by Nic Haygarth | 08/12/18 | Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray reckoned that thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) followed him when he walked from Magnet to Waratah in the state’s far north-west—out of curiosity, rather than malicious intent. If he swung around suddenly he could catch a glimpse of one.[1] However, Cutter did better than that. In 1925 he caught a tiger alive and took it for a train ride to Hobart.

Tigers are just one element of the twentieth-century tale of Cutter and his elder brother Basil Murray. Yet for all their exploits these great high country bushmen started in poverty and rarely glimpsed anything better. Cutter married and produced a family, but his weakness all his working life was gambling: what he made on the possums (and tiger) he lost on the horses. Basil made enough money to keep the taxman guessing but was content to live out his days in a caravan behind Waratah’s Bischoff Hotel.[2]

Their ancestry was Irish Roman Catholic. Basil Francis Murray (1893–1971) was born to Emu Bay Railway ganger Edward James (Ted) Murray and Martha Anne Sutton. He was the couple’s ninth child. Arthur Royden Murray (1898–1987?) was the twelfth.[3] Three more kids followed. The family lived at the fettlers’ cottages at the Fourteen Mile south of Ridgley while Ted Murray was a ganger, but in 1907 he became a bush farmer at Guildford, renting land from the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co).[4] Guildford, the junction of the main Emu Bay Railway line to Zeehan and the branch line to Waratah, had a station, licensed bar and state school, but was also a centre for railway workers, VDL Co timber cutters and hunters. Edward Brown, the so-called ‘Squire of Guildford’, dominated local activity.

Guildford Junction State School, with teacher May Wells at centre. From the Weekly Courier, 10 November 1906, p.24.

Squaring sleepers, splitting timber, hunting, fencing, scrubbing out bush, driving bullocks, herding stock, milking cows and setting snares were essential skills for a young man in this locality. Like others, the Murrays snared adjoining VDL Co land, paying the company a royalty. Several Murray boys escaped Guildford by serving in World War One, but Cutter recalled that his father would not let him enlist.[5] Basil also stayed home.[6] Perhaps it was enough for Ted and Martha Murray that they lost one son, Albert Murray, killed in action in France in 1916.[7]

Guildford Railway Station during the ‘great snow’, 1921. Winter photo, Weekly Courier, 18 August 1921, p.17.

Guildford Station under snow again, 24 September 1930. RE Smith photo, courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Twenty-three-year-old Arthur Murray appears to have married Alice Randall in Waratah during the ‘great snow’ of August 1921. He would already have been a proficient bushman. Cutter learned to use the treadle snare with a springer, although he would also employ a pole snare for brush possum and would shoot ringtails. He shot at night using acetylene light to illuminate the nocturnal ringtails, but he found it easier to go after them by day by poking their nests in the tea-tree scrub. ‘It was like shooting fish in a barrel’, Cutter’s son Barry Murray recalled. ‘It was only shooting as high as the ceiling … A little spar and you just shook it … and they’d come out, generally two, a male and a female …’[8] Hunters aimed for the nose so as to keep the valuable fur untainted.

In the bush Cutter lived so roughly that no one would work with him. Some tried, but none of them lasted. His huts and skin sheds on the Surrey Hills were little more than a few slabs of bark. Friday was bath day, which meant a walk in Williams Creek (east of the old Waratah Cemetery), regardless of weather conditions. Cutter’s son Val once snared Knole Plain with him, but couldn’t keep up. Snares had to be inspected every day, the game removed, and the snares reset. Cutter and Val took snaring runs on opposite sides of the plain, but Val found that even if he ran the whole way and didn’t reset any snares, Cutter would be sitting waiting for him, having long completed his side.

Cutter’s most substantial skin shed was near home base, on the hill above the primary school at Waratah. Here he would smoke the skins before an open fire. He pegged them out both on the wall and on planks about eighteen inches wide, each plank long enough to accommodate three wallaby skins. When the sun shone, he took the laden planks outside; otherwise he sat inside the skin shed with his skins, chain smoking cigarettes in empathy. A skin shed had no chimney, the idea being that the smoke would brown the skins as it escaped through the cracks between the planks of the walls. The air was so black with smoke that Cutter was virtually invisible from the doorway.[9] Yet no carcinogens prevented him reaching his eighties.

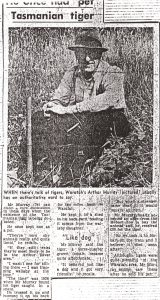

Joe Fagan claimed that Basil Murray was such a good snarer that he once snared Bass Strait.[10] Basil preferred the simple necker snare to the treadle, and caught a tiger in such a device on Murrays Plain, a little plain above the 40 Mile mark on the railway named after Ted Murray.[11] Cutter caught a couple of three-quarters-grown tigers. One was taken dead in a treadle snare with a springer on Goderich Plain when Cutter was hunting with Joe Fagan.[12] Joe kept the skin for years as a rug, but when it grew moth-eaten he tossed it on the fire—oblivious to its rarity or future value.[13] Cutter caught the other thylacine alive in a treadle near Parrawe.[14] He trussed her up and humped her home, where ‘a terrific number of people’ came for a look.[15] ‘They’re very shy animals really, and quite timid’, he recalled of the captive female. ‘It behaved just like a dog and it got very friendly. But when a stranger came near it would squark at them.’[16] At first he couldn’t get her to eat. The breakthrough came when he skinned a freshly caught wallaby, rolled the carcase up in the skin with the fur on the inside, and fed it to the tiger while it was still warm.[17] In June 1925 ‘Murray bros, Waratah’ advertised a ‘Tasmanian Tiger (female)’ in the ‘For sale’ columns of the Examiner and Mercury newspapers.[18] Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo offered £30 for it, prompting Cutter to deliver her by train. It was his only visit to Hobart. Four cruisers of the American fleet were in town, and Cutter recalled that ‘it was so crowded you could hardly move. I didn’t like it much’.[19]

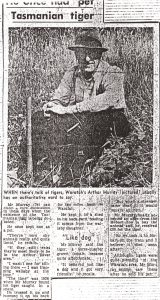

Cutter tells his story, Mercury, 13 February 1973, p.12.

The other big event in Hobart at the time was the Adamsfield osmiridium rush, which ensnared Basil Murray. In the last quarter of 1925 he pocketed £126 from osmiridium, the equivalent of a year’s wage for a farmhand.[20] Later he spent six months mining a tin show alone at the Interview River. Having set the exact date he wanted to be picked up by boat at the Pieman River heads, Basil hauled out a ton of tin ore on his back, bit by bit.[21] On another occasion he worked a little gold show on the Heazlewood River, curling the bark of gum saplings to make a flume in order to bring water to the site.[22]

It was pulpwood cutting that gave Arthur Murray his nickname. When Associated Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) started manufacturing paper at Burnie in 1938, it turned to Jack and Bern Fidler of Burnie company Forest Supplies Pty Ltd for pulpwood.[23] Over the next two decades Joe Fagan supplied about one-third of the pulpwood quota as a sub-contractor to the Fidlers. At a time when Mount Bischoff was a marginal provider for a few families, and osmiridium mining had fizzled out, Fagan became a significant employer, with about 65 men splitting barking and carting cordwood to the railway at Guildford for transport to Burnie.[24]

A good splitter would split about 3 cords of wood (a cord equals 128 cubic feet of timber) per day. Cutter held the record for the best daily effort, 8½ cords. Unlike most splitters, he never used an axe, but wedged off and split the billet into three pieces. Yet Cutter’s pulpwood stacking exasperated Joe Fagan. Unlike other men, Cutter did not stack his pulpwood as he went. Pulpwood cutters were paid according to the size of their stacks, and the large gaps in Cutter’s hasty, last-minute efforts ensured that he got paid for a bit more fresh air than he was entitled to. Kicking one such stack, Joe growled:

‘I don’t mind the rabbits goin’ through, Arthur, but I bloody well hate those bloody greyhounds behind them goin’ through the holes’.[25]

World War Two was a lucrative time for snarers. £15,000-worth of skins were auctioned at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, while more than 32,000 skins were offered there in the following year. Record prices were paid at what was probably the last annual Guildford sale in 1946.[26] Taking advantage of high demand, the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue. One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins as its seasonal haul.[27]

