Bullocks roared and rumbled through the bush. The screech of the bullockies and the whiplash of their silk crackers kept beast and burden on track as the rain poured, the bogs deepened and the rivers rose. This was how a farmer made a living—or a fortune—during the opening up of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mines. In the years 1873–77 men as far afield as Pipers River, Deloraine, Circular Head and New Ground (Harford/Sassafras) drove bullock or horse drays to Emu Bay to join locals carting tin ore from Bischoff to the wharf. And what a ‘road’ it was—a series of bullock-swallowing mires punctuated by stumps, rocks, holes, stiff climbs, creek fords and rickety river bridges. No one died on the road—mining at Bischoff was more dangerous—but taking leave of their loved ones each trip must have been a torment for the teamsters.

The first carting season in early 1873

In the early days of Mount Bischoff, when mining was confined to rooting out tin ‘nuggets’ with a pickaxe and cradling washdirt, the claim owned by Alfred Miles (AM) Walker and Ned Beecraft of Forth was a serious rival to the Mount Bischoff Co as a tin producer. Both claims needed an outlet to their market. The decision of the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) not to precipitate its tramway from Emu Bay left them at the mercy of road transport. So they formed a Mount Bischoff Road Trust to fund track improvements and hired drivers to haul in their stores and haul out their ore.

Stowport’s Cornelius Woodward drove the first bullock dray load of Mount Bischoff Co ore towards the coast on 4 January 1873. It was a taxing trip. Woodward broke his bullock dray pole in the dreaded Nine Mile Forest, and because he had to borrow tools on foot from the Surrey Hills Station, the round trip took thirteen days. Competition for carters was fierce between the rival companies. Walker and Beecraft scored the second load out of Bischoff, driven by a man named Mott, but afterwards often had the edge on the bigger company, securing the best teams at the start of the summer carting season.

Mooreville Road farmer Richard Hilder recalled a trip in January 1873, when road conditions were at their most primitive. The Hilders, Thomas senior and junior, plus Richard, drove a six-bullock team and for safety travelled with two other teams. Camps had to be chosen carefully in order to feed and water the bullocks. Day One, nine hours of travelling, got them to Ridgley, where ‘swarms’ of tiger cats (spotted quolls) attacked their stores; the second night was spent at the 31-Mile Creek; the third night at Browns Marsh, within striking distance of Bischoff. As travellers did in the vicinity of Middlesex Station, Hilder engaged in a little Gothic convict mythology when he described fording the Hellyer River near the ‘3 feet thick stone wall of what was once the VDL Co penitentiary or barracks, now fallen into decay and silence’. This was Chilton, the station abandoned by the VDL Co when it withdrew from active farming operations decades earlier. The round trip took the Hilders eight days, including a non-travelling day spent in observance of the Sabbath—a big improvement on Woodward’s experience.[1]

The difficulty of loading ore at Emu Bay

However, the road was not the only problem. There were no proper loading facilities at Emu Bay, where the 40-foot-long jetty was built without provision for a crane.[2] The port’s exposure to the weather also meant that the steamer Pioneer, which traded weekly between Launceston and Circular Head, was often unable to load passengers and cargo on either leg of its regular voyage.[3] In December 1873 the Mount Bischoff Co sent empty ore bags from Launceston to Emu Bay on the Pioneer, and engaged drays to fetch the ore, but on two consecutive trips the steamer failed to land the ore bags.[4]

Improving the road for the 1873–74 carting season

The Mount Bischoff Co prepared for the next carting season by finding a shorter route to Mount Bischoff via Bunkers Hill, and surveying a road from Bischoff out into the open country.[5] AM Walker engaged six teams, and the Mount Bischoff Co also had teams waiting for the chance to start work.[6] However, damage to the road caused by the uprooting of trees discouraged teamsters, some of whom found they could get better money hauling blackwood logs. The result was that by January 1874 the Mount Bischoff Co had only delivered a miniscule six tons of ore to the smelter in Sydney.

