Mining in a scenic reserve? A fur farm as well? How about damming a protected lake to generate power? Bring it all on. During its first 25 years the Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair National Park was a free-for all.

The national park might have been sparked by a sermon on Cradle Mount but its implementation was more like a meditation on patience. In the 1920s economy reigned over ecology in Tasmania. With the state considered an economic basket case, government had little appetite for funding national parks or for standing in the way of resource exploitation. The Scenery Preservation Board which nominally managed the park had only advisory powers and was, as Gerard Castles suggested, ‘handcuffed’ to this development ethos.[1] Voluntary park administrators attacked their task with a passion. However, their efforts were clouded by conflicts of ideology and pecuniary interest. The first two decades of park management were beset with challenges from the mining, fur and timber industries and the government mantra of hydro-industrialisation. Even the local experts employed to build, maintain and oversee park infrastructure and guide tourists were ‘exploiters’—fur hunters and mineral prospectors. The idea of a road from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair was entertained on the ‘bigger, better and more accessible’ social justice principle that has been used time and time again in Tasmania to justify development of natural assets. What a mess!

Origins of the park

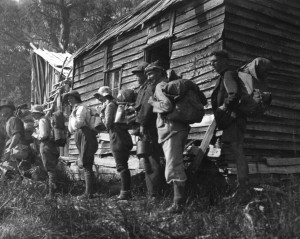

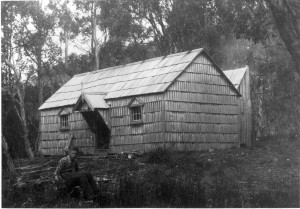

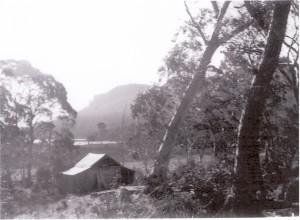

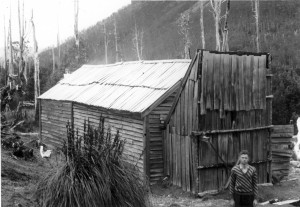

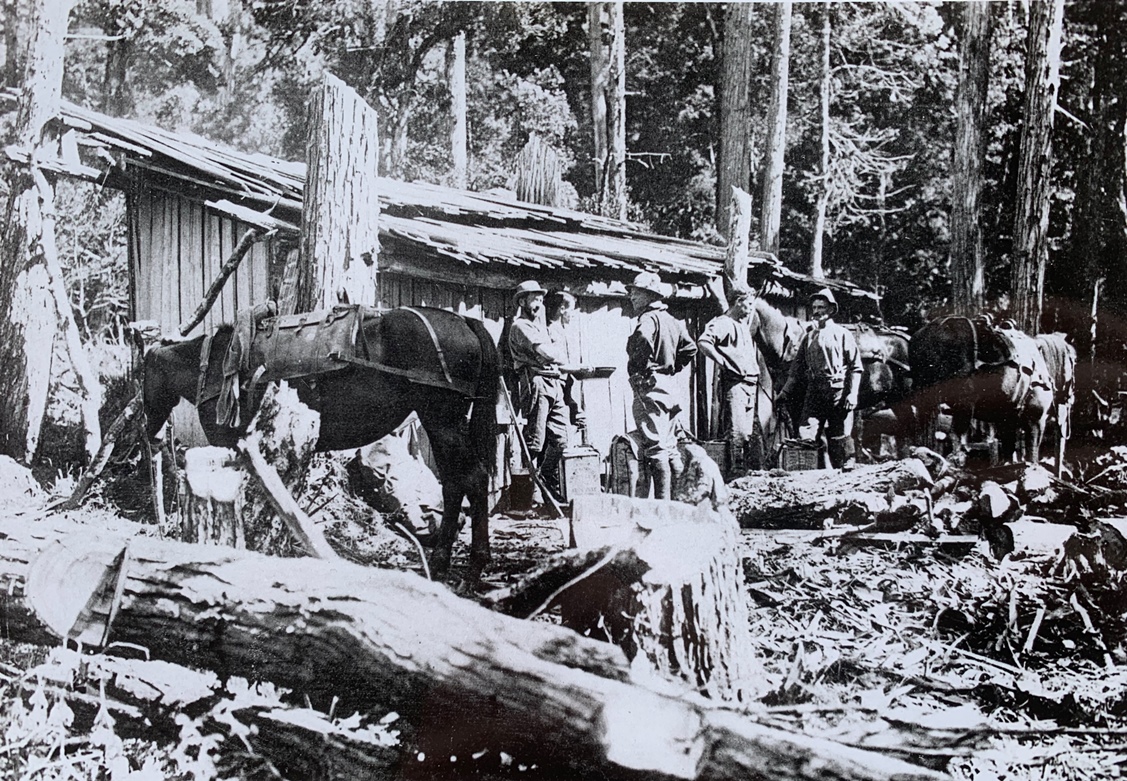

The Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair National Park had three starting points: Cradle Mountain, the Pelion/Du Cane region, and Lake St Clair. At Cradle Valley Gustav and Kate Weindorfer established a tourist resort called Waldhiem in 1912. The story of how they built it and almost no-one came has been told a thousand times. In the Pelion/Du Cane region hunter/prospector Paddy Hartnett had a network of huts, some of which doubled as staging posts for his guided tours as far south as Lake St Clair. Three industrial-size skin drying sheds which stood near Pelion Gap, at Kia Ora Creek and in the Du Cane Gap give some idea of the scale of hunting operations before and after World War One (1914–18). Hartnett’s Du Cane Hut remains today. Lake St Clair had been visited fairly regularly by Europeans for almost a century. It was effectively reserved in 1885 when a half-mile-wide zone around its shores was withdrawn from selection. The Pearce brothers built a government accommodation house, boat house and horse paddock at Cynthia Bay 1894–95 but the buildings were destroyed by fire in 1916.