Both Murrays cashed in. Cutter made £600 one season.[28] Working with Eric Saddington at the Racecourse, Surrey Hills, Basil took 3000 wallabies in 1943. Unfortunately their wallaby snares also landed 42 out-of-season brush possums (21 grey and 21 black)—which landed the pair in court on unlawful possession charges. Both men were fined.[29] Basil had a reputation for being a ‘poacher’, and one story of his cunning, apocryphal or not, rivals those told about fellow poacher Bert Nichols.[30]

According to Ted Crisp, Basil was sitting at the bar at the Guildford Junction Railway Station when two Fauna Board rangers came in on the train and announced they were looking for Basil Murray, whom they believed had a stash of out-of-season skins. Then they set off for his hut, rejoining the train to go further down the line:

‘Old Baz headed down by foot and took after them, he was a pretty good mover in the bush and the trains weren’t real fast … and by the time he got down there, they’d found his skins, decided there were too many to carry out so they’d hide them and pick them up at a later date, and of course old Baz was sitting there watching them, they had to catch the train back a couple of hours later, they left and old Baz picked up the skins and moved them to another place …’

By the time the Fauna Board rangers got back to Guildford, Basil was still in the bar, propped up against the counter.[31] However, the taxman did better than the Fauna Board rangers. Basil seems to have been a chronic tax avoider. He and Eric Saddington were camped at Bulgobac, squaring sleepers and snaring, when they were busted for not filing tax returns for the years 1941–42–43.[32]

Basil kept on in the same vein, landing a £25 fine for not lodging a 1943–44 return and then a whopping £60 for the 1947–48–49 period.[33] Things finally got too hot for Basil, who adjourned to the Victorian goldfields for a time.[34]

In 1951 Basil was the cook for the party re-establishing the track between Corinna and Zeehan. One of the track-makers, Basil’s nephew Barry Murray remembered him as ‘a good old cook, as clean as Cutter was rough. They were just opposites. He had a big Huon pine table. He used to scrub it with sandsoap every day, and he would have worn it away if he’d stopped there for two or three years’.[35] Basil became well known as APPM’s gatekeeper at the Hampshire Hills.

In 1963 Cutter Murray was one of Joe Fagan’s men recruited by Harry Fraser of Aberfoyle in a party which investigated the old Cleveland tin and tungsten mine and recut the Yellowband Plain track to Mount Lindsay. At the party’s Mount Lindsay camp Cutter used snares to reduce the numbers of marauding devils that were tearing through the canvas tents, biting the tops off sauce bottles and biting open tins of beef and jam.[36]

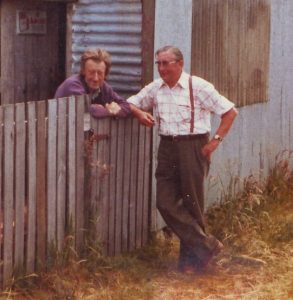

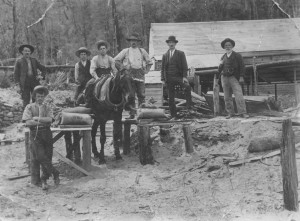

Cutter Murray (left) and friend at Waratah. Note the Ascot cigarettes advertisement on the wall behind him. Photo courtesy of Young Joe Fagan.

Cutter snared until virtually the day he died in the 1980s, making him—along with Basil Steers—one of the last of the snarers. He possumed on North’s block and took wallabies on the Don Hill, under Mount Bischoff, wheeling the skins home draped over a bicycle. A great snaring dog, a labrador that he had trained to corner but not kill escaped game, made his life easier.[37] Nothing is known to remain of his hunting regime, not a hut or a skin shed. Barely a photo remains of the hardy bushman. His tiger tale flitted across the country via newspaper in 1984, then was forgotten.

Unfortunately Cutter Murray’s travelling tiger has an equally obscure legacy, apparently dying soon after it was received at the Beaumaris Zoo.[38]

[1] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[2] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[3] Registration no.484, born 16 May 1898, RGD33/1/85 (TAHO). Basil Murray’s years of birth and dirt are recorded on his headstone in the Wivenhoe General Cemetery, Burnie.

[4] ‘Ridgley’, North West Post, 8 October 1907, p.2.

[5] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’, Australian, 1984, publication details unknown.

[6] Basil and John Murray were refused an exemption (‘Waratah Exemption Court’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 November 1916, p.2; ‘Burnie: in freedom’s cause’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 13 January 1916, p.2), but there is no record of Basil serving.

[7] ‘Tasmanian casualties’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 22 September 1916, p.3.

[8] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[9] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[10] Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[11] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[12] Cutter Murray and Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[13] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, the author, Somerset, 1994, pp.62–66.

[14] Cutter Murray and Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[15] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’, Australian, 1984, publication details unknown.

[16] Cutter Murray; quoted in ‘He once had pet Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 13 February 1973.

[17] AAC (Bert) Mason, No two the same: an autobiographical social and mining history 1914–1992 on the life and times of a mining engineer, Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Hawthorn, Vic, 1994, p.571.

[18] See, for example, ‘For sale’, Examiner, 17 Jun 1925, p.8.

[19] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’.

[20] Register of osmiridium buyers’ return of purchases, MIN150/1/1 (TAHO).

[21] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[22] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[23] Steve Scott, quoted by Tess Lawrence, A whitebait and a bloody scone: an anecdotal history of APPM, Jezebel Press, Melbourne, 1986, p.25.

[24] Kerry Pink, ‘His heart belongs to Waratah … Joe Fagan’, Advocate, 10 August 1985, p.6.

[25] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[26] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4; ‘Over 32,000 skins offered at sale’, Advocate, 13 September 1944, p.5; ‘Record prices at Guildford skin sale’, Advocate, 30 July 1946, p.6.

[27] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4.

[28] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[29] ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[30] For Nichols’ poaching, see Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.116–19.

[31] Ted Crisp; quoted by Tess Lawrence, A whitebait and a bloody scone: an anecdotal history of APPM, p.26.

[32] ‘Men fined’, Mercury, 5 May 1944, p.6.

[33] ‘Fines imposed for income tax offences’, Mercury, 5 September 1946, p.10; ‘Fined for tax breaches’, Examiner, 6 July 1950, p.3.

[34] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[35] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[36] AAC (Bert) Mason, No two the same, pp.570–71, 577, 579.

[37] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[38] Email from Dr Stephen Sleightholme 26 December 2018; Cutter Murray stated his belief that it died soon after arrival in Hobart in ‘He once had pet Tasmanian tiger’. I thank Stephen Sleightholme and Gareth Linnard for their contributions to this story.

by Nic Haygarth | 28/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

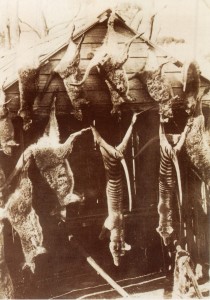

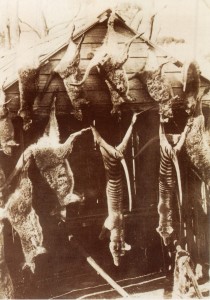

A photo of two thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) carcasses suspended from a hut in Waratah, Tasmania, has intrigued students of the animal’s demise. Who killed these tigers? Eric Guiler speculated that they might have been taken by a Waratah hunter John Cooney who collected two government thylacine bounties in 1901.[1]

In fact the photographer, Arthur Ernest Warde, was himself a hunter and future Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, and the photo probably depicts his own kills. The man in question was a wheeler and dealer who spent three decades in Tasmania, turning his hand to any useful practical skill—including photography and exploiting the fur trade. The terms of Warde’s stint at the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s (VDL Co’s) Woolnorth property in the years 1903–05 confirm that, far from being specialist thylacine killers, the so-called Woolnorth tigermen were simply regular hunter-stockmen who also took responsibility for managing snares set for thylacines at Green Point near latter-day Marrawah. Given this collision of photographer and tiger snarer, it is tantalising to wonder what tiger-related photos Warde took while working at Woolnorth that may still remain undiscovered in a family scrapbook, or which may have long since mouldered away in someone’s back shed, lost for all time.

