DYI dentistry would make for intriguing reality TV (Channel Seven’s new blockbuster The chair anyone?) but in the nineteenth-century Tasmanian backwoods it was an everyday reality. Many people were far removed from medical services, and if you owned forceps you were licensed to operate. Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis (c1828–1912) was a model of self-sufficiency—hunter, stock rider, tanner, bootmaker, rug maker, leather worker, blacksmith, tool maker and dentist. Whether he aspired to more advanced surgery is unknown, but his prowess with the pincers must have made for some tense moments around the family dinner table.

Given that 40,000 years of Aboriginal custodianship are unrepresented on official charts of the area, it shouldn’t be surprising that Francis’s comparatively miniscule 40-year familiarity with this former Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) highland run is not recorded on its landmarks. Unlike his notable successor, Dave Courtney (recalled by Courtney Hill), the short, stocky Francis cut no memorable figure. He had no moustaches he could tie behind his back or thick beard to hide his face. Nor was he a ‘man of mystery’, as much as some might have preferred him to be. Francis’s convictism was unpalatable in some quarters even after his death. One newspaper editor omitted the words ‘though a prisoner for some trifling offence’ from his obituary.[1] Highland journalist Dan Griffin was less mealy-mouthed but confused Jack Francis the stockman with Jack Francis the builder and failed assassin.[2] Both men were transported from England to Van Diemen’s Land, the latter for taking pot shots at Queen Victoria, but Jack Francis the stockman was the most benign and pathetic of transportees, being a boy convicted of stealing a barometer.[3] These beginnings make his nickname ‘Jack the Shepherd’, recalling the notorious Irish outlaw, even more ironic.[4]

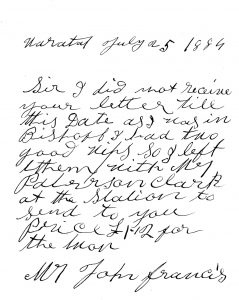

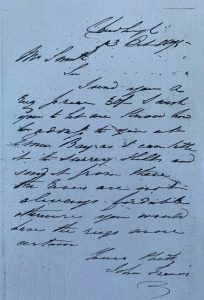

A native of County Armagh, Northern Ireland, Francis was apparently apprenticed as a ‘rough shoemaker’ when he faced court in Lancaster, Lancashire, England.[5] He probably had no idea how those skills would serve him in future years. Measuring all of 167 cm, he must have had a basic education. He could write, but with apparent difficulty, clearly preferring to dictate letters rather than write them himself.[6] Transported for seven years on the Egyptian in 1838, the boy convict served Launceston bootmaker Amos Langmaid before being assigned to rural masters James Grant at Tullochgorum near Fingal and Theodore Bartley at Kerry Lodge near Breadalbane.[7]

By now Francis was getting his leather in the field as well as at the end of an awl. After securing a certificate of freedom in 1845, he was a shepherd at Bentley near Chudleigh before securing his first posting to the highlands.[8] If childhood transportation to the antipodes hadn’t shaken his being to the core, his life now got a mite more adventurous. Because of Legislative Council parsimony, there were few public road bridges in northern Tasmania before 1865, but the VDL Co Track by which the highlands grazing runs were accessed from Chudleigh had dangerous fords much later than that. Negotiating the track for the first time, Francis and his two companions found the Mersey River almost impassable. Jim Garrett took the other two men’s clothes across on horseback, but with such difficulty that he could not return for the men, who of course had no chance of wading the torrent. They therefore had to spend the night without warm clothes or bedding, and were without food until late the next day when crossing became possible.[9]

This was probably in 1851 when grazier William Kimberley became the first victim of a beautiful mirage called the Vale of Belvoir. In that year Kimberley leased 1000 acres of this snowy glacial valley as a summer sheep run, posting Francis as their protector.[10] Barometer boy apparently had more of an issue with ‘wolves’ than with the highland weather. Thylacines—but more likely wild dogs—were said to have decimated Kimberley’s flock, although the survivors thrived, some being too fat to travel.[11]

Perhaps tubby sheep were Francis’s passport to the overseer’s position at Fields’ Middlesex Plains Station. This was a lonely, isolated job, with only the annual muster party and the occasional prospector like James ‘Philosopher’ Smith or surveyor like Charles Gould to interrupt proceedings. However, a routine of maintaining fences, preventing liver fluke in sheep, rescuing stock from bogs and patch-burning the runs left plenty of time for the hunter-stockman’s real occupation, snaring and hunting—primarily for the fur industry, secondarily for meat.

The stock-in-trade of the highland stockman was the brush-possum-skin rug. The cold highland climate necessitated thick furs, and Francis, with his expertise in leatherworking, was well placed to take advantage of the demand for this specifically Tasmanian product.[12] Possum-skin carriage rugs and stock-whips he sold to VDL Co agent James Norton Smith fetched £2 and 16 shillings each respectively.[13] This was useful money, given that a stockman or shepherd’s annual wage was in the range of only £20–£30, supplemented by rations (flour, sugar, tea, tobacco, perhaps potatoes and some meat) delivered to a depot on Ration Tree Creek at the foot of Gads Hill, the milk he could wring from a cow, a few skilling sheep and an abundance of wallaby and wombat meat. He would have grown a few hardy vegetables, guarding them against frost and snow.

