by Nic Haygarth | 23/05/25 | Story of the thylacine

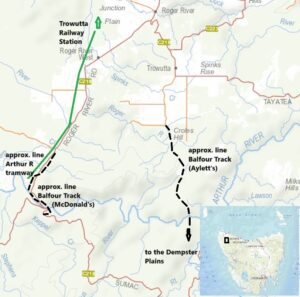

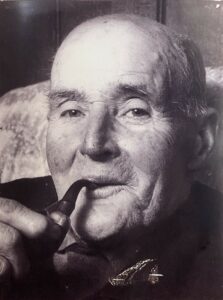

James ‘Tiger’ Harrison, Wynyard native animals dealer, snarer, prospector, track cutter, estate agent, shipping agent, Christian Brethren registrar, tourist chauffeur, human ‘cork’ and Crown bailiff of fossils. Photo from the Norman Larid files, NS1143, Tasmanian Archives (TA).

In the mid-1920s thylacines were still reported by bushmen in remote parts of the north-west. Luke Etchell claimed there was a time when he caught six or seven ‘native tigers’ per season at the Surrey Hills.[1] Like Brown brothers at Guildford, Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) hands at Woolnorth were still doing a trade in live native animals—although the latter property was out of tigers. On 7 July 1925 Hobart City Council paid the VDL Co £60 10 shillings for what can only be described as two loads of ‘animals’—presumably Tasmanian devils and quolls—recorded as being carted out to the nearest post office at Montagu during the previous month.[2] A further transaction of £30 was recorded in October 1925, when it is possible Woolnorth manager George Wainwright junior hand delivered a crate of live native animals to Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo.[3]

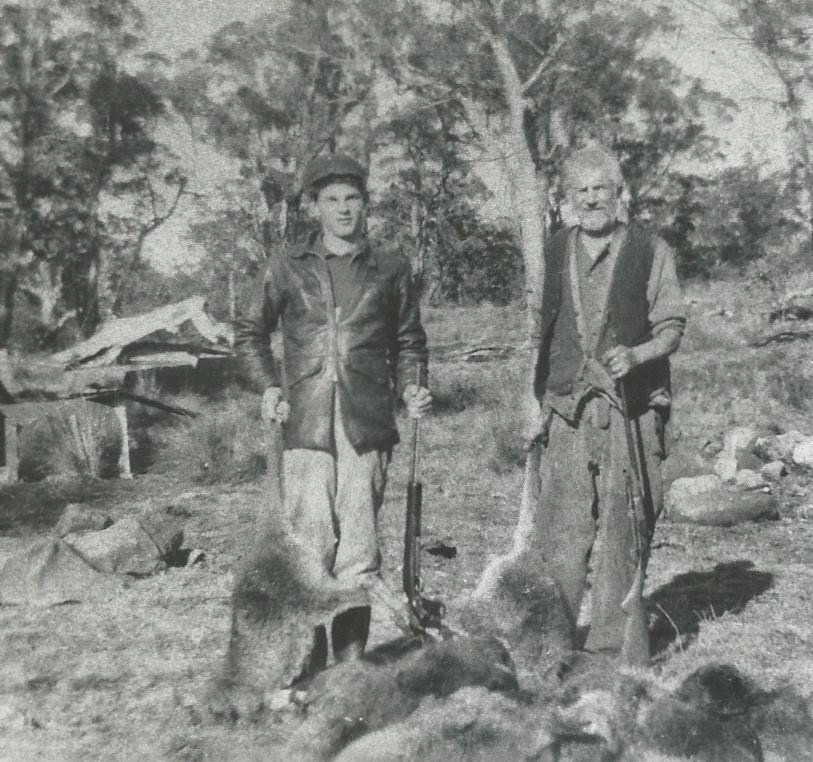

James ‘Tiger’ Harrison (1860–1943) of Wynyard took his animals dead or alive. He bought and sold living Tasmanian birds and marsupials, including tigers, but also hunted for furs in winter. In July 1926 Harrison and his Wynyard friend George Easton (1864–1951) secured government funding of £2 per week each to prospect south of the Arthur River for eight weeks.[4] However, their main game was hunting: the two-month season opened on 1 July 1926.

James Harrison’s collaborators George Easton and George Smith with a bark boat used to rescue Easton at the Arthur River in 1929. Photo courtesy of Libby Mercer.

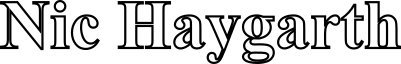

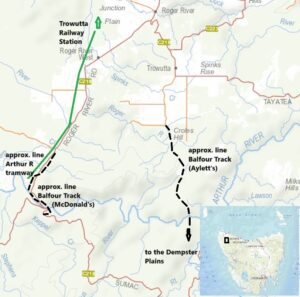

TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST©STATE OF TASMANIA

Easton, an experienced bushman in his own right, made snares most evenings until the pair departed Wynyard on 14 July.[5] At Trowutta Station they boarded the horse-drawn, wooden-railed tram to the Arthur River that jointly served Lee’s and McKay’s Sawmills.[6] Next day, Arthur Armstrong from Trowutta arrived with a pack-horse bearing their stores, and the pair set out along the northern bank of the Arthur towards the old government-built hut on Aylett’s track.[7] However, on a walk to the Dempster Plains to shoot some wallaby to feed their dogs, Harrison injured his knee so badly that he couldn’t carry a pack. So before they had even set some snares the pair was forced to return home.[8] On their slow, rain-soaked journey they sold their stores to the Arthur River Sawmill boarding-house keeper Hayes—the only problem being delivery of said stores from their position up river.[9] While Harrison went home by horse tram and car, Easton had to help Armstrong the packer retrieve the stores.[10]

