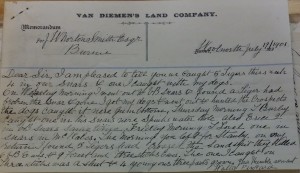

How do you stigmatise an animal? Try branding. The change from ‘hyena’ to ‘tiger’, as the common descriptor for the thylacine, was a major step in its reinvention as a sheep killer. Both ‘tiger’ and ‘hyena’ were used commonly to describe the thylacine during much of the nineteenth century, with ‘tiger’ only becoming the dominant term late in that century and into the twentieth century. For example, the records of the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) show that the company’s local officers used ‘hyena’ almost universally to describe the thylacine during the company’s first period of farming its Woolnorth property, in the years 1827–51—whereas later they went exclusively with ‘tiger’.

The stripes on the thylacine’s back presumably prompted the original attributions of the names ‘tiger’ and ‘hyena’, by Robert Knopwood and CH Jeffreys respectively.[1] The Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) and the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) were mentioned regularly in nineteenth-century newspaper items about life in the British Raj, which some foreign-born Tasmanians had also visited. Tigers, leopards, cheetahs, wolves and, less often, hyenas, preyed on stock and sometimes people in India. Government rewards were offered there for killing tigers. While the fearsome tiger was the favourite ‘sport’ of Indian big game hunters, the hyena, unlike its some-time Tasmanian namesake, was not the primary carnivore in the Bengali ecology. It was sometimes reported to be ‘cowardly’, ‘skulking’ and lacking in the fight desired by the game hunter.[2]

Likewise, the thylacine was also often described as ‘cowardly’ in its alleged sheep predations.[3] By the 1870s and 1880s, however, when the profitability of the wool industry was declining, those employed in the industry seem to have used the term ‘tiger’ almost universally to describe the thylacine. Perhaps shepherds preferred ‘tiger’ because it glamorised their profession, introducing an element of danger and likening them to the big game hunters of India. The way in which some thylacine killers made trophies of their kills and were photographed with these suggests identification with big game hunting.[4] By the same token, dubbing the thylacine a ‘tiger’ provided a potential scapegoat for sheep losses, enabling the shepherd to shift the blame for his own poor performance on to what may henceforth be perceived as a dangerous predator. Wool-growers wanting to eliminate the thylacine would also be keen to cast it as a dangerous predator. John Lyne, the east coast wool-grower who led the campaign for a government thylacine bounty, referred to the animal as a ‘tiger’ but also as a ‘dingo’, thereby equating the thylacine with the well-known mainland Australian sheep predator.[5] In 1887 ‘Tiger Lyne’s campaign was mocked to the effect that

‘the jungles of India do not furnish anything like the terrors that our own east coast does in the matter of wild beasts of the most ferocious kind. According to ‘Tiger Lyne’, these dreadful animals [thylacines] may be seen in their hundreds stealthily sneaking along, seeking whom they may devour …’[6]

The VDL Co correspondence records show that the company’s local agent James Norton Smith also originally described the thylacine as a ‘hyena’. He appears to have adopted ‘tiger’ as a descriptor in 1872 after his Woolnorth overseer, Cole, used the term in a letter to him. James Wilson, Woolnorth overseer 1874–98, also used the term ‘tiger’ exclusively, and after 1876 Norton Smith followed suit. The term ‘hyena’ was not used in any correspondence written or compiled by VDL Co staff, in Woolnorth farm journal records or Woolnorth accounting records in the years 1877–99. While Norton Smith occasionally used the term ‘hyena’ in the years following Wilson’s retirement from Woolnorth, ‘tiger’ remained his preferred term and this continued to be used exclusively at Woolnorth.

