The diggers were grizzling. In 1921 Tasmania enjoyed a world monopoly on ‘point metal’ osmiridium, that is, osmiridium grains that were just the right size to fuse onto the nibs of gold fountain pens. The ossie price was generally high. Tasmania’s niche in the market was unchallenged. The diggers on the fields west and south-west of Waratah should have been happy.

They weren’t. Part of the problem was that few had a grasp of economics. They did not understand that they dampened demand by rushing their ore to market. Remotely located diggers working alone felt cut off from the metal market. Some were convinced that they were the victims of collusion between precious metal buyers who were determined to force down the price.

Calls for government to intervene in the market were finally answered when Premier Sir Walter Lee agreed to introduce an experimental monopoly. As of 1 January 1922, precious metals dealer Overell & Sampson held the only Tasmanian osmiridium buyer’s licence—so now there could be no collusion. Could the company get the diggers a better price for their metal? Almost 250 men banked on it, selling their osmiridium through the government scheme. The list of sellers compiled on 30 June 1922 is now a handy checklist for historians and genealogists. Here are the men in one long list by rough alphabetical order as set out in the government records.[1] My only addition is some comments in the column at right.

| Name | Value of os (£, s & d) | Weight of os (oz, dwts & grains) | Comments |

| Anderson, Thomas | 35-15-7 | 2-3-9 | |

| Aylett, George | 40-11-3 | 2-7-5 | |

| Aylett, William | 85-9-8 | 5-0-12 | Later at Adamsfield |

| Allan, G & W | 97-10-7 | 5-10-1 | |

| Allan, BJ | 40-10-0 | 2-0-12 | |

| Allan, J | 40-0-0 | 2-0-0 | Jim Allan, Nineteen Mile Creek |

| Baptist, J | 50-0-0 | 3-14-21 | John D’Ahren Baptiste, aka Hooky Jack, later at Adamsfield. |

| Baptist, J (Reserve) | 100-5-0 | 5-0-6 | |

| Beale, W | 30-6-6 | 1-14-8 | |

| Berryman, E | 133-7-10 | 8-18-17 | |

| Berkery, M | 27-18-7 | 1-12-0 | |

| Buckingham, H | 11-3-3 | 0-11-20 | |

| Betts, WA | 46-14-4 | 3-1-23 | Betts Track named after a Betts prospector. |

| Biggins, Norman | 26-5-0 | 1-15-0 | |

| Billinghurst, J | 20-11-0 | 1-3-16 | |

| Booth, George | 31-18-9 | 2-2-14 | |

| Booth, William | 45-2-5 | 2-17-4 | |

| Boyd, H | 53-6-0 | 3-5-11 | |

| Brown, G | 20-0-0 | 1-19-21 | |

| Bryant, JH | 71-8-9 | 4-13-14 | Former Derby shopkeeper. Committee member of the osmiridium pool. |

| Burness, J | 16-15-0 | 1-2-8 | |

| Burness, Charles | 18-5-0 | 1-4-8 | |

| Brettoner, JE | 18-5-0 | 1-4-8 | |

| Blake, UJ | 12-12-3 | 0-16-3 | |

| Bosich, L | 13-15-0 | 0-18-8 | |

| Brodie, W | 1-11-8 | 0-1-14 | |

| Button, A | 47-19-5 | 2-9-18 | |

| Booth, George Jnr | 32-9-2 | 1-12-11 | |

| Burge, J | 11-14-2 | 0-11-17 | |

| Burke, RH | 2-11-0 | 0-3-0 | |

| Bynon, R | 42-11-3 | 2-5-17 | |

| Blair, F | 8-0-0 | 0-8-0 | |

| Burness, HB | 21-5-0 | — | |

| Callaghan, B | 75-13-6 | 4-10-12 | |

| Carpenter, T | 53-18-4 | 3-6-18 | |

| Carmody, H | 37-0-0 | 4-0-0 | |

| Clementson, M | 13-3-5 | 1-3-15 | Matty Clementson, ‘the [Mount] Stewart king’. |

| Coghlan, J | 17-0-0 | 0-17-0 | |

| Crawford, T | 53-0-7 | 5-10-5 | |

| Casey, W | 75-0-7 | 4-0-13 | |

| Casey, W | 43-14-11 | 2-18-8 | |

| Cashman, John | 39-18-2 | 2-9-15 | |

| Caudry, William | 15-0-0 | 1-0-0 | Caudry’s Reward reef mine, Caudrys Hill, the first mine of its kind in the world. Also had a lease at Mount Stewart. |

