Lasseter’s Reef wasn’t the first pot of gold to go missing.[1] Many goldfields have their holy grails, the tale of a fabled reef found but then lost, tantalising generations of prospectors. On Tasmania’s Arthur River it was the reputed reef at the Blue Peaked Hill,[2] but even ‘Australia’s biggest dairy farm’ Woolnorth, in the state’s north-western corner, wears a tale of gilded woe.

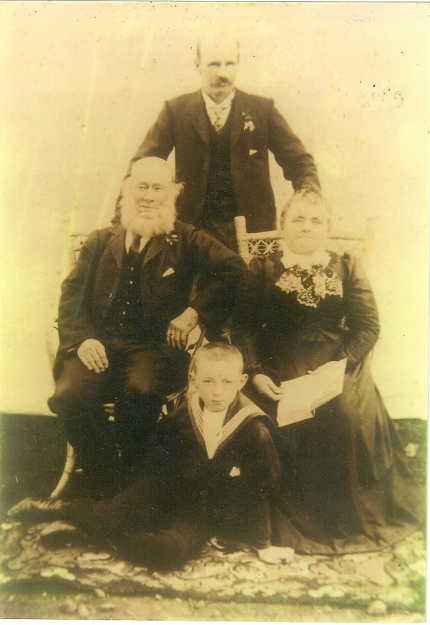

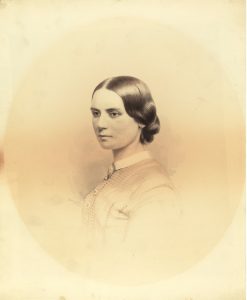

The unlikely claimant at Woolnorth was John Elmer (1801–80), who is said to have been born at Barnham, St Edmundsbury Borough, in Suffolk, England. He married Frances Kemp in that town in 1823.[3] On 22 March 1832, along with their four daughters and five other men, they arrived at Stanley on the barque Forth as indentured servants to the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co).[4]

The settlement on the coast at Woolnorth Point was then only three years old, consisting of a store, six cottages, a stable, a blacksmith’s shop and a jetty where produce could be loaded and goods landed.[5] The place was isolated, conditions primitive and rations meagre. Indentured servants were required to stay long enough to work off their passage fares, but three Forth arrivals and two other indentured servants voted with their feet by absconding in October 1832.[6] The Elmers stayed, John’s employment even surviving an incident in October 1834 when he struck Woolnorth overseer Samuel Reeves during a pay dispute.[7] A splash of gold across the drudgery of tending Saxon ewes, draining marshland, milking cows and keeping house would have been welcome.[8] However, nobody entertained ideas of a gold bounty in the years before the Californian rushes of 1848–55. Few would have known gold if they fell over it.

Shepherd at Woolnorth and Cheshunt

The Elmer family endured a decade at remote Woolnorth before taking up a Launceston butchery.[9] That move landed John Elmer in the Insolvency Court, after which he appears to have joined the wool-grower, architect and botanist William Archer IV’s Cheshunt property south-west of Deloraine.[10] Elmer would have been an interesting witness on the subject of thylacine predation on sheep, having been a shepherd at a time when few attacks were reported at either Woolnorth or Cheshunt. In 1851, when Elmer was hired or rehired as a Cheshunt shepherd and overseer at an annual salary of £40, he and Frances already had a family of six young children.[11]

James Elmer

One of their offspring was Edward James Elmer (c1835–1916), who called himself James Elmer.[12] He claimed to be ‘the oldest white born under the VDL Company’. Many seventeen-year-olds must have raced off to the goldfields at Forest Creek, Loddon River or Creswick with their fathers circa 1852 when the mosquito fleet plying Bass Strait was laden with garrulous Van Diemen’s Land diggers. No shipping records place John or James Elmer among them.[13] A tour of the Victorian goldfields would have guaranteed the Elmers a familiarity with the appearance of alluvial gold and the conditions under which it was found. But it seems they stayed home keeping sheep and saving their pennies to take up a tenant farm at Cheshunt.[14]

A deathbed confession

John Elmer died as a supposedly senile 78-year-old at Bridgenorth, West Tamar in 1880.[15] On his deathbed he told James that at Woolnorth he’d done more than keep tigers from the sheep, having found ‘plenty of gold’.[16] The question of how exactly a Suffolk shepherd could have recognised gold a decade or two before the global gold bonanza began doesn’t seem to have fazed James. Nor did his father’s prescribed senility. Then there was the matter of why John Elmer—assuming he was literate—hadn’t exploited the reef himself by, for starters, sending rock samples to an assayer or a geologist. James’ problem was that he had developed a touch of gold fever, which is exactly what happened when you hung around with that ne’er-do-well Henry Weeks.