When Gustav Weindorfer declared famously that ‘this should be a park for the people for all time’, he meant only the Cradle Mountain–Barn Bluff area in which he later operated. Other park proponents, including Director of the Tasmanian Government Tourist and Information Bureau ET Emmett, and bushwalker photographers Fred Smithies, Ray McClinton and HJ King, were familiar with a much greater area. They wanted to include the swathe of land from Dove Lake to Lake St Clair, making an area about six times the size of the Mount Field National Park.

The Scenery Preservation Act (1915), under which the Freycinet Scenic Reserve and National Park (Mount Field National Park) were gazetted in 1916, forbade the lighting of fires, cutting of timber, shooting of guns, removal or killing of birds and native or imported game and damage to scenic or historic features on reserved land. The Act therefore effectively forbade hunting but it did not expressly forbid mining, even though mining always included the lighting of fires and cutting of timber. Parts of the proposed national park area were already logged, grazed, hunted and mined, and to allay fears of these primary industries being locked out of a proclaimed reserve, in 1921 the Act was amended to allow exemptions from the provisions of the original Act.[2]

The Pelion oil field

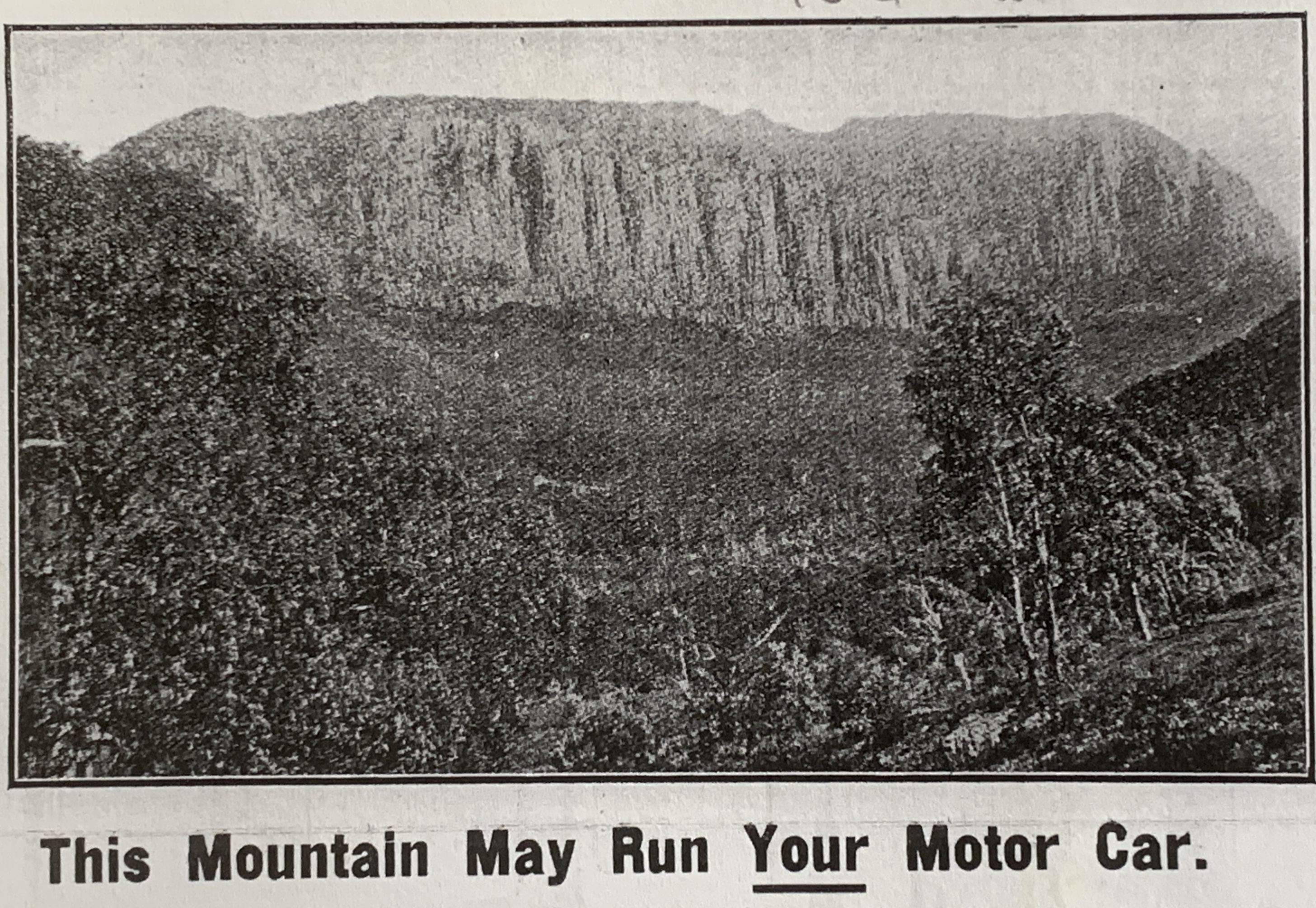

World War One (1914–18) had created anxiety about resource security in Australia and precipitated revolution and civil war in Russia. Outcomes for Tasmania included the search for shale oil reserves and a boom in the Tasmanian fur industry, with brush possum skins helping to make up for the loss of Russian fur reserves. While a lantern lecture campaign promoted the idea of a Cradle Mountain national park in 1921, about 80,000 acres of the land in question was under exploration lease in the search for shale oil (‘inspissated asphalite’). The Adelaide Oil Exploration Company used a Spurling photo to push the idea that Mount Pelion West was a motor oil bonanza. Its proponents assured would-be investors that its lease contained ‘the greatest potential amount of wealth hitherto controlled by any one concern in the British Empire, and, probably, in the whole world, outside the United States of America’. Faith might be able to move mountains, but the government geologist assured them it couldn’t put oil in these mountains. The only lasting impact of oil exploration was the Horse Track south from Waldheim, which was marked to enable pack horses to supply coal/oil operations at Lake Will.

Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

The Cradle Mountain fur farm

The Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair Scenic Reserves were gazetted under the amended Act in 1922 but at first neither was a fauna sanctuary under the Animals and Birds Protection Act (1919). With the surge in hunting it was inevitable that fur farming on the Canadian model was proposed for Tasmania. The Fur Farming Encouragement Act (1924) reserved 30,000 acres at Cradle Mountain for a fur farm, but before local hunters could protest, in 1925 this area was dismissed as unsuitable by two of the scheme’s proponents, Melbourne skin buyers who, extraordinarily, believed that ‘furs grown at a high altitude have not the good texture of those grown on the low lying country’.[3] Nobody seems to have counselled Tasmanian hunters that high country furs were inferior. Working at Lake St Clair in the winter season of 1925, Bert Nichols reportedly made the small fortune of £500, his possum skins fetching 17 shillings 11 pence and his wallaby skins more than 12 shillings each at the Sheffield Skin Sale.[4] This was at a time when the average annual wage for a farm worker was about £110 to £125.[5]

Two subsidiary management boards

Two subsidiary bodies were appointed to advise the Scenery Preservation Board on matters relating to the two adjoining scenic reserves. One, the National Park Board, already helped manage the Mount Field National Park. Chaired by botanist Leonard Rodway, with Tasmanian Museum director Clive Lord as its secretary, it now added the Lake St Clair Scenic Reserve to its purview. The other body, which administered the Cradle Mountain Scenic Reserve, was created from nominated representatives of interested organisations and municipal councils plus several people who had campaigned for the reserve’s creation.[6] Ron Smith (Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary from 1930) and Fred Smithies became standard bearers for the 68,000-acre Cradle Mountain Reserve, but their simultaneous ownership of land at Cradle Valley inevitably led to a conflict-of-interest situation.

