In January 1906 Herbert Villiers Murray (1892–1959) was walking from the town of Waratah to work at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, a small open cut tin mine operated by Anthony Roberts at which his brother was battery manager. Thirteen years old, he was fresh out of school. Herbert was an orphan, both his parents having died in his home state of South Australia. Since his Waratah guardian would not allow him to stay at the mine, he had no option but to tramp 8 km each day along the North Bischoff Road.[1]

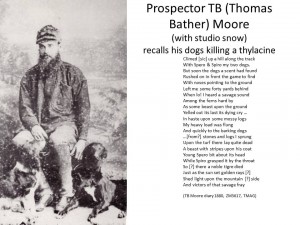

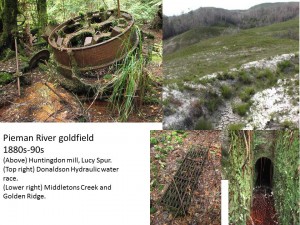

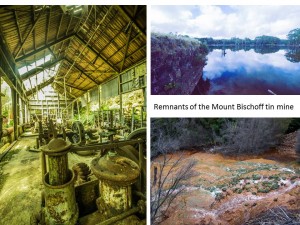

Passing the Happy Valley Face of Mount Bischoff, armed with his snake stick and crib bag, he followed the road until about 3 km further it turned into a sledge track cut for the old Phoenix battery. Rounding a spur, he saw a dog about 50 metres ahead of him, padding in the same direction. He whistled at the dog, which failed to respond as it trotted around the next spur. Herbert hurried on in his hob-nailed boots. He anticipated meeting the dog’s owner but, bafflingly, neither dog nor man came to greet him.

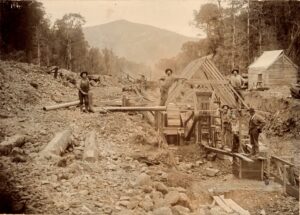

He reached the steep incline at the end of the metal road where the haulage was for the old Phoenix tin-dressing mill, then continued on along the sledge track, aware that the area was ‘the home and play-ground of a fair variety of snakes that travelled quite a lot in January and February—their mating period’. At last he came to the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise sawmill, and the plumber’s shop where the sluicing pipes were made. Had anyone seen a man or a dog? No. Herbert described the dog, and ‘to my surprise they told me that it was a Tasmanian tiger I was endeavouring to catch up to’.

In those days, herd of semi-wild goats roamed the valleys around Waratah and Magnet, sometimes being shot for their meat. Herbert wondered if a goat was the focus of the thylacine’s attention that day on the North Bischoff Road. He was not keen to be the tiger’s prey:

‘Fear must have obsessed me for I cut a much stouter snake-stick, also my eyes became more searching as each turn of the track or road came into view, also I heard many more bush noises when travelling to and from “The Valley”. My fear subsided as the days passed, yet the years and the ears were always on the alert.’

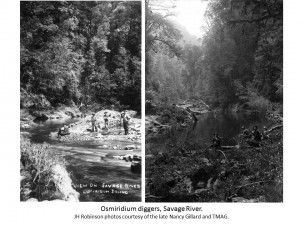

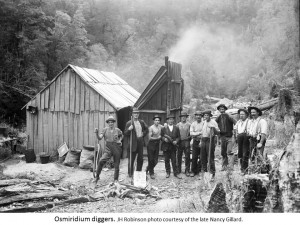

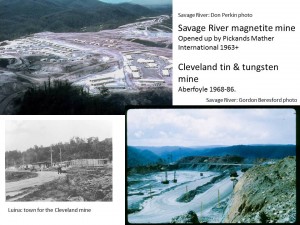

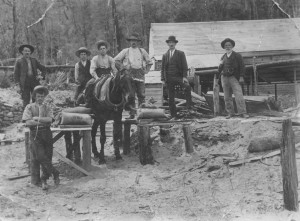

There were regular sightings of thylacines in the Waratah region at that time, especially along mining infrastructure in the bush: ‘A reliable prospector told me that he knew that four pups found in the decayed butt of a large fallen tree in the Savage River, had died from one shot from a gun, as they were of little or no value in those days’.[2] However, with scarcity the value of a live one grew. In 1925 the Waratah snarer Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray advertised his captured tiger for sale in the newspaper before delivering it to the zoo in Hobart.[3]

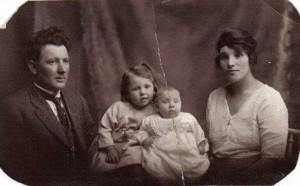

By then the Mount Bischoff mine was a marginal operation, the tin price was low and there was little work in Waratah. Herbert Murray had married English girl Rosina Goddard and moved to Melbourne, leaving the likes of his namesake, ‘Cutter’ Murray, and Luke ‘Stiffy’ Etchell, to extricate the occasional tiger—dead or alive—from their necker snares.

[1] See Goddard family research, ancestry.com,

http://person.ancestry.com.au/tree/408869/person/-2071601523/facts

accessed 17 December 2016.

[2] Herbert V Murray, 6 Renown Street, North Coburg, Victoria, to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, Hobart, 11 July 1957, AA612/1/59 (TAHO).

[3] ‘For sale’, Examiner, 15 June 1925, p.8.