by Nic Haygarth | 06/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

DYI dentistry would make for intriguing reality TV (Channel Seven’s new blockbuster The chair anyone?) but in the nineteenth-century Tasmanian backwoods it was an everyday reality. Many people were far removed from medical services, and if you owned forceps you were licensed to operate. Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis (c1828–1912) was a model of self-sufficiency—hunter, stock rider, tanner, bootmaker, rug maker, leather worker, blacksmith, tool maker and dentist. Whether he aspired to more advanced surgery is unknown, but his prowess with the pincers must have made for some tense moments around the family dinner table.

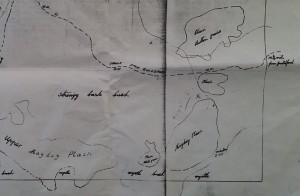

From Chudleigh to Waratah, including the Field brothers’ stations of Middlesex Plains and Gads Hill. Map courtesy of DPIPWE.

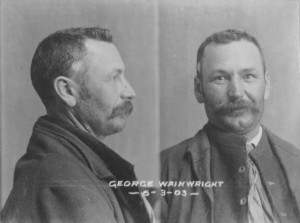

Given that 40,000 years of Aboriginal custodianship are unrepresented on official charts of the area, it shouldn’t be surprising that Francis’s comparatively miniscule 40-year familiarity with this former Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) highland run is not recorded on its landmarks. Unlike his notable successor, Dave Courtney (recalled by Courtney Hill), the short, stocky Francis cut no memorable figure. He had no moustaches he could tie behind his back or thick beard to hide his face. Nor was he a ‘man of mystery’, as much as some might have preferred him to be. Francis’s convictism was unpalatable in some quarters even after his death. One newspaper editor omitted the words ‘though a prisoner for some trifling offence’ from his obituary.[1] Highland journalist Dan Griffin was less mealy-mouthed but confused Jack Francis the stockman with Jack Francis the builder and failed assassin.[2] Both men were transported from England to Van Diemen’s Land, the latter for taking pot shots at Queen Victoria, but Jack Francis the stockman was the most benign and pathetic of transportees, being a boy convicted of stealing a barometer.[3] These beginnings make his nickname ‘Jack the Shepherd’, recalling the notorious Irish outlaw, even more ironic.[4]

Jack Francis and Dan Griffin at the Chudleigh Races, from the Weekly Courier, 23 January 1904, p.23.

A native of County Armagh, Northern Ireland, Francis was apparently apprenticed as a ‘rough shoemaker’ when he faced court in Lancaster, Lancashire, England.[5] He probably had no idea how those skills would serve him in future years. Measuring all of 167 cm, he must have had a basic education. He could write, but with apparent difficulty, clearly preferring to dictate letters rather than write them himself.[6] Transported for seven years on the Egyptian in 1838, the boy convict served Launceston bootmaker Amos Langmaid before being assigned to rural masters James Grant at Tullochgorum near Fingal and Theodore Bartley at Kerry Lodge near Breadalbane.[7]

By now Francis was getting his leather in the field as well as at the end of an awl. After securing a certificate of freedom in 1845, he was a shepherd at Bentley near Chudleigh before securing his first posting to the highlands.[8] If childhood transportation to the antipodes hadn’t shaken his being to the core, his life now got a mite more adventurous. Because of Legislative Council parsimony, there were few public road bridges in northern Tasmania before 1865, but the VDL Co Track by which the highlands grazing runs were accessed from Chudleigh had dangerous fords much later than that. Negotiating the track for the first time, Francis and his two companions found the Mersey River almost impassable. Jim Garrett took the other two men’s clothes across on horseback, but with such difficulty that he could not return for the men, who of course had no chance of wading the torrent. They therefore had to spend the night without warm clothes or bedding, and were without food until late the next day when crossing became possible.[9]

This was probably in 1851 when grazier William Kimberley became the first victim of a beautiful mirage called the Vale of Belvoir. In that year Kimberley leased 1000 acres of this snowy glacial valley as a summer sheep run, posting Francis as their protector.[10] Barometer boy apparently had more of an issue with ‘wolves’ than with the highland weather. Thylacines—but more likely wild dogs—were said to have decimated Kimberley’s flock, although the survivors thrived, some being too fat to travel.[11]

Perhaps tubby sheep were Francis’s passport to the overseer’s position at Fields’ Middlesex Plains Station. This was a lonely, isolated job, with only the annual muster party and the occasional prospector like James ‘Philosopher’ Smith or surveyor like Charles Gould to interrupt proceedings. However, a routine of maintaining fences, preventing liver fluke in sheep, rescuing stock from bogs and patch-burning the runs left plenty of time for the hunter-stockman’s real occupation, snaring and hunting—primarily for the fur industry, secondarily for meat.

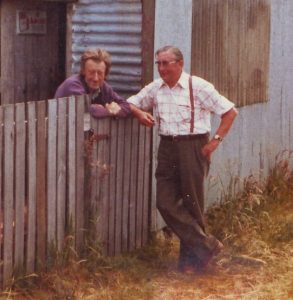

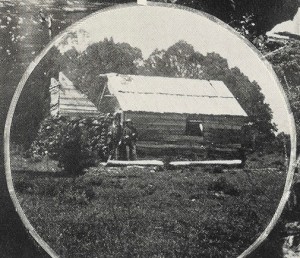

Middlesex Station, 1905, photo by RE Smith, courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Same view of Middlesex Station in 1993, 88 years on. Nic Haygarth photo.

The stock-in-trade of the highland stockman was the brush-possum-skin rug. The cold highland climate necessitated thick furs, and Francis, with his expertise in leatherworking, was well placed to take advantage of the demand for this specifically Tasmanian product.[12] Possum-skin carriage rugs and stock-whips he sold to VDL Co agent James Norton Smith fetched £2 and 16 shillings each respectively.[13] This was useful money, given that a stockman or shepherd’s annual wage was in the range of only £20–£30, supplemented by rations (flour, sugar, tea, tobacco, perhaps potatoes and some meat) delivered to a depot on Ration Tree Creek at the foot of Gads Hill, the milk he could wring from a cow, a few skilling sheep and an abundance of wallaby and wombat meat. He would have grown a few hardy vegetables, guarding them against frost and snow.

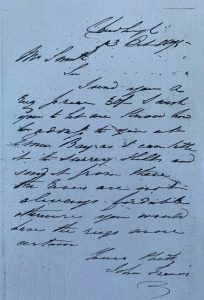

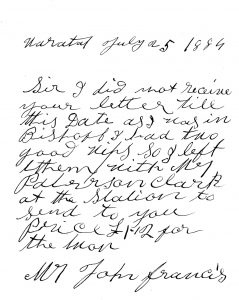

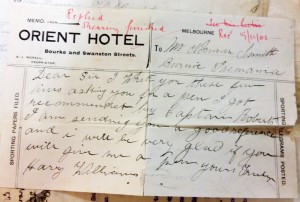

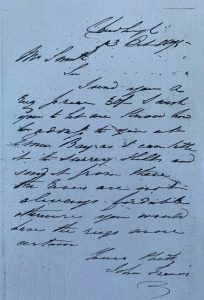

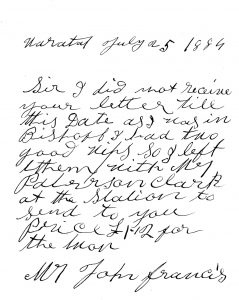

Jack Francis letters to the VDL Co’s James Norton Smith in 1875 and 1884 respectively, showing the difference between Maria’s fluent hand (above) and Jack’s laboured one (below).

From VDL22/1/9 and VDL22/1/12 (TAHO) respectively.

Not every woman would have fancied the lifestyle, but plenty of Jack’s contemporaries were accustomed to hardship. Jack Francis married 29-year-old house maid and factory worker Maria Bagwell (c1830–83) at Deloraine in 1860, subordinating his Roman Catholicism to her Protestantism.[14] She had been transported for seven years for stealing barley meal in Somerset in 1849. Perhaps she needed the nourishment, measuring only 166 cm as a nineteen-year-old. Her prison record is littered with the phrase ‘existing sentence of hard labour extended’. In 1852 she had been ‘delivered of’—deprived of?—an ‘illegitimate child’ at the Female House of Correction.[15] What happened to this unnamed girl from an unnamed father? Just as elusive is George Francis (?–1924), the child apparently born to Jack and Maria Francis during their time at Middlesex.[16]

The house maid seems to have taken to station life. In 1865 Maria Francis escorted surveyors James Calder and James Dooley from Middlesex Station to Chudleigh. To their ‘amazement’, their guide sat astride her horse like a man

‘and thus rode the whole way … with an amount of unconcern that surprised us not a little; and as if determined that we should not lose sight of this extraordinary feat of horsewomanship, she rode in front of us almost the whole distance, smoking a dirty little black pipe from one end of the journey to the other’.[17]

The couple’s son George Francis had arrived by 1871, when a child was mentioned by a visitor to Middlesex. Now Jack Francis revealed himself to be not just a skilled shoemaker and possum-skin rug maker but an expert tanner, clothing himself and his family in leather. They lived

‘in a clean and comfortable hut. A very few minutes sufficed for Mrs Francis to give us a cup of good tea, with abundance of milk, toast, and bread and butter, and when bedtime came she provided us with flealess bed-clothes, an unusual luxury in the bush….’