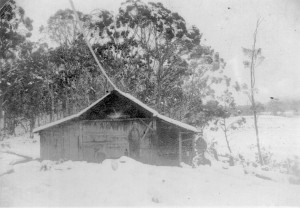

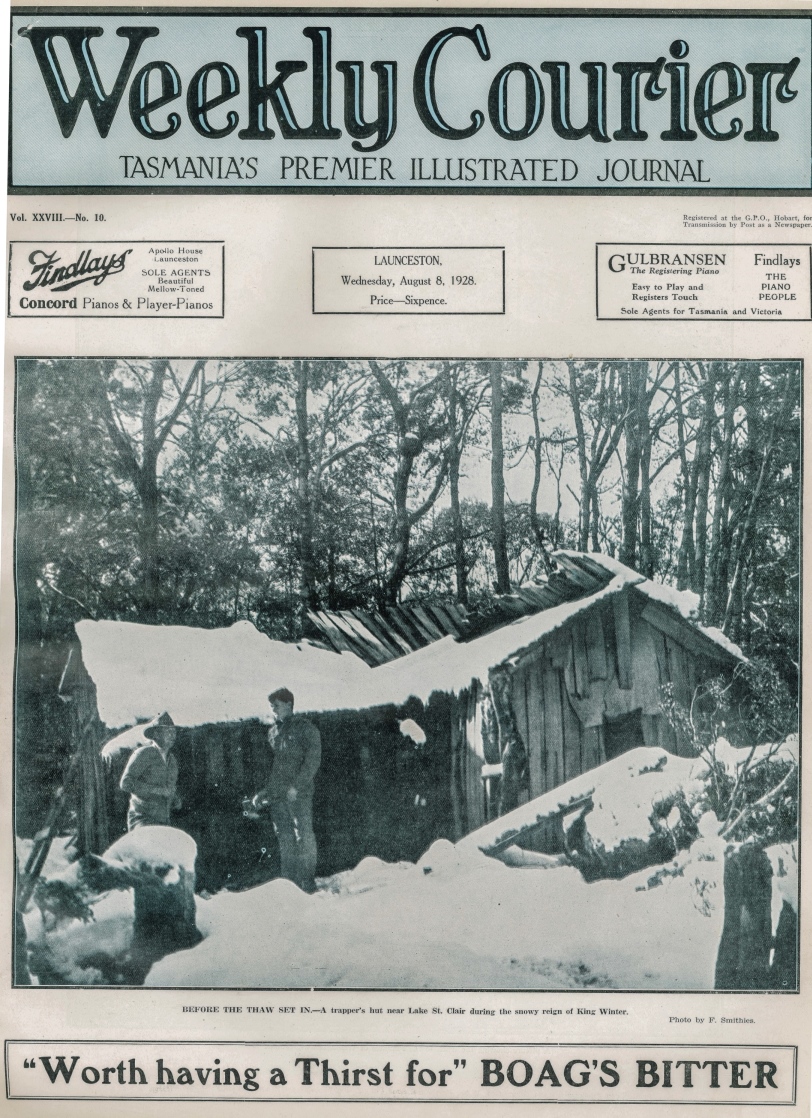

Weekly Courier, 8 August 1928. Courtesy of Libraries Tasmania.

During 1927 the Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair Scenic Reserves were gazetted as fauna sanctuaries.[7] Two months later the hunter/prospector Dick Nichols was nabbed for poaching at a hunting hut in the Cuvier Valley. His brother Bert was probably around somewhere too but escaped detection, and it became clear that they had a network of hunting huts around Lake St Clair and in the Cuvier Valley.[8] Fred Smithies, a member of the CMRB, was used to sleeping among the drying pelts in Bert Nichols’ Marion Creek Hut.[9] In the winter of 1928 he took a lovely photo of it under snow and this poacher’s hut in a fauna sanctuary made the front cover of the Weekly Courier newspaper![10] Nichols later duplicated the hut for the use of Overland Track walkers.