Ernest Warde photo of Maori chiefs, 1998:P:0383, QVMAG

Warde’s early life remains as mysterious as his tiger photo. In Wellington, New Zealand in 1890 he married renowned whistler and music teacher Catherine Elizabeth Walker, née Dooley, the daughter of Zeehan shopkeeper Joseph Benjamin Dooley and his wife Annie Dooley.[2] The Wardes, both of whom were known by their middle name, appear to have been in Bendigo in 1891 and by 1893 had relocated to Inveresk, Launceston, where the photographer, ‘late of New Zealand’, presented images of Maori chiefs to the Queen Victoria Museum.[3] The couple’s first child, Winifred Warde, was born at Launceston in 1893.[4]

The Warde photo of the two thylacine carcasses, from Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian tiger: a lesson to be learnt, p.129.

In 1896 the Wardes were in Devonport, in 1897 in Waratah, where second daughter Mabel was born.[5] Elizabeth taught music in both towns.[6] It was supposedly at Waratah that Warde took the intriguing photo, which shows two thylacine and eight wallaby carcasses hanging from the front of a building more closely resembling a woodshed than a hunting hut. The photo slightly pre-dates the era of the skinshed, the unique Tasmanian invention which revolutionised high country hunting by enabling hunters to dry large numbers of skins without leaving the high country. In fact, the photo does not show drying skins, but carcasses which are yet to be skinned. What is the purpose of the image? It is not the conventional trophy photo, which would pose the hunter with his trophy kill. Warde himself collected two thylacine bounties, ten months apart, in September 1900 and July 1901, while living at Waratah, where he probably learned to hunt.[7] Just as the bushman Thomas Bather Moore celebrated in verse the incident in which one of his dogs killed a ‘striped gentleman’, perhaps for Ernest Warde the novelty of killing a thylacine or two justified commemoration or memorialisation of the event with a photo. It is likely that he killed at least one of the thylacines in the photo, and afterwards submitted it for the government bounty.

Warde’s Osborne Studio photo of the fire at ER Evans boot shop and house, Burnie.

From the Weekly Courier, 1 March 1902, p.17.

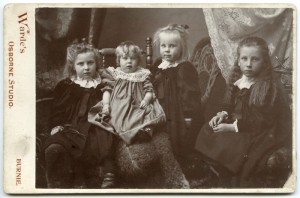

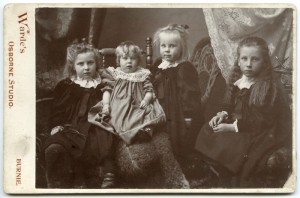

Warde’s Osborne Studio photo of EJ Wilson’s children, 1986:P:0045, QVMAG.

Warde was one of many to have practised photography in Waratah, and with the town’s population still growing, he would not be the last. However, in December 1901 a better photographic opportunity arose in a coastal centre, Burnie, when John Bishop Osborne decided to move on. Warde took over Osborne’s Burnie studio, while also operating a farm at Boat Harbour and advertising his and Elizabeth’s services as musicians.[8] In 1902, while Elizabeth was busy producing the couple’s third child, Francis Harold Warde, photos credited to Warde and to Warde’s Osborne Studio photos appeared in the Weekly Courier and Tasmanian Mail newspapers.[9]

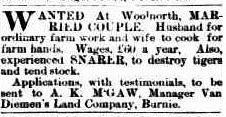

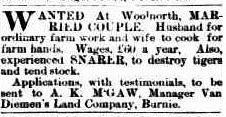

The tigerman job advertised, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 22 May 1903, p.3.

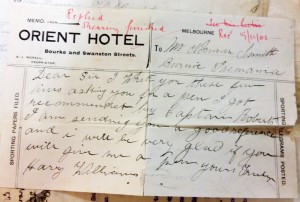

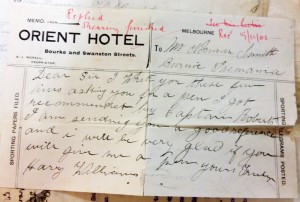

Warde appears to have made the acquaintance of VDL Co agent AK McGaw while supplying photos to the company. The photography business must not have been lucrative, as in May 1903 he agreed to replace the gaoled George Wainwright as the Mount Cameron West tigerman.[10] Warde’s contract as ‘Snarer’ shows him to be a general stockman and farm hand engaged for the Mount Cameron West run, with the killing of ‘vermin’ (that is, all marsupials) his primary duty:

‘It is hereby agreed that the Snarer shall proceed to Mount Cameron Woolnorth … and shall devote his time to the destruction of Tasmanian Tigers, Devils and other vermin and in addition thereto shall tend stock depasturing on the Mount Cameron Studland Bay, and Swan Bay runs, also effect any necessary repairs to fences and shall immediately report any serious damage to fences or any mixing of stock to the Overseer & shall assist to muster stock on any of the above runs whenever required to do so & generally to protect the Company’s interests shall also prepare meals for stockmen when engaged on the Mount Cameron Run’.

The pay was £20 plus rations (meat, flour, potatoes, sugar, tea, salt, with a cow given him for milk) with the snarer providing his own horse.[11] A butter churn was later provided, and farm manager James Norton Smith added that ‘when he wants a change he can catch plenty of crayfish’.[12] No rent was paid for the Mount Cameron West Hut, and the former company reward of £1 per thylacine still applied. In addition, the VDL Co agreed to supply the snarer ‘with hemp and copper wire for the manufacture of tiger snares only (the Snarer supplying such materials as he may require for Kangaroo or Wallaby snares)’.[13] That is, the necker snares used to catch thylacines were stronger than those used to catch wallabies and pademelons. It was the same deal as for his predecessors: the company supplied a small wage and rations, encouraging the stockman-hunter to protect his flock by killing thylacines and keep the grass down by killing other marsupials. In July 1904 Warde advertised in the newspaper for an ‘opossum dog’, which he was willing to exchange for a ‘splendid kangaroo dog’. He knew that the best money was in brush possum furs.[14]

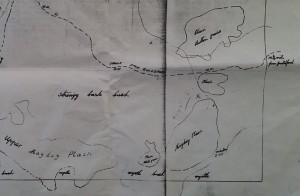

Warde was the last stockman-hunter based at Mount Cameron West. Nearing the close of 1904 he was also trying to ‘get a good line of snares down from the Welcome [?] forest into the back of the Studland bay knolls’, which would give him ‘a splendid tiger break …’[15] However, he had probably already landed the last of his twelve thylacines for the company. In February 1905 the Mount Cameron West Hut was burnt down, Warde’s family escaping the flames late at night in the breadwinner’s absence.[16] That the hut was not replaced for years confirms that the thylacine problem, real or perceived, had abated.[17]

After leaving Mount Cameron West, Ward ditched the ‘e’ from the end of his surname and complemented the Boat Harbour farm with a general store. The Wardes remained there until in 1923 they sold up their store to Hamilton Brothers of Myalla and relocated to New Zealand, where A Ernest Warde reattached his ‘e’ and reinvented himself firstly as an Otago real estate agent, working for his father-in-law, then as an Auckland used car salesman.[18] Elizabeth Warde disappeared from the picture and, appropriately, Ernest wound back his personal odometer to 49 years when in 1932 he took his new 33-year-old bride Mary Winifred Tremewan to see England and America.[19] The new marriage ended when the couple was living in Sydney in the mid-1940s.[20] Warde’s death certificate, in July 1954, described him as an ‘investor’. In truth, he was a trans-Tasman jack-of-all-trades who happened to be the last of the Woolnorth tigermen.[21]

[1] Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian Tiger: a lesson to be learnt, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, 1998, p.129. Cooney’s bounty payment was no.249, 19 June 1901 (2 adults, ’11 June’), LSD247/1/ 2 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [hereafter TAHO]).

[2] For her prowess as a whistler, see ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 15 January 1894, p.5; ‘Burston Relief Concert’, Daily Telegraph, 16 January 1894, p.3 and ‘Entertainment at the Don’, North West Post, 21 April 1894, p.4. Elizabeth Walker is the mother’s name given on the couple’s three children’s birth certificates. On the 1903 Electoral Roll her name is given as Catherine Elizabeth Warde.

