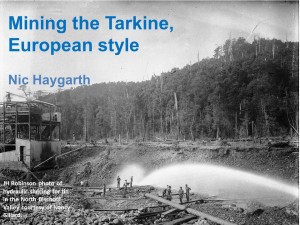

by Nic Haygarth | 27/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

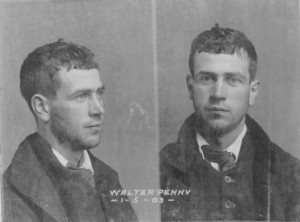

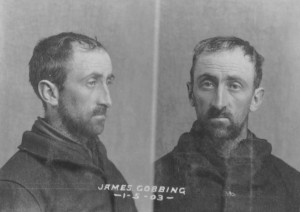

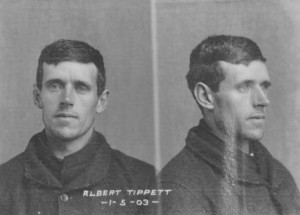

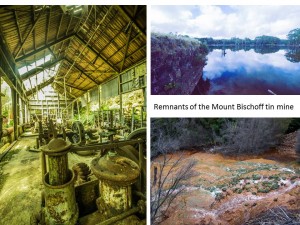

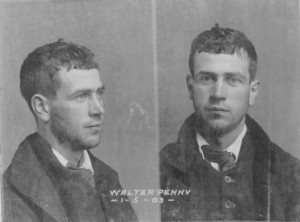

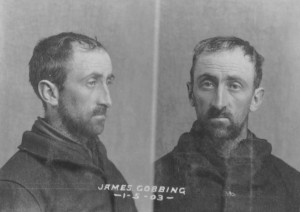

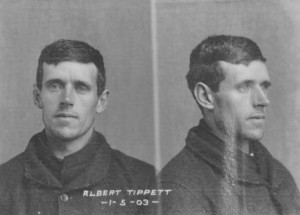

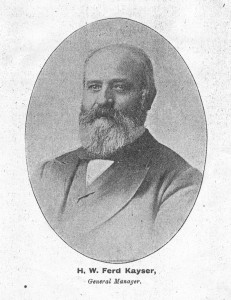

In 1903 three Waratah men—Walter Penney, James Cobbing and Albert Tippett—were gaoled for five years for receiving tin stolen from the Mount Bischoff Company. Yet the court case looked more like a showdown than a trial—the culmination of a 25-year feud between Ferd Kayser and his Cornish detractors. The three accused men worked the Waratah Alluvial plant on the Waratah River, which recovered tin lost into the water by the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds. They claimed that the tin they were accused of stealing had simply been retrieved from the bottom of the Waratah Alluvial dam on the river. The prosecution case was that the tin had been stolen directly from the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds earlier when Penney, Cobbing and Tippett worked there. At the dock, Kayser, the Mount Bischoff Co’s high profile general manager slugged it out with the canny Cornish tin dresser Richard Mitchell. Their on-going argument was ostensibly about the better ore processing method—German or Cornish. Yet in truth it was more about ego, reputation and the struggle to make a living.

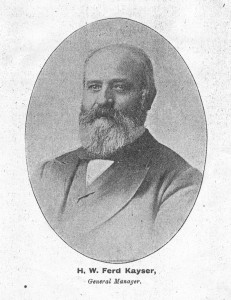

Mount Bischoff mine manager Ferd Kayser. Photo from the Australian Mining Standard, 1898.

The defence case rested on being able to show that the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds and its own tin recovery plants on the Waratah River were ineffectual, and that Mount Bischoff Co staff who had identified the stolen tin as being theirs were incapable of doing so. In speaking for the defence, Mitchell attacked Kayser’s ‘antiquated’ dressing machinery, claiming that his own plant (he was manager of the Anchor tin mine in the north-east) was ’50 years ahead of it’.[1] Laughably, Kayser failed to even identify Mount Bischoff Co dressed tin when it was placed in his hand at the dock. For five years he had been living away from the mine in Launceston as general manager, allowing John Millen to run the mine. Perhaps he was so out of touch that he had forgotten the appearance of the dressed tin he had produced for 23 years.