Jack Francis was ‘a very handy fellow … adept at shoeing a horse or drawing a tooth, having himself made a first-rate pair of forceps with which to perform this last-named operation …’ [18]

Final resting place for Jack and Maria Francis, Old Chudleigh Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

Headstone of Maria Francis, Old Chudleigh Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

Today not even a headstone in the Old Chudleigh Cemetery records this go-getter’s existence. Around Middlesex Station the ‘old’ European names are forgotten: Misery (now Courtney Hill), the Sirdar (after Horatio Herbert Kitchener of the South African War), Pilot, Sutelmans Park, Vinegar Hill, Twin Creeks. Who named them all and why? No journalist interviewed the old station hands. Yet while the Francises left their mark only in written history, digitisation of archival records is enriching our knowledge of displaced people like them, who lived remarkable lives in remote places.

[1] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[2] ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

[3] See conduct record for John Francis, transported on the Egyptian for seven years in 1839, CON31/1/12, image 175 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-12$init=CON31-1-12p175, accessed 16 February 2020.

[4] For the nickname see, for example, ‘River Don’, Weekly Examiner, 4 October 1873, p.11; ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[5] Francis’s obituarist in, for example, ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4, claimed that he was born at Woodburn, Buckinghamshire, 5 February 1828. Francis’s convict records make him a native of County Armagh.

[6] Indent for John Francis, CON14/1/48, images 25 and 26 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/tas/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fARCHIVES_DIGITISED$002f0$002fARCHIVES_DIG_DIX:CON14-1-48/one, accessed 16 February 2020. Compare, for example, his letter to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO), written by his wife Maria Francis, with his letter to James Norton Smith, 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO), written in his own hand after Maria’s death.

[7] Conduct record, as above.

[8] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[9] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[10] ‘Crown lands’, Courier, 5 February 1851, p.2; ‘Surveyor-General’s Office’, Courier, 3 December 1851, p.2; ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[11] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[12] HW Wheelright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[13] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 10 October 1873, NS22/1/4; and 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO).

[14] Married 24 December 1860, marriage record no.657/1860, at St Mark’s (Anglican) Church, Deloraine, RGD37/1/19 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages&qf=NI_NAME_FACET%09Name%09Francis%2C+John%09Francis%2C+John, accessed 15 February 2020. On his marriage certificate, Jack underestimated his age as 28 years.

[15] See conduct record for Maria Bagwell, transported on the St Vincent, CON41/1/25, image 16 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON41-1-25$init=CON41-1-25p16, accessed 15 February 2020. See also birth record for Maria Bagwell’s unnamed illegitimate female child, born 7 September 1852, birth record no.1780/1852, registered at Hobart, RGD33/1/4 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=NI_NAME%3D%22Bagwell,%20Maria%22#, accessed 15 February 2020.

[16] George Francis died 12 January 1924, will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages+%7C%7C+Deaths%09Deaths+%7C%7C+Wills%09Wills&qf=PUBDATE%09Year%091906-1976%091906-1976, accessed 16 February 2020.

[17] James Erskine Calder, ‘Notes of a journey’, Tasmanian Times, 18 May 1867, p.4.

[18] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

by Nic Haygarth | 05/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

The palm of being Waratah’s first alcoholic probably belonged to its first resident doctor, John Waldo Pring, a Crimean War veteran who drank himself to death in the years 1876–79.[1] One of his lowest moments came in March 1876 when he escorted a disguised detective to a sly grog shop for a snort.[2] Another who upset early Waratah’s temperance wagon was former Sussex labourer Charlie Drury (c1819–76), who traded native animal hides for rum. For decades before Waratah was born Drury lived a twilight existence remote from civilisation, with often only his dogs, his drink and the spirit world for companions. He even went out on a bender, leaving a legacy of decimated wildlife, delusional folklore and fire-managed grasslands to the hunters and graziers who followed him.

Mount Bischoff, Waratah, Knole Plain and the Surrey Hills. Map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Transported at 20 on a fifteen-year sentence for larceny, the 178-cm tall Drury was no mal-nourished urchin.[3] James ‘Philosopher’ Smith rather generously called him ‘a sturdy type of an Englishman’.[4] Drury could read—books and newspapers were delivered to him in the back country—although no letters survive to testify to his fluency with the pen.[5] Arriving in Van Diemen’s Land in July 1839, he went straight into the assigned service of British pastoral enterprise the Van Diemen’s Land Company (the VDL Co) at the Surrey Hills, working with hutkeeper Edward Garrett and stockkeeper Richard Lennard (c1811–94).[6] The area between the Hellyer River and Knole Plain would be his home for most of his remaining life. His early services to the VDL Co were valued at only £15 per year (when he was stationed at Emu Bay 1845–46) but rose to £30, a typical stockman’s wage of the time, in the years 1850–52.[7] Hunting would have brought in much more than that.

Drury would have been thrown out of his official work when the VDL Co shut down all operations in 1852. He attended the Victorian gold rushes in February of that year, but would have returned to his old haunts after northern graziers the Field brothers (William, John, Thomas and Charles) rented the Surrey Hills in 1853, living chiefly off the proceeds of his unfettered hunting.[8] Of course he also had the gold ‘bug’, finding a little gold at Cattley Plain under the Black Bluff Range in 1857 or 1858.[9]

The old lag was joined at the Surrey Hills by fellow ex-convict Martin Garrett (aka Garrett Martin, c1806–88), who had racked up an impressive record of robbery in Dublin, bushranging in New South Wales and probation served at Port Arthur. Not bad for a dairyman![10] Both men took to hunting, with a little prospecting on the side.[11] Like other highland hunter-stockmen such as Jack Francis of Middlesex Plains, Drury had a little cottage industry going, his specialty being the whittling of celery-top-pine walking sticks manufactured on commission.[12] It would be surprising if he didn’t also make and sell possum-skin rugs, which could fetch £2 each. The two men lived in a surprisingly sumptuous eight-room house with a blacksmith’s shop, stable, out-houses and cattle yards about two kilometres east of the Hellyer River.[13] The cottage was designed for the VDL Co by none other than onetime colonial architect John Lee Archer—something of a comedown from his work on Parliament House and the treasured Ross Bridge.[14]

Drury’s twilight zone

Decades of isolation in the boondocks of failed VDL Co settlements may have taken their toll on Drury. Even well after the tribal Aboriginal people had been driven out of the north-west, the ‘ghosts’ of their clashes with the VDL Co and the isolation played havoc with him. The company’s old Chilton homestead up above the Hellyer River was said to be haunted by the spirits of murdered Aboriginals. Drury reputedly enjoyed being lulled to sleep there by ghostly ‘music’, until one night a more lively manifestation left him crouched in the fireplace with his gun drawn.[15]

Drury sold skins to his former VDL Co workmate and ex-convict Richard Lennard, who was now keeper of the Ship Inn at Burnie. Lennard would regularly bring a horse and dray up to Drury containing grog and rations, returning to Burnie with the skins. On one occasion when Lennard was arriving at Surrey Hills, Drury came out to meet him, calling out, ‘I know what you are going to tell me—Jack Flowers is dead.’ This referred to the ex-convict known as ‘Forky Jack’, a previous workmate, who had died recently. Lennard knew that Drury had had no contact with the outside world during that time, so how could he possibly know of Flowers’ death? ‘He passed over here’, Drury told him, calling ‘Charlie [distant], Charlie [loud], Charlie [distant]’—on his way to hell.[16] James ‘Philosopher’ Smith got the same story from Drury, who had heard Flowers calling him ‘in the most hasty manner possible while very quickly passing through the air’. The hallucination, if that is what it was, apparently occurred at about the time of Flowers’ death.[17]

Drury had other supernatural experiences/hallucinations and beliefs. One day he was out hunting not far from home when it came on dark. He sat down under a tree for a nap, intending to hunt badgers (wombats) when the moon rose. He was awoken by a clap on the shoulder and the words, ‘Charlie! Didn’t you say you were going to start out after the badgers as soon as the moon was up? Here it is more than three hands high’. The speaker, Drury told his friend William Lennard, wore a sleeved waistcoat and an English top hat. Drury gathered his dogs, including Long Jim, who his new friend pointed out to him a little way off, and as he did so the apparition ‘backed away through a swamp and faded out’.[18]