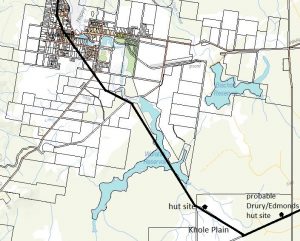

Things had to change. Mount Bischoff Co mine manager WM Crosby selected sites for a Hellyer River bridge in March 1874, while long-standing Field brothers stockmen Charlie Drury and Martin Garrett advised about crossing sites on the Wye/Wey River.[7] However, the worst part of the road was the 6.5 km between Knole Plain and the mine, including the section of it known affectionately as ‘Bog Lane’. Richard Hilder recalled that the final stage the track

‘entered a dense undergrowth of horizontal scrub through which an actual tunnel was cut with the gnarled, leafy horizontal scrub packed thickly on either side and overhead … It was so narrow that only a team in single file could pass through its 300 yards length. The bog consisted of whitish loam mixed with enormous granite boulders and tangled roots of the horizontal’.

So vile smelling was this bog in hot weather that driver and team hurried through as quickly as possible.

Hilder told the tale of an axe which disappeared in the Bog Lane mud, only to make a miraculous reappearance about ten days later after hundreds of teams had passed over it, all of them somehow escaping injury. [8]

In July 1874 the Mount Bischoff Co entered into an agreement with Charles Adams of Pipers River to cart ore, in exchange for which the Mount Bischoff Co would built stables for Adams’ horses.[9] The agreement remained essentially hypothetical until the road was rendered passable by 40 men working through the spring ahead of the official carting season in November.[10]

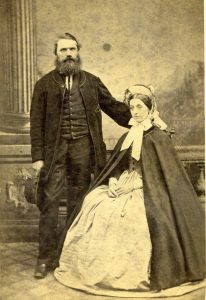

celebrating their 57th wedding anniversary. Foot & Co photo, Burnie, from the

Tasmanian Mail, 25 March 1899, p.18.

The Mount Bischoff Co fires up its Launceston Smelter

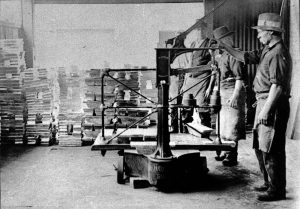

During 1874 the Mount Bischoff Co raised the first reverbatory furnace of its Launceston Smelter, ratcheting up the pressure to get a steady supply of ore from its mine. In December 1874 it appointed an Emu Bay agent to help it do so. The job of 60-year-old Northumbrian Captain James Patterson, was to arrange the dispatch of the company’s ore to the Launceston Smelter and the provision of stores and equipment to the miners.[11] Since the Emu Bay wharf was so small that two parties could not work alongside each other, Patterson had to compete with Captain William Jones, the storekeeper who doubled as agent for Walker and Beecraft.[12]

The first furnace was charged with Mount Bischoff Co ore on 4 January 1875, the event being heralded by the Cornwall Chronicle newspaper as the crowning achievement of Tasmanian industry.[13] Three days later, the furnace was charged with Walker and Beecraft ore, pointing to the smelter’s future as a custom smelter.[14]

Mounting tension between companies

Back at Emu Bay, tensions between the companies escalated when JH Munce, agent for the steamer Pioneer, apparently gave the impression that Adams was the only carter to be loaded up with stores for Mount Bischoff. Some carters took umbrage and engaged with Walker.[15] Some stated that Walker treated them better loading and unloading their wagons and giving them a feed on arrival at Mount Bischoff, services which they alleged the Mount Bischoff Co refused to do.[16] Patterson denied this was the case.[17] One of the Mount Bischoff Co directors, ED Harrop, accused Walker of bribing teamsters with an offer of £8 10 shillings, a price which Walker had only paid while the road was bad, £6 being the normal rate each way. Harrop told Walker that if necessary the Mount Bischoff Co would increase the rate to £20 to win the carters back again.[18] Walker counter-claimed that Patterson tried to seduce teamsters contracted to him by offering them £9 per ton—another charge which Patterson denied.[19]