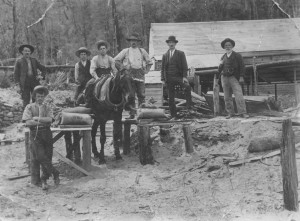

A succession of Cornish miners had been nipping at his heels throughout that time. Cornish miners asserted their superiority as hard-rock miners, exploiting their Cornish ethnicity as an economic strategy.[2] Being Cornish was their ‘brand’. Cornish miners were famous for their instinctive, canny style of management. They grew up mining from childhood, learning their craft on the job, without a formal mining education.[3] At Mount Bischoff Cornishmen they had tried to enhance this reputation by operating small retrieval plants, ‘lifting the crumbs from the rich man’s table’, that is, they had realised that the richest material on their leases was not lode tin or alluvial tin but escaped Mount Bischoff Co ore. The first to recognise this was the Waratah Tin Mining Company (Waratah Tin Co). Tailings from the Mount Bischoff Co sluice boxes emptied into a creek which ran through the Waratah Tin Co property into the Waratah River. In about 1878 that company’s Cornish tin dresser, Richard Mitchell, switched from working its tin lode to extracting ore from the creek.[4] Other Cornish tin dressers—ASR Osborne, William White and Anthony Roberts—followed suit. Their plants, the East Bischoff Company, Bischoff Tin Streaming Company, Bischoff Alluvial Tin Mining Company/Phoenix Alluvial Company and Waratah Alluvial Company, bore nicknames that suggested they were ‘shearing’ the Waratah River—the ‘Catch ‘em by the Wool’, ‘Shear ‘em’, ‘Shave ‘em’, ‘Hold ‘em’ and the ‘Catch ‘em by the Wool no. 2’ respectively.

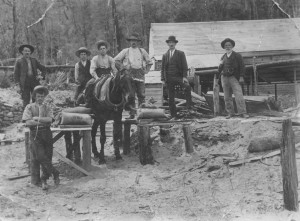

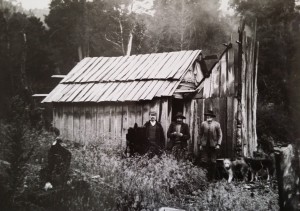

Cornish tin miner Anthony Roberts (right) operating a later tin mine, Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, in the North Bischoff Valley. Photo courtesy of Colin Roberts.

To many, Cornwall was a byword for simplicity, economy and improvisation. However, to Kayser, a champion of technology, Cornwall, the so-called ‘cradle of the Industrial Revolution’, was a ‘Luddite’. Antiquated Cornish mining methods were his favourite hobbyhorse. One of his first actions on taking over the management in 1875 was to sack the Mount Bischoff Co’s Cornish ore dresser Stephen Eddy, whose improvised appliances, he said, included ‘the hand-jigger and all the old primitive appliances his great grandfather used’.[5]

The Ringtail Sheds, in the period 1907-09, with the new power station below them at left. Stephen Hooker photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