Henry Weeks and Chummy’s gold

Native Rock farmer Weeks (1832–99) was a staunch Rechabite.[17] His weakness didn’t come in a bottle but with a geological pick: he lost his nut to mineral prospecting and mining investment. Weeks had also missed the Victorian gold rushes, only arriving in Van Diemen’s Land from Monmouth, Wales, as an assisted immigrant coalminer in 1854.[18] He must have made up for lost time. Weeks’ discovery of the rich Mount Claude (Round Hill) galena mine in 1881 distracted him from the farm but did nothing for his bank balance.[19] Chasing Chummy’s gold didn’t help much either. This Lasseter’s Reef story involved George ‘Chummy’ Webb finding a fabulous gold reef in the Forth River high country—and taking the location to the grave with him, leaving his mate Henry Weeks to rediscover it. The only surviving clue to the site, ‘with the Western Tiers behind you and Cradle in front of you’, led all comers on a merry dance.[20]

The VDL Co goes mining

Weeks wasn’t alone in taking this tack. Frustrated by poor farming returns and tantalised by rich metal discoveries just outside its property, in 1882 the VDL Co began to examine its holdings for minerals.[21] Weeks or James Elmer evidently got wind of this, and with Henry Cooper put their names to a proposal to the company. The spelling is James Elmer’s:

‘I have been told that you want some party to prospect the companys land at Woolnorth if so we wold like to take the work, as have some knowledge of the place and my Father found gold thare fifty years ago and when he was dyen he told me as near as he cold were it was. My Father was shepherd there for manney years. I was down thare some few years ago and my mates got tired before we got thare and wold not stay when we got thare so wold not stop we are astickon [sic] party now thare are three of us but only two will be abell to go at a time. If you will let me know what terms we will try and agree as we wold mutch like to go down and find the big reef for thare is plenty of gold down there. We have all had a deal of practice in mining fore gold …’[22]

No VDL Co response has been found. After decades of dealing with mostly lackadaisical prospectors, VDL Co local agent James Norton Smith probably never took Elmer’s proposal seriously. The company’s prospector, a Cornishman named James Rowe, later found nothing of value at Woolnorth or any other VDL Co property, advising it to give up prospecting.[23]

Chummy keeps his secret

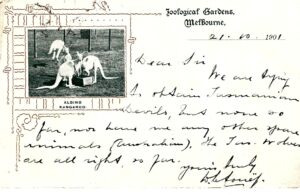

James Elmer didn’t give up. He still had the bug two decades later as a 70-year-old, repeating his father’s tale to Norton Smith’s successor Andrew Kidd McGaw:

‘I wold like to go and see if I cold find it. I wold have to drive down and cannot walk as I cold 50 years ago but am [not] a crippel yet. My horse wold do on the run aney ware so long as I got my tucker down. If I can go I will call and see you as am goen down I wold like to go soon …’[24]

This time James Elmer got there. The Woolnorth farm diary records that on 7 January 1906 Edward J Elmer and son arrived at Woolnorth to go prospecting, leaving nine days later.[25] There was no report of a gold strike.

Chummy also kept his secret. Camped near Bonds Peak in 1918 on a Chummy’s gold mission, Bill Johnson even believed he heard Henry Weeks’ ghost try to give him directions.[26] Hobart mining investor EC James was still searching for Chummy’s gold in the years 1925–30. James believed the gold may have been somewhere near Mount Emmett in today’s Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park.[27] Just as Harry Bell Lasseter’s central Australian mirage still triggers adventurers, revival of the Stormont Gold Mine in 2014 stirred the legend of Chummy’s gold.

No gold-bearing quartz reef is known to exist at Woolnorth. If John Elmer did find one, his discovery would pre-date that of John Gardiner (aka James Roberts), who claimed to have struck gold in a limestone quarry on Cabbage Tree Hill near latter-day Beaconsfield in 1847.[28] This has been cited as the first Tasmanian gold discovery. Gardiner only confirmed that it was gold he had found when he saw the precious metal later on a Victorian goldfield. Perhaps John Elmer had a similar eureka moment years down the track from his Woolnorth days, at Mangana, Mathinna, Lefroy or Beaconsfield, when the spirt was still willing but the body wasn’t up for the rigours of a gold rush.

[1] Harry Lasseter (aka Lewis Hubert Lasseter) died trying to relocate his fabled gold reef in central Australia in 1931.

[2] See Nic Haygarth, ‘SB Emmett: a pioneer Tasmanian prospector, from Bendigo to Balfour’, Circular Head Local History Journal, vol.1, no.1, 2004, pp.36–69.