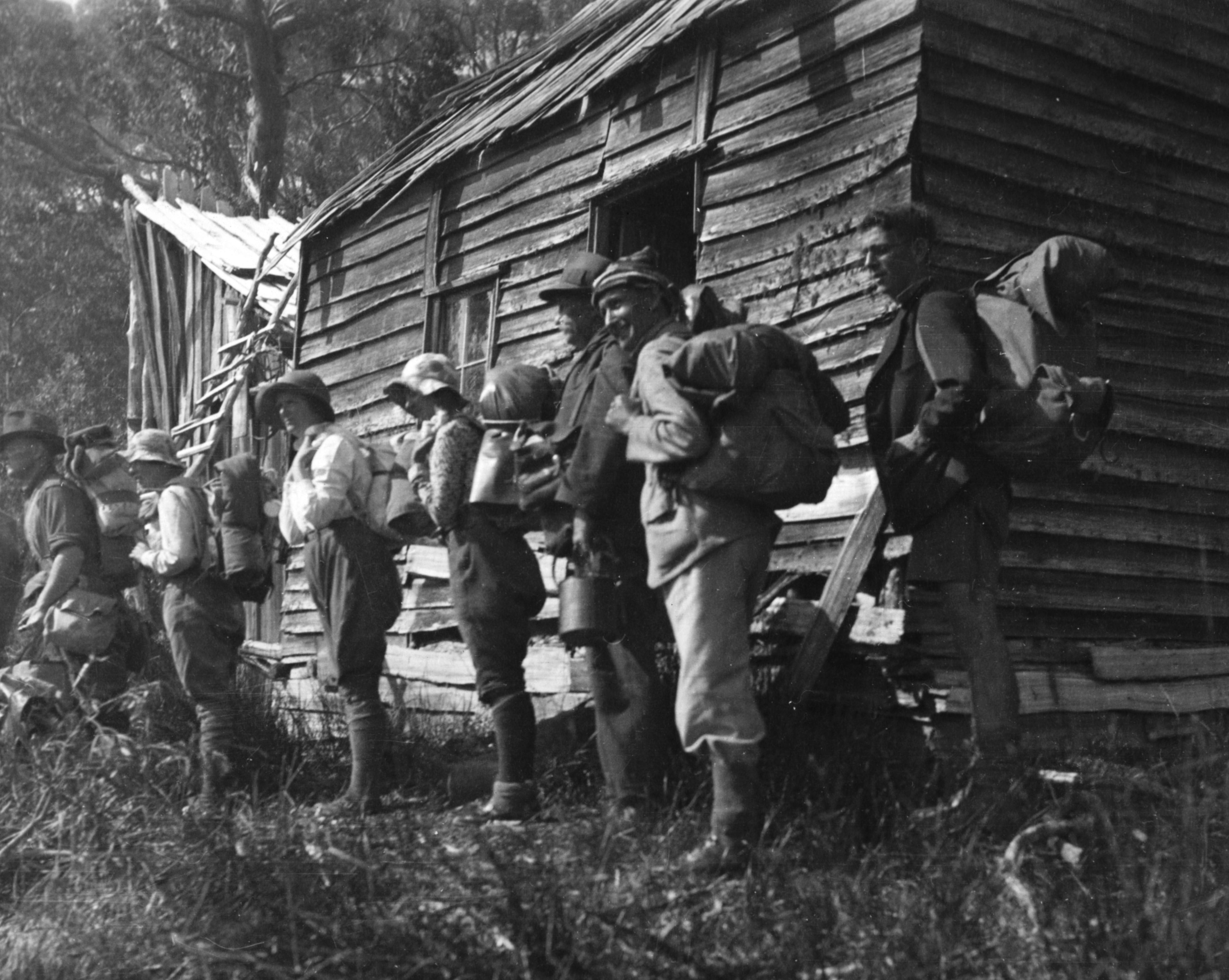

The Overland Track

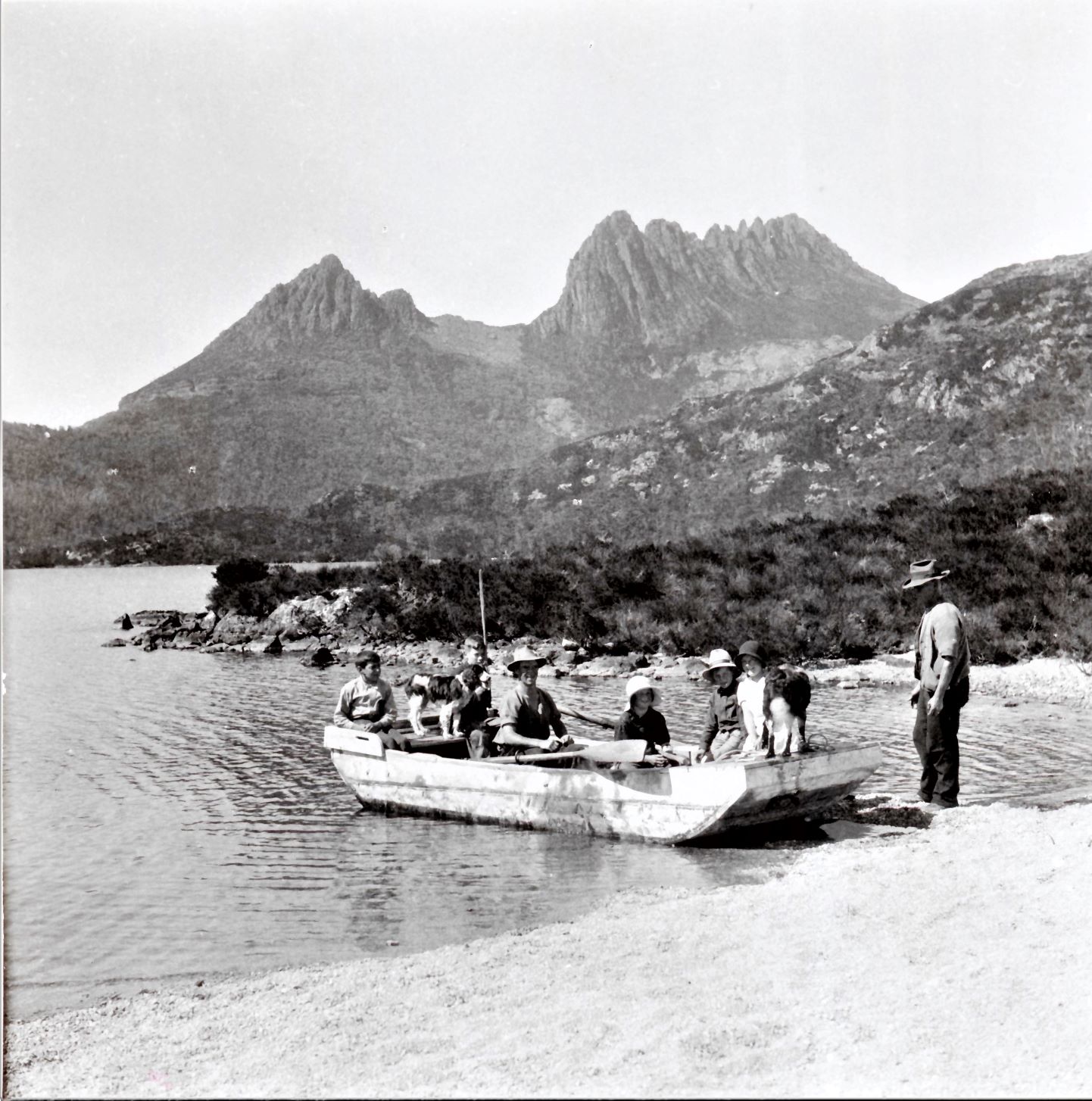

The idea of threading a track through the two reserves to unite them seems to have started with Ron Smith, who in 1928 envisaged an ‘overland track’ connecting Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair, including a motor boat service on the lake.[11] Sections of track that could be linked already existed, including that marked by Weindorfer from Waldheim to Lake Will (the basis of the Horse Track), the Mole Creek Track between Pelion Plain and Pine Forest Moor, and hunters’ tracks from Pelion Plain through to Lake St Clair and the Cuvier Valley. Paddy Hartnett offered to cut the Overland Track for £440, but Bert Nichols did it for only £15.[12] He connected up sections of track and cleared others south of Pelion Plain to form the Overland Track in 1931.[13] Mining, hunting and tourism huts like Old Pelion, Lake Windermere and DuCane were adopted as staging posts along the track.