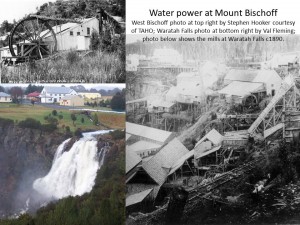

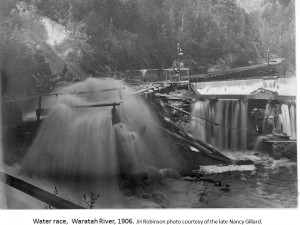

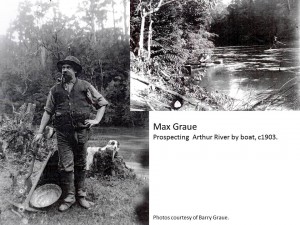

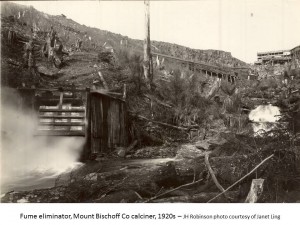

However, Kayser could not deny that there was plenty of ore for the Cornish tin dressers to retrieve. It has been estimated that the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds alone lost 22,000 tons of metallic tin into the Arthur River system up to 1907—30,000 tons by 1928. To put that in perspective, the Mount Bischoff Co produced about 56,000 tons of metallic tin, meaning that about one-third of the tin ore mined at Mount Bischoff ended up not in smelted bars for shipment to London, but in the Arthur River system. After deriding his Cornish rivals for years, in 1883 Kayser established the first of two tin recovery plants of his own on the Waratah River. The Ringtail Sheds at the base of the Ringtail Falls on the Waratah River stood on the old Waratah Tin Co block, where Richard Mitchell had set up the very first tin recovery operation five years earlier. Well-graded access tracks to the Ringtail Sheds were constructed from both sides of the Waratah River, the track on the western side being used to pack the ore out from the sheds.[6] These formed a loop by meeting at a foot bridge across the river just above Ringtail Falls, the site of the sheds. They are still used today to visit the Mount Bischoff Co Power Station which was afterwards built below the sheds. However, so much tin remained in the Arthur River system that in the 1970s the idea was entertained of dredging not just the river but coastal deposits outside the river mouth.[7]

(The mugshots above are from GD63-1-3, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.)

[1] ‘Alleged theft of tin ore’, Daily Telegraph, 22 April 1903, p.8.

[2] Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, Cornwall Limited Editions, Fowey, Cornwall, 2004 (originally published 1996), p. 234; Ronald M James, ‘Defining the group: nineteenth-century Cornish on the North American mining frontier’, in Cornish studies: Two (ed. Philip Payton), University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 1994, cited by Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, p.234.

[3] Geoffrey Blainey, The rush that never ended: a history of Australian mining, Melbourne University Press, 1978 (first published 1963), p.244.

[4] HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, no. IV, 1892, pp.350–51.

[5] HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, p.346.

[6] ‘Alleged theft of tin ore’, Daily Telegraph, 21 April 1903, p .4.

[7] ‘Tin worth $45 million in Arthur River’, Advocate, 10 May 1973, p. 1.

by Nic Haygarth | 05/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

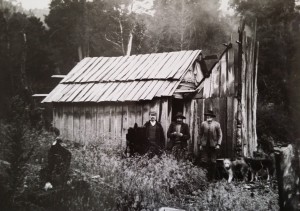

Stanniferous drift is a term once used to describe tin-bearing ground, but it could just as easily describe the movement of tin mining families—or mining families of any other stripe—from one field to the next in search of better opportunities. Both economics and personal tragedy prompted depopulation of the small Middlesex mining field in north-western Tasmania around the time of World War I (1914–18). The contemporary photographs of bushwalker and national park promoter Ron Smith help tell the tale.

Hut at the Iris tin mine, April 1905. (Left to right) Les Smith, Tom Murphy and Richard Kirkham. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Wooden sluicing pipes, Iris tin mine, 1990s.

Hut at the Iris tin mine, 1990s.

In Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, Simon Cubit and I told the story of the three Davis brothers, Clarence, Sidney (Sid) and Edmund (Eddie), who came to Tasmania from Victoria and tried to farm the Vale of Belvoir near Cradle Mountain in 1903.[1] When the farming venture failed, Clarence Davis returned home, but Boer War veteran Sid Davis (1879–1913) and Eddie Davis (1888–1944) stayed on in the Tasmanian highlands, taking up the lease of the Iris tin mine near Moina.