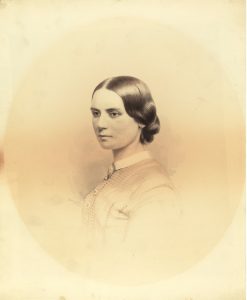

Martha Crole and her daughters. From the Weekly Courier, 10 April 1919, p.22.

The Crole house at Trowutta. From the Weekly Courier, 10 April 1919, p.22.

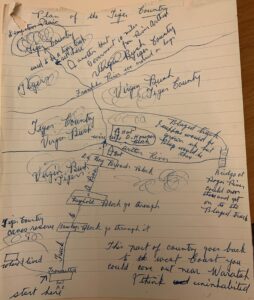

‘Tiger country’ around the Arthur River

If not for the injury Harrison may have secured more than furs over the Arthur. One of the European pioneers in that area was grazier Fred Dempster (1863–1946), who appears to have rediscovered pastures celebrated by John Helder Wedge in 1828.[11] Out on his run in 1915 Dempster met a breakfast gatecrasher with cold steel. The elderly tiger reportedly measured 7 feet from nose to tail and being something of a gourmet registered 224 lbs on Dempster’s bathroom scales.[12] In dramatising this shooting, anonymous newspaper correspondent ‘Agricola’ mixed familiar thylacine attributes with the fanciful idea of its ferocity:

This part is the home of the true Tasmanian tiger … This animal must not be confounded with the smaller cat-headed species [he perhaps means the ‘tiger cat’, that is, spotted-tailed quoll, Dasyurus maculatus] so prevalent beyond Waratah, Henrietta and other places. The true species is absolutely fearless in man’s presence, and if he smells meat will follow the wayfarer on the lonely bush tracks for miles, stopping when he does and going on when he resumes his walk. It has been proved beyond question that these brutes will not shift off the paths when met by man, and they will always attack when cornered.[13]

One mainland newspaper was apparently so confused by ‘Agricola’s’ account that he called Dempster’s thylacine ‘a huge tiger cat’.[14]

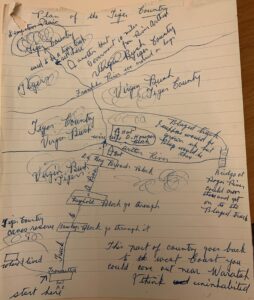

Trowutta people had no problem distinguishing quoll from tiger. They caught the latter unwittingly while snaring. Fred and Martha Crole and family of Trowutta made hundreds of snares on a sewing machine, eating the wallaby meat and selling the skins they caught. One of their boys, Arthur Crole (1895–1972), landed a tiger alive in a snare, killed it, tanned the hide and used it as a bedside rug.[15] While south of the Arthur, Harrison and Easton were unlucky not to run into Trowutta farmers Fred and Violet Purdy, who caught a tiger in a footer snare there during the 1926 season. When the Purdys approached the captured animal it broke the snare and disappeared. However, tigers also frequently visited their hut south of the river at night and they saw their footprints in the mud next morning.[16] Violet Purdy claimed to have spent six months straight living in the ‘wild bush’ (the hunting season in 1926 was only July and August), and her observations of the thylacine suggest someone with at least second-hand knowledge. Like ‘Agricola’, she knew of the tiger’s reputed habit of refusing to move off a track to let a human pass. Unlike him, she attested to the animal’s shyness. Purdy recommended ‘a couple of good cattle dogs’ as the means of tracking it down. She and her husband found thylacine tracks at the Frankland River as they crossed it to reach the Dempster Plains.[17] Decades later Purdy regaled the Animals’ and Birds’ Protection Board with her tales, illustrating them with a map of ‘tiger country’ between Trowutta and the Dempster Plains.

‘Tiger country’ between Trowutta and Dempster Plains, as it looked in 1926, according to Mrs V Kenevan,

formerly Violet Purdy of Trowutta. From AA612/1/59 (TA).

Snaring at Woolnorth

By the time Easton got home to Wynyard, Harrison, apparently recovered from his knee injury, had arranged for them both to snare at Woolnorth, where no swags needed to be carried, since stores were supplied. The VDL Co employed hunters every season to kill ‘game’, this serving the dual purpose of saving the grass for the stock and bringing the company income at a time of low agricultural prices. At this time hunters paid a royalty of one in six skins to the company.

