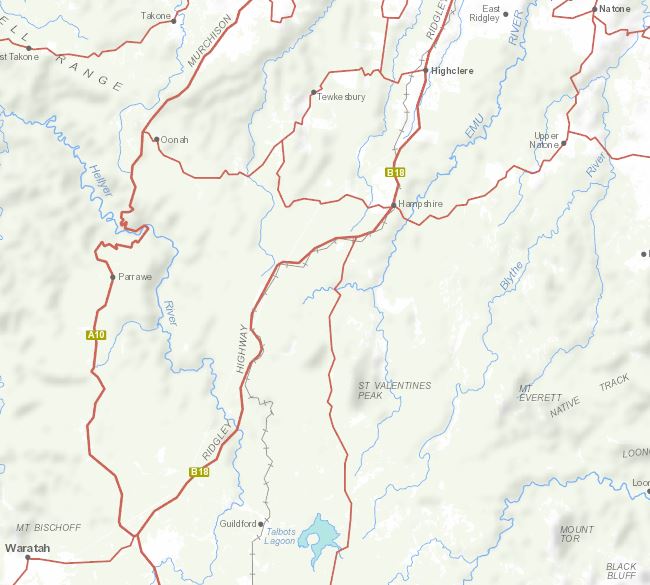

The collection of farms known as Narrawa in north-western Tasmania produced some tough old buggers. The small community west of Wilmot was home to the Carters, Vernhams, Williamses, Bramichs, Lehmans and others, bush farmers resigned to grubbing out, burning and stump jacking their way to cleared pasture. Crops like potatoes were planted in the ashes of the burnt trees as the beginning of farming operations.

After the harvest came the hunt. This was a chance to earn enough money to keep self and family for the rest of the year. Each hunter had his own territory somewhere in the north-western highlands.

Harry ‘Poke’ Vernham/Vernon/Varnham (c1885–c1954)[1]

By the age of 20 Narrawa farmer Charles Henry Vernham already knew his way around Cradle Mountain, being conscripted in the search for hunter Bert Hanson who had gone missing near there in a winter fog.[2] Harry excited more legends than probably any other bushman in his neck of the woods. He was a small man who, paradoxically, wore sandshoes (sneakers) in the bush. Harry was ‘square as a brick’ but so tough ‘you could drive nails into him and you wouldn’t hurt him’.[3] Two stories bear out his toughness. In the snaring season of 1906 Harry cut his knee with an axe in the snow at Henrietta south of Wynyard. He covered the wound with salt and bandaged it with a green wallaby skin, telling his hunting partner ‘You’ll have to do all the snaring. I’ll peg out the skins and do all the cooking’.[4] Eventually Harry presented himself to a doctor, who told him that he was just in time to prevent the onset of gangrene.[5] Harry was then admitted to the Devon Cottage Hospital at Latrobe.[6] Hearing of her son’s accident, Harry’s mother walked about 30 km from Wilmot to Latrobe to prevent a surgeon amputating his leg. She succeeded, but Harry was left with a stiff leg for the rest of his life.[7]

On another occasion Harry’s nose was virtually detached from his face in a motorcycle accident.[8] A doctor told him, ‘I’d better give you a whiff of something before I stitch it back on’. Harry is said to have replied, ‘I didn’t have a whiff when it come off so I don’t need one putting it back on’.[9]

