In 1889 Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) local agent James Norton Smith advertised for ‘a trustworthy man to snare tigers [thylacines or Tasmanian tigers], kangaroo, wallaby and other vermin at Woolnorth’, the company’s large grazing property at Cape Grim. The annual wage was £30 plus rations and a £1 bounty for each thylacine killed.[1] Applications came from Tasmanian centres as far afield as Branxholm in the north-east and New Norfolk in the south. One, written on behalf of her husband, came from Rachel Nichols of Campbell Town. She was the mother of then eleven-year-old Ethelbert (Bert) Nichols, the future hunter, Overland Track cutter, highland guide and Lake St Clair Reserve ranger.[2]

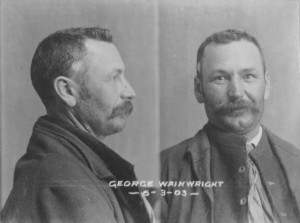

However, none of these applicants got the job. The man chosen as ‘tigerman’, as the position was known within the VDL Co, was George Wainwright senior, who arrived ‘under a cloud’ as George Wilson and departed in 1903 when convicted of receiving stolen skins.[3] Was he a relation of Woolnorth overseer James Wilson, or how was he selected for the job?[4] And what was a tigerman anyway?

George Wainwright was born in Launceston in 1864, and seems to have a not untypical upbringing for the poorly educated child of an ex-convict father, featuring family breakdown, petty crime, shiftlessness and suggestions of poverty.[5] As a young adult he measured only 162 cm (5 foot 3 inches), with a dark complexion and dark curly hair. The scar under his chin may have the result of rough times on the streets of Launceston.[6] Food may have been scarce. At thirteen he faced court with another boy on a charge of stealing apples (the case was dismissed for lack of evidence).[7] In 1883, his employer, Launceston butcher Richard Powell, had the nineteen-year-old arrested on warrant (that is, in absentia) on a charge of breaching the Master and Servant Act.[8] He had run off to Sydney, describing himself as a cook.[9]

George had returned to Launceston by October of that year, when his mother, now known as ‘Mrs T Barrett’ (née Caroline Hinds or Haynes or Hyams), ran a public notice instructing clergymen not to marry her son to anyone, he being under age.[10] Presumably George had Matilda Maria Carey (1863–1941)—or her pregnancy—in mind, because the couple were soon united, and soon separated.[11] In 1885 Matilda prosecuted George for deserting her and George junior, having not sent her any money for six months. It was revealed in court in Melbourne that George had recently been a grocer’s assistant, but now was working in a Brunswick (Melbourne) brick yard. Matilda Wainwright was then living with her father-in-law William Wainwright in Launceston. She claimed he showed her little sympathy, having sold all her furniture and told her to seek a living for herself. George Wainwright was freed on agreeing to pay her 10 shillings per week.[12]

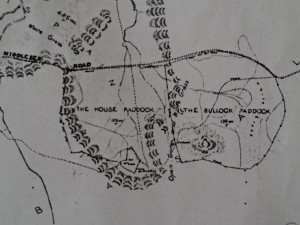

Interestingly, in Victoria he was known to police as George Brown, ‘alias Wainwright’.[13] Presumably he returned to Launceston sometime between 1885 and 1889—and changed his name to George Wilson! He may have been the George Wilson who was in Beaconsfield in 1886 and 1887.[14] Perhaps he became a protégé of James Wilson, the Woolnorth overseer, and perhaps that man’s intervention secured Wainwright/Brown/Wilson the tigerman job at Woolnorth. James Wilson had coined the term ‘tigerman’ to describe the Mount Cameron West shepherds in the period 1871–1905. Convinced that thylacines were killing their sheep, the VDL Co gave the Mount Cameron West man the additional job of maintaining a line of snares across a narrow neck of land at Green Point, which was believed to be the predator’s principal access point to Woolnorth. Otherwise, the tigermen were actually standard stockmen-hunters, charged with guarding sheep and destroying competitors for the grass.