Charlie and Charlotte Adam with their three eldest children, Bell goldfield, 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

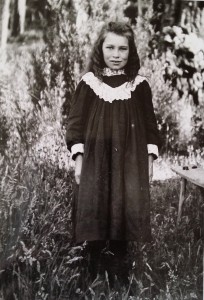

The Davis brothers’ partner in the mine was Charles Frederick Douglas Adam (c1864–1932).[2] Born in India as the son of an Anglo-Indian lieutenant, Adam had been sent home first to his parents’ house at Dover, England, to an aunt in France and to a Middlesex boarding school.[3] He is also said to have attended Eton, London and Cambridge Universities and the Sandhurst Academy—a busy schedule indeed, if it can be believed—before serving in the 81st Foot Regiment, with which he returned to India. Defective hearing prompted his retirement from the military, and he obeyed medical advice by settling in Australia. After a few years in Tasmania he arrived on the Bell Mount goldfield during the small rush there in 1892.[4] He made minor gold discoveries around the area at Golden Cliff and Stormont, and reworked the Bell goldfield when the hydraulic gold craze hit Tasmania. Charlie Adam married Charlotte Saltmarsh (1873–1946) in the nearby town of Sheffield in 1899.[5] They had children Charles William Guy Adam (1900), Mary Charlotte Adam (1902), Freda Kate Adam (1904), Frederick John Adam (1907), Robert Douglas Adam (1909) and Eileen.[6] There was also Charlotte’s daughter, Elsie (Elizabeth Mary Saltmarsh, born 1896), from a previous relationship.[7] Like many bush people, Charlie Adam used press subscriptions to keep up with the outside world, and his favourite was the weekly English illustrated newspaper The Graphic.[8]

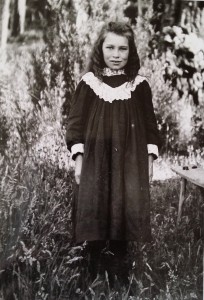

Elsie Adam, Bell goldfield, February 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

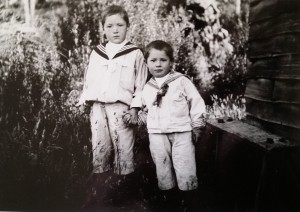

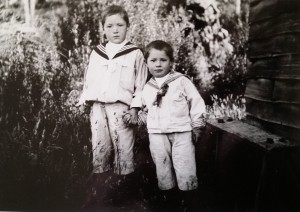

Guy and Mary Adam, Bell goldfield, February 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

However, at a time when there was no school at nearby Moina, the Adams’ most important education supplement was the tutor they employed, Mary Smith, to teach their three eldest children.[9] One of the things Mary taught was propriety. The manager of the biggest mine in the district was William Hitchcock but, offended by his surname, Mary pronounced it ‘Hitchco’. Did her silent ‘ck’ remove the problem or draw attention to it?[10]

Sid Davis came to dinner at the Adam house at the Bell goldfield, met Mary the tutor and began to court her. They married and established a farm at Black Jack, the long straight on what is now the Cradle Mountain Road south of Moina. From here Sid had a short walk to his other work at the Iris tin mine. The couple’s first child, Gladys, did not survive, but they had a second daughter, Hilda, in 1911, and another, Molly, two years later.[11]

Believed to be Sid and Mary Davis on their wedding day, 1909. Courtesy of Maree Davis.

Mary found the isolation difficult. Young Harold Tuson of Lorinna, on the eastern side of the Forth River, found out how lonely she was. In contrast to Charlie Adam’s highly regimented upbringing, this thirteen-year-old had just entered the workforce on a road gang, building the Cradle Mountain Road, and was camped near the Davis house. While returning home for the weekend he ran into Sid Davis on the road:

I suppose he wanted someone to talk to … ‘Where did you come from? And what do you do?’, and … he said, ‘Call in’. Little two-room place on the left … ‘Call in and have a talk to the wife. She’s very, very lonely’. And so on the Monday I did [call in]. And I’m carrying a songbook and she and I got to work and were singing … and I decided I’d better go and she wouldn’t allow me, she didn’t want me to go. ‘Sing another song …’[12]

In 1912 Gustav and Kate Weindorfer established Waldheim Chalet, their tourist resort at Cradle Valley. Charlie Adam was one of their first guests, but Weindorfer also availed himself of the Davises’ hospitality when caught on the road in bad weather. On more than one occasion he rocked young Hilda Davis to sleep in her cradle.[13]