Hunting exploits

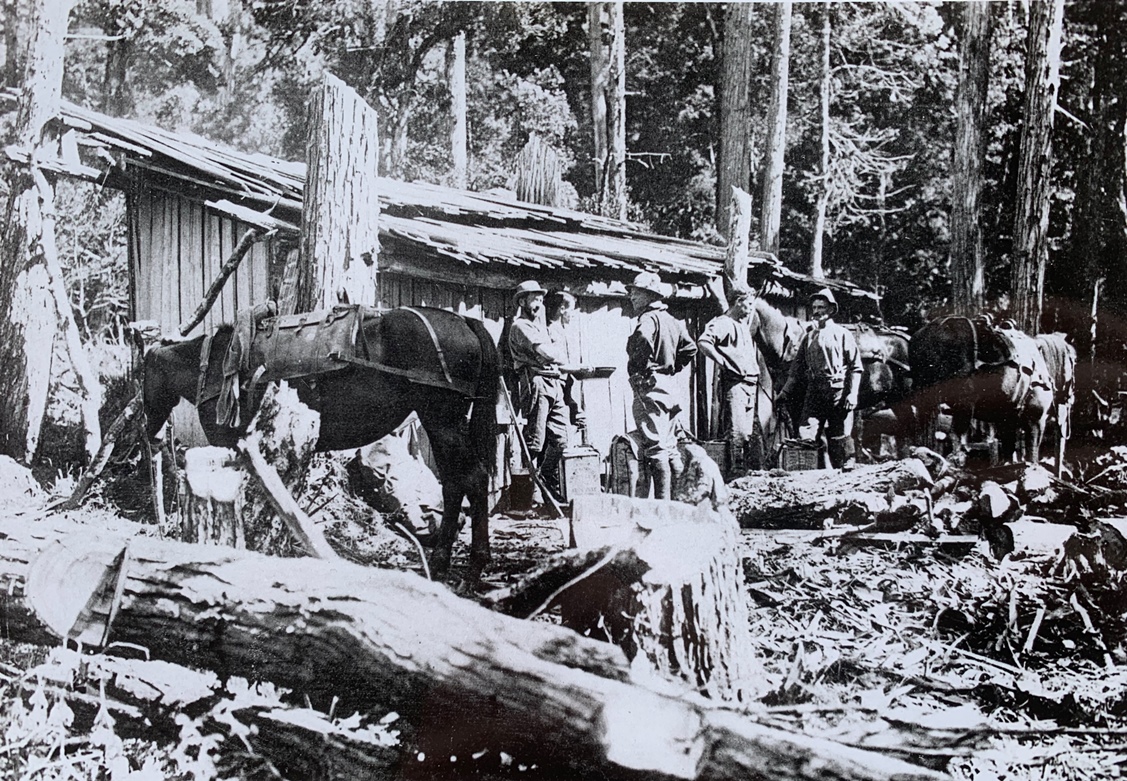

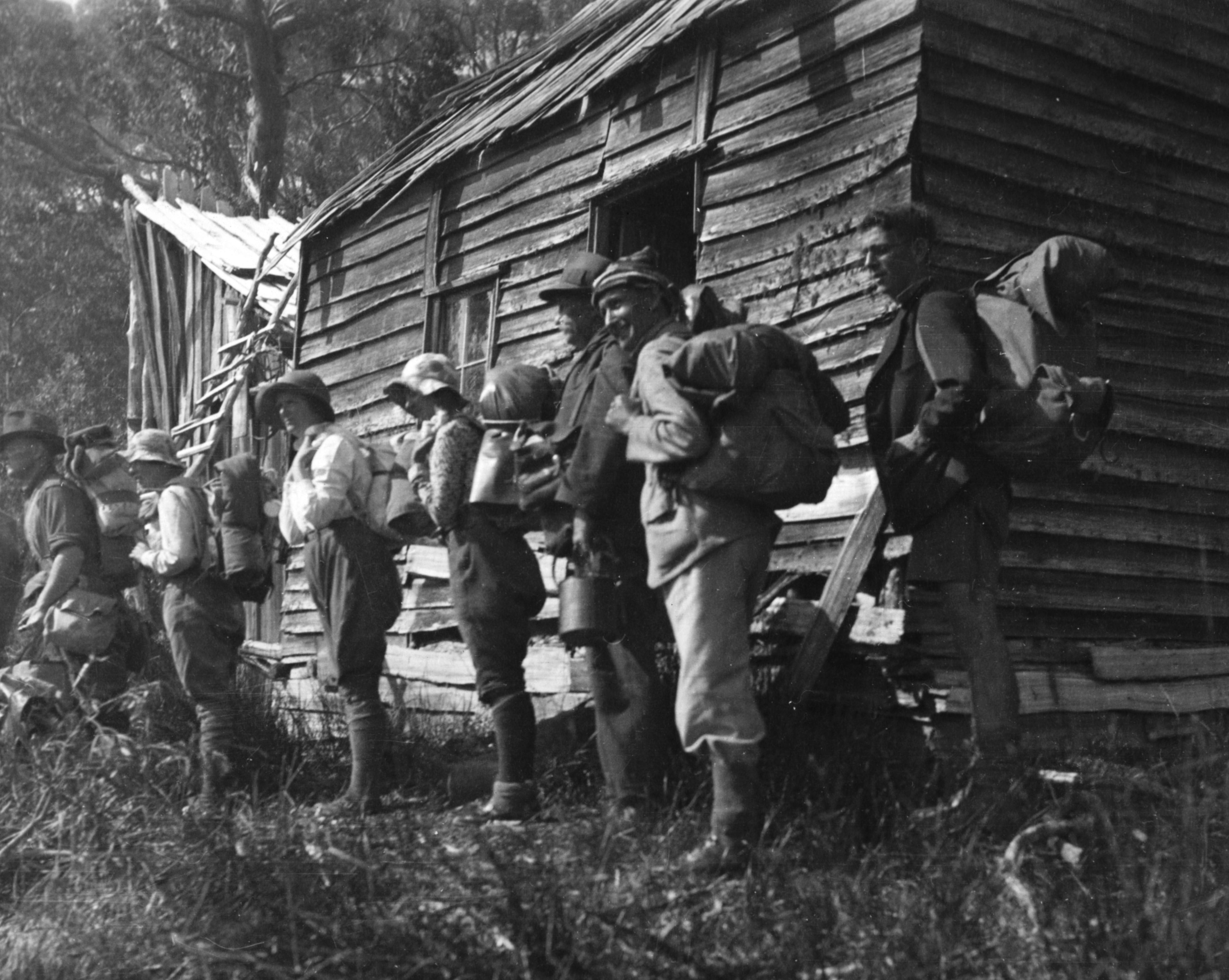

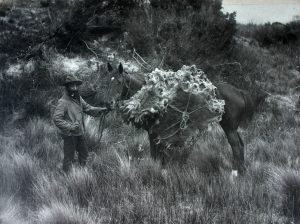

In 1914 Harry married Annie Eliza Carter, from the neighbouring family.[10] They had a boy and three girls over the next four years, but Harry’s nickname Poke suggests that his sex life didn’t end there. At least the hunting seasons were celibate. Harry and his brother George Matthew ‘Native’ Vernham (1889–1966)[11] had a hut on the south-eastern side of Mount Kate and a little log hut near the site of the present-day Cradle Mountain Lodge, the latter being pretty schmick as it was a lock-up affair.[12] Other Harry Vernham hunting companions included Ernest ‘Son’ Bramich (1914) and Harry Leach (1933).[13] Ted Murfet recalled camping with Harry in later years at Middlesex Station, the Twin Creeks Sawmill huts, the hut at Learys Corner, Daisy Dell and Robertson’s on the track into the Vale of Belvoir.[14] They took a dozen balls of hemp for a season and used an old eggbeater to make up their treadle snares on a board about 1.2 m long. Usually they’d need 1000 snares for the season. In their worst season the pair shared £300 and in their best the take was £700—£350 each.[15] By this time Harry had moved beyond the medicinal qualities of a green wallaby skin, developing new home remedies. He treated an ulcer on his leg with a plaster of onion wrapped up in a sock as a bandage and addressed a cold with swigs of Worcestershire sauce.[16]

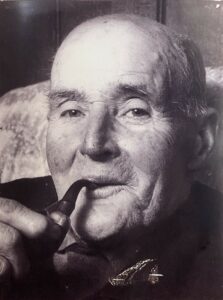

Gordon Murray ‘Bull’ Connell (1889–1972)[17]