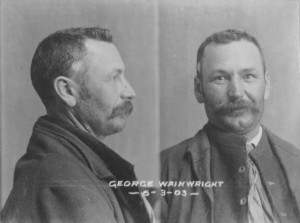

Theophilus Jones: thylacine prosecutor

As Robert Paddle and others have suggested, pastoralists generally blamed the thylacine as well as the rabbit for their declining political power and wealth.[7] One of the greatest prosecutors of the thylacine at this time was Theophilus Jones. In 1877–78 and 1883–85 two young British journalists toured Tasmania writing serialised newspaper accounts of its districts. Since both were newcomers, with limited knowledge of the colony, they could be expected to repeat unquestioningly much of what they were told. The first of these writers, E Richall Richardson, travelled all the populated regions of Tasmania except the far north-west and Woolnorth. On the east coast, Richardson interviewed woolgrowers, including John Lyne, the MHA for Glamorgan who a decade later would petition to establish the thylacine bounty. Richardson’s only comment upon the thylacine as a sheep killer or any kind of nuisance in his 92-part series was not on the east coast or in the Midlands, but in reference to the twice-yearly visits of graziers to their Central Plateau stock runs:

‘If when the master comes up, and there is a deficit in the flock, the rule is ‘blame the tiger’. The native tiger is a kind of scape-goat amongst shepherds in Tasmania, as the dingo is with shepherds in Queensland; or as ‘the cat’ is with housemaids and careless servants all over the world. ‘It was the cat, ma’am, as broke the sugar-basin’; and ‘It was the tigers, sir, who ate the sheep’.[8]

Theophilus Jones, in his 99-part series written in the years 1883–85, told a different tale. By this time, only half a decade since Richardson wrote, the wool industry had declined markedly. The first ‘stock protection’ association, that is, a locally subscribed thylacine bounty scheme, was formed at Buckland on the east coast in August 1884 while Jones was touring the area.[9]

Jones’ circumstances were different to the earlier writer’s. Although travelling in poverty, Richardson was a single man with no commitments. Jones, on the other hand, was trying desperately to support a wife and large family. While travelling Tasmania as a newspaper correspondent, he doubled as an Australian Mutual Provident (AMP) assurance salesman. Much more than Richardson, Jones concentrated on populated areas where he might sell assurance and find well-to-do patrons. He not only visited Woolnorth but practically every large grazier in the colony, and he flattered men who were in a position to financially benefit him. Whether currying favour or being merely ignorant of the truth, it is not then surprising to find Jones spouting woolgrowers’ vituperative against the thylacine. Henry, John and William Lyne appear to have fed Jones a litany of almost six decades of warfare with Aborigines and the wildlife, as if these were age-old predators: ‘Blacks and tigers made the life of a young shepherd one of continued mental strain’.[10] For Jones the tiger was generally the biggest killer of sheep, followed by the devil and the ‘eaglehawk’. The thylacine had ‘massive’ jaws, ‘serrated’ teeth and a powerful body like that of a kangaroo dog.[11] It was ‘a great coward’, savaging lambs but refusing battle with man or dog.[12] Jones applauded the stock protection association, hoping that it would reduce eagles and tigers ‘to the last specimen’.[13] That is, drive them to extinction.

Jones had already visited Woolnorth. He found that, like his predecessors, tigerman Charlie Williams kept ‘trophies’ at Mount Cameron, his prize being a thylacine skin 2.3 metres long.[14]

Like Williams, the government was actually more interested in possums. It had cited increased hunting, in response to high skin prices, as a reason to introduce the Game Protection Amendment Act (1884), which protected all kinds of possum during the summer, allowing open season from April to July inclusive. During debate about the bill in the House of Assembly, James Dooley ‘likened the sympathy for the native animals to that which was excited in favour of the native race’, to which MHA for Sorell, James Gray, responded that ‘the only resemblance between the natives and the opossums were that they were both black. (Laughter.)’[15]

It was also Gray who in 1885 asserted the ‘necessity of something being done to stop the ravages of the native tiger in the pastoral districts of the colony …’.[16] John Lyne took up this stock protection measure: a £1 per head thylacine bounty operated from 1888 to 1909. About 2200 bounties were paid across Tasmania, helping to drive the animal towards extinction. Bounties were paid by the Colonial Treasurer upon thylacine carcasses being presented to local police magistrates or wardens.