Easton’s diary entries give rare insight into a hunting engagement. Harrison and Easton took the train to Smithton and caught the mail truck to Montagu, from which they were borne by chaise cart to the Woolnorth homestead. That night the snarers were put in a cottage generally reserved for the VDL Co agent, AK McGaw.[18] Next day station manager George Wainwright junior showed them their lodgings (tents next to a lagoon which served as the water supply) and how snaring (using springer snares but also neck snares along fences) and skinning were done at Woolnorth. Wainwright, an old hand, claimed to be able to skin 30 animals per hour.[19] Storms, horse leeches, which had a way of attaching themselves to the human scalp, and cutting springers and pegs kept the snarers very well occupied between snare inspections, an 11-km-long daily routine. The game was nearly all wallaby and ringtails, and Harrison and Easton dried their skins not in a skin shed but by hanging them in trees.[20] Bathing meant a sponge bath with a prospecting dish full of cold water—which also constituted the laundry facilities.[21] The last day of the season at Woolnorth was traditionally an all-in animal shoot, after which the season’s skins were baled, treated with an arsenic solution to kill insects and delivered to a skins dealer.[22] In the two-month 1926 season the VDL Co made £493 from the fur industry, a big reduction on the previous year (£1296) when the season had lasted three months.[23]

However, Harrison didn’t last the distance, calling it quits on 13 August after barely two weeks, leaving Easton to carry on alone until the season ended eighteen days later. Their skin tally at 13 August stood at 16½ dozen—198 skins or 99 apiece.[24]

Returning to ‘tiger country’

Once again ‘Tiger’ Harrison was in the wrong place at the wrong time to live up to his nickname. While he was working at tiger-free Woolnorth, timber worker, hunter and sometime miner Alf Forward snared two tigers, one alive, one choked to death by a stiff spring in a necker snare at the Salmon River Sawmill south of Smithton.[25] Forward is said to have exhibited the living one in Smithton before selling it to Harrison.[26] He almost had another live one in the following month, when a tiger detained by Forward’s snare for two days bit his capturer’s hand, thereby effecting its escape.[27]

Harrison eventually decided to cut out the middle-man. From 1927 he conducted expeditions specifically to obtain living thylacines to sell. He had no luck until in June 1929 he caught one 3 km south-west of Takone.[28] The Arthur River catchment remained ‘tiger country’ in the mid-1930s when ‘Pax’ (Michael Finnerty) and Roy Marthick claimed to have seen them while prospecting.[29] The question of whether they are there today still entertains Tarkine tourists and the worldwide thylacine mafia.

[1] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (Tasmanian Archives, henceforth TA).

[2 Payment recorded 7 July 1925. On 9 June 1925: ‘W Simpson taken animals to Montagu’; 22 June 1925: ‘W Simpson went to Montagu with load of animals’, Woolnorth farm diary, VDL277/1/53 (TA).

[3] Payment recorded on 13 October 1925. On 4 October 1925 George Wainwright junior and his wife departed Woolnorth for the Launceston Agricultural Show (Woolnorth farm diary VDL277/1/53). It is possible that he took a crate of animals on the train to Hobart.

[4] GW Easton diary, 1 July 1926 (held by Libby Mercer, Hobart).

[5] GW Easton diary, 1–14 July 1926.

[6] GW Easton diary, 15 July 1926.

[7] GW Easton diary, 16 July 1926.

[8] GW Easton diary, 18 July 1926.

[9] GW Easton diary, 23 July 1926.

[10] GW Easton diary, 25 and 26 July 1926.

[11] JH Wedge, ‘Official report of journeys made by JH Wedge, Esq, Assistant Surveyor, in the North-West Portion of Van Diemen’s Land, in the early part of the year 1828’, reprinted in Venturing westward: accounts of pioneering exploration in northern and western Tasmania by Messrs Gould, Gunn, Hellyer, Frodsham, Counsel and Sprent [and Wedge], Government Printer, Hobart, 1987, p.38.

[12] See for example ‘Boat Harbour’, North West Post, 22 February 1915, p.2. Dempster probably didn’t have any bathroom scales with him. Rather mysteriously, the author of ‘A huge tiger cat’, Westralian Worker, 19 March 1915, p.6, put the animal’s weight as ‘2 cwt’ (224 lbs).

[13] ‘Agricola’, ‘Farm jottings’, North West Post, 24 February 1915, p.4. In another column ‘Agricola’ claimed with equal dubiousness that under Mount Pearse trappers caught tigers in pits, and that if more than one tiger was collected in the same pit at the same time the captured animals would fight to the death. See ‘Agricola’, ‘Farm jottings’, North West Post, 10 July 1914, p.4.

[14] ‘A huge tiger cat’, Westralian Worker, 19 March 1915, p.6.

[15] Fred and Graham Crole, in Women’s stories: different stories—different lives—different experiences: a Circular Head oral history project (compiled and edited by Pat Brown and Helene Williamson), Forest, Tas, 2009, p.192.

[16] The hut was on Aylett’s Track to Balfour.

[17] Violet Kenevan, Kingswood, New South Wales, to secretary of the Animals’ and Birds’ Protection Board, 30 October 1956, AA612/1/59 (TA).

[18 GW Easton diary, 27 July 1926.

[19] GW Easton diary, 30 July 1926.

[20] GW Easton diary, 18 August 1926.

[21] GW Easton diary, 15 August 1926.

[22] GW Easton diary, 31 August and 6–9 September 1926; Woolnorth farm diary, 31 August 1926, VDL277/1/54 (TA).