| Caudry, William | 100-0-0 | 5-0-0 | |

| Caudry, Thomas | 62-17-6 | 3-2-21 | Brother of William Caudry. |

| Cooney, J | 45-17-6 | 2-5-21 | |

| Cumming, R | 47-19-7 | 2-9-18 | |

| Chellis, WH | 128-11-8 | 6-8-14 | Walter Chellis, Castray River, champion axeman & publican. |

| Cook, Henry | 48-13-10 | 2-18-2 | |

| Cady, W | 31-7-8 | 1-16-22 | |

| Davidson, J | 19-0-7 | 1-2-3 | Jack Davidson, stalwart of the Nineteen Mile. |

| Devlyn, Fred | 73-9-6 | 4-0-3 | |

| Devereaux, H | 28-9-7 | 1-12-3 | |

| Dixon, J | 49-4-7 | 2-15-15 | |

| Doak, William | 5-18-9 | 0-7-23 | Doaks Creek at Adamsfield named after him. |

| Doran, William | 47-14-7 | 3-0-7 | |

| Donovan, D | 42-0-0 | 2-6-0 | |

| Dhu, Hugh | 47-2-4 | 2-14-20 | |

| Dunn, Steve | 34-8-6 | 2-0-12 | |

| Drew, M | 21-11-7 | 1-5-16 | |

| Duffy, James & Manion, Thomas | — | 1-2-0 | |

| Devlyn, John | 6-5-7 | 0-8-9 | |

| Dixon, TF | 12-13-2 | 0-16-8 | |

| Dwyer, S | 42-11-10 | 2-13-4 | Sammy Dwyer, from NSW, last man at the Nineteen Mile, 1950s |

| Duffy, J | 27-4-2 | 1-14-23 | |

| Dunn, John | 23-13-4 | 1-3-16 | |

| Donohue, J | 18-16-0 | 1-0-6 | |

| Davies, D | 20-6-6 | 1-2-3 | |

| Dickson, C | 42-10-7 | 2-5-16 | |

| Davie, A | 48-10-0 | 2-10-0 | Probably Arthur Davey, one of the stalwarts of the Nineteen Mile. |

| Dettoner, AC | 11-12-4 | 0-11-16 | |

| Davies, C | 25-0-0 | 1-5-0 | |

| East, G | 61-16-8 | 5-5-20 | |

| Easther, C & Garrett, T | 100-4-2 | 5-0-5 | |

| Easther, C | 52-4-7 | 4-16-8 | |

| Eastwood, William | 38-16-8 | 2-13-2 | |

| Elmer, William | 57-19-1 | 4-6-9 | |

| Ellims, V | 79-19-0 | 4-11-18 | |

| Evans, Charles | 58-10-7 | 3-8-3 | ‘Chillie’ Evans, a well-known digger. |

| Eames, G | 71-10-7 | 4-0-15 | Jones Creek digger George Eames, whose dealings with osmiridium buyer Robert Krebs in 1923 helped bring down the government monopoly scheme. |

| Etchell, Thomas | 18-16-3 | 1-4-10 | Brother of well-known bushman, Luke Etchell, with whom he lived at Guildford. They were also pulp wood cutters and snarers. |

| Fenton, S | 58-18-1 | 3-6-23 | |

| Ferguson, WJ | 18-5-5 | 3-4-6 | |

| Flowers, S | 31-17-0 | 3-5-19 | |

| Forbes, A | 47-5-0 | 6-3-0 | |

| Finlay, R | 50-19-10 | 2-12-7 | |

| Fenton, AW | 43-2-6 | 2-13-13 | |

| Ferrari, S | 99-3-11 | 5-5-8 | |

| Frazer, JD | 10-8-3 | 0-11-21 | John D ‘Scotty’ Frazer, a well-known digger who disappeared in the bush in 1923, thought to have drowned. |

| Findon, John | 14-0-0 | 0-14-0 | |

| Fahey, James | 69-8-4 | 4-0-17 | |

| Farquhar, John | 27-4-8 | 1-8-8 | |

| Flight, W | 12-18-6 | 0-15-5 | |

| Finlay, JH | 1-18-4 | 0-1-22 | Jack Finlay, remembered by osmiridium fields poet Mulga Mick O’Reilly as ‘Jack Fennelly’. |

| Garratt, T | 52-4-7 | 4-16-8 | Probably Tyson Garrett of Savage River. |

| Grant, William | 19-9-1 | 1-3-6 | |

| Grant, Charles | 43-10-6 | 2-8-12 | |

| Grills, H | 51-15-8 | 3-19-4 | |

| Grosser, PA | 79-11-0 | 4-15-0 | Magnet’s Phil Grosser, of Mount Stewart and the Nineteen Mile, later at Adamsfield. |