From VDL22/1/9 and VDL22/1/12 (TAHO) respectively.

Not every woman would have fancied the lifestyle, but plenty of Jack’s contemporaries were accustomed to hardship. Jack Francis married 29-year-old house maid and factory worker Maria Bagwell (c1830–83) at Deloraine in 1860, subordinating his Roman Catholicism to her Protestantism.[14] She had been transported for seven years for stealing barley meal in Somerset in 1849. Perhaps she needed the nourishment, measuring only 166 cm as a nineteen-year-old. Her prison record is littered with the phrase ‘existing sentence of hard labour extended’. In 1852 she had been ‘delivered of’—deprived of?—an ‘illegitimate child’ at the Female House of Correction.[15] What happened to this unnamed girl from an unnamed father? Just as elusive is George Francis (?–1924), the child apparently born to Jack and Maria Francis during their time at Middlesex.[16]

The house maid seems to have taken to station life. In 1865 Maria Francis escorted surveyors James Calder and James Dooley from Middlesex Station to Chudleigh. To their ‘amazement’, their guide sat astride her horse like a man

‘and thus rode the whole way … with an amount of unconcern that surprised us not a little; and as if determined that we should not lose sight of this extraordinary feat of horsewomanship, she rode in front of us almost the whole distance, smoking a dirty little black pipe from one end of the journey to the other’.[17]

The couple’s son George Francis had arrived by 1871, when a child was mentioned by a visitor to Middlesex. Now Jack Francis revealed himself to be not just a skilled shoemaker and possum-skin rug maker but an expert tanner, clothing himself and his family in leather. They lived

‘in a clean and comfortable hut. A very few minutes sufficed for Mrs Francis to give us a cup of good tea, with abundance of milk, toast, and bread and butter, and when bedtime came she provided us with flealess bed-clothes, an unusual luxury in the bush….’

Jack Francis was ‘a very handy fellow … adept at shoeing a horse or drawing a tooth, having himself made a first-rate pair of forceps with which to perform this last-named operation …’ [18]

Today not even a headstone in the Old Chudleigh Cemetery records this go-getter’s existence. Around Middlesex Station the ‘old’ European names are forgotten: Misery (now Courtney Hill), the Sirdar (after Horatio Herbert Kitchener of the South African War), Pilot, Sutelmans Park, Vinegar Hill, Twin Creeks. Who named them all and why? No journalist interviewed the old station hands. Yet while the Francises left their mark only in written history, digitisation of archival records is enriching our knowledge of displaced people like them, who lived remarkable lives in remote places.

[1] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[2] ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

[3] See conduct record for John Francis, transported on the Egyptian for seven years in 1839, CON31/1/12, image 175 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-12$init=CON31-1-12p175, accessed 16 February 2020.

[4] For the nickname see, for example, ‘River Don’, Weekly Examiner, 4 October 1873, p.11; ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[5] Francis’s obituarist in, for example, ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4, claimed that he was born at Woodburn, Buckinghamshire, 5 February 1828. Francis’s convict records make him a native of County Armagh.

[6] Indent for John Francis, CON14/1/48, images 25 and 26 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/tas/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fARCHIVES_DIGITISED$002f0$002fARCHIVES_DIG_DIX:CON14-1-48/one, accessed 16 February 2020. Compare, for example, his letter to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO), written by his wife Maria Francis, with his letter to James Norton Smith, 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO), written in his own hand after Maria’s death.

[7] Conduct record, as above.

[8] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[9] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[10] ‘Crown lands’, Courier, 5 February 1851, p.2; ‘Surveyor-General’s Office’, Courier, 3 December 1851, p.2; ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[11] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[12] HW Wheelright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[13] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 10 October 1873, NS22/1/4; and 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO).

[14] Married 24 December 1860, marriage record no.657/1860, at St Mark’s (Anglican) Church, Deloraine, RGD37/1/19 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages&qf=NI_NAME_FACET%09Name%09Francis%2C+John%09Francis%2C+John, accessed 15 February 2020. On his marriage certificate, Jack underestimated his age as 28 years.

[15] See conduct record for Maria Bagwell, transported on the St Vincent, CON41/1/25, image 16 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON41-1-25$init=CON41-1-25p16, accessed 15 February 2020. See also birth record for Maria Bagwell’s unnamed illegitimate female child, born 7 September 1852, birth record no.1780/1852, registered at Hobart, RGD33/1/4 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=NI_NAME%3D%22Bagwell,%20Maria%22#, accessed 15 February 2020.

[16] George Francis died 12 January 1924, will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages+%7C%7C+Deaths%09Deaths+%7C%7C+Wills%09Wills&qf=PUBDATE%09Year%091906-1976%091906-1976, accessed 16 February 2020.

[17] James Erskine Calder, ‘Notes of a journey’, Tasmanian Times, 18 May 1867, p.4.

[18] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.