[23] The figures are from VDL129/1/7 (TA).

[24] GW Easton diary, 13 August 1926.

[25] ‘Hyena choked in snare at Salmon River’, Circular Head Chronicle, 11 August 1926, p.5.

[26] ‘TT, from New Town’, ‘Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 24 August 1954, p.4, claimed that Alf Forward caught the animal in a kangaroo snare at the Salmon River ‘less than 30 years ago’ and sold it to Harrison after putting it on show in Smithton.

[27] ‘Hand bitten by a hyena’, Circular Head Chronicle, 29 September 1926, p.5.

[28 GW Easton diary, 17 June 1929; Circular Head Chronicle, 29 May 1929.

[29] See ‘Pax’ (Michael Finnerty), ‘A “bush-whacker’s” experience in the north-west’, Mercury, 6 May 1937, p.8; Roy Marthick to the Fauna Board, 10 February 1937 (TA); Roy Marthick quoted by Charles Barrett, ‘Out in the open: nature study for the schools’, Weekly Times (Melbourne), 10 July 1937, p.44.

by Nic Haygarth | 06/10/24 | Tasmanian high country history

The collection of farms known as Narrawa in north-western Tasmania produced some tough old buggers. The small community west of Wilmot was home to the Carters, Vernhams, Williamses, Bramichs, Lehmans and others, bush farmers resigned to grubbing out, burning and stump jacking their way to cleared pasture. Crops like potatoes were planted in the ashes of the burnt trees as the beginning of farming operations.

Jack (aka Johnny) Carter, Bill ‘Yorky’ Smith and Jack ‘Boy’ Griffiths clearing land at Narrawa. Griffiths, standing precariously on the log stack, was later killed in a similar operation on the Williams farm. Courtesy of Peter Carter.

After the harvest came the hunt. This was a chance to earn enough money to keep self and family for the rest of the year. Each hunter had his own territory somewhere in the north-western highlands.

Harry ‘Poke’ Vernham/Vernon/Varnham (c1885–c1954)[1]

By the age of 20 Narrawa farmer Charles Henry Vernham already knew his way around Cradle Mountain, being conscripted in the search for hunter Bert Hanson who had gone missing near there in a winter fog.

[2] Harry excited more legends than probably any other bushman in his neck of the woods. He was a small man who, paradoxically, wore sandshoes (sneakers) in the bush. Harry was ‘square as a brick’ but so tough ‘you could drive nails into him and you wouldn’t hurt him’.

[3] Two stories bear out his toughness. In the snaring season of 1906 Harry cut his knee with an axe in the snow at Henrietta south of Wynyard. He covered the wound with salt and bandaged it with a green wallaby skin, telling his hunting partner ‘You’ll have to do all the snaring. I’ll peg out the skins and do all the cooking’.

[4] Eventually Harry presented himself to a doctor, who told him that he was just in time to prevent the onset of gangrene.

[5] Harry was then admitted to the Devon Cottage Hospital at Latrobe.

[6] Hearing of her son’s accident, Harry’s mother walked about 30 km from Wilmot to Latrobe to prevent a surgeon amputating his leg. She succeeded, but Harry was left with a stiff leg for the rest of his life.

[7]

A young Harry Vernham sitting second from right in the second Bert Hanson search party, Weekly Courier, 30 September 1905, p.20.

On another occasion Harry’s nose was virtually detached from his face in a motorcycle accident.

[8] A doctor told him, ‘I’d better give you a whiff of something before I stitch it back on’. Harry is said to have replied, ‘I didn’t have a whiff when it come off so I don’t need one putting it back on’.

[9]

Hunting exploits

In 1914 Harry married Annie Eliza Carter, from the neighbouring family.

[10] They had a boy and three girls over the next four years, but Harry’s nickname Poke suggests that his sex life didn’t end there. At least the hunting seasons were celibate. Harry and his brother George Matthew ‘Native’ Vernham (1889–1966)

[11] had a hut on the south-eastern side of Mount Kate and a little log hut near the site of the present-day Cradle Mountain Lodge, the latter being pretty schmick as it was a lock-up affair.

[12] Other Harry Vernham hunting companions included Ernest ‘Son’ Bramich (1914) and Harry Leach (1933).

[13] Ted Murfet recalled camping with Harry in later years at Middlesex Station, the Twin Creeks Sawmill huts, the hut at Learys Corner, Daisy Dell and Robertson’s on the track into the Vale of Belvoir.

[14] They took a dozen balls of hemp for a season and used an old eggbeater to make up their treadle snares on a board about 1.2 m long. Usually they’d need 1000 snares for the season. In their worst season the pair shared £300 and in their best the take was £700—£350 each.

[15] By this time Harry had moved beyond the medicinal qualities of a green wallaby skin, developing new home remedies. He treated an ulcer on his leg with a plaster of onion wrapped up in a sock as a bandage and addressed a cold with swigs of Worcestershire sauce.

[16]

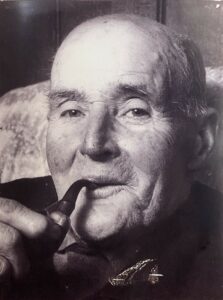

Harry Vernham (right) hunting much later in life. Courtesy of David Ball.