[3] ‘Australian Juvenile Industrial Exhibition’, Ballarat Star, 26 May 1891, p.4; ‘The Museum’, Launceston Examiner, 23 December 1893, p.3.

[4] She was born 31 August 1893, birth registration no.606/1893, Launceston.

[5] In 1896 E Warde of West Devonport advertised to sell a camera, lens and portrait stand (advert, Mercury, 23 May 1896, p.4). In 1897 the Wardes featured in a Waratah dance (‘Plain and Fancy Dress Dance’, Launceston Examiner, 9 October 1897, p.9). Mabel Warde’s birth was registered as no. 2760/1898, Waratah.

[6] Advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 January 1902, p.3.

[7]; Bounties no.293, 18 September 1900 (’11 September’); and no.305, 12 July 1901, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[8] See advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 December 1901, p.4; ‘Table Cape’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 19 November 1901, p.2. John Bishop Osborne, the former Hobart photographer, had been on the move every few years since setting up at Zeehan in 1890. Osborne moved to Penguin, and he would end his days in Longford, where he lived 1921–34. Ernest and Elizabeth Warde advertised that they were available to supply music to parties and balls, while Elizabeth also sought piano, organ and dance students (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 January 1902, p.3).

[9] Francis Harold Warde was born at Alexander Street, Burnie, on 17 December 1902 (registration no. 2061/1903). Catherine Elizabeth Warde and Ernest Warde were listed at Burnie on the 1903 Electoral Roll.

[10] The new operator of the Osborne Studio was Mr Touzeau of Melba Studio, Melbourne (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 27 June 1903, p.1). Warde held a furniture sale at his Alexander Street, Burnie, residence in June 1903 (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 13 June 1903, p.3) and advertised for a ‘strong quiet buggy Horse and good double-seated Buggy (tray-seated preferred …’ (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 8 June 1903, p.3).

[11] For Warde’s proposed rations, see James Norton Smith to AK McGaw, 4 June 1903, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[12] James Norton Smith to AK McGaw, 4 June 1903; Ernest Warde to AK McGaw, 7 October 1903, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[13] Agreement between the VDL Co and Ernest Warde, 29 May 1903, VDL20/1/1 (TAHO).

[14] Advert, North West Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 26 July 1904, p.3.

[15] E Warde to AK McGaw, 22 December 1904, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Marrawah’, North West Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 February 1905, p.2.

[17] Woolnorth farm journal, 3 February 1905, VDL277/1/32 (TAHO).

[18] ‘Boat Harbor’, Advocate, 31 January 1923, p.4; ‘Bankruptcy’, Auckland Star, 27 September 1929, p.9.

[19] Did Elizabeth Warde die or did the couple divorce? No record of her was found. According to their marriage certificate (registration no.8401/1929), Mary Winifred Tremewan was born in New Zealand in October 1898. For their ten-month English and American holiday, see ‘The social round’, Auckland Star, 6 January 1933, p.9 and UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960. They sailed from Sydney to London on the Ormonde.

[20] Record no.1208/1944, Western Sydney Records Centre, Kingswood, NSW.

[21] Warde was not the last man to kill thylacines at Woolnorth, but the last in a long line of hunter-stockmen appointed specifically to Mount Cameron West to look after stock and manage the thylacine snares at Green Point.

by Nic Haygarth | 20/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

Ever felt the need to turn the orthodox version of history on its head, and look at it upside down? Sometimes I want to write history from the ground up, from the perspective of people at the bottom of the food chain. With that in mind, I once set out to try to prove that the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) was primarily a fur farmer during its first century, that is, that more money was generated by the culling of marsupials on its land than by grazing and agriculture. Unfortunately, there are few surviving records of the skins sales of disparate hunter-stockmen employed by the company, making the task very difficult.

That the VDL Co learned to exploit the fur trade emphasises that the company’s survival for nearly 200 years has pivoted on its flexibility. When wool-growing failed, it withdrew, leased its lands and waited for the right time to return as a wool, dairy, beef, timber and brick producer. When it could find no minerals on its lands, it built a port and established a railway so that it could exploit other people’s mineral exports. It sold its land and its timber. When the fur trade peaked in the 1920s it exploited that. Now it is referred to as Australia’s biggest dairy farmer. Is high-end heritage tourism or Chinese niche tourism the next chapter in the story of Woolnorth, the VDL Co’s remaining property?

Just to rewind a little, the hunter-stockmen who worked the VDL Co’s land had always exploited the fur trade. It was part of their employment obligations: we pay you a small wage, thus giving you the incentive to increase your income by killing all the grass-eating marsupials and all potential predators (tigers, wild dogs and eagles) of sheep, and thereby conferring a mutual benefit. You sell the marsupial skins, and we will even throw in a bounty for every predator you kill.

The killing of predators represented a bonus for hunter-stockmen whose main game was killing wallabies, pademelons and possums. By 1830 thylacines were being blamed for killing the company’s sheep, although it is clear that poor pasture selection and wild dogs were bigger problems. After the catastrophic loss of 3674 sheep at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills in the years 1831–33 to severe weather conditions and the attacks of wild animals, it was decided to temporarily cease grazing sheep there, transferring that stock to Circular Head and Woolnorth.[1] In 1830 a £1 bounty was offered for the killing of a particular thylacine at Woolnorth.[2] From 1831 the VDL Co paid a regular reward for killing thylacines on its properties, initially 8 shillings, later 10.[3] The Court of Directors in London seemed to panic about the company’s prospects, stating that ‘We fear the hyenas and wild dogs, more than climate’.[4] The dilemma of the dog problem is clear. Requests for a thylacine-killing dog for Woolnorth were matched by reports of sheep depredations of dogs belonging to Woolnorth servants.[5] In 1835–37 the VDL Co employed a dedicated ‘pest controller’, James Lucas, to kill wild dogs and thylacines at first at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, then at Woolnorth.[6] Lucas, a ticket-of-leave convict, could be said to have been the first Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, although he was never referred to by that name and was employed there only briefly.[7] He operated on the same thylacine bounty of half a guinea. Whether due to Lucas’ performance or other influences, stock losses at Woolnorth dropped dramatically during his time there and the panic over thylacines and wild dogs subsided. However, bounty payments for the killing of predators had been resumed by 1850, as the following table illustrates:

Rewards paid by the VDL Co for the killing of predators at Woolnorth 1850–51

| Name |

Time |

Program |

Kill |

Payment |

| Edward Marsh |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena |

5 shillings |

| A Walker |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Two hyenas |

10 shillings |

| Richard Molds |

Aug 1850 |

Cross bred Leicester sheep |

Three dogs |

15 shillings[8] |

| A Walker |

Nov 1850 |

Improved sheep |

Hyena |

£1-2-11[9] |

| Richard Molds |

Feb 1851 |

Leicester sheep |

Dog |

5 shillings[10] |

| A Walker |

Sep 1851 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena & Two Eagle Hawks |

4 shillings 6d[11] |

| W Procter |

Dec 1851 |

Woolnorth |

Hyenas |

10 shillings[12] |

VDL Co withdrawal and the Field brothers on the Surrey Hills

In 1852 the VDL Co withdrew from Van Diemen’s Land, becoming an absentee landlord and, by 1858, its Hampshire and Surrey Hills and Middlesex Plains blocks were all leased to the Field family graziers. Tasmanian furs were already renowned, even before a market was found for them in London. Tasmanian bushmen and excursionists favoured possum-skin rugs as bedding. The best brush possum rugs to be had in Melbourne were reputedly those made by Tasmanian shepherds from snared skins, where the animals grew larger and more handsome than their Victorian counterparts.[13]

Fields’ outposted hunter-stockmen invariably hunted for meat, skins and clothing, burning off the surrounding scrub and grasslands to attract game. When an 1871 party visited the Hampshire Hills station, the peg-legged Jemmy, who was the designated cook, whipped up wallaby steaks. At the Surrey Hills, Charlie Drury, a delusional ex-convict hunter-stockman whom Fields inherited from the VDL Co, fed them cold beef, and the visitors got to try those famous possum-skin rugs, which, as was customary, were alive with fleas. While his guests battled these, Drury went ‘badger’ (wombat) hunting by the light of the moon with about a dozen kangaroo-dogs, bringing home three skins and one entire animal—presumably for breakfast. As he explained at the dining table, ‘the morning after I have been out badger-hunting at night I always eat two pounds of meat for breakfast, to make up for the waste created by want of sleep’. Travelling further, the party found that Jack Francis, stockman at Middlesex Plains, made his family’s boots and shoes from tanned hides. He also tanned brush possum skins for rugs, which again formed the bedding—flealessly this time.[14]

Records of hunter-stockman sales of skins from this period are scant. A rare example is an account in the VDL Co papers of its Mount Cameron West ‘tigerman’ William Forward sending 180 wallaby and 84 pademelon skins to market in April 1879.[15] In 1879 the open season for ‘kangaroo’ (wallaby) was from 31 January to 31 July, suggesting that Forward’s haul represented at most two months’ worth out of a six-month season.[16] By market prices of the time these skins would have been worth at least £8–4–0 and at most £14–14–0. If we assume that his haul for the six-month season was three times as much, we can imagine him earning at least as much as his annual wage of £20–£30. And that is without bonuses for thylacine killings.