On 14 May 1913 Sid went to work as usual at 7 am. Two-year-old Hilda accompanied her father to the gate. The family’s dog, Bob, followed at Sid’s heels until Mary called him home. She was busy in the kitchen four hours later when she heard a horse galloping up to the house, followed by a knock at the door. It was her friend, a lady named Ward, a frequent visitor. Imagining that she had bad news to impart, Mary immediately thought of her mother. ‘Don’t tell me’, she cried, ‘go and tell Sid!’ ‘I can’t’, her visitor replied, ‘he’s dead’.[14]

Sid Davis had been working in the open cut when a tree stump fell on top of him, striking him fatally on the back of the head. He had survived guerrilla warfare in South Africa only to succumb in a mining trench in peacetime. ‘It was such a blow to Mum, really and truly’, Hilda Davis recalled,

She never got over it … She was always thinking of her days at the mine and of Dad. She never got it out of her system. She loved those days up there …[15]

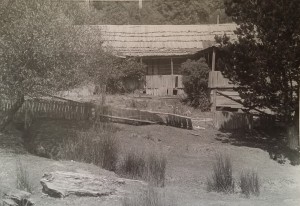

The abandoned Adam house at the Bell goldfield, February 1926. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

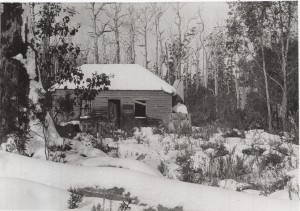

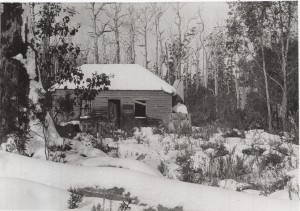

The deserted Davis house at Black Jack, Cradle Mountain road, August 1925. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Mary Davis tried to keep the Iris mine going, but having a four-month-old child at her breast made it impossible. Tin mining was scuppered by World War I soon after. There was an exodus from the small mining field. Mary Davis tutored children in Sheffield, but eventually returned home to her parents. Eddie Davis married Moina postmistress Lil Gurr, with whom he adjourned to Melbourne.[16] Elsie Adam married miner Watty Davis at her parents’ house but set up home at the tungsten and tin village of Storeys Creek.[17] Charlie and Charlotte Adam moved to Waratah, but eventually resettled in another mining region, the Latrobe Valley, Victoria. Three other Adam children settled in mining towns.[18] By the mid-1920s both the Adam and Davis houses, where so many children had grown and so many lives had intersected, were ruins. Of the characters of this story, only Gustav Weindorfer, the widowed proprietor of Waldheim Chalet, remained trying to eke a living from the mountains.

[1] Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.18–23.

[2] Australian Death Index, registration 13455/1932.

[3] British Census, 1881, Middlesex, Finchley, District 1, p.54. His birthplace was given as India; ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[4] ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[5] Married 10 May 1899, marriage registration 962/1899, Sheffield.

[6] Birth registrations 2326/1900, 2391/1902, 2518/1904 respectively. Frederick John Adam’s death certificate (7866/1972, Victoria) give his year of birth as 1907. Robert Douglas Adam’s World War II military record gives his date of birth as 29 January 1909, place of birth Moina. Eileen Adam is mentioned as a surviving child in Charlie Adam’s obituary, Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[7] Born 27 August 1896, birth registration 2328/1896, Sheffield.

[8] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[9] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991. Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995, remembered Mary Smith as being the tutor for William and Kate Hitchcock at Moina.

[10] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[11] Rose Ellen Gladys Davis was born 8 January 1910 and died 8 April 1910, birth registration 5417/1910, death registration 928/1910. Hilda May Davis was born 2 March 1911: Molly Davis was four months old at her father’s death: both facts from interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[12] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[13] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[14] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[15] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[16] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[17] See ‘Wedding bells’, Examiner, 12 April 1920, p.6.

[18] ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.