Adams carted 100 tons of ore for the Mount Bischoff Co at £6 per ton, the directors conceding him a higher rate than originally negotiated in compensation for the tramway to the open country not having been completed, forcing Adams to load at the Waratah Falls.[20] He also carted stores up to Bischoff at £4, making his maximum potential income a staggering £1000, enough to set up a farmer for life. However, Adams found his five-horse team could move only half a ton per trip—and one trip was said to have taken him a fortnight![21] Had that been his average rate, the entire job would have taken him nearly eight years, which certainly alters the perspective on his potential fortune. The Wey and Hellyer Rivers were now bridged, but the Bischoff Road was so bad that sometimes all but the heads and backs of the horses disappeared, as if they were swimming in mud. Chinese whispers may have exaggerated reports a little, including one account related to Philosopher Smith that

‘a party going along the road had seen a hat and he took hold of it and found a man underneath with a dray and team of bullocks. I dare say by the time you receive this report in town the man will have been able to put a note in the crown of his hat just as he was sinking to say that he was there’.

Discharged cargoes and broken drays littered the roadside. In February 1875 30 teams were on the road, but Adams was far from happy with the slow progress of promised stable building at the Hampshire Hills, the Wandle River and Knole Plain. Fear for his horses’ safety in deplorable road conditions with new drivers and inadequate shelter forced him to consider withdrawal from a contract he felt the Mount Bischoff Co had already dishonoured. It was no help to Adams when in March 1875 Walker suggested that the two companies build cattle yards on VDL Co land at Browns Marsh, a proposition Norton Smith agreed to at a nominal rent.[22]

Road conditions got so bad that Patterson started paying up to £10 10s per ton, horrifying the directors. [23] Even a presiding rate of £7 failed to mollify them.[24] During the off season, Walker and Beecraft sold their Mount Bischoff claim to the Victorian-based Stanhope Tin Mining Company, and William King, Thomas Farrell, WH Atkinson and either George or William Rutherford all offered to cart for the Mount Bischoff Co for £6 per ton.[25] In the meantime, the Road Trust authorised Thomas Duncanson to spend £670 making the road useable by drays, including corduroying the Nine Mile Forest, making culverts, metalling the approaches to the Hellyer River and improving the road at the 13-Mile.[26] It was claimed that the corduroy on the long western approach to the Hellyer was being destroyed by carters who overloaded with ore in order to shut out competitors.[27]

Retribution against the King brothers

In December 1875 the King brothers were engaged at the new rate of £6, and this despite the bad road conditions. Travelling up to Mount Bischoff, two of the Kings’ bullocks ‘knocked up’ as they entered the Nine Mile Forest. The brothers shifted most of their cargo to one dray, and left the other with the two tired bullocks at the Hampshire Hills, hiding the dray with brushwood. When they returned, they found that the spokes of the dray wheels had been chopped out and the pole removed and burned, this being interpreted as punishment for ‘collaboration’ with the Mount Bischoff Co.[28]

A newspaper correspondent stated that King had six teams operating at the time, employing others to cart for him at a rate as low as £3 or £3 10 shillings per ton, while he pocketed the difference.[29] Another claimed that King engaged only two other teams at £5 per ton late in the season, gaining only a trifle from the deal.[30] Whatever the truth, many others got work at Mount Bischoff, there being 90 teams on the road during fine weather, some travelling 100 miles for the work—and most getting only £4 per ton. Some of them were turned away as the Mount Bischoff Co enforced a rule that each ore carter had to bring supplies up to Mount Bischoff. When there were no supplies to haul up, a telegram was sent to the effect that the company would now employ all carters, upon which 200 tons of tin were transported to Emu Bay in a fortnight.