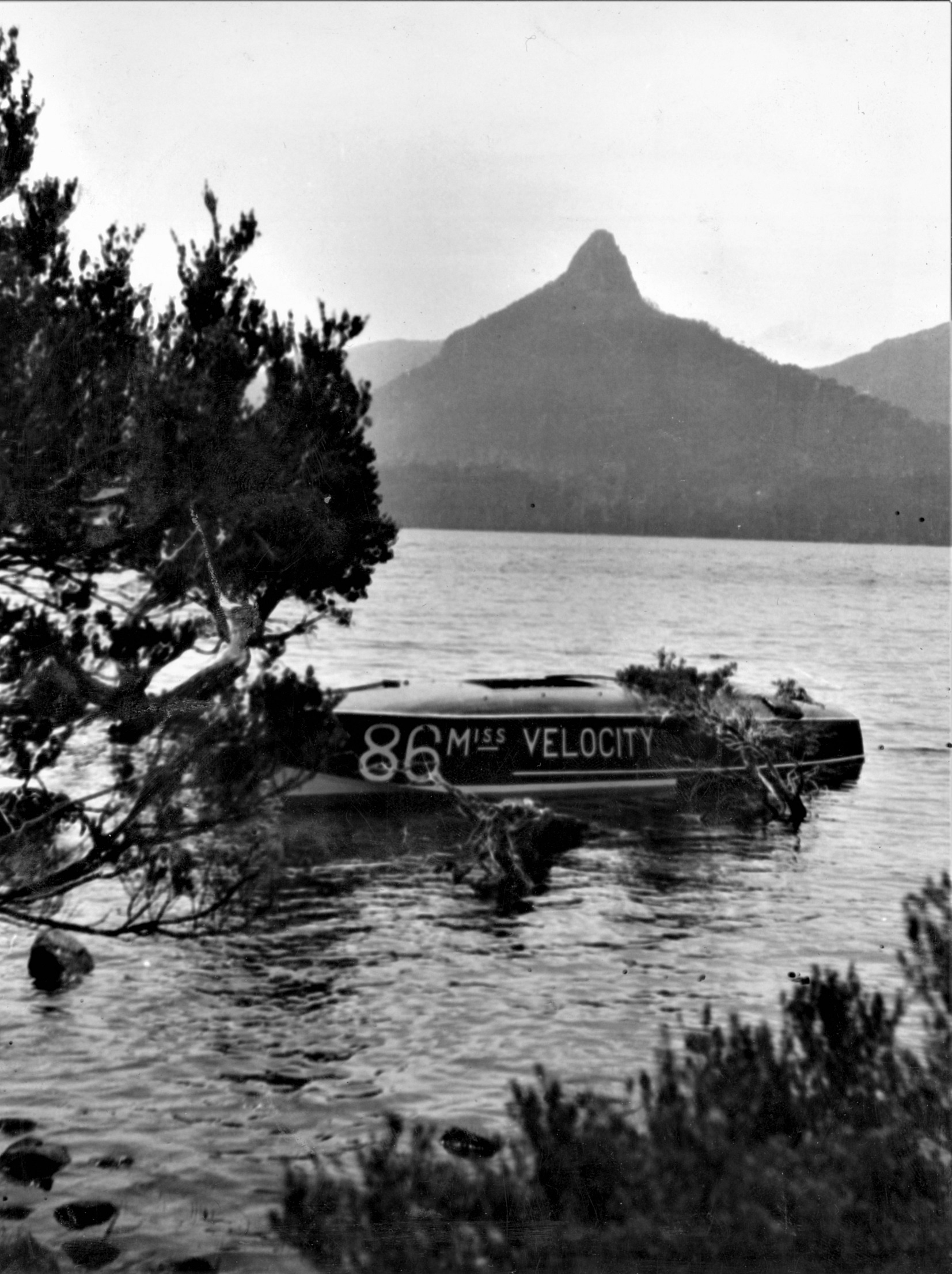

Although the official Overland Track went through the Cuvier Valley, it soon became standard procedure to cross Lake St Clair instead on tourist operator Albert ‘Fergy’ Fergusson’s motorboat. During the Great Depression Miss Velocity was an integral part of Bert Nichols’ guided tours on the Overland Track. Fergy’s tourist camp of sixteen tent-huts with earthen floors and a communal rustic dining room rivalled Weindorfer’s set-up at Cradle Valley.[14] He employed a housekeeper and owned a ‘frightful old bus’ with sawn-off cane kitchen chairs for seats, with which he drove walkers out to the Lyell Highway at Derwent Bridge.[15]

The death and wake of Gustav Weindorfer

Gustav Weindorfer died of cardiac arrest in Cradle Valley in May 1932, apparently in the act of trying to start his Indian motorcycle.[16] His name was already inscribed on his wife Kate’s headstone at Don in anticipation of him joining her there but a group of his friends arranged his interment in front of Waldheim.[17] Ironically, despite his love of the place, for years Weindorfer had been trying to sell and leave Waldheim.[18] Now he was stuck there!