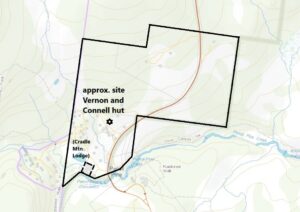

TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST© STATE OF TASMANIA

The slow farm development ritual undertaken at Narrawa also applied to the Connell family when they took up the Dunlavin property at the top of Chinamans Hill, Lower Wilmot, in the 1890s. While his older brother Lionel Connell (1884–1960) became a miner, Gordon stayed on the farm.

[18] He married Alice Jacklin in 1911, and the couple had at least four children during the next decade.

[19] In 1915/16 Lionel Connell and Dick Nichols built a hunting hut in the Little Valley, south of Lake Rodway, and in 1917, when Lionel took a 3-month sabbatical from the Shepherd and Murphy Mine to go hunting, his younger brother Gordon joined him at Cradle.

[20] Known as Bull because of his huge shoulders and great physical strength, Gordon hunted with Lionel as far south as the plains between Barn Bluff and the Fury River. He also worked over the so-called Todds Country at the head of the Campbell River.

[21] Gordon had a big kangaroo dog called Slocum which would take him to his kills. One day Gordon put his feet up and smoked for 30 minutes before Slocum returned. ‘Where is he then?’, the master prompted, setting the dog off towards Lake Carruthers to a big kangaroo he’d killed. But Slocum wasn’t finished, refusing to budge. ‘Well where is he then?’. Off they went again beyond Lake Carruthers to another big kangaroo carcass.

[22]

Gordon Connell, courtesy of Malcolm Dick.

Gordon hunted with Harry Vernham at Cradle in 1925 and 1926 and in other years around Middlesex and the Vale of Belvoir.

[23] They developed a regime of line camps or temporary shelters to get around their extensive snare lines, arriving at base camp only every three days. Gordon recalled icicles forming on Harry’s formidable body hair as he lugged his bag of skins about the snare lines. When Harry stripped off his shirt a huge cloud of steam arose from his singlet, an unusual form of enveloping fog. Wild bulls remaining from Field brothers’ Middlesex grazing operation were an occasional problem for hunters. The worst of these was a territorial bull called Bob because of the ‘bob’ in his tail. Another bull they put a bullet in roared back to life as they approached its apparent corpse. Gordon had a way of cutting a cartridge with a knife to concentrate its potency, but on this occasion it seems to have had the opposite effect.

[24]

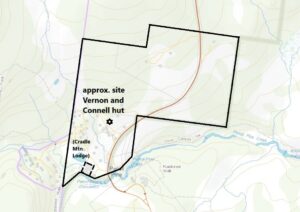

The Vernham and Connell 99-acre block at Pencil Pine Creek. TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST© STATE OF TASMANIA

How the area looked in 1949, showing the position of the hunting hut. Crop from aerial photo 0196_483, 15 April 1949.

In the 1930s Poke and Bull selected and started to pay off a 99-acre-block at Pencil Pine Creek enclosing the log hut and the old FH Haines sawmill site—land now partly occupied by Cradle Mountain Lodge, the Cradle Mountain shop and rangers’ quarters. Presumably they were either safeguarding their hold on valuable hunting territory or foresaw future tourism development. The pair failed to pay it off, and Lionel and Margaret Connell took over the payments. Lionel’s family were still using the log hut in 1940. Like most hunting huts in the area it had a skin shed chimney, that is, a very large timber chimney in which skins were pegged to dry close to the fire.

[25]

The tiger stories

Peter Carter, Harry Vernham’s nephew, claimed that Harry caught thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) in ‘hell-necker’ or ‘hellfire necker’ snares positioned at each end of a hollow log that contained a live wallaby. The ‘hellfire’ appears to have been a heavy-duty neck snare—not terribly surprising, as plenty of tigers were strangled in neck snares. What is surprising is Peter’s claim that his uncle sold skun tigers, that is, tiger carcasses, for £5. Perhaps he meant that he sold tiger skins for £5.

[26] Harry Vernham’s name was never entered on the list of payees for the £1 per head government thylacine bounty, although it is possible he claimed bounties through an intermediary. Still, the question needs to be asked why he went to so much trouble to strangle a tiger in a neck snare, when he could just have easily snared it alive by the paw in a foot or treadle device which would have earned him much more money. The story would only make sense if Harry had learned the whereabouts of a tiger or family of tigers and set up the hollow log trap as above, making sure the wallaby was restrained so that it couldn’t spring the snares while making its escape. Prices paid for tigers, dead or alive, varied wildly, so it’s hard to put even an approximate year on Vernham’s tiger sales.

[27]

Gordon Connell is another name missing from the government tiger bounty register. He once caught a thylacine dead in the snare—presumably a necker snare which strangled it—but he encountered others in the wild. Bull was said to have found a thylacine lair in one of three rock shelters down in the Fury Gorge while hunting nearby. He shouldn’t have been surprised then when, hunting the button-grass plains above it out of season, he heard an animal yelp. A big kangaroo hopped up the slope, as if disturbed, convincing Gordon and his mate that the police were below them. Then a tiger came up the slope in pursuit of the kangaroo. At regular intervals it stopped and gave three sharp yelps before continuing the chase, as did a second tiger behind it.