On another occasion Drury and William Lennard were camped at an isolated place called Sutelmans Park somewhere near Bonds Plain (east of the Vale of Belvoir). Come morning Drury declined to leave camp, having been warned by the banshee (a female Irish spirit who heralds death) during the night that some misfortune would befall him if he did so. Lennard persuaded Drury to disregard the warning, and they went out hunting with Drury’s favourite dog Turk. Later that morning they found the dog dead. ‘There you are’, Drury remarked, ‘what did I tell you?’ Drury then tried to bring the dog back to life by ‘wailing’ over it. Lennard recalled laughing at him for being so foolish, whereupon Drury ‘levelled his gun at him and threatened to blow his head off’. Realising the precariousness of his position, Lennard quickly came to his senses.[19]

In the early 1870s Drury’s unusual ways made it into an international travel book. When an 1871 party visited the Surrey Hills, Drury fed them cold beef, and the visitors got to try those famous possum-skin rugs, which, as was customary, were alive with fleas. While his guests battled these, Drury went badger hunting by the light of the moon with about a dozen kangaroo-dogs, bringing home three skins and one entire animal—presumably for breakfast. As he explained at the dining table, ‘the morning after I have been out badger-hunting at night I always eat two pounds of meat for breakfast, to make up for the waste created by want of sleep’. Drury also recalled his pack of ferocious hunting dogs falling in with a ‘flock’ of seven ‘hyenas’, four thylacines being killed at a time when, unfortunately for him, there was no government thylacine bounty.[20]

Drury and the Bischoff tin

Through the 1850s and 1860s the VDL Co was tantalised by reports of gold discoveries on or near its land. The company’s local agent, James Norton Smith, appears to have placed some faith in Drury as a potential gold discoverer, following his claim to have found gold at the Cattley Plain, and as late as 1872 offered him prospecting tools and discussed a reward for discovery of payable gold.[21]

Prospector James ‘Philosopher’ Smith got to know Drury, calling at his cottage in December 1871 when short of food after discovering one of the world’s greatest tin lodes at Mount Bischoff. Drury had seen Smith pass by on his way to Bischoff, and now expressed surprise that he was able to stay out in the bush so long. He also told Smith that he had no food—a statement that no doubt sent a shock wave through the enervated prospector. However, relief was at hand:

‘He [Drury] replied that what he meant was that he had no beef but had kangaroo, bread and tea. He hurriedly invited me into the house and commenced to prepare a meal with the utmost celerity. He slung a camp oven containing fat and then seized a chopper with one hand and a leg of kangaroo with the other and in a few minutes he had some of the meat frying while he also attended to the tea kettle.’[22]

Smith would have found accounts of this visit written long after his death harder to swallow. In 1908 and 1923 claims were made that Smith found the Mount Bischoff tin in Drury’s hut. ‘There’s a mountain of it just outside there’, Drury apparently told Philosopher, sending him a few metres to the summit of the mountain.[23] Why anyone who had been at Waratah in its early days, when Mount Bischoff was accessed via a tunnel through the horizontal scrub, would suggest the existence of a stockman’s hut in such a position it is hard to imagine.

Drury was the stuff of which disenfranchised prospectors are made, the bumpkin shepherd who stumbles upon a fortune. The strongest argument against the Drury discovery story—apart from his stock of hallucinations—is Smith’s unblemished reputation for integrity. The closest that Drury is likely to have got to the Bischoff scrub is the very edge, where the wallabies snoozed before making their way to the grassy plains at night to feed.

Protective of his father’s reputation and achievements, Garn Smith interviewed Jesse Wiseman and William Lennard, both of whom had hunted with Drury in the early 1870s. Both said that Drury never claimed to have found the Mount Bischoff tin.[24] Wiseman recalled Drury saying, ‘Just fancy us hunting about here all these times and not knowing anything about [the Mount Bischoff tin]‘.[25]

Yet other Drury acquaintances told a different story. An anonymous source claimed that ‘old Charlie Drury made no secret about telling travellers in those days that he directed Mr James Smith to where the tin was, he having a few specimens of this strange metal in his hut, which he showed to “Philosopher” Smith, who continued the quest …’[26]

Grazier John Bailey Williams was another to vouch for Drury, telling Lou Atkinson ‘I ought to have found Bischoff as Drury told me of the mineral, but I paid no attention to him. I had heard so many wild stories of this sort’.[27] Williams had encountered Drury while trying to run sheep in the open grasslands at Knole Plain in 1864–65.[28] His application to lease 6500 acres of Crown land there foundered, with many sheep reportedly starving to death.[29] Well might he have wished for a tinstone saviour!

However, it seems that wild stories were Drury’s stock in trade. It wouldn’t be at all surprising if the old sot had mineral samples in his hut—but it would be a great shock if they were cassiterite specimens.[30]

Opportunity knocks

The Mount Bischoff Tin Mine and its new trade route with Emu Bay brought financial opportunity to previously remote hunter-stockmen. Fields’ Hampshire Hills overseer Harry Shaw wanted to set up an ‘eating house’ along the road. [31] Garrett must have had similar commerce in mind when he tried to buy land at the Hampshire Hills.[32] He later drove the VDL Co Tram between Emu Bay and Bischoff and worked as a blacksmith at the Wheal Bischoff Co Mine.[33] Drury became a commercial operator. He and his mate John Edmunds established a base on the hunting ground of Knole Plain, leaving Garrett to hunt the Surrey Hills. Their hut stood right along the track to the mountain, on grasslands that the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company wanted to keep for feed for the bullock and horse teams carting between Waratah and the port at Emu Bay. They were professional hunters paying a £1 annual licence and returning up to £70 per season for shooting 600 to 1000 wallabies as well as the brush possums which formed their possum-skin rugs—at least that was told they told a visiting reporter.[34] The suggestion that such men obeyed government regulations is ludicrous. Additional money was to be had packing supplies for mining companies, as well as supplying Waratah with wallaby meat and some of the grog that they received from Emu Bay.[35] Feeding 20 kangaroo dogs alone would necessitate constant hunting.

Mount Bischoff from Knole Plain, 2009. Nic Haygarth photo.

The new trade route through to Emu Bay also gave hunters like Drury and Garrett better access to skin buyers—although their attempt to sell the skins of Drury’s beloved badger seems to have foundered. [36] While Garrett and Drury were out hunting, their charges—the Field brothers’ notoriously wandering cattle—wandered onto Waratah dinner plates, much to their owners’ disgust. In 1874 Thomas Field called for police intervention.

So did the Mount Bischoff Company when the first pub opened in town.[37] Drury’s unofficial pub never closed. One man was discharged from Walker and Beecraft’s tin claim for getting drunk there.[38] Drury himself was likely to get ‘on the spree’ at any time, making him an unreliable employee.[39] There was a celebrated incident in which Drury got hammered on a keg of rum and accidentally burned down his and Edmunds’ hut, destroying not only his own skins and stores but supplies belonging to prospectors Orr and Lempriere and surveyor Charles Sprent. The only thing salvaged was the keg, to which the hunter was said to have clung ‘with the affection of a miser’.[40]

Drink eventually killed Drury in his hut at Knole Plain. James Smith learned that:

‘His end was a melancholy one. He had been drinking somewhat heavily when two Christian men from Waratah went to see him at his hut … While talking to his new friends he lay down on his bed and seemed to doze but when after a time one of them tried to rouse him it was found that he was dead.’[41]

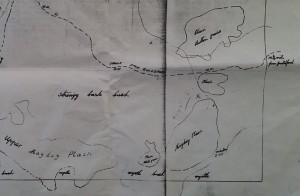

Detail from Charles Sprent’s January 1874 map, ‘Plan of agricultural sections on Knole Plain, County of Russell’, showing ‘hut and kennels’ (upper right, just above the road reserve. AF396/1/806 (TAHO).

Potential rubble from Drury’s hut protruding from the furrows of a future plantation on Knole Plain in 2009. Presumably Drury remains buried here, although the eucalypt that marked the spot is long gone. Nic Haygarth photo.

Finding Drury

Drury is said to have been buried beneath a eucalypt near his hut on Knole Plain.[42] Did anything remain there of either his hut or his grave? Examining an old map of Knole Plain more than a decade ago, Burnie surveyor and historian Brian Rollins found the notation ‘hut and kennels’. Brian was interested to find a James Sprent survey cairn that was marked on the same map. We resolved to combine our interests and, under the stewardship of Robert Onfray from Gunns, we made a trip to the Knole Plain area. We found ploughed remains of a long-fallen building which suggested Drury’s hut or some later version of it. No weathered cross tilted over the detritus. No bleached bones poked out of the furrows of the plantation coup. Perhaps Charlie Drury is six feet under the tussock grass, raising a toast with his insubstantial friends, his beloved dogs crashing through some underworld after twilit kangaroo, badger and tiger.

[1] ‘Mount Bischoff’, Devon Herald, 27 September 1879, p.2; he died of natural causes, 19 September 1879, inquest SC195/1/60/8154 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, afterwards TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-60-8154, accessed 29 February 2020.