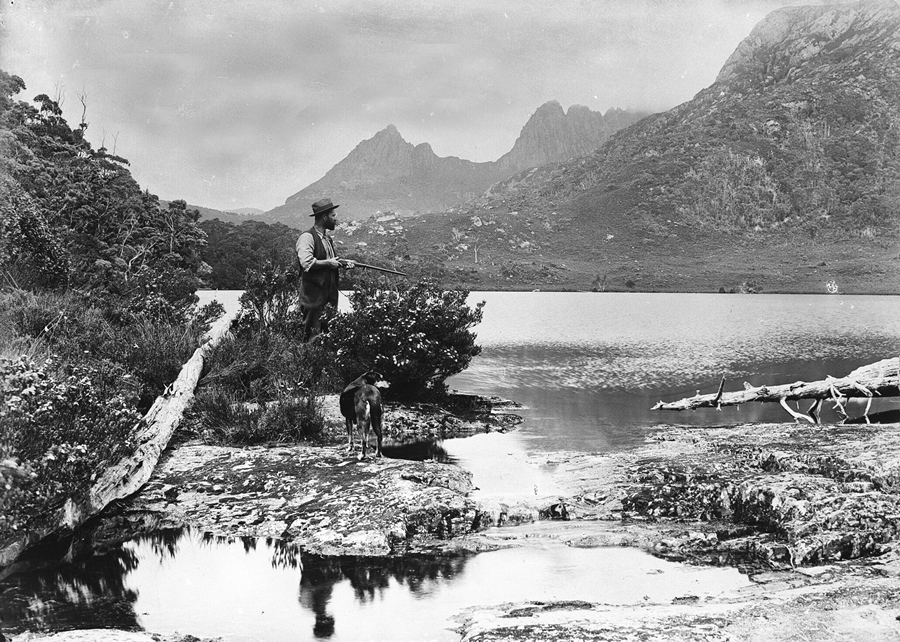

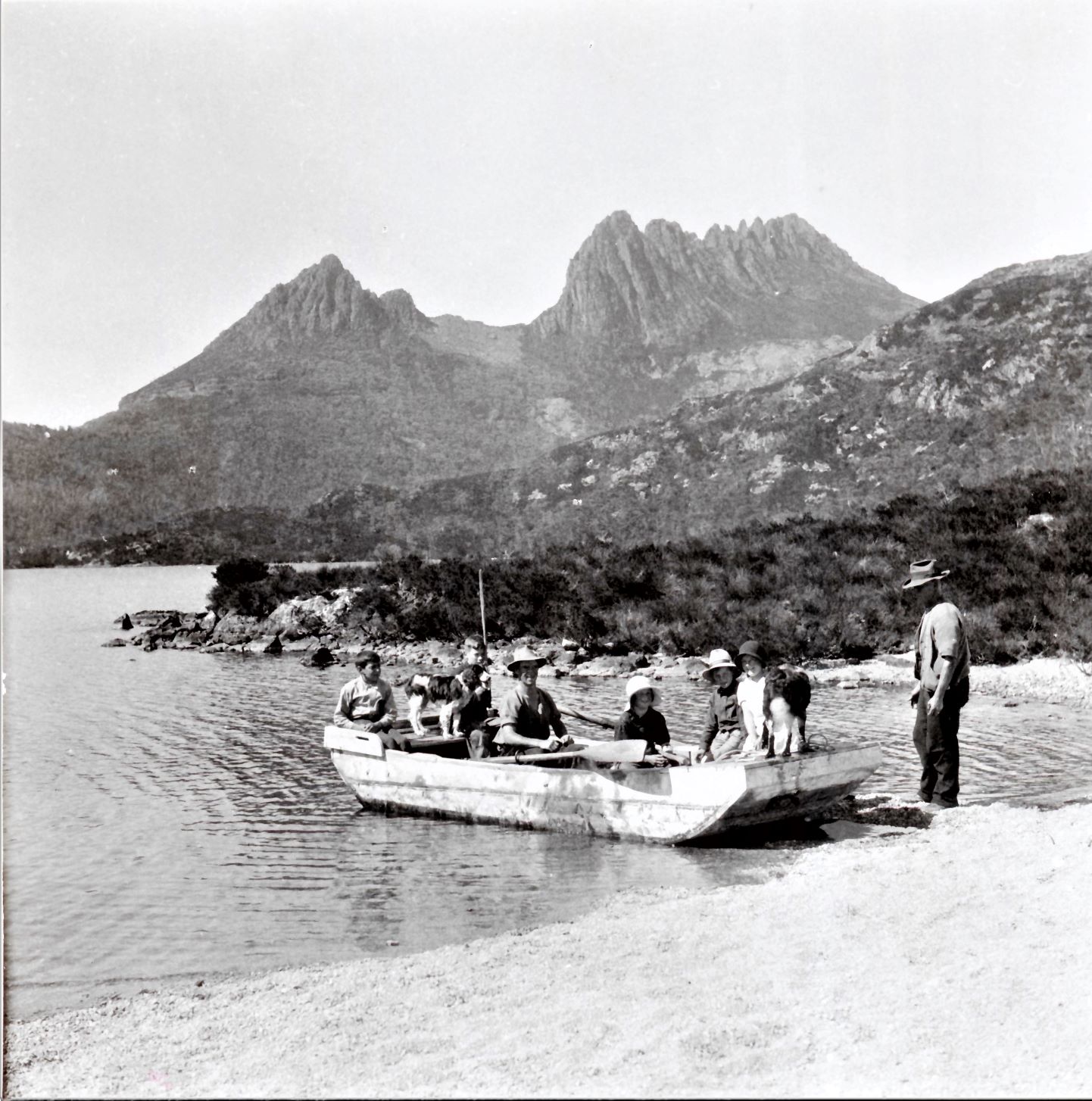

The slow farm development ritual undertaken at Narrawa also applied to the Connell family when they took up the Dunlavin property at the top of Chinamans Hill, Lower Wilmot, in the 1890s. While his older brother Lionel Connell (1884–1960) became a miner, Gordon stayed on the farm.[18] He married Alice Jacklin in 1911, and the couple had at least four children during the next decade.[19] In 1915/16 Lionel Connell and Dick Nichols built a hunting hut in the Little Valley, south of Lake Rodway, and in 1917, when Lionel took a 3-month sabbatical from the Shepherd and Murphy Mine to go hunting, his younger brother Gordon joined him at Cradle.[20] Known as Bull because of his huge shoulders and great physical strength, Gordon hunted with Lionel as far south as the plains between Barn Bluff and the Fury River. He also worked over the so-called Todds Country at the head of the Campbell River.[21] Gordon had a big kangaroo dog called Slocum which would take him to his kills. One day Gordon put his feet up and smoked for 30 minutes before Slocum returned. ‘Where is he then?’, the master prompted, setting the dog off towards Lake Carruthers to a big kangaroo he’d killed. But Slocum wasn’t finished, refusing to budge. ‘Well where is he then?’. Off they went again beyond Lake Carruthers to another big kangaroo carcass.[22]

Gordon hunted with Harry Vernham at Cradle in 1925 and 1926 and in other years around Middlesex and the Vale of Belvoir.[23] They developed a regime of line camps or temporary shelters to get around their extensive snare lines, arriving at base camp only every three days. Gordon recalled icicles forming on Harry’s formidable body hair as he lugged his bag of skins about the snare lines. When Harry stripped off his shirt a huge cloud of steam arose from his singlet, an unusual form of enveloping fog. Wild bulls remaining from Field brothers’ Middlesex grazing operation were an occasional problem for hunters. The worst of these was a territorial bull called Bob because of the ‘bob’ in his tail. Another bull they put a bullet in roared back to life as they approached its apparent corpse. Gordon had a way of cutting a cartridge with a knife to concentrate its potency, but on this occasion it seems to have had the opposite effect.[24]