The Austrian secular tradition of remembering departed loved ones was adopted at Weindorfer’s grave after his sister Rosa Moritsch sent a bunch of flowers and four small candles from his native land. These were placed on his grave on New Year’s Day 1933. For several decades Weindorfer’s good friend Ron Smith organised the annual New Year’s Day ceremony. The annual commemoration of Weindorfer’s life has assumed possibly unparalleled longevity among Australian public figures.

The work of the Connells

First Bert Nichols and then Barrington farmers Lionel and Maggie Connell looked after Waldheim before a syndicate of Weindorfer’s Launceston friends (George Perrin, Charlie Monds, Karl Stackhouse and Fred Smithies) bought the chalet from his estate.[19] They asked the Connells to stay on as managers. Lionel Connell had been snaring around Cradle Mountain for two decades and knew the country well. The Connells, with six sons and daughters to help them, set about making Waldheim financially viable by extending the building and improving access to it.

In the late 1930s the Connells had a tourism package for the Northern Reserve that far exceeded that of Gustav Weindorfer, ferrying visitors to and from Waldheim in their car, accommodating visitors, feeding them with produce from the farm at Barrington, guiding them around Cradle Mountain and even guiding them on pack-horse tours on the Overland Track.

Fergy’s other tub: early rangers

Ex-hunter and Overland Track guide Bert Nichols is said to have removed Overland Track markers when they were not needed in order to snare undetected in the fauna sanctuary. Nichols did other infrastructure work and was appointed ranger for two months in 1935. However, when the time came to appoint a permanent ranger the known poacher was not considered for the job.

A Lionel Connell hunting hut built with Dick Nichols still stood south of Lake Rodway as a reminder of the former’s past. Yet Connell was considered fit for a permanent posting as ranger.[20] The Connell family demonstrated great enterprise in their work at Cradle but conflict between Lionel’s roles of privately-employed tourism operator and government-employed ranger at the same location were soon obvious. To compound the issue, Connell managed Waldheim for Smithies and Karl Stackhouse. These men, as members of the CMRB, also effectively employed him as a ranger. CMRB Secretary Smith also had a family tie with the Connells.

The other remarkable early ranger was Fergy who, like Lionel Connell, combined the job with that of tourism operator. His toughest journey was not on the lake but in an upside-down bath. While building the original Pine Valley Hut, the Lake St Clair ranger lugged an iron tub to it about 10 km from Narcissus Landing by balancing it upside down on his shoulders and head, his forehead reputedly having been reinforced to mend a war wound (his World War One record suggests only that he suffered from shell shock and deafness). Stripping off in the heat, his curses echoing inside the bath, he was stark naked when he ran into a party of bushwalkers.

Extension of eastern and western reserve boundaries 1935 and 1939

The extension of fauna sanctuary boundaries to natural features was done with the intention of negating claims by hunters that they weren’t sure where the boundaries were. Tommy McCoy seems to have known. His Lake Ayr Hut was cheekily perched within sight of the reserve boundary. Reactions to it showed the distinction between the old-style conservationists in the park administration and the new ones of the bushwalking community. Cradle Mountain Reserve Board Secretary Ron Smith, a former possum shooter, respectfully left payment of threepence for a candle he removed from McCoy’s camp.[21] Hobart hikers, on the other hand, became conservation activists, puncturing McCoy’s canned food with a geological pick when they found his hut in 1948.[22] McCoy, like fellow snarers Paddy Hartnett, Bert Nichols and Lionel Connell before him, embraced the opportunities offered by tourism, building and repairing Overland Track huts. He was proprietor of Waldheim Chalet when he died in 1952.

Damming Lake St Clair 1937

The Art Deco Pump-house Hotel which juts into southern Lake St Clair, as if walking the plank for its crimes, is a symbol of gradually changing values. In 1922, in a joint lecture about ‘preserving’ the tract of land south from Cradle Mountain, Ray McClinton and Fred Smithies deplored the ‘firestick of the destroyer’ and the ‘ravages of the trapper’ but spruiked the hydro-electric potential of the region’s lakes.[23] Fifteen years later the naivety of this position became apparent when the Hydro-Electric Department dammed the Derwent River as part of the Tarraleah Power Scheme. After assuring the National Park Board that Lake St Clair would be unaffected, it raised the lake’s water level by more than a metre, sinking the golden moraine sand (the Frankland Beaches) and the accompanying islands once painted by Piguenit and photographed by Beattie.[24] A fringe of dead trees around the lake’s edge now greeted visitors. When photographers Stephen Spurling III and Frank Hurley joined the National Park Board in attacking the Hydro, Minister for Lands and Works Major TH Davies sprang to the institution’s defence, describing the damage as ‘unavoidable’.[25] This was a taste of what was to come at Cataract Gorge, Lake Pedder, the Pieman River and the Lower Gordon River.

Excision of the Wolfram Mine

With rearmament taking place in Europe in 1938, the raised price of tungsten (wolfram), used for strengthening steel, prompted an application to reopen the (Mount Oakleigh) Wolfram Mine, which was then included in the Cradle Mountain Reserve. CMRB Secretary Ron Smith penned the board’s opposition to the proposal, stating that no payable lode was likely to be found and that a successful application would set a bad precedent in terms of mining the reserve.[26] The subsidiary board’s concerns were not heeded. In a forerunner to national park and/or Wilderness World Heritage Area excisions at Mount Field, the Hartz Mountains and Exit Cave, the mine was temporarily excised from the scenic reserve as the Mount Oakleigh Conservation Area.[27] No Tasmanian reserved land ever seemed inalienable after this.

