In November 1926 a Mrs Gresson advertised tourist accommodation at the Tasmanian mining settlement of Adamsfield: ‘See Tasmania’s Wild West, the “osie” diggers, Adams Falls, Gordon Gorge’.[1] What extraordinary enterprise for a simple digger’s wife 120 km west of Hobart! However, when you learn what an extraordinary woman Lily Gresson actually was, this visionary behaviour comes as no surprise at all.

Her old school Airbnb advert was probably shaped by two events: meeting the one-man promotional band Fred Smithies; and a memorable outing she made to the nearby Gordon River Gorge. Visiting Adamsfield by horseback and pack-horse in February and March 1926, Smithies, an amateur tourism promoter, had snapped the town and its jagged skyline for his travelling lantern-slide lecture ‘A trip through the wilds of the west coast and the osmiridium fields’. ‘Gorges of inspiring grandeur’ and ‘magnificent mountain scenes’ also transfixed Gresson. Decades later she recalled that

‘the scenery to the Gordon River was indescribable. Peak after peak of snow-capped mountains and the Gordon Gorge was so precipitous we would scarcely see the bottom … [it] … was like so many battlements’.

Her party ‘cheerfully stalked along the ten miles of wonderful scenery singing bits of popular songs. This was the first time I had heard [‘]Waltzing Matilda[’], she recalled, ‘and it certainly cheered and helped us along, and home again, when we’—Lily and her husband Arthur Gresson, a veteran of the Siege of Mafeking during the South African War— ‘were beginning to flag’.[2]

Certainly the outing would have come as welcome relief from the routine of life on the Adamsfield diggings. The Gressons had rushed to Adams River in the spring of 1925, after the Staceys from the Tasman Peninsula and their mates struck payable osmiridium. Lily was a woman of great conviction. At a time when few women dared venture among the thousand or so men on the ossie field, she secured her own miner’s right, put together a side of bacon and other requisites, bundled her twelve-year-old son Wrixon onto the train and off they went to Fitzgerald, the western terminus of the Derwent Valley Line, to join Arthur.

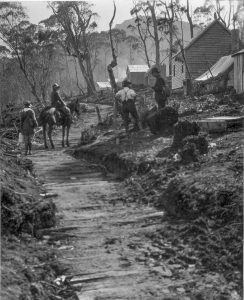

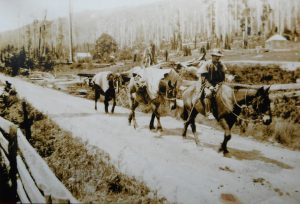

Fitzgerald was still 42 km from Adamsfield. Meeting his family there, Arthur hired five horses, including one for Wrixon, who had never ridden a horse before, one for the packer and another to carry the three months’ supply of food and equipment. It was snowing. In parts of the Florentine Valley the mud was up to the horses’ girths, Lily recalled,

‘and they slithered, slipped and plunged into the side track to keep themselves steady. The track was narrow, hastily prepared in very thick scrub, corduroyed also hurriedly—the edges not even adzed. I pitied the poor ‘gees’ [horses] slipping and floundering to try and gain firm footing. I thought I would soon be slipping over their heads and called out to my husband, “Shall I dismount?” “Certainly not”, was the reply, “or you will never get up again.” So I stayed on as best I could following the packer’s lead, for I was behind him. Presently, just around the corner, he shouted, “Look out, the down packs are coming!”’[3]

This was pack horses returning unsupervised from Adamsfield. When the osmiridium field was reached, the horses were simply released to find their own way back down the track to Fitzgerald. Given that there was no feed between the two centres, the hungry animals galloped wherever they could, a nasty surprise for the uninitiated coming the other way. How the horses survived the return trip without a broken leg is hard to imagine.

The Gresson party stopped for the night at Chrisp’s Hut, a leftover from the 1907 Great Western Railway Survey.[4] It took a further day to reach Adamsfield over the ranges. The mining settlement was ‘a busy seething mass of men and horses, to say nothing of a vast morass of mud, with short stumps sticking up everywhere, quite enough to topple us over’. Arthur Gresson was living in the sort of tent-hut typical of a temporary miner’s quarters. Wrixon slept on a bench in a bark humpy with only a hessian curtain to keep out the cold, while his parents bunked down under a tent fly.

Having obtained the miner’s right, Lily was entitled to peg her own claim measuring 50 yards by 50 years (that is, about 45 metres square), and she set out next morning suitably attired in her lace-up mining boots, riding breeches, short coat and emerald-green rain hat. After she had dug a hole almost two metres deep and obtaining osmiridium-bearing earth, a man ‘jumped’ her claim, taking all the valuable ‘wash’ before she even knew it had happened. Arthur Gresson sent the intruder packing, but the damage was done, and Lily had to start again on a new claim. Soon she was winning tiny nuggets of coarse ‘metal’ by sluicing the ‘wash-dirt’.[5]

The Gressons remained at Adamsfield through the tough winter of 1926, when the diggers tried to counteract a reduced osmiridium price by selling their metal directly to London. It was tough going through that winter. Many left the field, while others stayed and suffered. Lily recalled the time nineteen-year-old digger Maxwell Godfrey went missing on an icy-cold night. He curled up under a log in the bush, but his legs were frostbitten. Nurse Elsie Bessell, who had only a tent for a hospital, could do little for him, and the news got no better after he was stretchered out to Fitzgerald, slung between two horses. Both his legs were amputated below the knee.[6] A public subscription raised about £500 to help him, and soon he was walking again with the aid of prosthetics.[7]

Lily Gresson, who had had some nursing experience in London, again showed her versatility by looking after the two patients in the hospital while Nurse Bessell accompanied the incapacitated man out to the railway station. Perhaps Lily also home schooled thirteen-year-old Wrixon. There were few children and no school at Adamsfield at this time, so otherwise he would have lost a year of his education.

And the Gressons’ Air B’n’B house? Well, while it was hardly the Adamsfield Hilton, it was comfortable enough by mining frontier standards—a paling hut with a big fireplace and a real glass window.[8] Lily Gresson might have been just a little ahead of her time. Hikers would soon be on their way to Adamsfield and the glorious south-west beyond. Ernie Bond would be besieged with them at times on his Gordon River farm, Gordon Vale, during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1952 the Launceston and Hobart Walking Clubs would even inherit Gordon Vale. Lily Gresson , pioneer of the Adamsfield diggings, was onto something!

With thanks to Dale Matheson, who showed me this story.

[1] ‘Board and residence’, Mercury, 23 November 1926, p.1.

[2] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, the author, 1987, p.194.

[3] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, p.190.

[4] In her account, Lily Gresson did not mention the notorious ‘Digger’s Delight’, the sly-grog shop and accommodation house that accompanied Chrisp’s Hut soon after the Adams River rush began. Perhaps Ralph Langdon and Bernie Symmons had already moved on into down-town Adamsfield, building Symmons Hall with its accompanying illegal boozer.

[5] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, p.192.

[6] ‘Bush nursing’, Mercury, 22 July 1926, p.11; Elsie G Bessell, quoted by Marita Bardenhagen, Adamsfield bush nursing paper, presented at the Australian Mining History Association conference at Queenstown, 2008; ‘Sufferer in bush’, Mercury, 24 May 1928, p.5.

[7] ‘Maxwell Godfrey Fund’, Mercury, 27 July 1927, p.3; ‘Maxwell Godfrey walks again’, and ‘Sufferer in bush’; both Mercury, 24 May 1928, p.5.

[8] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, p.192.