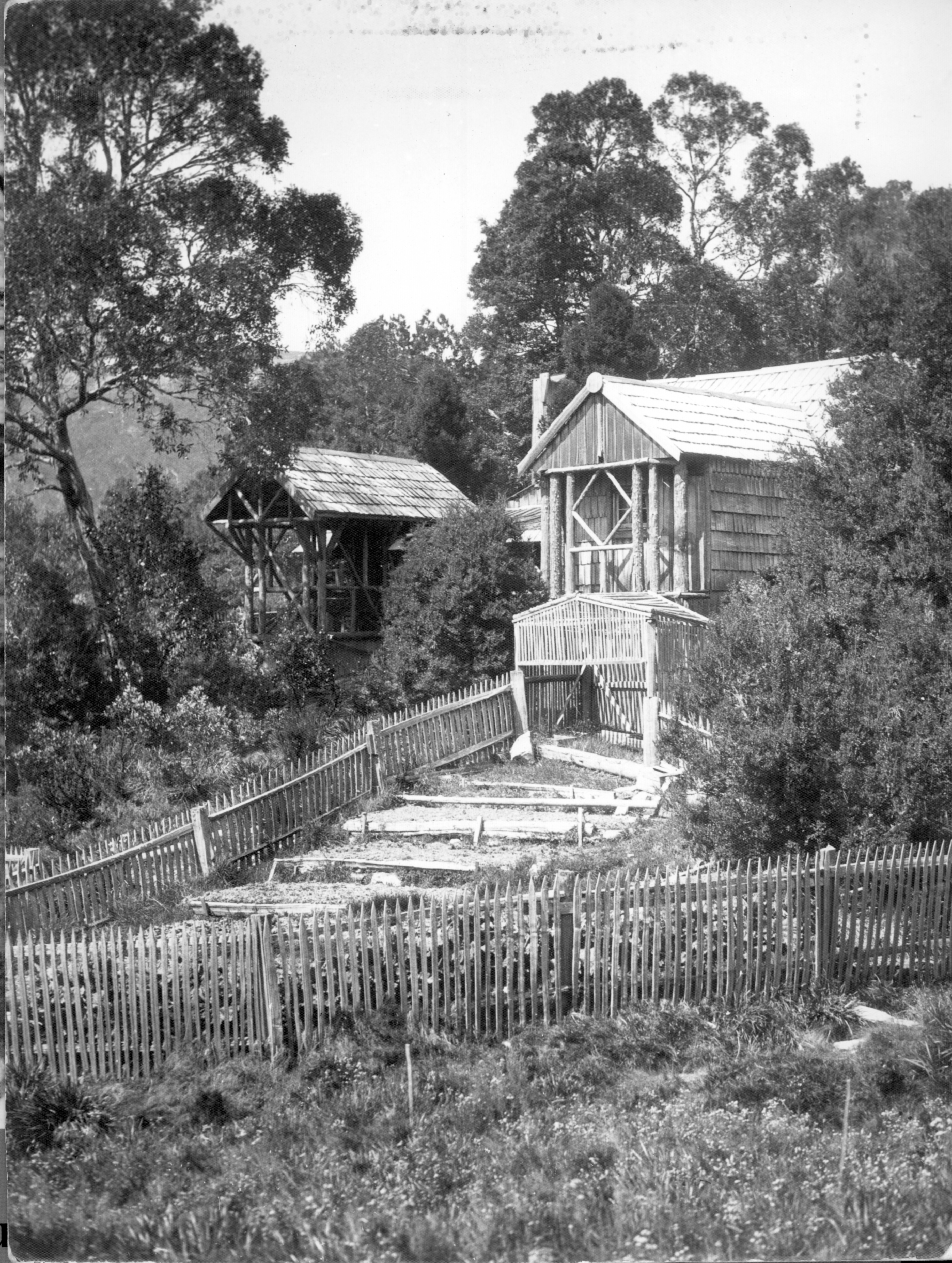

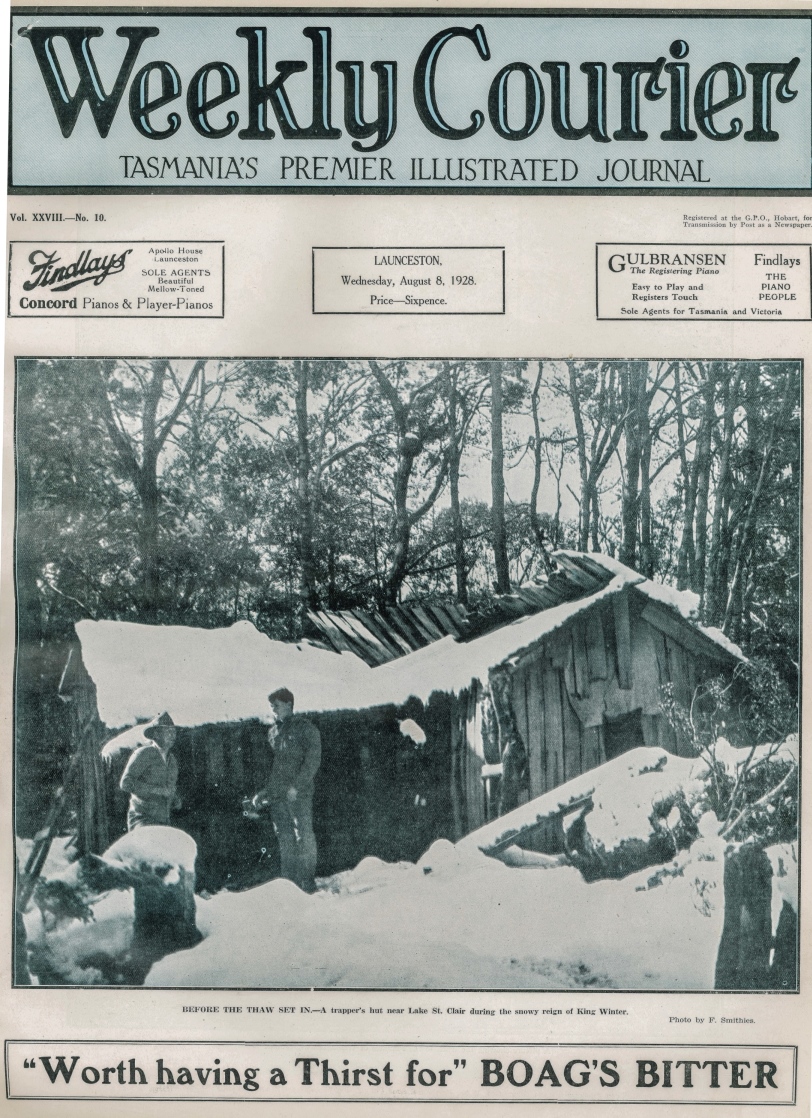

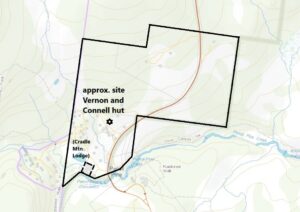

In the 1930s Poke and Bull selected and started to pay off a 99-acre-block at Pencil Pine Creek enclosing the log hut and the old FH Haines sawmill site—land now partly occupied by Cradle Mountain Lodge, the Cradle Mountain shop and rangers’ quarters. Presumably they were either safeguarding their hold on valuable hunting territory or foresaw future tourism development. The pair failed to pay it off, and Lionel and Margaret Connell took over the payments. Lionel’s family were still using the log hut in 1940. Like most hunting huts in the area it had a skin shed chimney, that is, a very large timber chimney in which skins were pegged to dry close to the fire.[25]

The tiger stories

Peter Carter, Harry Vernham’s nephew, claimed that Harry caught thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) in ‘hell-necker’ or ‘hellfire necker’ snares positioned at each end of a hollow log that contained a live wallaby. The ‘hellfire’ appears to have been a heavy-duty neck snare—not terribly surprising, as plenty of tigers were strangled in neck snares. What is surprising is Peter’s claim that his uncle sold skun tigers, that is, tiger carcasses, for £5. Perhaps he meant that he sold tiger skins for £5.