[2] ‘Sly grog selling at Mount Bischoff, Cornwall Chronicle, 27 March 1876, p.3.

[3] Drury was transported on the Marquis of Hastings. See his conduct record, CON31/1/12, image 31 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-12$init=CON31-1-12p31, accessed 1 March 2020, also Description list, CON18/1/16, p.200 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=drury#, accessed 23 February 2020.

[4] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO).

[5] Cavanagh (?) to James Smith, 24 January 1875, no.38, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[6] VDL61/1/2 (TAHO). For Lennard see conduct record, CON31/1/27, image 179 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-27$init=CON31-1-27p179, accessed 1 March 2020.

[7] VDL133/1/1 (TAHO).

[8] From Launceston to Melbourne on the City of Melbourne, 3 February 1852, POL220/1/1, p.558 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=drury#, accessed 23 February 2020. Drury’s sentence expired in March 1853, leaving him free to choose his employer (‘Convict Department’, Launceston Examiner, 19 March 1853, p.6).

[9] See WR Bell, ‘Report on the hydraulic gold workings at Lower Mayday Plain …’, 14 May 1896, EBR13/1/2 (TAHO). In June 1858 a prospector W MacNab testing the Hampshire and Surrey Hills for gold complained that a mining cradle he expected to use had been removed for use by a stockkeeper from the Surrey Hills Station. See W MacNab to James Gibson, VDL Co agent, 9 June 1858, VDL22/1/2 (TAHO).

[10] See his conduct record, CON39/1/2, p.334 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=Martin&qu=garrett, accessed 23 February 2020. After a stint in the New Town Invalid Depot (admitted 24 November 1886 to 17 December 1886, POL709/1/21, p.207) Garrett died of ‘dropsy’ (oedema, fluid retention) in Launceston in 1888 when he was said to be 82 years old (2 December 1888, death record no.391/1888, registered in Launceston, RGD35/1/57 [TAHO]).

[11] Garrett may have discovered the barytes deposit at the Two Hummocks near Fields’ Thompsons Park Station (James Smith to Ritchie and Parker, 10 July 1875, no.327, VDL22/1/4 [TAHO]).

[12] Richard Hilder, ‘The good old days’, Advocate, 5 January 1925, p.4; Charles Drury to James Norton Smith, 24 July 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[13] ‘Country news’, Tasmanian, 30 August 1873, p.5; G Priestley, ‘Search for Mr D Landale’, Weekly Examiner, 11 October 1873, p.19.

[14] Agreement between the VDL Co and builder George Fann, 4 March 1851, VDL19/1/1 (TAHO). Fann was paid £150 for the job on 19 April 1852 (VDL133/1/1, p.153 [TAHO]). Archer sent two designs for a stockkeeper’s hut to James Gibson on 17 February 1851, although unfortunately the designs cannot be found on file (VDL34/1/1, Personal letters received by James Gibson [TAHO]). See also the 1842 census record for Richard Lennard, who was then living at the VDL Co’s old Chilton homestead. He was one of ten men from the ages of 21 to 45 resident there at the time, only one of whom arrived in the colony free, while another qualified under ‘other free persons’. Two who were in ‘government employment, six in ‘private assignment’. Two were ‘mechanics or artificers’, two were ‘shepherds or others in the care of sheep’, five were ‘gardeners, stockmen or persons employed in agriculture’ and one was a ‘domestic servant’ (CEN1/1/8, Circular Head, p.63 [TAHO], https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=richard&qu=lennard, accessed 1 March 2020).

[15] William Lennard, quote by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’, RS Sanderson to Arch Meston, May 1923?, M53/3/6 (Meston Papers, University of Tasmania Archives, Hobart).

[16] William Lennard, quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[17] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO).

[18] William Lennard, quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[19] William Lennard, quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[20] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

[21] James Norton Smith to VDL Co Court of Directors, Outward Despatch 38, 15 May 1872, p.482, VDL1/1/6; James Norton Smith to Charles Drury, 12 June 1872, p.493, VDL7/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO).

[23] ‘Patsey’ Robinson, quoted in ‘The oldest inhabitants’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 April 1908, p.2.

[24] GH Smith, ‘The true story of Bischoff’, Advocate, 1 May 1923, p.6.

[25] Jesse Wiseman quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[26] ‘1866’, ‘Discovery of tin at Mount Bischoff’, Advocate, 30 April 1923, p.6.

[27] John Bailey Williams, quoted by RS Sanderson, Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[28] John Bailey Williams to Charles H Smith, Du Croz & Co, 25 January 1865; and to VDL Co agent Charles Nichols, 11 April 1865, VDL22/1/3 (TAHO).

[29] Thomas Barrett to R Symmons, 2 March 1867, VDL22/1/3 (TAHO).

[30][30] Thomas Broad claimed to have seen tin specimens in Drury’s hut—but did Broad have enough expertise in mineralogy to make that call? See Thomas Broad, ‘Mt Bischoff’s early days’, Advocate, 3 May 1923, p.2.

[31] James Smith to Ferd Kayser, 15 January 1876, NS234/2/1/2 (TAHO).

[32] James Smith to Martin Garrett, 30 June 1875, no.310, NS234/2/1/2 (TAHO).

[33] Hugh Lynch to James Norton Smith, 23 April 1877, VDL22/1/5; Daniel Shine to James Norton Smith, 27 October 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[34] ‘Country news’, Tasmanian, 30 August 1873, p.5.

[35] For packing, see WR Bell to James Smith, 20 July 1875, no.335; and Joseph Harman to James Smith, 11 October 1875, no.450, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[36] AM Walker to James Smith, 11 February 1873, no.115, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO).

[37] Minutes of directors’ meetings, Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company, 7 September 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[38] Mary Jane Love to James Smith, 12 October 1873, no.290/291, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO).

[39] William Ritchie to James Smith, 9 March 1874, NS234/3/1/3 (TAHO).

[40] ‘Trip to Mount Bischoff’, Mercury, 18 December 1873, p.3.

[41] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO). Drury died 3 March 1876, death record no.151/1876, registered at Emu Bay, RGD35/1/45 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=drury#, accessed 23 February 2020. Cause of death was given as ‘excessive drinking’.

[42] ‘An Old Hand’, ‘The O’Malley and the Labor Movement in Tasmania’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 28 May 1908, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 08/12/18 | Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

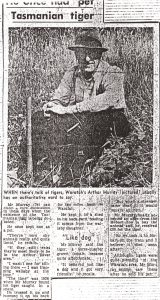

Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray reckoned that thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) followed him when he walked from Magnet to Waratah in the state’s far north-west—out of curiosity, rather than malicious intent. If he swung around suddenly he could catch a glimpse of one.[1] However, Cutter did better than that. In 1925 he caught a tiger alive and took it for a train ride to Hobart.

Tigers are just one element of the twentieth-century tale of Cutter and his elder brother Basil Murray. Yet for all their exploits these great high country bushmen started in poverty and rarely glimpsed anything better. Cutter married and produced a family, but his weakness all his working life was gambling: what he made on the possums (and tiger) he lost on the horses. Basil made enough money to keep the taxman guessing but was content to live out his days in a caravan behind Waratah’s Bischoff Hotel.[2]

Their ancestry was Irish Roman Catholic. Basil Francis Murray (1893–1971) was born to Emu Bay Railway ganger Edward James (Ted) Murray and Martha Anne Sutton. He was the couple’s ninth child. Arthur Royden Murray (1898–1987?) was the twelfth.[3] Three more kids followed. The family lived at the fettlers’ cottages at the Fourteen Mile south of Ridgley while Ted Murray was a ganger, but in 1907 he became a bush farmer at Guildford, renting land from the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co).[4] Guildford, the junction of the main Emu Bay Railway line to Zeehan and the branch line to Waratah, had a station, licensed bar and state school, but was also a centre for railway workers, VDL Co timber cutters and hunters. Edward Brown, the so-called ‘Squire of Guildford’, dominated local activity.

Guildford Junction State School, with teacher May Wells at centre. From the Weekly Courier, 10 November 1906, p.24.

Squaring sleepers, splitting timber, hunting, fencing, scrubbing out bush, driving bullocks, herding stock, milking cows and setting snares were essential skills for a young man in this locality. Like others, the Murrays snared adjoining VDL Co land, paying the company a royalty. Several Murray boys escaped Guildford by serving in World War One, but Cutter recalled that his father would not let him enlist.[5] Basil also stayed home.[6] Perhaps it was enough for Ted and Martha Murray that they lost one son, Albert Murray, killed in action in France in 1916.[7]

Guildford Railway Station during the ‘great snow’, 1921. Winter photo, Weekly Courier, 18 August 1921, p.17.