| Grubb, John | 18-16-4 | 1-0-9 | |

| Gould, J | 21-1-2 | 1-2-17 | |

| Gatehouse, H | 79-11-8 | 3-19-14 | |

| Gurney, C | 3-3-0 | 0-3-17 | |

| Harper, Thomas | 25-8-8 | 1-9-3 | |

| Hamilton, William | 21-7-6 | 1-11-17 | |

| Harrison, J | 25-0-0 | 4-16-3 | Is this Wynyard’s James ‘Tiger Cat’ Harrison, real estate agent, ‘human cork’ and prospector, who dealt in live marsupials, including thylacines? |

| Henderson, C | 14-11-10 | 0-18-18 | |

| Hines, William J | — | 0-12-7 | |

| Hodson, H | 17-3-3 | 1-1-5 | |

| Hughes, Victor | 24-14-9 | 3-8-5 | |

| Humphries, Albert | 43-12-3 | 2-11-16 | |

| Humphries, Albert | 36-6-10 | 1-19-12 | |

| Humphries, R | 52-0-10 | 3-6-1 | Probably Magnet resident Robert Humphries, of the Mount Stewart field. |

| Hancock, J | 31-13-10 | 2-0-5 | Probably Jos Hancock, of Flea Flat, Nineteen Mile Creek, whose hut was used as a location in the movie Jewelled Nights in 1925. |

| Hanlon, T | 93-8-3 | 5-5-22 | |

| Harvey, Joseph | 72-17-7 | 4-9-0 | |

| Humphries, HH | 34-18-4 | 1-14-22 | |

| Harrison, M | 32-0-0 | 1-12-0 | |

| Hope, A | 22-1-8 | 1-2-2 | |

| Hollow, J | 43-4-2 | 2-3-5 | |

| Hill, Kenneth | 19-8-0 | 1-3-10 | |

| Inglis, AL | 33-6-8 | 1-13-8 | |

| Inglis, AL | 208-0-0 | 10-0-0 | |

| Jones, RW | 100-0-0 | 10-0-0 | Probably Robert Walter Jones, aka Wally Jones, who later went to Adamsfield and was osmiridium buyer HB Selby & Co’s agent there. |

| Jones, CH | 22-14-4 | 1-10-7 | |

| Jans, FC | 77-6-5 | 4-6-0 | Fred Jans, later at Adamsfield, where he died in 1944. |

| Johnston, L | 31-15-0 | 1-11-18 | |

| Jones, TH | 60-0-0 | 3-0-0 | Possibly Tom Jones, after whom Jones Creek was named. |

| Jones, John | 16-0-1 | 0-17-16 | |

| Jenner, H | 8-5-6 | 0-8-12 | Harry Jenner, later at Adamsfield. |

| Keltie, William | 18-3-11 | 1-2-23 | |

| Kenny, J | 57-17-6 | 4-7-9 | |

| Kinsella, A | 39-2-8 | 2-8-21 | Possibly related to Bill Kinsella of Wilson River. |

| Kelcher, John | 38-9-11 | 2-10-2 | |

| Knight, W | 16-18-7 | 0-19-22 | |

| Kelly, James | 16-18-5 | 1-2-13 | |

| Keenan, C | 22-16-8 | 1-2-20 | |

| Kershaw, F | 11-19-5 | 0-14-2 | |

| Lane, R | 31-14-4 | 1-15-15 | Roger Lane, who worked with the Maywood brothers at the Nineteen Mile. |

| Leary, M | 34-6-3 | 2-11-14 | |

| Long, Thomas | 32-3-11 | 2-0-7 | |

| Long, Thomas | 27-3-10 | 1-8-7 | |

| Leach, George | 10-1-10 | 0-11-21 | |

| Loughnan, E Jnr | 50-15-7 | 3-6-17 | ‘Peg Leg Ted’, one of the discoverers of payable osmiridium at Mount Stewart. Had a prosthetic leg. Loughnan Creek is named after him. |

| Loughnan, James | 54-3-5 | 3-8-10 | |

| Lyons, T | 3-15-0 | 0-5-0 | |

| Loughnan, E Snr | 42-16-3 | 2-17-2 | |

| Llewellyn, John | 47-0-0 | 2-15-0 | |

| Loughnan, George | 51-5-11 | 2-14-18 | |

| Mackersey, L | 24-1-8 | 1-18-0 | |

| Maywood, A | 32-14-2 | 2-9-13 | Brother of Ted Maywood, with whom he worked at the Nineteen Mile, along with Roger Lane. |