[3] FHL film no.950448, sourced through Ancestry.com.au.

[4] CSO1/1/591/13412; GO1/1/13, p.517; Edward Curr to Samuel Reeves, 30 March 1832, VDL23/1/5 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA).

[5] ‘Our Own Reporter’ (Stuart Sanderson), ‘The VDL—VIII’, Advocate, 22 December 1925, p.12; Edward Curr to Samuel Reeves, 12 January and 25 September 1832, VDL23/1/4 and VDL23/1/5 respectively; Edward Curr to John Hicks Hutchinson, 11 April 1833, VDL178/1/1 (TA).

[6] Edward Curr to the Court of Directors, VDL Co, London, Outward Dispatch no,230, 15 October 1832, VDL5/1/4 (TA).

[7] John Hicks Hutchinson to Samuel Reeves, 8 November 1834, VDL23/1/6 (TA).

[8] Monthly returns Woolnorth Estate, VDL62/1/1 (TA).

[9] Paylists for Woolnorth, VDL 82/1/1 (TA).

[10] John Elmer was declared insolvent on 15 April 1844 while working as a butcher in Launceston (advert, Launceston Examiner, 17 April 1844, p.5). William Archer was the informant for the birth of Henry Thomas Elmer to John Elmer and Frances Kemp on 31 July 1844, birth record no.410/1844, registered at Launceston, RGD33/1/23 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=frances&qu=kemp&rw=24&isd=true#, accessed 1 July 2023.

[11] William Archer IV diary, 11 July 1851 (University of Tasmania Special Collections, Afterwards UTas).

[12] He was presumably the baby born in October 1835. See Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, 28 September 1835, VDL23/1/6 (TA).

[13] Another John Elmer, a free immigrant who arrived in the colony on the Water Witch, departed from Launceston for Melbourne on the brig William Hill on 27 April 1852 (POL220/1/2, p.13, TA). John E Elmer, a free arrival in the colony on the Bee, also sailed from Launceston to Melbourne on the steamer Clarence on 16 November 1852 (POL220/1/2, p.238, TA).

[14] By 1862 both John and James Elmer were tenant farmers on Cheshunt, leasing 170 and 150 acres respectively, William Archer IV diary, 15 April 1862 (UTas).

[15] Died 6 June 1880, death record no.861/1880, registered at Westbury, RGD35/1/49 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=elmer, accessed 1 July 2023; ‘Another old colonist gone’, Launceston Examiner, 9 June 1880, p.2.

[16] James Elmer, Henry Weeks and Henry Cooper to James Norton Smith, VDL Co, 12 June 1883, VDL22/1/11; James Elmer, Kimberley, to Andrew Kidd McGaw, VDL Co, 17 December 1905, VDL22/1/36 (TA).

[17] The Independent Order of Rechabites was a friendly society which encouraged abstention from alcohol. Weeks’ property Native Rock was near latter-day Railton.

[18] Descriptive list of immigrants for the Merrington. CB7/12/1/2, book 20, p.330 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=henry&qu=weeks&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Arrivals%09Arrivals+%7C%7C+Departures%09Departures, accessed 3 March 2024. Both Henry and his wife Priscilla were literate Wesleyans. Resident Mersey–Don River coalminer Zephaniah Williams applied to bring them to the colony along with other coal-mining families to work for the Mersey Coal Company.

[19] ‘Auction sales’, North Coast Standard, 17 July 1894, p.3. Bankruptcy forced Weeks to sell four properties.

[20] See, for example, ‘Lorinna’, Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1911, p.2.

[21] See Nic Haygarth, ‘Mining the Van Diemen’s Land Company holdings 1851–1899: a case of bad luck and clever adaptation’, Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.16, October 2018, pp.93–110.

[22] James Elmer, Henry Weeks and Henry Cooper to James Norton Smith, VDL Co, 12 June 1883, VDL22/1/11 (TA).

[23] James Rowe, ‘Report of Captain James Rowe’, 1886, VDL334/1/1 (TA).

[24] James Elmer, Kimberley, to Andrew Kidd McGaw, VDL Co, 17 December 1905, VDL22/1/36 (TA).

[25] VDL277/1/34 (TA).

[26] Graham Riley, Sheffield, interviewed 23 May 1993.

[27] EC James, ‘Forth Valley prospecting’, Mercury, 8 April 1925, p.12; EC James, ‘An old gold find’, Examiner, 18 December 1929, p.11; EC James, ‘Chumey’s [sic] claim’, Examiner, 4 February 1930, p.9.

[28] See for example ‘Gold in Tasmania’, Mercury, 27 March 1869, p.3.