Luke Etchell, career bushman

While Charlie Drury was drinking himself to death at his hunting hut on Knole Plain, and the VDL Co plotting the removal of Fields and all their wild cattle from the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, Luke Etchell was a child growing up fast. He was the son of John Etchell or Etchels, a transported ex-convict harking from rural Lancashire. How many of the sins of the father were visited on the son? By the time of his transportation at the age of fifteen, John Etchell had already racked up convictions for housebreaking, theft, assault and, perhaps most telling of all, vagrancy. He was illiterate.[17] While still a convict in Van Diemen’s Land, he twice saved someone from drowning. [18] However, the negative side of the ledger kept him in the convict system. Christopher Matthew Mark Luke Etchell—a child with most of the Gospels and more—was born to John and Mary Ann Etchell, née Galvin, at Stanley, on 17 December 1868, as perhaps their fourth child.[19] (The origins of Mary Ann Galvin or Galvan have so far proven elusive.[20]) His family lived in a hut at Brickmakers Bay which was destroyed by fire in 1874, then appears to have moved to Black River, at a time when payable tin had been found at Mount Bischoff and specks of gold in west- and north-flowing rivers.[21] John Etchell worked as a labourer, a paling splitter and a prospector who claimed to have found gold eighteen km south-east of Circular Head in 1878.[22]

Life was not harmonious or easy, however, as suggested by Mary Ann Etchell’s successful application for a protection order against her husband in August 1880. In the court proceedings she alleged that about a year earlier he had threatened to sell everything in order to raise money to get him to Melbourne, where she supposed he was now. For the last five months all he had contributed for the upkeep of his family was 228 lb (103 kg) of flour and one bag of potatoes. [23] It seems that the family never saw John Etchell again and, given the request for a protection order, they were probably glad about it.

Certainly Luke Etchell became self-reliant very quickly. He claimed that at the age of nine, that is, in 1877, he was already working in a tin mine on Mount Bischoff and at one of the stamper batteries at the Waratah Falls, and it is true that, almost in the Cornish tradition, young boys found mining work of this kind.[24] (One of his contemporaries as a bushman, William Aylett, born in 1863, claimed to have been learning how to dress tin at Bischoff at the age of thirteen in 1876.[25]) His English-born relative John Wesley Etchell was certainly established in Waratah by December 1878, operating a shop owned by the ubiquitous west coaster JJ Gaffney, and the family made the move there, presumably with John Wesley Etchell as the major breadwinner. [26] Luke, like some of his brothers and sisters, had at least one brush with the law in his youth.[27]

Even ‘Black’ Harry Williams the tiger killer needed to go shearing for additional income. Here he asks the VLD Co for a shearing pen in 1901. From VDL22-1-31 (TAHO).

Etchell was probably with his family at Waratah until at least 1886, when he was eighteen. Over the next two decades he became an expert bushman, apparently commanding familiarity with all the country between the lower Pieman River and Cradle Mountain.[28] His base was at Guildford Junction, the village centred on the junction of the VDL Co’s lines to Waratah and Zeehan, on the hunting territory of the Surrey Hills. He also became handy with his fists, featuring in a public boxing match in 1902.[29] Other hunters, successors to Drury, were working the Surrey and Hampshire Hills. By 1900 ‘Black’ Harry Williams, for example, the ‘colored [sic] king of the forest’, was building a reputation as a tiger tamer on the Hampshire Hills, even showing a live one in Burnie which he intended to sell to Wirth’s Circus.[30] Williams probably collected four government thylacine bounties, whereas Etchell collected only one, in 1903, most of his incidental tiger kills coming after the bounty was abolished.[31]

In 1910 ‘Tasmanian Chinchilla (clear blue Australian possum)’ took its place in the American fur catalogue alongside Hudson seal, skunk, beaver, wolf and chamois. Advert from the Chicago Daily Tribune, 17 December 1910, p.26

By 1905 Etchell was sufficiently well known as a bushman of the high country to be recommended as the man to lead a search for Bert Hanson, the seventeen-year-old lost in a blizzard on the eastern side of Dove Lake.[32] Making a living as a bushman meant grasping every opportunity that came along, be it splitting palings, cutting railway sleepers, taking a contract to build or repair a road or working an osmiridium claim. In 1910, for example, Etchell’s £30 tender for work on the road at Bunkers Hill was accepted by the Waratah Council.[33] In 1912 he obtained a tanner’s licence, suggesting that he intended to deal in skins.[34]

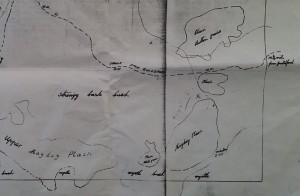

‘X’ marks the spot. The Etchell Mayday (First of May) Plain hut raided by police in 1937 in the south-western corner of the Surrey Hills block. Note also the prospectors’ camp marked nearby. From AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

However, it was as a snarer that Etchell made his reputation. He would have learned how to hunt as a boy from his father or brothers. Like the Ayletts, the Etchell family dealt extensively in the fur trade. Luke’s brother William snared and bought skins.[35] His cousin Harold Reuben Etchell had run-ins with the law over skin dealings, being the subject of a police stake-out and raid on a hut on the Mayday Plain (now First of May Plain).[36] Ernest James Etchell was another hunter who tested or blurred the hunting regulations.[37] However, Luke struck up a partnership with his brother Thomas, who also dabbled in prospecting.[38]

Atkinson’s hut and skin shed at Thompsons Park, on the Surrey Hills block. Thompsons Park was the site of a Field brothers’ stock hut. Later it also served seasonal hunters.

The pile of rubble or huge chimney butt beside Atkinson’s hut from a previous building on the Thompsons Park site.

As outlined previously, having hunters remove the plentiful game from its remaining land benefited the VDL Co stock—and the company gained doubly by charging these men for the privilege. The VDL Co engaged Surrey Hills hunters on a royalty system of one-sixth of their skins taken. In February 1912, for example, its Guildford man Edward Brown told its Tasmanian agent AK McGaw that Thomas Etchell had requested a run near the Fossey River, whereas R Brown wanted the 31 Mile or the West Down Plain (which turned out to be outside the Surrey Hills boundary). ‘I have told them that they must report to me before sending any of their skins away’, he wrote, ‘so I can count them and retain two out of every dozen for the company …’ [39] The disadvantage of this system for the VDL Co was that hunters could cheat, and later that season Brown claimed that DC Atkinson and Luke Etchell were not submitting all their skins to him from a lease Atkinson had taken on ‘the Park’. Brown found particular fault with their second load of skins:

‘The next lot was over 1½ cwt and Etchell gave me 11 which weighed 8 lbs and said “that was his share” but Atkinson would not give any as he caught them on his own ground. I know for sure he as [sic] snares set other than on his own ground. I think he was given the right on the conditions he gave 2 in the dozen regardless of where they were caught. Anyhow Atkinson should have given 11 and that would leave about ½ cwt to come off his own ground …’[40]

Ironically, the Animals and Birds Protection Act (1919) ushered in perhaps the greatest marsupial slaughter in Tasmanian history. In the open season winters from 1923 to 1928 about 4.5 million ringtail possum, brush possum wallaby and pademelon skins were registered.[41] It is easy to imagine why at some stage the VDL Co increased its royalty on the Surrey Hills from one-sixth of all skins taken to one-third. It sent men with pack-horses around the leased runs every fortnight to collect skins. Harry Reginald Paine described a raid by police and VDL Co officers on a Waratah house owned by Joe Fagan which the company believed contained skins obtained without royalty payment from the Surrey Hills block.[42] However, the late 1920s and early 1930s were dark days economically, with only the 1931 gold price spike and government incentives like the Aid to Mining Act (1927) giving hope to rural workers. Many prospectors went looking for gold in the Great Depression years, and some got into trouble. In 1932 Luke Etchell and Cummings of Guildford sought and found the Waratah prospector WA Betts, after he was lost in the snow for two weeks. After giving him a good feed, they returned him to Guildford on horseback.[43] Again, Etchell was the man to whom people looked when someone went missing in the high country.