| Maywood, E | 16-10-0 | 1-10-11 | Ted Maywood, who worked at the Nineteen Mile with his brother and Roger Lane. |

| Mills, James & Jenner, H | — | 1-3-4 | |

| Mills, J | 57-16-3 | 4-15-18 | |

| Mills, J | 19-2-6 | 1-2-12 | |

| Moore, A | 28-16-8 | 3-14-5 | Probably Savage River digger Albert Moore, brother of Reuben Moore. |

| Morgan, William | 87-8-0 | 5-11-12 | |

| Moore, RR | 74-3-9 | 4-3-17 | Probably osmiridium digger and buyer Reuben Moore, who died at Savage River in 1925. |

| Moffitt, LJ | 53-15-10 | 2-13-19 | |

| Martin, J | 6-0-0 | 0-6-0 | |

| Manion, Thomas | 26-4-2 | 1-12-23 | From the Beaconsfield family of Manions? |

| Mallinson, RD | 17-0-0 | 0-17-0 | |

| Meares, RK | 11-11-7 | 0-13-15 | |

| Matthews, T | 15-0-4 | 0-17-16 | Possibly ‘Winger’ Matthews, who appeared in Marie Bjelke Petersen’s novel Jewelled nights as ‘Wingy’ Matthews. |

| Major, J | 85-2-10 | 5-0-4 | |

| McAvoy, D | 82-1-11 | 5-19-1 | |

| McAidell & Hill | Probably CL McArdell and Harry Hill, the latter being a well-known digger who was later at Adamsfield. | ||

| McCaughey, LB | 37-3-1 | 2-4-20 | |

| McDiamid, William | — | 0-10-0 | |

| McGuiness, A | 32-2-9 | 1-18-19 | |

| McGuire, J | 44-18-9 | 3-14-12 | |

| McCormack, Charles | 33-5-0 | 2-4-8 | |

| McGuiness, F | 28-4-1 | 1-10-21 | |

| McCaughey, M | 43-14-4 | 2-8-6 | |

| McCaughey, William | 15-14-9 | 0-16-14 | |

| McQueeny, F | 11-14-2 | 0-11-17 | |

| McArdell, CL | 30-19-9 | 1-16-11 | |

| McDonald, Alex | 8-10-0 | 0-10-0 | Of Flea Flat, Nineteen Mile Creek, where he shared a hut with Jim McGinty until the latter’s death in 1920. |

| Newman, M | 21-15-9 | 1-5-9 | |

| Newman, M | 37-18-7 | 2-4-15 | |

| Nelson, H | 40-0-0 | 2-0-0 | |

| Osborn, WH | 44-4-3 | 2-13-10 | |

| Oakley, H | 21-16-4 | 1-8-1 | |

| Oakley, J | 38-5-11 | 2-12-4 | |

| Oakley, H & Loughnan, J | 7-10-0 | 0-10-0 | |

| Oakley, RP | 9-18-1 | 0-13-5 | |

| Papworth, S | 40-0-0 | 4-0-0 | Later of Adamsfield. |

| Pearson, Robert | 103-15-8 | 6-0-6 | |

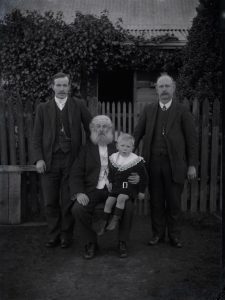

| Prouse, Charles A | 141-8-0 | 8-9-10 | Charles Arthur Prouse, son of Tom Prouse. Together in 1922 they were pictured with two large nuggets found on the upper Nineteen Mile, the one found on the dump by his father being a record 4.5 oz. Charlie Prouse later went on to Adamsfield, where he was the first bride groom on the field, marrying the bush nurse, Constance Brownfield, in 1928. Also an osmiridium buyer at Adamsfield. |

| Prouse, William | 67-9-5 | 3-12-10 | |

| Parsons, Norman | 35-12-6 | 2-7-12 | From Caveside, was part of the syndicate trying to work a hydraulic show at the Little Wilson River. |

| Prouse, J | 78-16-7 | 4-5-8 | |

| Paine, Hy | 16-18-5 | 1-2-14 | Possibly Harry Reginald Paine, later the author of a book about Waratah, Taking you back down the track … |