The Stanhope Smelter leaves ore carting to the Mount Bischoff Co

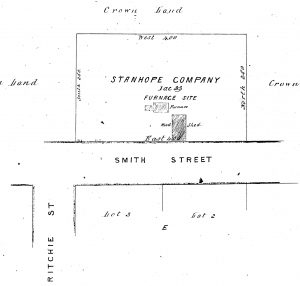

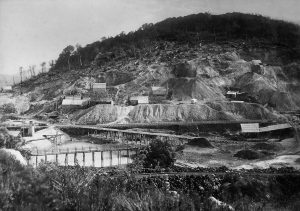

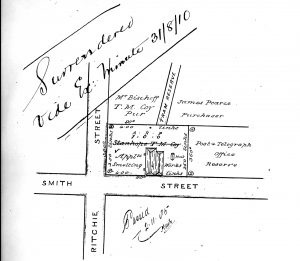

Unlike the Mount Bischoff Co, the Stanhope Co heeded German engineer Georg Ulrich’s advice to smelt at Bischoff, using wood (or at least charcoal) as fuel, engineers Nicol Turner and Scott building the first blast furnace at the corner of Ritchie and Smith Streets—right beside the early dray track to Bischoff. The outside walls of the furnace and part of the chimney were built of basalt hewn on site, while the arches of the fireplaces and the smelting hearth were constructed of firebricks packed in from Emu Bay.[31] The first firing was in January 1876, and within two months AM Walker claimed it such a success that soon it would be able to smelt 24 tons of ore per week—more than all the Bischoff mines produced together.[32]

While the Stanhope Co still needed stores and equipment delivered to Bischoff, it effectively dropped out of the ore carting business at this point, leaving the Mount Bischoff Co to feed its own smelter in Launceston. In February 1876, 66 teams were working for the Mount Bischoff Co, there having been 80 dray trips in the space of two weeks.[33] However, AM Walker, now a Waratah shopkeeper rather than a mine owner, continued his attacks on the Mount Bischoff Co, alleging that its timber falling caused an obstruction on the road.[34] He amplified this complaint in the middle of the year after his brother Henry Walker was killed by being thrown off the Mount Bischoff Co Tramway while it crossed a gully. Walker blamed the company for his brother’s death since, he believed, it blocked the road deliberately with a fallen tree so as to monopolise the traffic between Rouses Camp and Bischoff..[35]

The final carting season 1876–77

As the VDL Co’s Emu Bay and Mount Bischoff Tramway progressed, the teamsters knew their days were numbered, this being the last full season of dray carting. Relations between teamsters and the Mount Bischoff Co remained frosty, with Edwin Addison of New Ground presenting a raft of complaints against Patterson as the season opened.[36] In January 1877 the company announced it would pay £6 per ton down and £5 per ton up to Waratah, with teams being loaded at Rouses Camp in the order in which they arrived.[37]

The 1877 Rouses Camp snowball fight

However, things didn’t always go to plan. In April 1877 50 drivers and teams were stranded at Rouses Camp for days due to a shortage of ore bags. The beasts of burden were set loose to graze on Browns Marsh and the Racecourse (on the VDL Co’s Surrey Hills block) while their drivers socialised in Waratah. One day the drivers awoke to find six inches of snow on the ground around them, and with time to kill, the strong rivalry between bullock drivers and horse drivers actuated a fight—the weapons consisting of nature’s new bounty, the snow. Tom King led the bullockies, Jack Floyd the horsemen, with Fred Frampton acting as referee. The battle raged for two hours, divided into 20-minute sorties. Snowballs pounded flesh, men reeled from stinging attacks, retaliating in kind until late in the day when

‘with a “Hurrah, boys”, Captain Floyd ran up and down his lines of men, who, gallantly responding to his call, rallied and drove the bullock men inch by inch from the field and scattered them in the final decisive defeat’.[38]

All participants then dried off in front of a roaring fire, their surplus energy exhausted. New ore bags arrived from Emu Bay after midnight that night, enabling them to complete one of the last major deliveries of Mount Bischoff ore via the Bischoff Road to Burnie.

Richard Hilder’s final Bischoff dray trip was in the following month, hauling ‘fancy goods’ (clocks, watches, jewellery and drapery) up to Waratah for storekeepers the Messner brothers. The old difficulties still obtained. Hilder’s hopes of returning to Burnie with Bischoff ore were dashed when at the 29-Mile he broke an axle, forcing him to abandon his dray and transfer his load to those of his companions.[39] By late May 1877 the tramway had reached Hampshire, effectively halving the teamsters’ business, and by February 1878 not a bullock whip was to be heard cracking on the Bischoff Road.[40] By then the Mount Bischoff Co, surmounting all its problems, had kicked off the shareholder bonanza that eventually doled out more than £2.5 million in dividends.