[28]

What a pity neither Poke nor Bull put pen to paper! We know so little about hunters’ experiences with tigers, but at least these anecdotes give glimpses of what they passed down through family and the hunting community.

[1] Years of birth and death are from Ancestry.com.au, no birth certificate or will was found.

[2] ‘Lost in the snow: a second search party’,

North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 July 1905, p.3.

[3] Peter Carter, interviewed by David Bannear, 16 July 1990, in

What’s the land for?: people’s experiences of Tasmania’s Central Plateau region, Central Plateau Oral History Project, Hobart, 1991, vol.3, p.4.

[4] Warren Connell, interviewed 8 September 1997; David Ball, interviewed 25 April 2020.

[5] Warren Connell.

[6] ‘Latrobe’,

North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 29 August 1906, p.2.

[7] Len Fisher,

Wilmot: those were the days, pp.46–47

[8] ‘Ulverstone’,

Advocate, 26 March 1934, p.6.

[9] David Ball, 24 April 2020. Ted Murfet also told this story to Len Fisher in

Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Devonport, 1990, p.82.

[10] Married 15 October 1914, marriage record no.801/1914, registered at Wilmot (TA).

[11] Born to Blackwood Hill, West Tamar labourer William Varnam [sic] and Christina Bowers on 1 February 1889, birth record no.736/1889, registered at Beaconsfield, RGD33/1/68 (TA),

https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=varnham, accessed 3 October 2023; died 7 February 1966, Will no.47656, AD960/1/105 (TA),

https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=vernham, accessed 3 October 2023.

[12] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 12 July 1914 (Pencil Pine Creek), 23 July 1914 (east side Mount Kate), NS234/27/1/4 (TA); 10 July and 10 August 1925 (Pencil Pine Creek) (QVMAG). Es Connell, interviewed by Nic Haygarth on 23 September 1997, confirmed the location of this hut.

[13] Gustav Weindorfer, in his diary, 16 and 18 June 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TA), recorded Harry Vernham and Bramich hunting Cradle Valley and Hounslow Heath with dogs. For Leach see ‘Taking game in close season alleged’,

Advocate, 12 September 1933, p.2.

[14] Ted Murfet, interviewed 15 October 1995.

[15] Ted Murfet, interviewed 15 October 1995.

[16] Ted Murfet, in Len Fisher,

Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Devonport, 1990, p.81.

[17] Born 29 April 1889 to Michael Connell and Frances Sayer, birth registration no.2639/1889, registered at Port Frederick, RGD33/1/68 (TA),

https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=gordon&qu=murray&qu=connell#, accessed 18 August 2024. The family was living at Torquay (East Devonport).

[18] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.10;

Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office Directory, 1919, p.277.

[19] Married 28 March 1911, file no.1384/1911, registered at Gunns Plains (TA).

[20] Gustav Weindorfer diary 29 December 1915 (Lionel Connell and Dick Nichols arrive at Cradle from Moina), NS234/27/1/5 (TA); 1–26 April 1917, NS234/27/1/7 (TA). Weindorfer possibly also referred to Gordon Connell in diary entries in May and June 1917, NS234/27/1/7 (TA).

[21] Todds Country was a name given by snarers to territory hunted by Bill Todd (1855–1926).

[22] Warren Connell.

[23] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 14 July 1925 and 23 March 1926 (QVMAG).

[24] Warren Connell.

[25] RE Smith diary, 29 June 1940, NS234/16/1/40 (TA).

[26] Peter Carter, p.10.

[27] For example,in James 1928 Harrison sold a tiger carcass to Colin MacKenzie in Melbourne for £12 (Harrison’s notebook). In 1930 Wilf Batty sold the carcass of the tiger he killed at Mawbanna for £5 (Wilf Batty; quoted in ‘The $55,000 search to find a Tasmanian tiger’,

Australian Women’s Weekly, 24 September 1980, p.41).

[28] Warren Connell.

by Nic Haygarth | 10/08/24 | Story of the thylacine

At Pisa Cemetery the Parkers, O’Connors, Gatenbys and Smiths are all equals. Some of course are more equal than others, having large, decorated headstones and obelisks, but their bones moulder in the same clay and their spirits, should they have any, mingle on the same windswept plain rolling back to the blue profile of the Great Western Tiers. It is remarkable that the graves of John (c1822–1903) and Hannah Jane Smith (c1819–1903) are marked at all. It doesn’t get more anonymous than being John Smith, and the anonymity of a bare patch between the plinths of their betters awaited most of the likes of these two. Perhaps their old employer Roderic O’Connor (1849–1908) gave them a monument as a mark of respect.