Guildford Station under snow again, 24 September 1930. RE Smith photo, courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Twenty-three-year-old Arthur Murray appears to have married Alice Randall in Waratah during the ‘great snow’ of August 1921. He would already have been a proficient bushman. Cutter learned to use the treadle snare with a springer, although he would also employ a pole snare for brush possum and would shoot ringtails. He shot at night using acetylene light to illuminate the nocturnal ringtails, but he found it easier to go after them by day by poking their nests in the tea-tree scrub. ‘It was like shooting fish in a barrel’, Cutter’s son Barry Murray recalled. ‘It was only shooting as high as the ceiling … A little spar and you just shook it … and they’d come out, generally two, a male and a female …’[8] Hunters aimed for the nose so as to keep the valuable fur untainted.

In the bush Cutter lived so roughly that no one would work with him. Some tried, but none of them lasted. His huts and skin sheds on the Surrey Hills were little more than a few slabs of bark. Friday was bath day, which meant a walk in Williams Creek (east of the old Waratah Cemetery), regardless of weather conditions. Cutter’s son Val once snared Knole Plain with him, but couldn’t keep up. Snares had to be inspected every day, the game removed, and the snares reset. Cutter and Val took snaring runs on opposite sides of the plain, but Val found that even if he ran the whole way and didn’t reset any snares, Cutter would be sitting waiting for him, having long completed his side.

Cutter’s most substantial skin shed was near home base, on the hill above the primary school at Waratah. Here he would smoke the skins before an open fire. He pegged them out both on the wall and on planks about eighteen inches wide, each plank long enough to accommodate three wallaby skins. When the sun shone, he took the laden planks outside; otherwise he sat inside the skin shed with his skins, chain smoking cigarettes in empathy. A skin shed had no chimney, the idea being that the smoke would brown the skins as it escaped through the cracks between the planks of the walls. The air was so black with smoke that Cutter was virtually invisible from the doorway.[9] Yet no carcinogens prevented him reaching his eighties.

Joe Fagan claimed that Basil Murray was such a good snarer that he once snared Bass Strait.[10] Basil preferred the simple necker snare to the treadle, and caught a tiger in such a device on Murrays Plain, a little plain above the 40 Mile mark on the railway named after Ted Murray.[11] Cutter caught a couple of three-quarters-grown tigers. One was taken dead in a treadle snare with a springer on Goderich Plain when Cutter was hunting with Joe Fagan.[12] Joe kept the skin for years as a rug, but when it grew moth-eaten he tossed it on the fire—oblivious to its rarity or future value.[13] Cutter caught the other thylacine alive in a treadle near Parrawe.[14] He trussed her up and humped her home, where ‘a terrific number of people’ came for a look.[15] ‘They’re very shy animals really, and quite timid’, he recalled of the captive female. ‘It behaved just like a dog and it got very friendly. But when a stranger came near it would squark at them.’[16] At first he couldn’t get her to eat. The breakthrough came when he skinned a freshly caught wallaby, rolled the carcase up in the skin with the fur on the inside, and fed it to the tiger while it was still warm.[17] In June 1925 ‘Murray bros, Waratah’ advertised a ‘Tasmanian Tiger (female)’ in the ‘For sale’ columns of the Examiner and Mercury newspapers.[18] Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo offered £30 for it, prompting Cutter to deliver her by train. It was his only visit to Hobart. Four cruisers of the American fleet were in town, and Cutter recalled that ‘it was so crowded you could hardly move. I didn’t like it much’.[19]

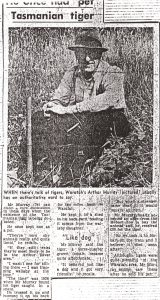

Cutter tells his story, Mercury, 13 February 1973, p.12.

The other big event in Hobart at the time was the Adamsfield osmiridium rush, which ensnared Basil Murray. In the last quarter of 1925 he pocketed £126 from osmiridium, the equivalent of a year’s wage for a farmhand.[20] Later he spent six months mining a tin show alone at the Interview River. Having set the exact date he wanted to be picked up by boat at the Pieman River heads, Basil hauled out a ton of tin ore on his back, bit by bit.[21] On another occasion he worked a little gold show on the Heazlewood River, curling the bark of gum saplings to make a flume in order to bring water to the site.[22]

It was pulpwood cutting that gave Arthur Murray his nickname. When Associated Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) started manufacturing paper at Burnie in 1938, it turned to Jack and Bern Fidler of Burnie company Forest Supplies Pty Ltd for pulpwood.[23] Over the next two decades Joe Fagan supplied about one-third of the pulpwood quota as a sub-contractor to the Fidlers. At a time when Mount Bischoff was a marginal provider for a few families, and osmiridium mining had fizzled out, Fagan became a significant employer, with about 65 men splitting barking and carting cordwood to the railway at Guildford for transport to Burnie.[24]

A good splitter would split about 3 cords of wood (a cord equals 128 cubic feet of timber) per day. Cutter held the record for the best daily effort, 8½ cords. Unlike most splitters, he never used an axe, but wedged off and split the billet into three pieces. Yet Cutter’s pulpwood stacking exasperated Joe Fagan. Unlike other men, Cutter did not stack his pulpwood as he went. Pulpwood cutters were paid according to the size of their stacks, and the large gaps in Cutter’s hasty, last-minute efforts ensured that he got paid for a bit more fresh air than he was entitled to. Kicking one such stack, Joe growled:

‘I don’t mind the rabbits goin’ through, Arthur, but I bloody well hate those bloody greyhounds behind them goin’ through the holes’.[25]

World War Two was a lucrative time for snarers. £15,000-worth of skins were auctioned at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, while more than 32,000 skins were offered there in the following year. Record prices were paid at what was probably the last annual Guildford sale in 1946.[26] Taking advantage of high demand, the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue. One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins as its seasonal haul.[27]

Both Murrays cashed in. Cutter made £600 one season.[28] Working with Eric Saddington at the Racecourse, Surrey Hills, Basil took 3000 wallabies in 1943. Unfortunately their wallaby snares also landed 42 out-of-season brush possums (21 grey and 21 black)—which landed the pair in court on unlawful possession charges. Both men were fined.[29] Basil had a reputation for being a ‘poacher’, and one story of his cunning, apocryphal or not, rivals those told about fellow poacher Bert Nichols.[30]

According to Ted Crisp, Basil was sitting at the bar at the Guildford Junction Railway Station when two Fauna Board rangers came in on the train and announced they were looking for Basil Murray, whom they believed had a stash of out-of-season skins. Then they set off for his hut, rejoining the train to go further down the line:

‘Old Baz headed down by foot and took after them, he was a pretty good mover in the bush and the trains weren’t real fast … and by the time he got down there, they’d found his skins, decided there were too many to carry out so they’d hide them and pick them up at a later date, and of course old Baz was sitting there watching them, they had to catch the train back a couple of hours later, they left and old Baz picked up the skins and moved them to another place …’

By the time the Fauna Board rangers got back to Guildford, Basil was still in the bar, propped up against the counter.[31] However, the taxman did better than the Fauna Board rangers. Basil seems to have been a chronic tax avoider. He and Eric Saddington were camped at Bulgobac, squaring sleepers and snaring, when they were busted for not filing tax returns for the years 1941–42–43.[32]

Basil kept on in the same vein, landing a £25 fine for not lodging a 1943–44 return and then a whopping £60 for the 1947–48–49 period.[33] Things finally got too hot for Basil, who adjourned to the Victorian goldfields for a time.[34]

In 1951 Basil was the cook for the party re-establishing the track between Corinna and Zeehan. One of the track-makers, Basil’s nephew Barry Murray remembered him as ‘a good old cook, as clean as Cutter was rough. They were just opposites. He had a big Huon pine table. He used to scrub it with sandsoap every day, and he would have worn it away if he’d stopped there for two or three years’.[35] Basil became well known as APPM’s gatekeeper at the Hampshire Hills.

In 1963 Cutter Murray was one of Joe Fagan’s men recruited by Harry Fraser of Aberfoyle in a party which investigated the old Cleveland tin and tungsten mine and recut the Yellowband Plain track to Mount Lindsay. At the party’s Mount Lindsay camp Cutter used snares to reduce the numbers of marauding devils that were tearing through the canvas tents, biting the tops off sauce bottles and biting open tins of beef and jam.[36]

Cutter Murray (left) and friend at Waratah. Note the Ascot cigarettes advertisement on the wall behind him. Photo courtesy of Young Joe Fagan.

Cutter snared until virtually the day he died in the 1980s, making him—along with Basil Steers—one of the last of the snarers. He possumed on North’s block and took wallabies on the Don Hill, under Mount Bischoff, wheeling the skins home draped over a bicycle. A great snaring dog, a labrador that he had trained to corner but not kill escaped game, made his life easier.[37] Nothing is known to remain of his hunting regime, not a hut or a skin shed. Barely a photo remains of the hardy bushman. His tiger tale flitted across the country via newspaper in 1984, then was forgotten.