The fashionable British bride would not think of departing on her honeymoon without her Tasmanian brush possum collar coat in 1932. Advert from the Grantham Journal, 29 October 1932, p.4.

The open season of 1934, in which nearly a million-and-a-half ringtails were taken in Tasmania, was a godsend to the VDL Co which, during an unprofitable year for farming, made £500 out of hunting.[44] Thomas Etchell may not have been too wide of the mark when it predicted that an open season would benefit the community to the extent of £300,000–£400,000.[45] Did it benefit the possum population? The downside of that record-breaking season for hunters was that it was followed by two closed seasons while ringtail numbers recovered.

By the mid-1930s Luke Etchell was stockman for the shorthorn herds of RC Field’s Western Highlands Pty Ltd, which existed at least 1932‒38, and a regular correspondent with the police on hunting matters.[46] Ahead of the open season in 1937, for example, he advised Waratah’s Constable MY Donovan that ‘the Kangaroo and Wallaby were that numerous that they were eating the grass off and leaving the sheep and cattle on the runs short’.[47] Later that year, with the thylacine finally part protected and the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board keen to find living ones, Etchell was the ‘go to man’ for the Surrey Hills, Middlesex Plains, Vale of Belvoir and the upper Pieman. He suggested the hut in the Vale of Belvoir as a good base for the search.[48] He told Summers that ‘some years ago he has caught six or seven Native Tigers during a hunting season but for many years now he has not seen or caught any, proving that they have become extinct in this part, or driven further back’.[49]

Hut in the Vale of Belvoir. AW Lord photo from the Weekly Courier, 20 July 1922, p.22.

Benefiting from Etchell’s advice, and using Thompsons Park on the Surrey Hills block as another base, the government party, consisting of Sergeant MA Summers, Trooper Higgs, Roy Marthick from Circular Head and Dave Wilson, the VDL Co’s manager at Ridgley, scoured the region near Mount Tor, around the head waters of the Leven, the Vale of Belvoir and the Vale River down to its junction with the Fury and the Devils Ravine without finding signs of thylacine activity. A further search was conducted around the Pieman River goldfield and the coast north-west of there.[50] After commenting on the large numbers of brush possums in the area searched, Summers arranged for Etchell to secure seven pairs of black possums for the Healesville Sanctuary, Victoria.[51] Again, in 1941, Etchell advised that on the Surrey Hills, ‘the kangaroo and wallaby are plentiful … and that open season would be beneficial for everyone.[52]

There were bumper hunting seasons near the end of World War II and after it, with £15,000-worth of skins sold at the sale at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, more than 32,000 skins offered there in 1944 and record prices being paid at Guildford in 1946.[53] One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins for sale in 1943.[54] Taking advantage of high demand, in 1943 the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue—these included Painter Run (Painter Plain), Park Run (Old Park?), Mayday Run (Mayday Plain, now First of May Plain, in the furthest south-east corner of the Surrey Hills block), Talbots Run (presumably near Talbots Lagoon), Peak Run (Peak Plain), Black Marsh Run (probably near the site of the old Burghley Station), and those which probably corresponded to the mileposts on the Emu Bay Railway, the 25 Mile, 36 Mile and 46 Mile Runs. Like the traditional Cornish ‘tribute’ mining system, by which parties of men competed to work particular sections of a mine, the highest bid won the contract for each run. Men paying as much as £70 for seasonal rental of a run felt short-changed when heavy snowfalls curtailed their activities, which were still subject to the official hunting season. Nearly all the men who hunted the Surrey Hills block in 1943 combined this work with pulp wood cutting for Australian Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) at Burnie, or another job in the timber industry. Waratah’s Trooper Billing estimated that pulp wood cutting averaged seven hours per day, compared to 16 hours per day for snaring.[55] Billing regarded the Surrey Hills block as a game-breeding ground which damaged the interests of adjacent landholders.[56]

Luke Etchell posing before the Guildford skin sale in 1946. Winter photo from the Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

These bumper seasons were the end of the road for the Etchell brothers. Thomas Etchell died in September 1944.[57] Brother Luke was still snaring at 78 years of age in 1946, when the Burnie photographer Winter posed him in best suit, that apparently being the outfit of choice for hauling your skins on your shoulder to the Guildford sale.[58] Luke Etchell died in Hobart on 8 June 1948.[59] There were a few good hunting season after that, but in 1953 new regulations curbed an industry already reduced by weakening European and North American demand for skins. The era of the hunter-stockman and the professional bushman—the man who could live by his nous in the bush—was drawing to a close.

[1] ‘Van Diemen’s Land Company’, Hobart Town Courier, 25 September 1835, p.4.

[2] Edward Curr to Joseph Fossey, Woolnorth manager, 12 May 1830, VDL23/3 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [henceforth TAHO]).

[3] Edward Curr to James Reeves, Woolnorth manager, 2 April 1831, VDL23/4 (TAHO).

[4] Court of Directors to JH Hutchinson, Inward Despatch no.98, 10 October 1833, VDL193/3 (TAHO).

[5] See Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 8 February 1836, 30 June 1836, 10 August 1836, 14 September 1836 and 1 February 1837, VDL23/7 (TAHO).

[6] Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 6 March 1835, VDL23/6 (TAHO).

[7] For an overview of James Lucas’ work for the VDL Co, see Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000.

[8] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[9] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[10] VDL232/1/5, p.215 (TAHO).

[11] VDL232/1/5, p.255 (TAHO).

[12] VDL232/1/5, p.272 (TAHO).

[13] HW Wheelwright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[14] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

[15] James Wilson to James Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Notices to correspondents’, Launceston Examiner, 26 November 1879, p. 2; ‘Kangaroo hunting’, Cornwall Chronicle, 31 January 1879, p. 2.

[17] John Etchell was tried at the Derby Assizes 15 May 1843 for housebreaking, stealing money and assault, see CON33/1/53. http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-53,308,90,F,60 accessed 18 December 2016.

[18] Matthias Gaunt, ‘Indulgence’, Launceston Examiner, 1 December 1849, p.4.

[19] Birth registration 702/1869, Horton.

[20] Luke’s mother, Mary Ann Etchell, died at Waratah in 1903 (‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 October 1903, p.2).

[21] See file (SC195-1-57-7410, p.1) at https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=john&qu=etchell# accessed 18 December 2016.

[22] ‘Mining intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 28 September 1878, p.2. See also Charles Sprent’s dismissal of John Etchell’s alleged tin discovery at Brickmakers Bay in 1873 (Charles Sprent to James Norton Smith, 6 July 1873, VDL22/1/4 [TAHO]).

[23] ‘Stanley’, Mercury, 12 August 1880, p.3.

[24] ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.

[25] See Nic Haygarth, ‘William Aylett: career bushman’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.28–55.

[26] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 26 February 1880, p.4.

[27] Luke and Flora Etchell were convicted of stealing potatoes at Black River in 1883 (‘Emu Bay’, Reports of Crime, 20 April 1883, p.61; ‘Miscellaneous information’, Reports of Crime, 4 May 1883, p.70). Luke’s sister Sarah Ann was convicted of concealing the birth of a still-born child in pathetic circumstances in Waratah (‘Supreme Court’, Daily Telegraph, 22 August 1884, p.3). The most serious matter was his brother Thomas Etchell’s conviction of indecent assault in Waratah (‘Supreme Court, Launceston’, Mercury, 19 February 1896, p.3).