Some notable Bischoff teamsters, with help from Richard Hilder

Charles Adams

In 1869 Launceston-born Adams (1834–1910) found gold nuggets on his Pipers River farm, after which time he invested in the Back Creek Alluvial Gold Mining Co and prospected for tin in the Georges Bay area (St Helens).[41] Adams visited Mount Bischoff in 1874, presumably as a prospector and/or potential investor, only three months before he made his offer to cart 100 tons of Mount Bischoff Co ore at £6 per ton.[42]

Thomas Addison aka ‘Grandfather Addison’

The ‘grand old man’. He could handle a bullock team ‘to perfection, and with a sonorous, commanding voice he guided his fine team through treacherous mud or over rocky road or the shocking broken corduroy. He had no strong apprehension of ever being stuck fast. We all loved Grandfather Addison’.[43]

Joseph Alexander

A number of members of the Alexander family carted Mount Bischoff ore. Joseph Alexander (c1841–1917), the son of Matthias Alexander, was born at Illawarra near Longford, but became a Table Cape farmer and later a publican and storekeeper in various centres along the north-west coast. [44]

S Andrews

He was the only teamster to drive a four-wheeled vehicle, with 10 or 12 Devon bullocks. His two pole bullocks drowned in a bog at the 27-Mile in the autumn of 1876 and had to be left there. Sam Dudfield attempted to go through the same bog in February 1877, and had to be rescued, revealing the wooden yoke, iron bow and putrid bullock remains still there in the bog.[45]

William ‘Hermit’ Applestall

Very tall and angular, supposedly seven feet tall but stooped, independent and morose, he drove a bullock team for William Henry Oldaker, bringing a young lad and dog for company. Applestall would camp with his team of ‘well-matched brindle bullocks’ away from everyone else, hence the nickname ‘Hermit’. He never overloaded his team, never hurried, never kept other teams waiting.[46]

William Atkinson

‘Roaring Billy’, farmer on the New Country Road south of Burnie who was noted for his good bullock team and skillful handling of same. Also hauled split timber and logs out of the forests along Mooreville Road and at Stowport.[47]

Jamie Blair

One of the ‘Scotch twins’ (with Jamie Dennison), who had the biggest and smallest draught horses on the Bischoff road. He had a ‘splaw-footed, raking, eagle-eyed animal that repeatedly stumbled and fell but was the pet of his master’ and would call out to the other ‘Scotch twin’: ‘Jamie, ma mon come smart, an’ help ma to git ma pet oop agin’.[48]

John Cassidy

The man presumably celebrated by the name Cassidys Marsh, an appetising spot on the old dray track somewhere between Knole Plain and Waratah. Probably John Martin/Macassin Cassidy (1853–1929) of Bengeo near Deloraine—more likely to be him than his father, the Irish ex-convict or immigrant John Cassidy (c1812–96).[49]

Billy Cunningham

Black River ventriloquist who amused bullock drivers with his impressions of farm animals in the dead of night, also a dab hand with a bullock whip.[50]

James Denison (Jamie Dennison)

One of the ‘Scotch twins’ (with Jamie Blair) who always drove together. Very fond of his horse Roly-Poly, the ‘miniature, nimble-footed chestnut gelding which no hardship of the Bischoff road could knock out’.[51]

Sam Dudfield

Samuel Dudfield (1855–1935) was born at Longford to two ex-convicts, James Dudfield, who described himself as a gardener, and Ann/Anne Orrell (aka Arwell/Orwell).[52] He farmed at St Marys Plain, Cam River (Tewkesbury), in the inner north-west. Richard Hilder described how he attempted to go through the 27-Mile bog that had drowned Andrews’ two bullocks in the autumn of 1876. It was now nearly a year later in February 1877, and Dudfield’s team had to be rescued, revealing Andrews’ wooden yoke, iron bow and putrid bullock remains still there in the bog.[53] Dudfield was reported to have shot a thylacine at St Marys Plain in 1895, which he intended to submit it for the government bounty.[54]

