A lode tin mining boom in western Tasmania followed Inspector of Mines Gustav Thureau’s poorly considered 1881 claim that ‘the Mount Heemskirk and Mount Agnew tin deposits appear to be … of grave importance to the Colony at large’ and that ‘their permanence has already been proved …’[1] As Thureau discovered, when he arrived there unwisely in winter, the difficulties of working the remote field were enormous. It was an exposed coastal area characterised by cold winters, driving rain, dense vegetation and steep terrain. There were no roads, and no useful supply routes. The closest thing to a port was Trial Harbour, a shallow inlet open to the winds which crashed the Southern Ocean onto the coast.

Tasmanians subscribed to the idea that Cornish miners were the model of practical, economical tin mining. Trained-on-the-job Cornish miners were in great demand at Heemskirk, and they encouraged their excited employers with ludicrous allusions to their homeland. In August 1881, for example, one of the Heemskirk mine managers, Robert Hope Carlisle, was said to be trying to trace the continuation of the famous Dolcoath tin lode from Cornwall across the oceans to Heemskirk.[2] However, their assertions that Tasmanian tin lodes would ‘live down’ like Cornish ones proved disastrous on a field where the deposits were actually small and inconsistent. Ironically, the fortunes of one novice Cornish miner, Josiah Thomas (JT) Rabling, in Tasmania suggest that Heemskirk was indeed the ‘Cornwall of the antipodes’, that is, it proved as hard to make a living on the Tasmanian tin fields as it was in the depressed Cornwall he had escaped.

Josiah Thomas Rabling

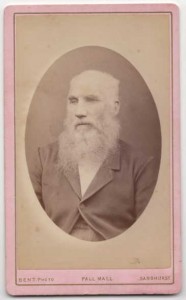

Rabling was the Cornishman chosen to work the Carn Brea Tin Mine at Heemskirk. He was born into a well-known Camborne, Cornwall mining family in about 1843, the fourth of eight children.[3] As the nephew of William Rabling senior, who had made his name and fortune in the Mexican silver mines, and also the nephew of Charles Thomas, manager of the famous Dolcoath Mine at Camborne, he was born with a mining pedigree.[4] Josiah’s father, Henry Rabling, mined in Mexico, but does not appear to have succeeded there, leaving effects to the value of less than £450 when he died in 1875.[5] The fact that Josiah Rabling was in the workforce at the age of seventeen suggests that his mining education was on the job, rather than in the class room—and there was no Camborne School of Mines until 1888. Rabling grew up at a time when England lagged behind countries like Germany and the United States of America in not having a mining academy system.[6] In 1861 young Rabling was a smith, in 1871 he was a mining clerk at Camborne, near the Great Flat Lode of tin mines and the Dolcoath Mine, which produced copper and tin for centuries.[7]

However, the crash of the copper price in the second half of the nineteenth century, the effect of the cost book system and Cornwall’s lack of a coal resource on its industrial economy, and additional failures in agriculture and fishing placed great stress on Cornish mine workers and labouring families. By 1873 the tin price was also falling, and 132 Cornish tin mines closed over the next three years.[8]

It is likely that the death of Rabling’s father in 1875 and the downturn in the local mining industry necessitated a search for work elsewhere. Competition to Cornwall from the Australian tin mines had begun with almost simultaneous discoveries on the New England tableland in northern New South Wales and at Mount Bischoff in Tasmania. Rabling arrived in Tasmania on the Argyle in 1876, perhaps being sent by British capitalists interested in Tasmanian mines.[9] During 1877 and 1878 he secured commissions to report on various mines, but by the following year was down on his luck. In August 1879, after making a little money by paling splitting, he forged a signature on a cheque which he presented in the town of Waratah (Mount Bischoff) to pay a small cartage fee incurred by a friend. He pleaded guilty to a crime committed in ‘such a childish manner’, according to a reporter for the Mercury (Hobart) newspaper, ‘with so little gain attached to it that it really looked as if he wanted to get into prison’.[10] Despite this being a first offence, Rabling was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment.[11] The effects of this experience are unknown, but one subsequent effort to make a living in Tasmania also landed him in trouble. In July 1881, along with three other men, he was tried in the Supreme Court, Hobart, on a charge of unlawfully conspiring to defraud Peter McIntyre to the tune of £400 by salting the Band of Hope Mine. Rabling and one other were found not guilty.[12]

Despite these events, such was the allure of the Cornish ‘practical miner’ that only a month later Rabling was one of two men engaged by the British Lion Prospecting Association to prospect on the Heemskirk tin field.[13] The Heemskirk tin deposits, like those of Mount Bischoff, occurred in granite—and who knew more about working tin in granite than Cornishmen?

A tributary of Granite Creek was the site of one of three Heemskirk sections leased by Rabling. The creek, he said, would be sufficient to drive machinery.[14] Even today the site, within a several hundred metres of the sea, is a remote one, three hours’ walk from shack settlements at Trial Harbour and Granville Harbour. It is hard to imagine what a young man from Camborne made of tent life exposed to the roaring surf of the Southern Ocean.