Unfortunately Cutter Murray’s travelling tiger has an equally obscure legacy, apparently dying soon after it was received at the Beaumaris Zoo.[38]

[1] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[2] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[3] Registration no.484, born 16 May 1898, RGD33/1/85 (TAHO). Basil Murray’s years of birth and dirt are recorded on his headstone in the Wivenhoe General Cemetery, Burnie.

[4] ‘Ridgley’, North West Post, 8 October 1907, p.2.

[5] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’, Australian, 1984, publication details unknown.

[6] Basil and John Murray were refused an exemption (‘Waratah Exemption Court’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 November 1916, p.2; ‘Burnie: in freedom’s cause’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 13 January 1916, p.2), but there is no record of Basil serving.

[7] ‘Tasmanian casualties’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 22 September 1916, p.3.

[8] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[9] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[10] Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[11] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[12] Cutter Murray and Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[13] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, the author, Somerset, 1994, pp.62–66.

[14] Cutter Murray and Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[15] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’, Australian, 1984, publication details unknown.

[16] Cutter Murray; quoted in ‘He once had pet Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 13 February 1973.

[17] AAC (Bert) Mason, No two the same: an autobiographical social and mining history 1914–1992 on the life and times of a mining engineer, Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Hawthorn, Vic, 1994, p.571.

[18] See, for example, ‘For sale’, Examiner, 17 Jun 1925, p.8.

[19] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’.

[20] Register of osmiridium buyers’ return of purchases, MIN150/1/1 (TAHO).

[21] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[22] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[23] Steve Scott, quoted by Tess Lawrence, A whitebait and a bloody scone: an anecdotal history of APPM, Jezebel Press, Melbourne, 1986, p.25.

[24] Kerry Pink, ‘His heart belongs to Waratah … Joe Fagan’, Advocate, 10 August 1985, p.6.

[25] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[26] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4; ‘Over 32,000 skins offered at sale’, Advocate, 13 September 1944, p.5; ‘Record prices at Guildford skin sale’, Advocate, 30 July 1946, p.6.

[27] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4.

[28] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[29] ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[30] For Nichols’ poaching, see Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.116–19.

[31] Ted Crisp; quoted by Tess Lawrence, A whitebait and a bloody scone: an anecdotal history of APPM, p.26.

[32] ‘Men fined’, Mercury, 5 May 1944, p.6.

[33] ‘Fines imposed for income tax offences’, Mercury, 5 September 1946, p.10; ‘Fined for tax breaches’, Examiner, 6 July 1950, p.3.

[34] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[35] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[36] AAC (Bert) Mason, No two the same, pp.570–71, 577, 579.

[37] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[38] Email from Dr Stephen Sleightholme 26 December 2018; Cutter Murray stated his belief that it died soon after arrival in Hobart in ‘He once had pet Tasmanian tiger’. I thank Stephen Sleightholme and Gareth Linnard for their contributions to this story.

by Nic Haygarth | 20/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

Ever felt the need to turn the orthodox version of history on its head, and look at it upside down? Sometimes I want to write history from the ground up, from the perspective of people at the bottom of the food chain. With that in mind, I once set out to try to prove that the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) was primarily a fur farmer during its first century, that is, that more money was generated by the culling of marsupials on its land than by grazing and agriculture. Unfortunately, there are few surviving records of the skins sales of disparate hunter-stockmen employed by the company, making the task very difficult.

That the VDL Co learned to exploit the fur trade emphasises that the company’s survival for nearly 200 years has pivoted on its flexibility. When wool-growing failed, it withdrew, leased its lands and waited for the right time to return as a wool, dairy, beef, timber and brick producer. When it could find no minerals on its lands, it built a port and established a railway so that it could exploit other people’s mineral exports. It sold its land and its timber. When the fur trade peaked in the 1920s it exploited that. Now it is referred to as Australia’s biggest dairy farmer. Is high-end heritage tourism or Chinese niche tourism the next chapter in the story of Woolnorth, the VDL Co’s remaining property?

Just to rewind a little, the hunter-stockmen who worked the VDL Co’s land had always exploited the fur trade. It was part of their employment obligations: we pay you a small wage, thus giving you the incentive to increase your income by killing all the grass-eating marsupials and all potential predators (tigers, wild dogs and eagles) of sheep, and thereby conferring a mutual benefit. You sell the marsupial skins, and we will even throw in a bounty for every predator you kill.

The killing of predators represented a bonus for hunter-stockmen whose main game was killing wallabies, pademelons and possums. By 1830 thylacines were being blamed for killing the company’s sheep, although it is clear that poor pasture selection and wild dogs were bigger problems. After the catastrophic loss of 3674 sheep at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills in the years 1831–33 to severe weather conditions and the attacks of wild animals, it was decided to temporarily cease grazing sheep there, transferring that stock to Circular Head and Woolnorth.[1] In 1830 a £1 bounty was offered for the killing of a particular thylacine at Woolnorth.[2] From 1831 the VDL Co paid a regular reward for killing thylacines on its properties, initially 8 shillings, later 10.[3] The Court of Directors in London seemed to panic about the company’s prospects, stating that ‘We fear the hyenas and wild dogs, more than climate’.[4] The dilemma of the dog problem is clear. Requests for a thylacine-killing dog for Woolnorth were matched by reports of sheep depredations of dogs belonging to Woolnorth servants.[5] In 1835–37 the VDL Co employed a dedicated ‘pest controller’, James Lucas, to kill wild dogs and thylacines at first at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, then at Woolnorth.[6] Lucas, a ticket-of-leave convict, could be said to have been the first Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, although he was never referred to by that name and was employed there only briefly.[7] He operated on the same thylacine bounty of half a guinea. Whether due to Lucas’ performance or other influences, stock losses at Woolnorth dropped dramatically during his time there and the panic over thylacines and wild dogs subsided. However, bounty payments for the killing of predators had been resumed by 1850, as the following table illustrates:

Rewards paid by the VDL Co for the killing of predators at Woolnorth 1850–51

| Name |

Time |

Program |

Kill |

Payment |

| Edward Marsh |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena |

5 shillings |

| A Walker |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Two hyenas |

10 shillings |

| Richard Molds |

Aug 1850 |

Cross bred Leicester sheep |

Three dogs |

15 shillings[8] |

| A Walker |

Nov 1850 |

Improved sheep |

Hyena |

£1-2-11[9] |

| Richard Molds |

Feb 1851 |

Leicester sheep |

Dog |

5 shillings[10] |

| A Walker |

Sep 1851 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena & Two Eagle Hawks |

4 shillings 6d[11] |

| W Procter |

Dec 1851 |

Woolnorth |

Hyenas |

10 shillings[12] |

VDL Co withdrawal and the Field brothers on the Surrey Hills

In 1852 the VDL Co withdrew from Van Diemen’s Land, becoming an absentee landlord and, by 1858, its Hampshire and Surrey Hills and Middlesex Plains blocks were all leased to the Field family graziers. Tasmanian furs were already renowned, even before a market was found for them in London. Tasmanian bushmen and excursionists favoured possum-skin rugs as bedding. The best brush possum rugs to be had in Melbourne were reputedly those made by Tasmanian shepherds from snared skins, where the animals grew larger and more handsome than their Victorian counterparts.[13]

Fields’ outposted hunter-stockmen invariably hunted for meat, skins and clothing, burning off the surrounding scrub and grasslands to attract game. When an 1871 party visited the Hampshire Hills station, the peg-legged Jemmy, who was the designated cook, whipped up wallaby steaks. At the Surrey Hills, Charlie Drury, a delusional ex-convict hunter-stockman whom Fields inherited from the VDL Co, fed them cold beef, and the visitors got to try those famous possum-skin rugs, which, as was customary, were alive with fleas. While his guests battled these, Drury went ‘badger’ (wombat) hunting by the light of the moon with about a dozen kangaroo-dogs, bringing home three skins and one entire animal—presumably for breakfast. As he explained at the dining table, ‘the morning after I have been out badger-hunting at night I always eat two pounds of meat for breakfast, to make up for the waste created by want of sleep’. Travelling further, the party found that Jack Francis, stockman at Middlesex Plains, made his family’s boots and shoes from tanned hides. He also tanned brush possum skins for rugs, which again formed the bedding—flealessly this time.[14]

Records of hunter-stockman sales of skins from this period are scant. A rare example is an account in the VDL Co papers of its Mount Cameron West ‘tigerman’ William Forward sending 180 wallaby and 84 pademelon skins to market in April 1879.[15] In 1879 the open season for ‘kangaroo’ (wallaby) was from 31 January to 31 July, suggesting that Forward’s haul represented at most two months’ worth out of a six-month season.[16] By market prices of the time these skins would have been worth at least £8–4–0 and at most £14–14–0. If we assume that his haul for the six-month season was three times as much, we can imagine him earning at least as much as his annual wage of £20–£30. And that is without bonuses for thylacine killings.