Thomas Farrell

Presumably Burnie hotelier and well-known prospector Thomas Farrell (c1857–1926).[55] Mount Farrell near Tullah is named after him, recalling his discovery of the White Hawk Mine, one of the early mines on the Mount Farrell field.[56] He discovered and for a time managed the King Island Scheelite Mine.[57]

Jack Floyd

Leader of the horsemen in their snowball fight against the bullock drivers at Rouses Camp in April 1877.[58]

Fred Frampton

From Ulverstone, he was referee in the Rouses Camp snowball fight in April 1877.[59]

M Gillam aka ‘Greasehorn’ Gillam

Disliked by some for the barrage of questions he asked about the origins and doings of the VDL Co while camped at their early settlements. He carried cart grease in a long Hereford bullock horn, hence the nickname ‘Greasehorn’.[60]

Harry Hills

Later a Mount Bischoff Co employee who also operated a dairy farm on Lot 6201, an old Mount Bischoff Co block at Knole Plain approximately 1880–84.[61] Hills was probably the first to stock Knole Plain with any success, John Bailey Williams having failed as a wool-grower there in the 1860s.[62] Hills had two large, fenced paddocks laid down with ‘artificial’ grass, and was supplying milk to Waratah.[63] His successor there was George Martin, who in 1891 advertised for sale the 100-acre Knole Plain dairy farm with a four-room cottage, detached kitchen, cowshed and stable.[64]

William House & ‘Red’ Stephen Margetts

A pair of bullock drivers ‘which no course speech or manners could in any way defile’. They were ‘courteous and kind in word and action, good and reliable drivers who could face without flinching the real danger of the road, bridge or river, considerate to their cattle, and good company to their companion drivers. Examples for all to follow on the Bischoff road 50 years ago’.[65]

Ike Hutchison

A horse driver from Penguin who was ‘far too old a man for the rough and tumble of a teamster on the Bischoff road’. ‘He spoke of them [his two horses] and caressed them like a real lover.’ At camp, with the billy boiled, he would wash and comb his horses’ manes, ‘at the same time speaking to them with soothing words and affectionately caressing them’. One night his horses escaped from camp, and so anxious was he to find them that he did not even stop to put on his boots, following with bare feet and rejoicing when they were found.[66]

Tom King

Leader of the bullockies in their snowball fight against the horse drivers at Rouses Camp in April 1877.[67]

William King

Launceston-born William King (c1823–1905) attended the Californian gold rushes and became a publican before settling down to farm at Table Cape and Boat Harbour during his last 40 years. Despite the incident where his wheel spokes were destroyed in 1875, Mount Bischoff ore carting apparently helped turn around his fortunes.[68]

John Martin

A bullock driver from Greens Creek (Harford). Hilder described his unusual way of yoking up his team of miniature bullocks and his cavalier attitude to braking them.[69]

Richard Mitchell

Presumably illiterate Cornish tin dresser Richard Mitchell (1852–1909), who left England in 1875, working briefly in New South Wales before arriving in Tasmania late that year. A man of that name carted tin for the Mount Bischoff Co from November 1875 until at least March 1876.[70] He later managed the East Bischoff Mine (1879–81) and the Waratah Alluvial (1881–85) at Mount Bischoff, but was better known for floating the Anchor Tin Mine Ltd in London in 1895, the deal being made controversial by the addition of the name of the premier, Sir Edward Braddon, to the company’s prospectus. Mitchell died in a London hotel room while trying to float a company to work the All Nations Mine near Moina.[71]

Harry Moles

A driver for Walker and Beecraft, he wore a white, long-sleeved moleskin waistcoat. ‘His voice had a pleasant drawl, and his speech was a rich corruption of good English. It was real fun to listen to Harry give a description or ask a question’.[72]