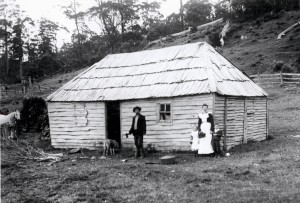

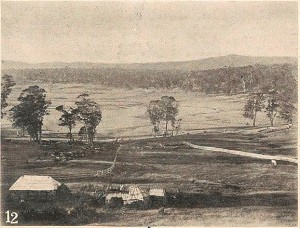

George Wilson and his family originally occupied a one-room hut at Mount Cameron West. In 1893 George Wainwright, as he was now known again, apparently told a visitor that he received £2-10 for each thylacine killed—£1 from the VDL Co, £1 from the government and 10 shillings for the skin. In the years 1888–1909 the Tasmanian government paid a bounty on every thylacine carcass submitted to police. However, nobody by the name of Wainwright ever collected a government bounty: in fact only two VDL Co tigermen, Arthur Nicholls and Ernest Warde, personally collected government bounties while working for the company.[15] The thylacine carcasses appear to have been sold through intermediaries, chiefly Stanley merchants Charles Tasman (CT) Ford (1891–99) and (after Ford’s death) William B (WB) Collins (1900–06). Ford, who also drove cattle down the West Coast to Zeehan and bought VDL Co stock, was a regular visitor to Woolnorth.[16]

In 1893 Wainwright had about 60 springer snares set for wallaby, pademelon and brush possum.[17] Ringtails were the dubious beneficiary of technological change, as the commercial manufacture of acetylene or carbide during the 1890s revolutionised ‘spotlighting’. Using an acetylene lamp to spotlight nocturnal animals was a vast improvement on the traditional method of shooting by moonlight, since some animals, especially the ringtail possum and ‘native cat’, were ‘hypnotised’ by the lamp, remaining rooted to the spot. It was not the ideal hunting technique for a grazing run, however, let alone for a solitary shepherd. Usually, two men worked together, one ‘spotting’ the animals with the acetylene lamp, the other shooting them. The lamps which shooters used frightened stock, and sometimes shooters’ dogs ran amok with grazing sheep. More significantly for the hunter, shooting the animal in any other part but the head damaged its pelt. Acetylene fumes were also unpleasant for the hunter, and the battery sometimes gave him an unexpected ‘charge’.

More money was available for a living tiger than a dead one. By Wainwright’s time, thylacines were in demand from zoos. In 1892 James Denny caught one alive at the Surrey Hills and sent it to the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne.[18] In 1896 CT Ford was asked to procure live tigers for a circus. Wainwright obliged by capturing a thylacine alive and sending it into Stanley, where there was ‘a little excitement … to see “the tiger”’ before it was shipped to Sydney.[19] This thylacine capture does not appear in the extant Woolnorth farm journal record (the journal for 1896 is missing) or in any other surviving official records for Woolnorth. Since the animal was not killed, Wainwright received no VDL Co or government reward for it.

In 1897–98 a new hut was built for George and Matilda at Mount Cameron. They would need it. Six children—George, Alf, Dick, May, Harry, Gertrude and Robert—gave them plenty to worry about in such an isolated place. If that was not enough, Matilda was reportedly ‘very ill’ in July 1893 and ‘badly hurt’ in January 1894, while in May 1900 Woolnorth overseer W Pinkard had to fetch medicine for her from Stanley.[20]

By 1900 George and Dick were already showing their prowess as tiger snarers, and one of the Wainwright boys was digging potatoes.[21] With their father sometimes helping out elsewhere on the property, fetching cattle from Ridgley or a stockman from Trefoil Island, the children quickly developed a range of skills which ensured that they could work on the land independently.[22]

Wainwright’s imprisonment in 1903 gave them that opportunity. The story of his crime of receiving 298 wallaby, 298 pademelon, 17 tiger cat, 2 domestic cat and 10 brush possum skins stolen from William Charles Wells contains insight into hunting at Mount Cameron West and on Woolnorth generally. Wells was caretaker (hunter-stockman) for a farm at Green Point south of Woolnorth, near where the VDL Co arranged its snares. The owner of the property, Thomas John King, had stayed with Wainwright in the Mount Cameron Hut in July 1902 after fetching the skins from the farm. The skins disappeared overnight after being left outside the hut in a cart. Suspicion fell on Wainwright not only because his was the only hut in the area but because he had previously tried to buy the skins at a price which was refused. Police alleged that in September Matilda Wainwright drove a buggy containing the skins to the port at Montagu to be loaded on the ketch Ariel.[23] It was now close season, so Wainwright wrote telling Stanley storekeeper WB Collins that he was sending down some out-of-season skins and suggesting that he ask the police to let them pass. Wells claimed to have identified 23 of his stolen skins in Collins’ store.[24] Proof that Wainwright was guilty centred on Wells’ identification of an unusually light skin among those Wainwright had sent to market. A search conducted among the skins of three Launceston skin merchants, Lees, Sidebottom and Gardner, revealed only three or four skins matching the one identified by Wells, confirming the distinctiveness of the skin and strengthening the case against Wainwright.[25]