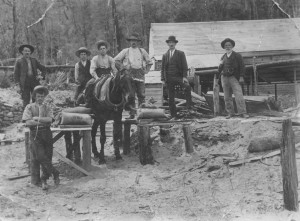

Anson Brothers photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

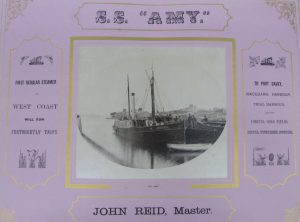

Even being delivered to the Heemskirk field was an endurance test. Rabling first ventured westward out of Launceston on the small steamer the ss Amy, which had begun to unload if not dock at Boat (later Trial) Harbour.[15] Seventeen passengers plus stores for the Pieman River goldfield were crammed aboard the tiny vessel, which took on further stores at Latrobe on the Mersey River during a five-day stopover. When the Amy got underway again, overloading had made it so unsteady that the bulk of the cargo had to be put ashore at the Mersey heads. Another layover occurred at the port of Stanley, in the far north-west, this time for bad weather. On the seventh day out of Launceston the steamer put in at the remote sheep and cattle station of Woolnorth, on the north-western tip, again delayed by buffeting winds, the passengers having enough time ashore to go rabbiting, inspect the bones of a stranded whale and hold a meeting in which they established their own west coast prospecting association! Reaching the Pieman River heads ten days out of Launceston brought good news —the dreaded bar was passable, for the first time in many days. So many vessels had come to grief on the Pieman River bar that a successful crossing was invariably met with an address of thanks to the captain and his chief officer and a hearty round of cheers. Passengers had time to develop an opinion on nearby gold workings before re-embarking for Heemskirk.[16]

Developing the Carn Brea Tin Mine

At the inaugural meeting of the Carn Brea Tin Mining Company, held in Hobart in January 1883, Rabling was appointed mine manager and promptly adjourned to the west coast with eight assistants. While publicly, at least, Rabling made no grandiose comparisons with the Cornish tin field, he did name the mine Carn Brea, after the hill that stands over his home town, Camborne, in Cornwall, perhaps a reflection of homesickness as well as an assurance of worth to cheer the shareholders. In February 1883 Carn Brea shareholders authorised a loan to pay for a battery and a 24-foot iron overshot waterwheel manufactured at WH Knight’s Phoenix Foundry in Launceston.[17] A road had to be built to North Heemskirk before the equipment was delivered by steamer at the dangerously exposed port of Trial Harbour.[18] However, when the machinery came to be hauled up the road by horse team the carters ran out of horse feed, causing further delay.[19] When visiting the Carn Brea Mine, the Mercury newspaper’s ‘special’ reporter Theophilus Jones was only able to inspect the stone cutting and wheel pit prepared for its reception, Rabling’s 84-foot drive and 20-foot winze and a lode said to be four to five feet wide. He was reassured by the manager serving him steaming Royal Blend tea, preserved meat and ‘excellent’ bread and butter. Furthermore, Rabling had

‘pitched his camp in a snug corner formed by the junction of two banks above a small creek. He has not wasted the shareholders’ money by erecting large and substantial houses, stable and blacksmith’s shops, with a store and a post office thrown into the bargain, but has contented himself with putting up tents, and cutting chimneys and fireplaces in the bank’. [20]

The most settled weather in western Tasmania is in February and March, but many water-powered mines found it too dry to operate in those months. April, May and the winter and spring months would normally provide abundant rainfall, but the west coast weather would then be bracing, to say the least. Rabling would have had no choice but to stay put and do his shareholders’ bidding by preparing the claim for crushing as soon as possible, much of his time being spent huddled in a sturdy tent.

The fatal first crushing

The first half-yearly meeting of the Carn Brea Tin Mining Company in July 1883 glowed with a happy anticipation. Neither the £1800 advance on machinery, nor the six calls on shares, had disturbed the shareholders’ equanimity. Stone assaying a payable 7.5 to 14% had been paddocked awaiting the crusher, demonstrating the admirable ‘energy and skill’ of the company’s mining manager.[21]

The Carn Brea was one of nine mines on the Heemskirk field to erect a battery during the boom period. In all, 75 or 80 head of stampers were raised.[22] By October 1883 Thomas Williams was ready to crush at the Orient tin mine.[23] The Cliff and Carn Brea were almost ready to crush, the Montagu and the Cumberland were erecting machinery and mine manager George Lightly of the West Cumberland was preparing to receive machinery.[24]

However, the failure of the Orient crushing one month later threw ‘a great damper … on lode tin mining at Mount Heemskirk …’[25] Confidence in the field evaporated. The Carn Brea Tin Mining Company kept going until at its second half-yearly meeting in March 1884 it was revealed that, although assay results from the first shipment of 30 bags of crushed ore were not yet available, directors regarded mining operations as a failure. Not surprisingly, expenditure due to work delays and heavy freight costs had far exceeded Rabling’s estimates. Work had been suspended, and many shares in the company had been forfeited. One of the directors, Grubb, condemned Rabling’s management, and several disputed that he had secured any tin from the mine. Eventually, shareholders voted to accept Rabling’s offer to take the mine on tribute (that is, working the company’s lease for a percentage of the value of ore won, so at no cost to the shareholders), the unknown value of the 30 bags of tin being taken as part payment for the wages the company owed him.[26] All work seems to have been abandoned soon after. No further substantial work appears to have taken place at the Carn Brea Mine.