Charlie Radford

The VDL Co’s ‘reliable man’, who also spent years hauling celery pine and blackwood logs out of the forests at Mooreville Road and Stowport Road, and hauled logs to sawmills during construction of the VDL Co Tramway. He drove a team of fine bullocks. ‘For kindness, patience and goodwill no man could exceed Charlie … a real Christian gentleman.’[73]

Thomas Summers

A teamster who drove a team of five horses for his uncle, Thomas Summers of Mooreville Road. He had a mother and several children on the dray in February 1877 when he overturned the dray at the Wey River, but with no damage to the occupants.[74]

Ulo Wells

Bullock driver for FW Ford on the VDL Co tramway construction and probably also on ore carting.[75]

Cornelius Woodward

Woodward (1853–1943) carted the first load of ore from Mount Bischoff on 4 January 1873, completing the trip in thirteen days after breaking a bullock dray pole.[76]

[1] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Bischoff in 1873’, Advocate, 10 November 1923, pp.10–11.

[2] ‘A visit to the Mount Bischoff tin mines’, Cornwall Chronicle, 27 August 1873, p.2.

[3] ‘A trip to the tin mines’, Cornwall Chronicle, 2 December 1874 p.3.

[4] William Ritchie to James Smith, 12 December 1873, no.362, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO).

[5] James Norton Smith to James Smith, 27 November 1873; WM Crosby to James Smith, 3 December 1873, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO). The work was carried out by James Smith and Charles Sprent respectively.

[6] William Ritchie to James Smith, 17 December 1873, no.365, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO).

[7] William Ritchie to James Smith, 9 March 1874, no.65, NS234/3/1/3 (TAHO).

[8] Richard Hilder, ‘Lost and found’, Advocate, 27 June 1931, p.9.

[9] William Ritchie to James Smith, 6 July 1874, no.195, NS234/3/1/3 (TAHO).

[10] AM Walker to James Smith, 21 October 1874, no.321, NS234/3/1/3 (TAHO).

[11] ‘A pair of veteran colonists’, Tasmanian Mail, 25 March 1899, p.18.

[12] James Patterson to James Smith, 23 February 1875, no.89, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[13] ‘Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company: the first smelting’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 January 1875, p.2.

[14] EL Martin, ‘Discovery and early development, 1871–1875’, in DI Groves, EL Martin H Murchie and HK Wellington, A century of tin mining at Mount Bischoff, 1871–1971, Geological Survey Bulletin, no.54, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1972, p.33.

[15] WM Crosby to James Smith, 13 January 1875, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[16] FW Ford to James Smith, 14 January 1875, no.23, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[17] James Patterson to James Smith, 16 January 1875, no.29, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[18] AM Walker to James Smith, 14 January 1875, no.22, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[19] James Patterson to James Smith, 23 January 1875, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[20] ‘Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company’, Tasmanian, 16 January 1875, p.4.

[21] ‘Personal’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 17 August 1910, p.3.

[22] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 8 and 15 March 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[23] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 25 February 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[24] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 1 March 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[25] ‘Our tin mines’, Cornwall Chronicle, 3 September 1875, p.3; Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 9 August 1875, 1 November 1875, 15 November 1875, 22 November 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[26] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 6 September 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[27] ‘Concerning Mount Bischoff’, Launceston Examiner, 27 April 1876, p.2.

[28] ‘A dastardly act’, Tasmanian, 15 January 1876, p.12.

[29] ‘Concerning Mount Bischoff’, Launceston Examiner, 27 April 1876, p.2.

[30] ‘A Shareholder’, ‘Carting to and from Mount Bischoff’, Launceston Examiner, 23 May 1876, p.4.

[31] ‘Mount Bischoff’, Cornwall Chronicle, 13 December 1875, p.2; ‘Mining’, Launceston Examiner, 5 October 1875, p.4.

[32] AM Walker, ‘Tin smelting at Mount Bischoff’, Tasmanian, 25 March 1876, p.7.

[33] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 21 February 1876, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[34] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 24 February 1876, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[35] William Ritchie to James Smith, 24 July 1876, no.213, NS234/3/1/5 (TAHO).