The Mount Kate sawmill dispute and dissolution of the CMRB

The pitfalls of having vested interests on a government board again became apparent in December 1943 when Ron Smith took advantage of wartime stringency, rising timber prices and a finished access road to start harvesting King Billy pine on his property at Mount Kate. Over the next few years the definition of conflict of interest and the limits of official jurisdiction became increasingly blurred, as private land was resumed at Cradle Valley and the problematic CMRB was dissolved. Ironically, Smith and the Launceston syndicate had previously offered their land to the government but been refused. With Waldheim compulsorily acquired, Lionel Connell resigned as ranger. His sons Esrom and Wal were later reemployed in their own right as rangers at Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair. The appointment of the Cradle Mountain National Park Board in 1947 was the first step in placing the national park—as it was now known for the first time—on a sound footing, 25 years after the scenic reserves were initially gazetted. But the battle of ecology and economy continued.

[1] Gerard Castles, ‘Handcuffed volunteers: a history of the Scenery Preservation Board in Tasmania 1915–1971’, BA (Hons) thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 1986.

[2] This was the Scenery Preservation Act (1921). For an example of fears of loggers being locked out of the Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair Scenic Reserves, see E Alexander, ‘Cradle Mountain park: claims of timber area’, Advocate, 22 August 1921, p.5.

[3] ‘Fur farming: Cradle Mountain unsuitable: area further south chosen’, Mercury, 17 August 1925, p.6.

[4] ‘Lure of the skins’, Advocate, 22 August 1925, p.12.

[5] Statistics of Tasmania, 1922–23, p.58.

[6] Proclamation, Tasmanian Government Gazette, 8 March 1927, p.753.

[7] Proclamation, Tasmanian Government Gazette, 31 May 1927, pp.1412–13.

[8] Gerald Propsting to the secretary for Public Works, 4 August 1927, AA580/1/1 (TA); ‘Game Protection Act: illegal possession of skins’, Mercury, 17 August 1927, p.5.

[9] Fred Smithies, transcript of an interview by Margaret Bryant, 15 June 1977, NS573/3/3 (TA).

[10] Weekly Courier, 8 August 1928, p.1.

[11] Ron Smith to National Park Board Secretary Clive Lord, 27 August 1928, NS234/19/1/20 (TA).

[12] Paddy Hartnett to ET Emmett, 26 November 1928, PWD24/1/3; Director of Public Works to LM Shoobridge, Chairman of the National Parks Board, 13 March 1931, NS234/17/1/17 (TA).

[13] Bert Nichols to Ron Smith, 26 April 1931, NS573/1/1/4 (TA).

[14] Kevin Anderson, ‘Tasmania revisited: being the diary of Kevin Anderson, in which he related the incidents of his travelling to and through Tasmania with his companion, William Foo, from 12th April 1939 to the 26th April 1939’, unpublished manuscript (QVMAG), p.27.

[15] Jessie Luckman interviewed by Nic Haygarth.

[16] Bernard Stubbs interviewed by Nic Haygarth, c1993; Esrom Connell, in writing to Percy Mulligan, 20 September 1963 (NS234/19/122, TA), claimed to possess a diary in which Weindorfer recorded the failure of the motorbike to start. The present whereabouts of the diary are unknown. For the coronial inquiry into Weindorfer’s death, see AE313/1/1 (TA). The coroner determined the cause of death to be heart failure.

[17] ‘Papers relating to Coronial Enquiry into death of Gustav Weindorfer’, AE313/1/1 (TA).

[18] On 17 April 1928 Weindorfer wrote in his dairy, ‘This is very likely my last trip on the mountain’ (QVMAG). If he had a buyer for Waldheim then, the deal must have fallen through.

[19] Public Trustee to Fred Smithies, 11 November 1932, NS573/1/1/7 (TA).

[20] Minutes of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board meeting, 26 April 1935, AF363/1/1, p.185 (TA).

[21] Ron Smith diary, 1940, NS234/16/1/41 (TA).

[22] Jessie Luckman interviewed by Nic Haygarth.

[23] ‘Cradle Mountain’, Advocate, 31 July 1922, p.2.

[24] ‘Level of water raised’, Mercury, 12 October 1938, p.13.

[25] National Park Board: ‘Level of water raised’, Mercury, 12 October 1938, p.13; Davies: ‘Lake St Clair: high level “unavoidable”’, Advocate, 13 October 1938, p.6; Hurley: ‘Tasmanians asleep’, Mercury, 30 January 1939, p.8; Spurling: S Spurling, ‘Scenic vandalism’, Examiner, 5 October 1940, p.3.

[26] Ron Smith to Minister for Mines, 3 May 1938, NS234/19/1/4 (TA).

[27] For an overview of the Wolfram Mine dispute, see Gerard Castles, ‘Handcuffed volunteers: a history of the Scenery Preservation Board in Tasmania 1915–1971’, pp.51–52.