Launceston merchant Robert Gardner testified that he had known Wainwright for 25 years, having employed him when he (Wainwright) was a boy, and that he had done business with him for several years, finding him straightforward and honest. He had bought wallaby skins from Wainwright regularly.[26] Despite this testimonial, Wainwright was given a twelve-month sentence for receiving stolen property. Thirty-nine years old, he died in the Hobart Gaol of heart failure prompted by acute pneumonia only four months into that sentence.[27]

Today a relatively young man’s death in custody would provoke an inquest. However, the harshness of Wainwright’s demise seems in keeping with the harshness of his sentence and the general torpor of working people’s lives more than a century ago. George must have done something right as a hunter and provider, because he left wife Matilda £305—more than ten times his annual stockman’s wage.[28]

Charged with nothing, Matilda Wainwright stayed on as cook at Woolnorth, although only because no one else could be found for the job. ‘I would have preferred anyone else rather than Mrs Wainwright’, new VDL Co agent AK McGaw lamented, ‘and now that she is there I am not altogether satisfied that her influence is for the best. Of course I find her appointment does not answer I will have no hesitation in terminating it’.[29] McGaw had advertised for a married couple to replace the Wainwrights.[30] He effectively got one when the widowed Matilda married the new overseer, Thomas Lovell, while her sons, good workmen, also had a future at Woolnorth. As a woman and mother, remarriage was her only option anyway. George Wainwright junior would carve out his own long career as a VDL Co stockman.

[1] ‘Wanted, at Woolnorth’, Daily Telegraph, 9 August 1889, p.1.

[2] Rachel Nichols to James Norton Smith, 8 August 1889, VDL22/1/19 (Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office [afterwards TAHO]).

[3] AW McGaw, Outward Despatch no.16, 1 June 1903, p.151, VDL7/1/13 (TAHO); ‘Death of a prisoner’, Mercury, 15 July 1903, supplement p.6.

[4] On the bottom of J Lowe’s application for the job is written in pencil ‘Geo Wilson also’. Everett was the reserve choice: on the back of his application is written ‘If man, at present engaged—not successful will write JL again’. See J Lowe application 9 August 1889 and J Everett application, 19 August 1889, VDL22/1/19 (TAHO).

[5] For William Wainwright (1810–87), see conduct record, CON33-1-90, TAHO website, http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-90,207,205,F,60, accessed 17 December 2016.

[6] ‘Miscellaneous information’, Victoria Police Gazette, 19 August 1885, p.232.

[7] Birth registration 60/1864, Launceston; ‘Police Court’, Cornwall Chronicle, 7 February 1877, p.3.

[8] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Tasmanian, 22 April 1882, p.432; ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 7 February 1883, p.3.

[9] He arrived in Sydney from Launceston on the Esk, 9 February 1883, New South Wales, Australia, Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1826–1922.

[10] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 31 October 1883, p.1.

[11] Marriage registration 677/1883, Launceston. They married 7 November 1883, George William Wainwright was born seven months later, on 12 June 1884, birth registration 371/1884, Launceston. Matilda Maria Carey was born in Launceston, 22 December 1863, registration 23/1864, Launceston.

[12] ‘Wife desertion’, Launceston Examiner, 29 August 1885, p.2.

[13] ‘Miscellaneous information’, Victoria Police Gazette, 19 August 1885, p.232.

[14] ‘Beaconsfield’, Daily Telegraph, 29 May 1886, p.3; ‘Beaconsfield’, Launceston Examiner, 15 January 1887, p.12.

[15] Nicholls: bounties no.289, 14 January 1889, p.127; and no.126, 29 April 1889, p.133, LSD247/1/1. Warde: bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, p.325, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] James Wilson to JW Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[17] Austin Allom, ‘A trip to the west coast’, Daily Telegraph, 19 August 1893, p.7.

[18] ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 17 September 1892, p.2.

[19] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[20] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 10 July 1893, VDL277/1/20; 22 January 1894, VDL277/1/21; and 7 May 1900, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[21] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 13 and 14 June, 7 May 1900, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[22] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 22 September 1898, VDL277/1/24; 16 January and 5 March 1899, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[23] ‘Supreme Court’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 14 November 1902, p.2.

[24] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 15 November 1902, p.3.

[25] ‘The Wainwright case’, Examiner, 28 February 1903, p.6.

[26] ‘The Wainwright case’, Examiner, 27 February 1903, p.6.

[27] ‘Death of a prisoner’, Examiner, 15 July 1903, p.6.

[28] ‘Testamentary’, Mercury, 20 October 1903, p.4.

[29] AK McGaw to VDL Co Board of Directors, no.38, 2 November 1903, p.313, VDL7/1/13 (TAHO).

[30] Advert, Examiner 20 May 1903, supplement p.8.