[36] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 7 December 1876, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[37] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 14 December 1876, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[38] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’, Advocate, 16 October 1926, p.12.

[39] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff’: Chapter 4’, Advocate, 6 November 1926, p.26.

[40] ‘Emu Bay’, Tasmanian, 26 May 1877, p.5.

[41] Born to John and Susannah Adams on 4 October 1834, birth record no.6247/1835, registered at Launceston, RGD32/1/2 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=adams&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Births%09Births, accessed 17 October 2020; ‘Deaths’, Examiner, 15 August 1910, p.1; ‘Pipers River diggings’, Cornwall Chronicle, 11 September 1869, p.5; ‘Official notices’, Launceston Examiner, 17 February 1870, p.3; Charles Adams, ‘Discovery of tin on east coast’, Examiner, 9 May 1905, p.3.

[42] SB Emmett, ‘A trip to the tin mines at Mount Bischoff’, Launceston Examiner, 4 May 1874, p.2.

[43] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[44] ’70 years on the coast’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 18 January 1917, p.2.

[45] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: 2nd Chapter’, Advocate, 18 September 1926, p.14.

[46] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[47] Richard Hilder, ‘The real pioneers of Emu Bay: Chapter 5’, Advocate, 5 January 1935, p.9.

[48] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[49] No birth record was found for John Cassidy junior. He died 9 January 1929, supposedly aged 73 (‘Family notices’, Advocate, 10 January 1929, p.2). John Cassidy senior’s death record gives his place of birth as County Meath, Ireland. He died 16 July 1896, his age given as 84, death record no.99/1896, registered at Deloraine, RGD35/1/65 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=cassidy&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Deaths%09Deaths, accessed 10 October 2020.

[50] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Bischoff in 1873’.

[51] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[52] Born 14 January 1855, birth record no.965/1855, registered at Longford, RGD33/1/33 (TAHO),

; died 17 January 1935, will no.20614, dated 20 March 1935, AD960/1/59, p.381 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=samuel&qu=dudfield#, accessed 27 June 2019. For James Dudfield and Anne Orrell as convicts, see their application for permission to marry, 31 March 1847, CON52/1/2, p.315 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=james&qu=dudfield, accessed 27 June 2019.

[53] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: 2nd Chapter’.

[54] ‘News in brief’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 10 September 1895, p.2.

[55] ‘Mr Thomas Farrell’, Advocate, 4 June 1926, p.2.

[56] See William Innes, ‘Mining pioneers: Mt Farrell silver-lead deposits: story of discovery’, Advocate, 15 June 1926, p.7.

[57] ‘King Island: scheelite’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 9 August 1918, p.4.

[58] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[59] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[60] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[61] Richard Hilder, ‘Mount Bischoff Road experiences: Chapter 4’.

[62] John Bailey Williams to Charles H Smith, Du Croz & Co, 25 January 1865; and to VDL Co agent Charles Nichols, 11 April 1865, VDL22/1/3 (TAHO).

[63] ‘For sale’, Tasmanian, 17 March 1883, p.305.

[64] ‘For sale’, Daily Telegraph, 14 March 1891, p.6.

[65] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[66] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[67] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[68] ‘Coastal news’, Examiner, 16 June 1905, p.6; ‘The story of a pioneer’, Examiner, 21 June 1905, p.6.

[69] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: 2nd Chapter’.

[70] Minutes of meeting of directors of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 15 November 1875 and 6 March 1876, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[71] For Mitchell generally see Nic Haygarth, ‘Shearing the Waratah: “Cornish” tin recovery on the Arthur River system, Tasmania, 1878–1903’, Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.15, October 2017, pp.81–98, https://www.mininghistory.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/9.HaygarthWaratah-Final-vol.1517.compressed.pdf, accessed 10 October 2020.

[72] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[73] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[74] Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Mount Bischoff: Chapter 3’.

[75] Richard Hilder, ‘Late Mr Ulo Wells, Advocate, 16 April 1926, p.2.

[76] See Richard Hilder, ‘By road to Bischoff in 1873’.