[28] ‘The Corinna fatality’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 November 1900, p.4.

[29] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 July 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 November 1900, p.2; ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 August 1905, p.2. In December 1900 Williams exhibited the skin of a tiger said to be seven feet long in Burnie (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 December 1900, p.2). For another Williams tiger story, see ‘Inland wires’, Examiner, 14 December 1900, p.7.

[31] Potential Williams bounties: no.344, 17 November 1899 (’10 October’); no.1078, 11 September 1902 (’31 July 1902’); no.1280, 2 December 1902; no.76, 20 February 1903 (’14 February 1903’), (’17 March 1902’). Etchell bounty: 25 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[32] J North, ‘A Waratah man’s opinion’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[33] ‘Local government: Waratah’, Daily Telegraph, 9 March 1910, p.7.

[34] ‘Tanner’s licences’, Police Gazette, 9 August 1912, p.183.

[35] For snaring see, for example, Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 16 July 1911, VDL22/1/47 (TAHO). For buying see for example, ‘Alleged illegal buying of skins’, Advocate, 27 July 1939, p.2.

[36] For the police raid, see Sergeant Butler to Superintendent Grant, 10 May 1937, AA612/1/12 (TAHO). See also ‘Trappers defrauded’, Mercury, 3 September 1930, p.9; and ‘Conspiracy charge’, Mercury, 4 September 1930, p.10. In 1943 police interviewed Harold Reuben Etchell in Wynyard but failed to find any illegally obtained skins (Detective Sergeant Gibbons to Superintendent Hill, 14 September 1943, AA612/1/12 [TAHO]).

[37] ‘Sheffield’, Advocate, 21 September 1937, p.6.

[38] See HS Allen to AK McGaw, 25 October 1907, VDL22/1/39 (TAHO). Thomas Etchell went osmiridium mining in 1919 during the peak period on the western field (see Pollard to the Attorney-General’s Department, 19 November 1919, p.113, HB Selby & Co file 64–2–20 [Noel Butlin Archive, Canberra]).

[39] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 20 February 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[40] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 27 June 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[41] Police Department, Report for 1925–26 to 1927–28, Parliamentary paper 41/1928, Appendix J, p.13.

[42] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, the author, Somerset, Tas, 1992, pp.47–48.

[43] ‘Owes his life to dog’, Advocate, 13 July 1932, p.8; ‘Lost in snow for fortnight’, Advocate, 27 June 1932, p.4.

[44] VDL Co annual report 1934, Miscellaneous Printed Matter 1880‒1967, VDL334/1/1 (TAHO).

[45] T Etchells [sic], ‘Open season for game’, Examiner, 5 May 1934, p.11.

[46] ‘Personalities at the show’, Examiner, 7 October 1936, p.6. Ironically, one of his tasks now was to keep other hunters off the company’s land (see, for example, advert, Advocate, 18 January 1834, p.7) in case they endangered stock or let stock out through an open gate.

[47] MY Donovan to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, 12 January 1937, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[48] MA Summers’ report, 3 April 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[49] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[50] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[51] ‘Opossums for Melbourne’, Advocate, 26 May 1938, p.6.

[52] Luke Etchell, ‘The game season’, Advocate, 15 May 1941, p.5.

[53] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4; ‘Over 32,000 skins offered at sale’, Advocate, 13 September 1944, p.5; ‘Record prices at Guildford skin sale’, Advocate, 30 July 1946, p.6.

[54] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4.

[55] Trooper Billing to Superintendent Hill, Burnie Police, 14 August 1943, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[56] Trooper Billing to Superintendent Hill, Burnie Police, 14 August 1943, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[57] ‘Thanks’, Advocate, 26 September 1944, p.2.

[58] ‘Still trapping at 79’, Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

[59] ‘Deaths’, Advocate, 12 June 1948, p.2; ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 17/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history

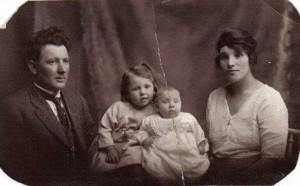

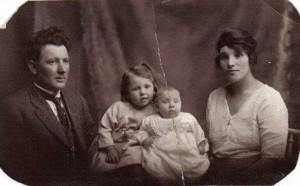

Herbert and Rosina Murray with their daughters Esma and Doreen, c1922. Courtesy of the Goddard family.

In January 1906 Herbert Villiers Murray (1892–1959) was walking from the town of Waratah to work at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, a small open cut tin mine operated by Anthony Roberts at which his brother was battery manager. Thirteen years old, he was fresh out of school. Herbert was an orphan, both his parents having died in his home state of South Australia. Since his Waratah guardian would not allow him to stay at the mine, he had no option but to tramp 8 km each day along the North Bischoff Road.[1]

Eighteen-foot-diameter water wheel and two-head battery being erected at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, North Bischoff Valley, in about 1905.

Passing the Happy Valley Face of Mount Bischoff, armed with his snake stick and crib bag, he followed the road until about 3 km further it turned into a sledge track cut for the old Phoenix battery. Rounding a spur, he saw a dog about 50 metres ahead of him, padding in the same direction. He whistled at the dog, which failed to respond as it trotted around the next spur. Herbert hurried on in his hob-nailed boots. He anticipated meeting the dog’s owner but, bafflingly, neither dog nor man came to greet him.

Are the Murray boys posed here on the pack-horse? This is another shot of the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise mine, with Cornish tin miner Anthony Roberts at right. Photo courtesy of Colin Roberts.

He reached the steep incline at the end of the metal road where the haulage was for the old Phoenix tin-dressing mill, then continued on along the sledge track, aware that the area was ‘the home and play-ground of a fair variety of snakes that travelled quite a lot in January and February—their mating period’. At last he came to the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise sawmill, and the plumber’s shop where the sluicing pipes were made. Had anyone seen a man or a dog? No. Herbert described the dog, and ‘to my surprise they told me that it was a Tasmanian tiger I was endeavouring to catch up to’.

In those days, herd of semi-wild goats roamed the valleys around Waratah and Magnet, sometimes being shot for their meat. Herbert wondered if a goat was the focus of the thylacine’s attention that day on the North Bischoff Road. He was not keen to be the tiger’s prey:

‘Fear must have obsessed me for I cut a much stouter snake-stick, also my eyes became more searching as each turn of the track or road came into view, also I heard many more bush noises when travelling to and from “The Valley”. My fear subsided as the days passed, yet the years and the ears were always on the alert.’

There were regular sightings of thylacines in the Waratah region at that time, especially along mining infrastructure in the bush: ‘A reliable prospector told me that he knew that four pups found in the decayed butt of a large fallen tree in the Savage River, had died from one shot from a gun, as they were of little or no value in those days’.[2] However, with scarcity the value of a live one grew. In 1925 the Waratah snarer Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray advertised his captured tiger for sale in the newspaper before delivering it to the zoo in Hobart.[3]

By then the Mount Bischoff mine was a marginal operation, the tin price was low and there was little work in Waratah. Herbert Murray had married English girl Rosina Goddard and moved to Melbourne, leaving the likes of his namesake, ‘Cutter’ Murray, and Luke ‘Stiffy’ Etchell, to extricate the occasional tiger—dead or alive—from their necker snares.

[1] See Goddard family research, ancestry.com,

http://person.ancestry.com.au/tree/408869/person/-2071601523/facts

accessed 17 December 2016.

[2] Herbert V Murray, 6 Renown Street, North Coburg, Victoria, to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, Hobart, 11 July 1957, AA612/1/59 (TAHO).