[26] Harry Vernham’s name was never entered on the list of payees for the £1 per head government thylacine bounty, although it is possible he claimed bounties through an intermediary. Still, the question needs to be asked why he went to so much trouble to strangle a tiger in a neck snare, when he could just have easily snared it alive by the paw in a foot or treadle device which would have earned him much more money. The story would only make sense if Harry had learned the whereabouts of a tiger or family of tigers and set up the hollow log trap as above, making sure the wallaby was restrained so that it couldn’t spring the snares while making its escape. Prices paid for tigers, dead or alive, varied wildly, so it’s hard to put even an approximate year on Vernham’s tiger sales.[27]

Gordon Connell is another name missing from the government tiger bounty register. He once caught a thylacine dead in the snare—presumably a necker snare which strangled it—but he encountered others in the wild. Bull was said to have found a thylacine lair in one of three rock shelters down in the Fury Gorge while hunting nearby. He shouldn’t have been surprised then when, hunting the button-grass plains above it out of season, he heard an animal yelp. A big kangaroo hopped up the slope, as if disturbed, convincing Gordon and his mate that the police were below them. Then a tiger came up the slope in pursuit of the kangaroo. At regular intervals it stopped and gave three sharp yelps before continuing the chase, as did a second tiger behind it.[28]

What a pity neither Poke nor Bull put pen to paper! We know so little about hunters’ experiences with tigers, but at least these anecdotes give glimpses of what they passed down through family and the hunting community.