Luke Etchell, career bushman

While Charlie Drury was drinking himself to death at his hunting hut on Knole Plain, and the VDL Co plotting the removal of Fields and all their wild cattle from the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, Luke Etchell was a child growing up fast. He was the son of John Etchell or Etchels, a transported ex-convict harking from rural Lancashire. How many of the sins of the father were visited on the son? By the time of his transportation at the age of fifteen, John Etchell had already racked up convictions for housebreaking, theft, assault and, perhaps most telling of all, vagrancy. He was illiterate.[17] While still a convict in Van Diemen’s Land, he twice saved someone from drowning. [18] However, the negative side of the ledger kept him in the convict system. Christopher Matthew Mark Luke Etchell—a child with most of the Gospels and more—was born to John and Mary Ann Etchell, née Galvin, at Stanley, on 17 December 1868, as perhaps their fourth child.[19] (The origins of Mary Ann Galvin or Galvan have so far proven elusive.[20]) His family lived in a hut at Brickmakers Bay which was destroyed by fire in 1874, then appears to have moved to Black River, at a time when payable tin had been found at Mount Bischoff and specks of gold in west- and north-flowing rivers.[21] John Etchell worked as a labourer, a paling splitter and a prospector who claimed to have found gold eighteen km south-east of Circular Head in 1878.[22]

Life was not harmonious or easy, however, as suggested by Mary Ann Etchell’s successful application for a protection order against her husband in August 1880. In the court proceedings she alleged that about a year earlier he had threatened to sell everything in order to raise money to get him to Melbourne, where she supposed he was now. For the last five months all he had contributed for the upkeep of his family was 228 lb (103 kg) of flour and one bag of potatoes. [23] It seems that the family never saw John Etchell again and, given the request for a protection order, they were probably glad about it.

Certainly Luke Etchell became self-reliant very quickly. He claimed that at the age of nine, that is, in 1877, he was already working in a tin mine on Mount Bischoff and at one of the stamper batteries at the Waratah Falls, and it is true that, almost in the Cornish tradition, young boys found mining work of this kind.[24] (One of his contemporaries as a bushman, William Aylett, born in 1863, claimed to have been learning how to dress tin at Bischoff at the age of thirteen in 1876.[25]) His English-born relative John Wesley Etchell was certainly established in Waratah by December 1878, operating a shop owned by the ubiquitous west coaster JJ Gaffney, and the family made the move there, presumably with John Wesley Etchell as the major breadwinner. [26] Luke, like some of his brothers and sisters, had at least one brush with the law in his youth.[27]

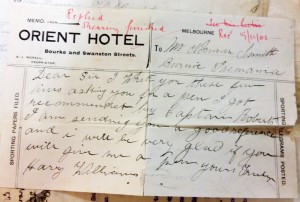

Even ‘Black’ Harry Williams the tiger killer needed to go shearing for additional income. Here he asks the VLD Co for a shearing pen in 1901. From VDL22-1-31 (TAHO).

Etchell was probably with his family at Waratah until at least 1886, when he was eighteen. Over the next two decades he became an expert bushman, apparently commanding familiarity with all the country between the lower Pieman River and Cradle Mountain.[28] His base was at Guildford Junction, the village centred on the junction of the VDL Co’s lines to Waratah and Zeehan, on the hunting territory of the Surrey Hills. He also became handy with his fists, featuring in a public boxing match in 1902.[29] Other hunters, successors to Drury, were working the Surrey and Hampshire Hills. By 1900 ‘Black’ Harry Williams, for example, the ‘colored [sic] king of the forest’, was building a reputation as a tiger tamer on the Hampshire Hills, even showing a live one in Burnie which he intended to sell to Wirth’s Circus.[30] Williams probably collected four government thylacine bounties, whereas Etchell collected only one, in 1903, most of his incidental tiger kills coming after the bounty was abolished.[31]

In 1910 ‘Tasmanian Chinchilla (clear blue Australian possum)’ took its place in the American fur catalogue alongside Hudson seal, skunk, beaver, wolf and chamois. Advert from the Chicago Daily Tribune, 17 December 1910, p.26

By 1905 Etchell was sufficiently well known as a bushman of the high country to be recommended as the man to lead a search for Bert Hanson, the seventeen-year-old lost in a blizzard on the eastern side of Dove Lake.[32] Making a living as a bushman meant grasping every opportunity that came along, be it splitting palings, cutting railway sleepers, taking a contract to build or repair a road or working an osmiridium claim. In 1910, for example, Etchell’s £30 tender for work on the road at Bunkers Hill was accepted by the Waratah Council.[33] In 1912 he obtained a tanner’s licence, suggesting that he intended to deal in skins.[34]

‘X’ marks the spot. The Etchell Mayday (First of May) Plain hut raided by police in 1937 in the south-western corner of the Surrey Hills block. Note also the prospectors’ camp marked nearby. From AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

However, it was as a snarer that Etchell made his reputation. He would have learned how to hunt as a boy from his father or brothers. Like the Ayletts, the Etchell family dealt extensively in the fur trade. Luke’s brother William snared and bought skins.[35] His cousin Harold Reuben Etchell had run-ins with the law over skin dealings, being the subject of a police stake-out and raid on a hut on the Mayday Plain (now First of May Plain).[36] Ernest James Etchell was another hunter who tested or blurred the hunting regulations.[37] However, Luke struck up a partnership with his brother Thomas, who also dabbled in prospecting.[38]

Atkinson’s hut and skin shed at Thompsons Park, on the Surrey Hills block. Thompsons Park was the site of a Field brothers’ stock hut. Later it also served seasonal hunters.

The pile of rubble or huge chimney butt beside Atkinson’s hut from a previous building on the Thompsons Park site.

As outlined previously, having hunters remove the plentiful game from its remaining land benefited the VDL Co stock—and the company gained doubly by charging these men for the privilege. The VDL Co engaged Surrey Hills hunters on a royalty system of one-sixth of their skins taken. In February 1912, for example, its Guildford man Edward Brown told its Tasmanian agent AK McGaw that Thomas Etchell had requested a run near the Fossey River, whereas R Brown wanted the 31 Mile or the West Down Plain (which turned out to be outside the Surrey Hills boundary). ‘I have told them that they must report to me before sending any of their skins away’, he wrote, ‘so I can count them and retain two out of every dozen for the company …’ [39] The disadvantage of this system for the VDL Co was that hunters could cheat, and later that season Brown claimed that DC Atkinson and Luke Etchell were not submitting all their skins to him from a lease Atkinson had taken on ‘the Park’. Brown found particular fault with their second load of skins:

‘The next lot was over 1½ cwt and Etchell gave me 11 which weighed 8 lbs and said “that was his share” but Atkinson would not give any as he caught them on his own ground. I know for sure he as [sic] snares set other than on his own ground. I think he was given the right on the conditions he gave 2 in the dozen regardless of where they were caught. Anyhow Atkinson should have given 11 and that would leave about ½ cwt to come off his own ground …’[40]

Ironically, the Animals and Birds Protection Act (1919) ushered in perhaps the greatest marsupial slaughter in Tasmanian history. In the open season winters from 1923 to 1928 about 4.5 million ringtail possum, brush possum wallaby and pademelon skins were registered.[41] It is easy to imagine why at some stage the VDL Co increased its royalty on the Surrey Hills from one-sixth of all skins taken to one-third. It sent men with pack-horses around the leased runs every fortnight to collect skins. Harry Reginald Paine described a raid by police and VDL Co officers on a Waratah house owned by Joe Fagan which the company believed contained skins obtained without royalty payment from the Surrey Hills block.[42] However, the late 1920s and early 1930s were dark days economically, with only the 1931 gold price spike and government incentives like the Aid to Mining Act (1927) giving hope to rural workers. Many prospectors went looking for gold in the Great Depression years, and some got into trouble. In 1932 Luke Etchell and Cummings of Guildford sought and found the Waratah prospector WA Betts, after he was lost in the snow for two weeks. After giving him a good feed, they returned him to Guildford on horseback.[43] Again, Etchell was the man to whom people looked when someone went missing in the high country.

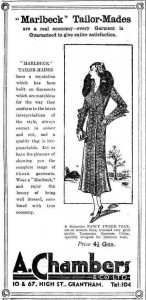

The fashionable British bride would not think of departing on her honeymoon without her Tasmanian brush possum collar coat in 1932. Advert from the Grantham Journal, 29 October 1932, p.4.

The open season of 1934, in which nearly a million-and-a-half ringtails were taken in Tasmania, was a godsend to the VDL Co which, during an unprofitable year for farming, made £500 out of hunting.[44] Thomas Etchell may not have been too wide of the mark when it predicted that an open season would benefit the community to the extent of £300,000–£400,000.[45] Did it benefit the possum population? The downside of that record-breaking season for hunters was that it was followed by two closed seasons while ringtail numbers recovered.