[3] ‘For sale’, Examiner, 15 June 1925, p.8.

by Nic Haygarth | 27/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

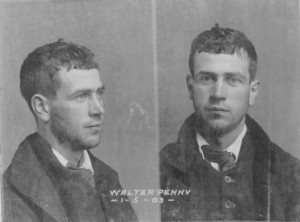

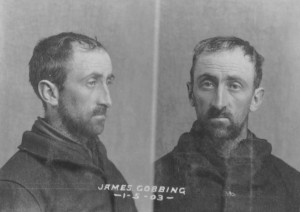

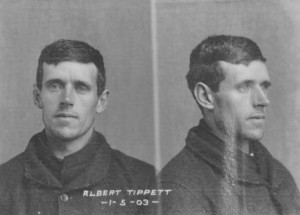

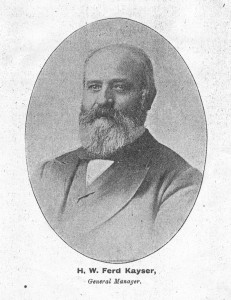

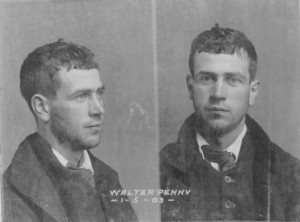

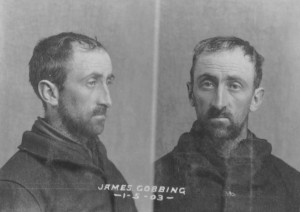

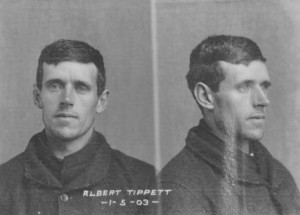

In 1903 three Waratah men—Walter Penney, James Cobbing and Albert Tippett—were gaoled for five years for receiving tin stolen from the Mount Bischoff Company. Yet the court case looked more like a showdown than a trial—the culmination of a 25-year feud between Ferd Kayser and his Cornish detractors. The three accused men worked the Waratah Alluvial plant on the Waratah River, which recovered tin lost into the water by the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds. They claimed that the tin they were accused of stealing had simply been retrieved from the bottom of the Waratah Alluvial dam on the river. The prosecution case was that the tin had been stolen directly from the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds earlier when Penney, Cobbing and Tippett worked there. At the dock, Kayser, the Mount Bischoff Co’s high profile general manager slugged it out with the canny Cornish tin dresser Richard Mitchell. Their on-going argument was ostensibly about the better ore processing method—German or Cornish. Yet in truth it was more about ego, reputation and the struggle to make a living.

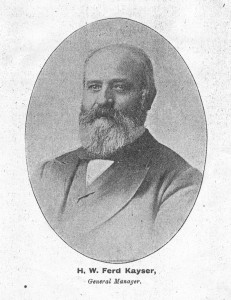

Mount Bischoff mine manager Ferd Kayser. Photo from the Australian Mining Standard, 1898.

The defence case rested on being able to show that the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds and its own tin recovery plants on the Waratah River were ineffectual, and that Mount Bischoff Co staff who had identified the stolen tin as being theirs were incapable of doing so. In speaking for the defence, Mitchell attacked Kayser’s ‘antiquated’ dressing machinery, claiming that his own plant (he was manager of the Anchor tin mine in the north-east) was ’50 years ahead of it’.[1] Laughably, Kayser failed to even identify Mount Bischoff Co dressed tin when it was placed in his hand at the dock. For five years he had been living away from the mine in Launceston as general manager, allowing John Millen to run the mine. Perhaps he was so out of touch that he had forgotten the appearance of the dressed tin he had produced for 23 years.

A succession of Cornish miners had been nipping at his heels throughout that time. Cornish miners asserted their superiority as hard-rock miners, exploiting their Cornish ethnicity as an economic strategy.[2] Being Cornish was their ‘brand’. Cornish miners were famous for their instinctive, canny style of management. They grew up mining from childhood, learning their craft on the job, without a formal mining education.[3] At Mount Bischoff Cornishmen they had tried to enhance this reputation by operating small retrieval plants, ‘lifting the crumbs from the rich man’s table’, that is, they had realised that the richest material on their leases was not lode tin or alluvial tin but escaped Mount Bischoff Co ore. The first to recognise this was the Waratah Tin Mining Company (Waratah Tin Co). Tailings from the Mount Bischoff Co sluice boxes emptied into a creek which ran through the Waratah Tin Co property into the Waratah River. In about 1878 that company’s Cornish tin dresser, Richard Mitchell, switched from working its tin lode to extracting ore from the creek.[4] Other Cornish tin dressers—ASR Osborne, William White and Anthony Roberts—followed suit. Their plants, the East Bischoff Company, Bischoff Tin Streaming Company, Bischoff Alluvial Tin Mining Company/Phoenix Alluvial Company and Waratah Alluvial Company, bore nicknames that suggested they were ‘shearing’ the Waratah River—the ‘Catch ‘em by the Wool’, ‘Shear ‘em’, ‘Shave ‘em’, ‘Hold ‘em’ and the ‘Catch ‘em by the Wool no. 2’ respectively.

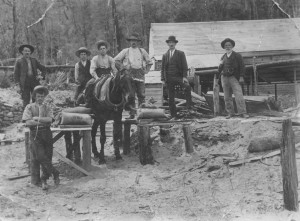

Cornish tin miner Anthony Roberts (right) operating a later tin mine, Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, in the North Bischoff Valley. Photo courtesy of Colin Roberts.

To many, Cornwall was a byword for simplicity, economy and improvisation. However, to Kayser, a champion of technology, Cornwall, the so-called ‘cradle of the Industrial Revolution’, was a ‘Luddite’. Antiquated Cornish mining methods were his favourite hobbyhorse. One of his first actions on taking over the management in 1875 was to sack the Mount Bischoff Co’s Cornish ore dresser Stephen Eddy, whose improvised appliances, he said, included ‘the hand-jigger and all the old primitive appliances his great grandfather used’.[5]

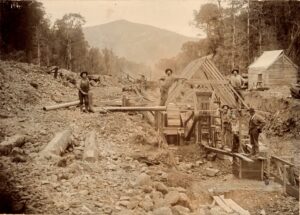

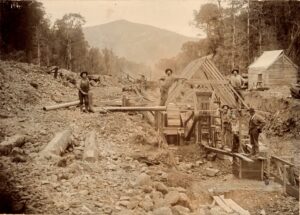

The Ringtail Sheds, in the period 1907-09, with the new power station below them at left. Stephen Hooker photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

However, Kayser could not deny that there was plenty of ore for the Cornish tin dressers to retrieve. It has been estimated that the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds alone lost 22,000 tons of metallic tin into the Arthur River system up to 1907—30,000 tons by 1928. To put that in perspective, the Mount Bischoff Co produced about 56,000 tons of metallic tin, meaning that about one-third of the tin ore mined at Mount Bischoff ended up not in smelted bars for shipment to London, but in the Arthur River system. After deriding his Cornish rivals for years, in 1883 Kayser established the first of two tin recovery plants of his own on the Waratah River. The Ringtail Sheds at the base of the Ringtail Falls on the Waratah River stood on the old Waratah Tin Co block, where Richard Mitchell had set up the very first tin recovery operation five years earlier. Well-graded access tracks to the Ringtail Sheds were constructed from both sides of the Waratah River, the track on the western side being used to pack the ore out from the sheds.[6] These formed a loop by meeting at a foot bridge across the river just above Ringtail Falls, the site of the sheds. They are still used today to visit the Mount Bischoff Co Power Station which was afterwards built below the sheds. However, so much tin remained in the Arthur River system that in the 1970s the idea was entertained of dredging not just the river but coastal deposits outside the river mouth.[7]

(The mugshots above are from GD63-1-3, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.)

[1] ‘Alleged theft of tin ore’, Daily Telegraph, 22 April 1903, p.8.

[2] Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, Cornwall Limited Editions, Fowey, Cornwall, 2004 (originally published 1996), p. 234; Ronald M James, ‘Defining the group: nineteenth-century Cornish on the North American mining frontier’, in Cornish studies: Two (ed. Philip Payton), University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 1994, cited by Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, p.234.

[3] Geoffrey Blainey, The rush that never ended: a history of Australian mining, Melbourne University Press, 1978 (first published 1963), p.244.

[4] HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, no. IV, 1892, pp.350–51.

[5] HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, p.346.

[6] ‘Alleged theft of tin ore’, Daily Telegraph, 21 April 1903, p .4.

[7] ‘Tin worth $45 million in Arthur River’, Advocate, 10 May 1973, p. 1.