Although Trial Harbour would enjoy a brief resurgence as the port for the Zeehan–Dundas silver-lead field, the Heemskirk tin field would never fulfil early expectations. Former Peripatetic Tin Mine manager Con Curtain estimated that at least £100,000 were spent at Heemskirk 1880–84 for a return of about 70 to 100 tons of dressed tin.[27] By 1962 total production on the field had not progressed substantially, amounting to a mere 668 tons of metallic tin.[28]

[1] Gustav Thureau, West coast, Legislative Council Paper 77/1882, p. 27.

[2] ‘Mt Heemskirk’, Mercury (Hobart), 5 October 1881, supplement, p. 1.

[3] Census for England 1851 and 1861.

[4] ‘Miss Eliza Rabling’, Cornishman, 19 January 1889, p. 2; Sharron P Schwartz, Mining a shared heritage: Mexico’s ‘Little Cornwall’, Cornish–Mexican Cultural Society, England, 2011, pp. 51–52.

[5] England and Wales Probate Calendar, 1858–1966.

[6] Rod Home, ‘Science as a German export to nineteenth century Australia’, Working Papers in Australian Studies, no. 104, London, 1995, pp. 7–11, 17.

[7] Census for England 1861 and 1871.

[8] Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, pp. 215–20; Allen Buckley, The story of mining in Cornwall, p. 140.

[9] ‘Gold news’, Launceston Examiner, 3 March 1877, p. 5.

[10] ‘Our Launceston letter’, Mercury, 4 October 1879, p. 3.

[11] Conduct record, CON37/1/11, p. 6063 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart [hereafter TAHO]).

[12] ‘Second Court’, Mercury, 28 July 1881, p. 3.

[13] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 30 August 1881, p. 3; ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 31 August 1881, p. 3.

[14] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 27 April 1882, p. 3.

[15] ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 31 August 1881, p. 3.

[16] ‘The west coast goldfields’, Mercury, 17 September 1881, p. 2.

[17] ‘Heemskirk’, Mercury, 23 October 1883, p. 3; ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 9 March 1883, p. 3.

[18] ‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 8 May 1883, p. 3.

[19] ‘Managers’ reports’, Mercury, 30 June 1883, p. 2.

[20] ‘Our Special Reporter’ (Theophilus Jones), ‘The west coast tin mines’, Mercury, 31 May 1883, p. 3.

[21] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 1 August 1883, p. 3.

[22] According to Con Curtain and LJ Smith, companies which installed batteries included the Carn Brae (JT Rabling; 10 heads, from .H Knight’s Phoenix Foundry, Launceston), Orient (John Williams; Thomas S Williams; 10, Salisbury Foundry, Launceston), Cliff (John Hancock; William Williams; W Thomas; PT Young; Edward Perrow, 5), the West Cumberland (George Lightly; 5), the Wakefield (5), Cumberland (AB Gallacher; 10), the Montagu (Alex Ingleton; 15), the Victorian-registered Cornwall Tin Mining Co (Mark Gardiner; 10, WH Knight), and Peripatetic (Con Curtain; 10). Companies which did not install machinery included the Montagu Extended (Robert Hope Carlisle), Prince George (John Addis), St Clair (James Henry Nance), Champion (WG Hensley), Mount Heemskirk and Agnew (John Greenwood), Heemskirk River (Edwin Tremethick) and the St Dizier (Nicholas St Dizier). The Empress Victoria (Thomas Fowler) had a steam hoisting plant but no treatment plant. See Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’, Examiner, 27 February 1928, p. 5; and LJ Smith, ‘South Heemskirk tin mine’, Advocate, 11 August 1928, p. 14. Curtain claimed there were 75 heads of stampers on the field, but Smith’s list of batteries added up to 80 heads.

[23] Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old Times: Heemskirk Mines and Mining’. There is a five-head battery at the Carn Brea mine today.

[24] ‘Heemskirk’, Mercury, 23 October 1883, p. 3.

[25] Editorial review of 1883, Launceston Examiner, 1 January 1884, p. 2.

[26] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 3 April 1884, p. 3.

[27] Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’.

[28] AH Blissett, Geological survey explanatory report, One Mile Geological Map Series, Zeehan, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1962, p. 112.