| Paine, W | 18-8-4 | 0-18-10 | |

| Power, T | 18-10-0 | 0-18-12 | |

| Prouse, H | 20-4-0 | 1-2-14 | |

| Paine, Thomas | 51-7-6 | 2-11-9 | |

| Reimers, J | 36-5-0 | 3-3-6 | |

| Richardson, A | 47-15-0 | 4-2-3 | |

| Richards, J | 48-10-10 | 4-12-22 | |

| Ruggeri, R | 27-12-8 | 1-12-13 | |

| Russell, J & Casey, W | — | 2-6-12 | |

| Russell, J | 67-5-7 | 3-12-19 | Osmiridium pool committee member. |

| Russell, J | 43-14-4 | 2-18-7 | |

| Ramsay, James | 62-17-6 | 3-2-21 | |

| Ruffin, H | 36-10-0 | 1-16-12 | |

| Rearden, S | 6-18-1 | 0-8-3 | Syd Reardon, from Lorinna, alcoholic prospector. |

| Schill, F | — | 1-7-0 | |

| Shea, M | 79-16-8 | 4-9-20 | |

| Sheedy, Chris | 39-15-9 | 4-7-4 | Secretary of the osmiridium pool. |

| Sims, W | 12-14-7 | 1-6-1 | |

| Simpson, PC | 34-5-6 | 1-17-21 | |

| Stanley, H | 58-11-1 | 3-13-20 | |

| Smith, WH | 34-0-0 | 2-0-0 | |

| Smith, R | 70-0-5 | 4-17-22 | |

| Spencer, T | 81-2-6 | 7-1-3 | |

| Sutton, WH | 7-17-6 | 0-10-12 | |

| Stanton, JM | 65-10-11 | 3-16-19 | Reward lease holder (with Edward Loughnan jnr) at Mount Stewart. |

| Symons, GC | 15-0-0 | 1-0-0 | |

| Spencer, John | 88-8-1 | 5-6-18 | |

| Stebbings, A | 74-6-8 | 4-6-13 | |

| Shady, William | 30-5-0 | 2-0-8 | William Antonio Shady, son of Syrian hawker and shopkeeper Antonio Shady, osmiridium buyer. Became a Waratah storekeeper. |

| Smith, Martin | 38-7-11 | 2-6-1 | |

| Sullivan, J | 36-1-4 | 2-1-11 | |

| Symons, James B | 45-18-4 | 2-11-22 | |

| Symons, James B | 105-0-0 | 7-0-0 | |

| Shaw, Thomas | 114-2-2 | 6-13-17 | |

| Sewell, J | 8-2-6 | 0-8-3 | |

| Spencer, James | 25-7-6 | 1-5-9 | |

| Symons, Charles & George | 154-10-0 | 7-14-12 | |

| Scoles, J | 6-8-11 | 0-7-14 | |

| Symons, Charles | 81-5-7 | 4-15-15 | |

| Thomas, T | 15-7-5 | 0-18-2 | |

| Thurstans, F | 61-14-3 | 4-10-15 | |

| Thorne, A | 66-7-9 | 5-6-4 | |

| Thorne, Charles | 95-4-11 | 5-10-20 | |

| Thorne, W | 33-6-9 | 2-3-4 | |

| Tudor, Lionel | 91-4-8 | 6-18-3 | |

| Tudor, Lionel | 110-5-0 | 7-7-0 | |

| Tunbridge, E | 39-3-9 | 2-17-6 | |

| Turner, H | — | 1-12-11 | |

| Taylor, James | 18-5-0 | 1-4-8 | |

| Tudor, Henry | 111-2-2 | 6-2-8 | |

| Thorne, Harold | 12-12-8 | 0-14-13 | |

| Thorne, H & W | 44-5-0 | 2-8-12 | |

| Venville, D | 36-19-2 | 2-7-12 | |

| Watkins, J | 24-15-7 | 1-8-6 | |

| Wilson, R | 54-0-0 | 4-0-12 | |

| Wilson, W | 37-17-6 | 2-10-12 | |

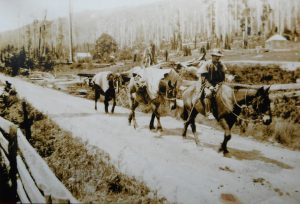

| Whyman, Victor | 59-12-1 | 3-14-22 | Driver for his brother Ray Whyman, storesman and packer on the osmiridium fields. Claimed to be the model for the singing driver in Marie Bjelke Petersen’s novel Jewelled nights. |

| Whyman, Arthur | 30-11-3 | 2-0-18 | |

| Whyman, Phillip | 52-6-8 | 2-17-8 | Proprietor of the Bischoff Hotel. |

| Wilson, J | 35-8-3 | 2-1-12 | |

| Wilson, Percy W | 34-18-1 | 2-3-21 | |

| Woolley, James | 4-12-1 | 0-5-9 | |

| Walters, WA | 25-8-4 | 1-5-10 | |

| Wragg, H | 12-10-0 | 0-12-12 |

[1] From AB948/1/98 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).