By the mid-1930s Luke Etchell was stockman for the shorthorn herds of RC Field’s Western Highlands Pty Ltd, which existed at least 1932‒38, and a regular correspondent with the police on hunting matters.[46] Ahead of the open season in 1937, for example, he advised Waratah’s Constable MY Donovan that ‘the Kangaroo and Wallaby were that numerous that they were eating the grass off and leaving the sheep and cattle on the runs short’.[47] Later that year, with the thylacine finally part protected and the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board keen to find living ones, Etchell was the ‘go to man’ for the Surrey Hills, Middlesex Plains, Vale of Belvoir and the upper Pieman. He suggested the hut in the Vale of Belvoir as a good base for the search.[48] He told Summers that ‘some years ago he has caught six or seven Native Tigers during a hunting season but for many years now he has not seen or caught any, proving that they have become extinct in this part, or driven further back’.[49]

Hut in the Vale of Belvoir. AW Lord photo from the Weekly Courier, 20 July 1922, p.22.

Benefiting from Etchell’s advice, and using Thompsons Park on the Surrey Hills block as another base, the government party, consisting of Sergeant MA Summers, Trooper Higgs, Roy Marthick from Circular Head and Dave Wilson, the VDL Co’s manager at Ridgley, scoured the region near Mount Tor, around the head waters of the Leven, the Vale of Belvoir and the Vale River down to its junction with the Fury and the Devils Ravine without finding signs of thylacine activity. A further search was conducted around the Pieman River goldfield and the coast north-west of there.[50] After commenting on the large numbers of brush possums in the area searched, Summers arranged for Etchell to secure seven pairs of black possums for the Healesville Sanctuary, Victoria.[51] Again, in 1941, Etchell advised that on the Surrey Hills, ‘the kangaroo and wallaby are plentiful … and that open season would be beneficial for everyone.[52]

There were bumper hunting seasons near the end of World War II and after it, with £15,000-worth of skins sold at the sale at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, more than 32,000 skins offered there in 1944 and record prices being paid at Guildford in 1946.[53] One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins for sale in 1943.[54] Taking advantage of high demand, in 1943 the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue—these included Painter Run (Painter Plain), Park Run (Old Park?), Mayday Run (Mayday Plain, now First of May Plain, in the furthest south-east corner of the Surrey Hills block), Talbots Run (presumably near Talbots Lagoon), Peak Run (Peak Plain), Black Marsh Run (probably near the site of the old Burghley Station), and those which probably corresponded to the mileposts on the Emu Bay Railway, the 25 Mile, 36 Mile and 46 Mile Runs. Like the traditional Cornish ‘tribute’ mining system, by which parties of men competed to work particular sections of a mine, the highest bid won the contract for each run. Men paying as much as £70 for seasonal rental of a run felt short-changed when heavy snowfalls curtailed their activities, which were still subject to the official hunting season. Nearly all the men who hunted the Surrey Hills block in 1943 combined this work with pulp wood cutting for Australian Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) at Burnie, or another job in the timber industry. Waratah’s Trooper Billing estimated that pulp wood cutting averaged seven hours per day, compared to 16 hours per day for snaring.[55] Billing regarded the Surrey Hills block as a game-breeding ground which damaged the interests of adjacent landholders.[56]

Luke Etchell posing before the Guildford skin sale in 1946. Winter photo from the Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

These bumper seasons were the end of the road for the Etchell brothers. Thomas Etchell died in September 1944.[57] Brother Luke was still snaring at 78 years of age in 1946, when the Burnie photographer Winter posed him in best suit, that apparently being the outfit of choice for hauling your skins on your shoulder to the Guildford sale.[58] Luke Etchell died in Hobart on 8 June 1948.[59] There were a few good hunting season after that, but in 1953 new regulations curbed an industry already reduced by weakening European and North American demand for skins. The era of the hunter-stockman and the professional bushman—the man who could live by his nous in the bush—was drawing to a close.

[1] ‘Van Diemen’s Land Company’, Hobart Town Courier, 25 September 1835, p.4.

[2] Edward Curr to Joseph Fossey, Woolnorth manager, 12 May 1830, VDL23/3 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [henceforth TAHO]).

[3] Edward Curr to James Reeves, Woolnorth manager, 2 April 1831, VDL23/4 (TAHO).

[4] Court of Directors to JH Hutchinson, Inward Despatch no.98, 10 October 1833, VDL193/3 (TAHO).

[5] See Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 8 February 1836, 30 June 1836, 10 August 1836, 14 September 1836 and 1 February 1837, VDL23/7 (TAHO).

[6] Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 6 March 1835, VDL23/6 (TAHO).

[7] For an overview of James Lucas’ work for the VDL Co, see Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000.

[8] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[9] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[10] VDL232/1/5, p.215 (TAHO).

[11] VDL232/1/5, p.255 (TAHO).

[12] VDL232/1/5, p.272 (TAHO).

[13] HW Wheelwright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[14] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

[15] James Wilson to James Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Notices to correspondents’, Launceston Examiner, 26 November 1879, p. 2; ‘Kangaroo hunting’, Cornwall Chronicle, 31 January 1879, p. 2.

[17] John Etchell was tried at the Derby Assizes 15 May 1843 for housebreaking, stealing money and assault, see CON33/1/53. http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-53,308,90,F,60 accessed 18 December 2016.

[18] Matthias Gaunt, ‘Indulgence’, Launceston Examiner, 1 December 1849, p.4.

[19] Birth registration 702/1869, Horton.

[20] Luke’s mother, Mary Ann Etchell, died at Waratah in 1903 (‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 October 1903, p.2).

[21] See file (SC195-1-57-7410, p.1) at https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=john&qu=etchell# accessed 18 December 2016.

[22] ‘Mining intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 28 September 1878, p.2. See also Charles Sprent’s dismissal of John Etchell’s alleged tin discovery at Brickmakers Bay in 1873 (Charles Sprent to James Norton Smith, 6 July 1873, VDL22/1/4 [TAHO]).

[23] ‘Stanley’, Mercury, 12 August 1880, p.3.

[24] ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.

[25] See Nic Haygarth, ‘William Aylett: career bushman’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.28–55.

[26] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 26 February 1880, p.4.

[27] Luke and Flora Etchell were convicted of stealing potatoes at Black River in 1883 (‘Emu Bay’, Reports of Crime, 20 April 1883, p.61; ‘Miscellaneous information’, Reports of Crime, 4 May 1883, p.70). Luke’s sister Sarah Ann was convicted of concealing the birth of a still-born child in pathetic circumstances in Waratah (‘Supreme Court’, Daily Telegraph, 22 August 1884, p.3). The most serious matter was his brother Thomas Etchell’s conviction of indecent assault in Waratah (‘Supreme Court, Launceston’, Mercury, 19 February 1896, p.3).

[28] ‘The Corinna fatality’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 November 1900, p.4.

[29] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 July 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 November 1900, p.2; ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 August 1905, p.2. In December 1900 Williams exhibited the skin of a tiger said to be seven feet long in Burnie (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 December 1900, p.2). For another Williams tiger story, see ‘Inland wires’, Examiner, 14 December 1900, p.7.

[31] Potential Williams bounties: no.344, 17 November 1899 (’10 October’); no.1078, 11 September 1902 (’31 July 1902’); no.1280, 2 December 1902; no.76, 20 February 1903 (’14 February 1903’), (’17 March 1902’). Etchell bounty: 25 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[32] J North, ‘A Waratah man’s opinion’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[33] ‘Local government: Waratah’, Daily Telegraph, 9 March 1910, p.7.

[34] ‘Tanner’s licences’, Police Gazette, 9 August 1912, p.183.

[35] For snaring see, for example, Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 16 July 1911, VDL22/1/47 (TAHO). For buying see for example, ‘Alleged illegal buying of skins’, Advocate, 27 July 1939, p.2.

[36] For the police raid, see Sergeant Butler to Superintendent Grant, 10 May 1937, AA612/1/12 (TAHO). See also ‘Trappers defrauded’, Mercury, 3 September 1930, p.9; and ‘Conspiracy charge’, Mercury, 4 September 1930, p.10. In 1943 police interviewed Harold Reuben Etchell in Wynyard but failed to find any illegally obtained skins (Detective Sergeant Gibbons to Superintendent Hill, 14 September 1943, AA612/1/12 [TAHO]).

[37] ‘Sheffield’, Advocate, 21 September 1937, p.6.

[38] See HS Allen to AK McGaw, 25 October 1907, VDL22/1/39 (TAHO). Thomas Etchell went osmiridium mining in 1919 during the peak period on the western field (see Pollard to the Attorney-General’s Department, 19 November 1919, p.113, HB Selby & Co file 64–2–20 [Noel Butlin Archive, Canberra]).

[39] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 20 February 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[40] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 27 June 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[41] Police Department, Report for 1925–26 to 1927–28, Parliamentary paper 41/1928, Appendix J, p.13.