[1] Years of birth and death are from Ancestry.com.au, no birth certificate or will was found.

[2] ‘Lost in the snow: a second search party’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 July 1905, p.3.

[3] Peter Carter, interviewed by David Bannear, 16 July 1990, in What’s the land for?: people’s experiences of Tasmania’s Central Plateau region, Central Plateau Oral History Project, Hobart, 1991, vol.3, p.4.

[4] Warren Connell, interviewed 8 September 1997; David Ball, interviewed 25 April 2020.

[5] Warren Connell.

[6] ‘Latrobe’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 29 August 1906, p.2.

[7] Len Fisher, Wilmot: those were the days, pp.46–47

[8] ‘Ulverstone’, Advocate, 26 March 1934, p.6.

[9] David Ball, 24 April 2020. Ted Murfet also told this story to Len Fisher in Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Devonport, 1990, p.82.

[10] Married 15 October 1914, marriage record no.801/1914, registered at Wilmot (TA).

[11] Born to Blackwood Hill, West Tamar labourer William Varnam [sic] and Christina Bowers on 1 February 1889, birth record no.736/1889, registered at Beaconsfield, RGD33/1/68 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=varnham, accessed 3 October 2023; died 7 February 1966, Will no.47656, AD960/1/105 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=vernham, accessed 3 October 2023.

[12] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 12 July 1914 (Pencil Pine Creek), 23 July 1914 (east side Mount Kate), NS234/27/1/4 (TA); 10 July and 10 August 1925 (Pencil Pine Creek) (QVMAG). Es Connell, interviewed by Nic Haygarth on 23 September 1997, confirmed the location of this hut.

[13] Gustav Weindorfer, in his diary, 16 and 18 June 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TA), recorded Harry Vernham and Bramich hunting Cradle Valley and Hounslow Heath with dogs. For Leach see ‘Taking game in close season alleged’, Advocate, 12 September 1933, p.2.

[14] Ted Murfet, interviewed 15 October 1995.

[15] Ted Murfet, interviewed 15 October 1995.

[16] Ted Murfet, in Len Fisher, Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Devonport, 1990, p.81.

[17] Born 29 April 1889 to Michael Connell and Frances Sayer, birth registration no.2639/1889, registered at Port Frederick, RGD33/1/68 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=gordon&qu=murray&qu=connell#, accessed 18 August 2024. The family was living at Torquay (East Devonport).

[18] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.10; Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office Directory, 1919, p.277.

[19] Married 28 March 1911, file no.1384/1911, registered at Gunns Plains (TA).

[20] Gustav Weindorfer diary 29 December 1915 (Lionel Connell and Dick Nichols arrive at Cradle from Moina), NS234/27/1/5 (TA); 1–26 April 1917, NS234/27/1/7 (TA). Weindorfer possibly also referred to Gordon Connell in diary entries in May and June 1917, NS234/27/1/7 (TA).

[21] Todds Country was a name given by snarers to territory hunted by Bill Todd (1855–1926).

[22] Warren Connell.

[23] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 14 July 1925 and 23 March 1926 (QVMAG).

[24] Warren Connell.

[25] RE Smith diary, 29 June 1940, NS234/16/1/40 (TA).

[26] Peter Carter, p.10.

[27] For example,in James 1928 Harrison sold a tiger carcass to Colin MacKenzie in Melbourne for £12 (Harrison’s notebook). In 1930 Wilf Batty sold the carcass of the tiger he killed at Mawbanna for £5 (Wilf Batty; quoted in ‘The $55,000 search to find a Tasmanian tiger’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 24 September 1980, p.41).

[28] Warren Connell.