Pisa (St Mark’s Anglican, Lake River) Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

The irony of that action wouldn’t have been lost on John Smith, one of 314 bearers of that name conscripted to Van Diemen’s Land. A native of Nottingham, Jack was a single, semi-literate, 170-cm-tall labourer when sentenced to 7 years’ transportation for stealing a pair of shoes and a hatchet as a 20-year-old in 1842. The hatchet was a token of a combative life. He had a prior conviction and five short prison terms under his belt, being, apparently, ‘a bad irreclaimable lad, connected to other lads who live by plunder’. Transported on the Forfarshire, he appears to have laboured in a probation gang at Westbury before his attempts to abscond landed him in the Port Arthur Gaol. Jack spent 3½ years in the probation system, enduring 179 lashes, 88 days of solitary confinement and 21 months of hard labour in chains before being released for private service in 1847 at the age of about 25. What would his opinion have been at that time about whether transportation was a sentence or an opportunity?

The monument marking the graves of John and Hannah Jane Smith, Pisa Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photos.

Jack then worked for Edward Archer of Northbury, Longford (nearly two years), and Joseph Oakley of Oatlands, achieving freedom by servitude at the expiry of his sentence in 1849.[1]

Perhaps he still brandished that hatchet, because within a few years Jack was living by plunder once more, working out of a hide-out near Millers Bluff. Known as ‘Jack the Hunter’, in the mould of the Irish outlaw ‘Jack the Shepherd’, he was accused of rustling sheep from the large properties adjoining the slopes of the Great Western Tiers. In 1856 graziers Arthur O’Connor of Connorville and Charles Parker of Parknook tracked him down and sent a volley his way. Jack raised his weapon at O’Connor but it failed to discharge, and he made his escape.[2] The threat Jack posed to wool-growing was raised in parliament.[3] An armed police party sent to apprehend him mistakenly pounced on a roving entomologist at the Hummocky Hills.[4] A posse led by District Constable Thomas Kidd of George Town did better, finally arresting Jack the Hunter or ‘Hellfire Jack’[5] at Hells Bottom on the slopes of Millers Bluff in 1858. Here they also found the evidence of his ovine crimes in a veritable maze of hideouts, including an underground wool store. Jack was shot in the arm while trying to escape, newspaper reports varying in their accounts of his injuries.[6] His victims, the Gatenbys and O’Connors, secured two of his hunting dogs as a form of recompense.[7] The ex-convict was sentenced to four years’ gaol for stealing 15 sheep worth £8 from George Gatenby of Barton.[8]

In 1870 a newspaper writer recounting Jack’s tale commented that ‘Poor Jack, now in confinement, must look back with harrowing regret to his wild hut high on the tier’.[9] In fact Jack was already back on the tier.[10] Somehow Arthur O’Connor had forgiven his depredations and allowed him back onto Connorville—presumably as a shepherd! After all, there’s no substitute for local knowledge. Jack’s residence was Boomers Bottom, a sheep run where the Lake River cut a passage down through the mountains. Adam Jackson’s 1847 survey of the upper Lake River didn’t recognise Hells Bottom but mapped Scrubby Den and the even more tantalising Tigers Bottom.

Adam Jackson’s 1847 survey of the upper Lake River where there be tigers. Copyright State of Tasmania.

Jack was certainly at Connorville in 1885 when ‘Jimmy the Sailor’ Casey saved his five-year-old from drowning in the mill race.[11] But Jack was more than a father and a hunter: he was a serial thylacine decapitator. He buried his hatchet in tigers’ necks. The submission of severed animal heads to unsuspecting public officials sounds like something out of The Godfather.[12] However, this seems to have been acceptable behaviour at the time. At least twelve thylacine heads were presented to the Longford warden or police office for payment in the years 1888–97, Connorville and Parknook being star killing fields.[13] Jack produced eight of these, probably securing them in necker snares.[14] In 1897 he claimed to have killed about 130 tigers during 30 years’ residence at Boomers Bottom.[15] It is possible that Jack managed a line of necker snares across a gully through which tigers were thought to be entering the Connorville property, in the fashion of the Woolnorth ‘tigerman’ at Green Point in the far north-west. Even so, four tigers per year hardly constitutes an invasion, and we do not know if any of those 130 savaged any of Connorville’s 14,000-strong grazing flock.[16]

Jack’s partner Hannah Jane Smith predeceased him by nine months.[17] Her story, like those of so many other anonymous wives and female partners, is unknown. Their child or children are also untraceable, their births seemingly evading the registrar. Perhaps Hannah helped Jack secure his sixteen £1 government tiger bounties.[18] That would have paid for some sugar, tea, tobacco and snaring hemp or wire but not saved them from kangaroo leather ensembles and a diet of macropod and potato. Perhaps Jack’s hunting was a lot more lucrative than that in the backblocks of Connorville. Perhaps Jack and Hannah lived at a distance in mutual contempt. We will never know. They keep their secrets beneath the loam at St Mark’s, Lake River, where the tigers once roamed.

[1] Conduct record for John Smith per Forfarshire, CON33/1/44, p.197 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA), https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON33-1-44/CON33-1-44p197; Conduct record for John Smith per Forfarshire, CON37/1/9, image 216 (TA), https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON37-1-9, both accessed 4 August 2024.

[2] ‘Bushranging’, Launceston Examiner, 18 September 1856, p.3.

[3] ‘House of Assembly—last night’, Courier, 9 October 1858, p.2.