Woolnorth was a remote settlement with challenges faced by few wool-growing properties. Distance from towns, doctors and schools was probably one reason that it was so difficult to find and keep a reliable man to work at Mount Cameron West in particular. Time and time again James Wilson’s farm journals record the Mount Cameron West shepherd’s monthly visits to the main farm at Woolnorth to get supplies and return with them to his own hut: ‘Tigerman came down’ and ‘Tiger went home’. ‘Tigerman’, which carries the implication of being a dedicated thylacine killer, may have been coined to glamorise the position in order to attract staff. It and the general use of the term ‘tiger’ at Woolnorth may also indicate that the overseer, his stockman and farm hands wanted to shift the blame for sheep losses on the property.

Table 3: Occurrences of various names for the thylacine in Tasmanian newspapers for the years 1816–1954 (in both text and advertising), taken from the Trove digital newspaper database 22 December 2016

| NAME | 1816–87 | 1888–1909 | 1910–54 | TOTAL |

| Tasmanian tiger | 141 (84–57) | 96 (64–32) | 434 (420–14) | 671 (568–103) |

| Native tiger | 326 (199–127) | 197 (186–11) | 88 (88–0) | 611 (473–138) |

| Tasmanian native tiger | 5 (5–0) | 0 (0–0) | 7 (7–0) | 12 (12–0) |

| Thylacine/thylacinus | 43 (43–0) | 20 (20–0) | 93 (91–2) | 156 (154–2) |

| Hyena/native hyena/opossum hyena | 165 (107–58) | 46 (39–7) | 84 (77–7) | 295 (223–72) |

| Dog-faced opossum | 1 (1–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (1–0) |

| Tasmanian wolf | 9 (3–6) | 11 (11–0) | 97 (97–0) | 117 (111–6) |

| Marsupial wolf | 4 (4–0) | 6 (6–0) | 74 (74–0) | 84 (84–0) |

| Tiger wolf | 7 (7–0) | 3 (3–0) | 3 (3–0) | 13 (13–0) |

| Native wolf/native wolf-dog | 5 (5–0) | 0 (0–0) | 5 (5–0) | 10 (10–0) |

| Zebra wolf | 5 (5–0) | 6 (6–0) | 2 (2–0) | 13 (13–0) |

| Tasmanian tiger wolf | 1 (1–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (1–0)[17] |

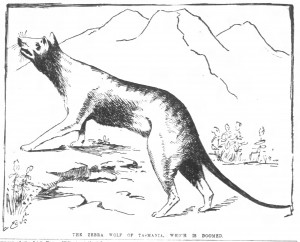

In her book Paper tiger: how pictures shaped the thylacine, Carol Freeman stated that ‘Tasmanian wolf’ and ‘marsupial wolf’ were the principal names given to the thylacine in the zoological world until well into the twentieth century, described how in the period from the 1870s to the 1890s ‘wolf-like’ visual images of the species predominated in natural history literature, and speculated that illustrations of this kind, repeated in mass-produced Australian newspapers in 1884, 1885 and 1899, ‘influenced perceptions close to the habitat of the thylacine and encouraged government extermination policies’.[18]

The National Library of Australia’s Trove digital newspaper database allows us to test the idea that the depiction of the thylacine as a ‘wolf’ or as ‘wolf-like’ had any traction in Tasmania. Unlike the inter-colonial illustrated newspapers to which Freeman referred—Australian Graphic (1884), Illustrated Australian News (1885) and Town and Country Journal (1899)—the Trove search represented by Table 3 is restricted to 88 Tasmanian newspaper titles, 23 of which published during at least part of the period of the Tasmanian government thylacine bounty 1888–1909. More than any other type of publication, the Tasmanian newspapers are likely to contain the language of ordinary Tasmanians, expressed either by journalists, newspaper correspondents or by themselves in letters to the editor—and they were more likely than any other form of publication to be read by and contributed to by graziers, legislators and hunter-stockmen involved in killing thylacines. Some of these newspapers carried occasional lithographed or engraved images, but the search does not include the two best-known Tasmanian illustrated newspapers, the Weekly Courier (1901–35) and the Tasmanian Mail/Illustrated Tasmanian Mail (1877–1935), which (in December 2016) were yet to be digitised for the Trove database. Trove coverage of Tasmanian newspapers begins with the Hobart Town Gazette and Southern Reporter in 1816 and goes no later than 1954 except in a few cases.

The Trove search suggests that in the period 1888–1909 the terms ‘native tiger’ (197 hits) and ‘Tasmanian tiger’ (96 hits) were much more widely used by the general public in Tasmania that any permutation of ‘wolf’ (26 hits altogether), and that ‘hyena’ (46 hits) was also more popular than ‘wolf’. While the 1884 issue of Australian Graphic which contained the illustration of the ‘Tasmanian zebra wolf’ is not included in the Trove search, it did pick up a description of that issue of the newspaper by the editor of the Mercury. Clearly he was not profoundly influenced by the engraving of the thylacine:

‘The illustrations are fairly good, excepting those which are apparently intended to be amusing; these amuse only by their extreme absurdity. There is a cut representing, what is termed, a Tasmanian zebra wolf. It is about as true to nature as the pictures exhibited outside a travelling menagerie’.[19]

The names ‘Tasmanian wolf’ (97 hits) and ‘marsupial wolf’ (74 hits) only gained traction in Tasmanian newspapers in the period (1910–54) when the thylacine was clearly disappearing or virtually extinct, that is, when the scientific and zoological community entered the popular press in its desperate search for a remnant thylacine population. This is also the period in which the Latin scientific name for the animal, thylacine, thylacinus (93 hits) occurred much more frequently in the Tasmanian press. However, even in this period, ‘tiger’ (529 hits) remained easily the predominant descriptor for the thylacine. The fact that the thylacine received more attention in the press during the years when it could not be found than when it could speaks for itself, although of course many more newspapers were published in the first half of the twentieth century than in the nineteenth.

[1] Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian tiger: a lesson to be learnt, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, 1998, p.15.

[2] ‘Pigsticking in India’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1897, p.3; ‘Shikalee’, ‘Wild sport in India’, Launceston Examiner, 24 July 1897, p.2.

[3] See, for example’, ‘Royal Society of Tasmania’, Courier, 16 June 1858, p.2; or ‘Town talk and table chat’, Cornwall Chronicle, 27 March 1867, p.4.

[4] See, for example, [Theophilus Jones], ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[5] See, for example, ‘Parliament’, Launceston Examiner, 1 October 1886, p.3.

[6] Tasmanian Mail, 3 September 1887; cited by Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000, p.161.

[7] See Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger.

[8] E Richall Richardson, ‘Tour through Tasmania: no.89: cattle branding’, Tasmanian Tribune, 14 March 1878, p.3.

[9] ‘Buckland’, Mercury, 15 August 1884, p.3.

[10] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.61’, Mercury, 8 November 1884, supplement, p.1.

[11] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.49’, Mercury, 26 July 1884, p.2.

[12] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[13] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.56’, Mercury, 20 September 1884, p.2.

[14] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[15] ‘House of Assembly’, Mercury, 24 October 1884, p.3.

[16] ‘Meeting at Buckland’, Mercury, 14 August 1884, p.2; ‘The native tiger’, Mercury, 25 September 1885, p.2.

[17] This list was compiled on 22 December 2016. The numbers in brackets indicate how many of the hits occurred in text and how many in advertising. While occurrences of a name in advertising are a relevant gauge of its public usage, it is recognised that numbers of hits are exaggerated by repeated publication of the same advertisement. Another issue noted in this search of Trove was the need to weed out references to ‘native and tiger cats’, which refer to the two species of quoll rather than to the thylacine. There are also cases of repetition in the sense that some textual references involve two or more names for the thylacine, such as ‘the Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf’. In such cases both names have been included in the table.

[18] Carol Freeman, Paper tiger: how pictures shaped the thylacine, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.117and 140.

[19] Editorial, Mercury, 28 March 1884, p.2.