[4] ‘An Old Vet’, ‘Jack the Hunter: an episode in a VDL policeman’s life’, Daily Telegraph, 4 January 1895, p.6.

[5] ‘Capture of another bushranger’, Courier, 8 October 1858, p.3. ‘Hellfire Jack’ was also the nickname of the ex-convict John Snelson.

[6] ‘Bushranging in Tasmania’, Courier, 8 October 1858, p.3.

[7] George Gatenby diary, 31 August and 1 September 1858, NS1255/1/1 (TA).

[8] ‘Oatlands Supreme Court’, Hobart Town Advertiser, 3 January 1859, p.7.

[9] ‘Aegles’, ‘Notes in north Tasmania’, Launceston Examiner, 15 February 1870, p.5 (reprinted from the Leader [Melbourne]).

[10] ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[11] ‘Cressy’, Mercury, 22 September 1885, p.4.

[12] The Godfather, a 1972 movie directed by Francis Ford Coppola, included a scene in which a severed horse’s head was placed in the bed of a sleeping man.

[13] Longford notes’, Launceston Examiner, 2 August 1888, p.5; ‘Longford notes’, Launceeston Examiner, 2 July 1889, p.4; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 13 March 1890, p.3; ‘Longford’, Mercury, 4 October 1890, p.2; ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 30 September 1891, p.2; ‘Country intelligence’, Tasmanian, 27 August 1892, p.30; ‘Longford’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1893, p.2; ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[14] ‘Longford’, Launceston Examiner, 13 March 1890, p.3; ‘Longford notes’, Tasmanian, 4 October 1890, p.22; ‘Country intelligence’, Tasmanian, 27 August 1892, p.30; ‘Longford’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1893, p.22;

[15] ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[16] The size of the sheep flock is from E Richall Richardson, ‘A tour through Tasmania (letter no.73): Connorville’, Tribune, 12 November 1877, p.2.

[17] Headstone, Pisa Cemetery.

[18] Bounties no.582, 17 December 1889; no.81, 18 March 1890; no.354, 20 August 1890; no.463, 7 October 1890; no.62, 26 March 1891; no.184, 22 May 1891; no.822, 1 April 1892; no.272, 12 September 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.123, 19 June 1893 (2 adults); no.13, 5 March 1895; no.37, 30 [sic] February 1896; no.39, 5 March 1897 (3 adults); no.45, 17 March 1898 (‘2 March’), LSD247/1/2 (TA).

by Nic Haygarth | 26/09/21 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

Stephen Spurling III (1876–1962) rode the rails and marched the mountains in his quest to snap Tasmania. Revelling in ‘bad’ weather and ‘mysterious’ light, this master photographer shot the island’s heights in Romantic splendour. His long exposures of the lower Gordon River are likely to have helped shape the reservation of its banks in 1908.[1] Snow-shoed, ear-flapped and roped to a tree, he captured Devils Gullet in winter and froze the waters of Parsons Falls. But Spurling wanted to record the full gamut of life. He was there when the whales beached, the bullock teams heaved, the apple packers boxed antipodean gold and floodwaters smashed the Duck Reach Power Station. His lens was ever ready.

Stephen Spurling III in 1913, photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Oddly, just about the only thing Spurling didn’t snap was a sack full of thylacine heads which he claimed to have seen at the Stanley Police Station in 1902. Forty-one years after the event, Spurling wrote that he watched ‘cattlemen from a station almost on the W coast [produce] two sacks of tigers’ heads (about 20 in number) and [receive] their reward’.[2] One-hundred-and-nineteen years after the event, this claim is hard to reconcile with the records of the government thylacine bounty. It adds a puzzle to the story of the so-called Woolnorth tigermen.

The Woolnorth tigermen

About 170 thylacines were killed at the Van Diemen’s Land (VDL Co) property of Woolnorth in the years 1871–1912, mostly by the company’s tigermen—a lurid title given to the Mount Cameron West stockmen. The tigermen had a standard job description for stockmen, receiving a low wage for looking after the stock, repairing fences, burning off the runs and helping to muster the sheep and cattle. They supplemented their income by hunting kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons, ringtail and brush possums. The only departure from the normal shepherd’s duty statement was keeping a line of snares across a neck of land at Green Point—now farming land at Marrawah—where the supposedly sheep-killing thylacines were thought to enter Woolnorth. The VDL Co paid their employees a bounty of 10 shillings for a dead thylacine, which was changed to match the government thylacine bounty of £1 for an adult and 10 shillings for a juvenile introduced in 1888. To make a government bounty application the tiger killer needed to present the skin at a police station, although sometimes thylacine heads sufficed for the whole skin.

It is not easy to work out how or even whether the Woolnorth tigermen generally collected the government thylacine bounty in addition to the VDL Co bounty. It is reasonable to think that the VDL Co would have encouraged its workers to do this, since doubling the payment doubled the incentive to kill the animal on Woolnorth. However, only two men are recorded as receiving a government thylacine bounty while acting as tigerman, Arthur Nicholls (6 adults, in 1889) and Ernest Warde (1 adult, 1 juvenile, in 1904).[3] This suggests that if Woolnorth tigermen and other staff received government thylacine bounties they did so through an intermediary who fronted up at the police station on their behalf.

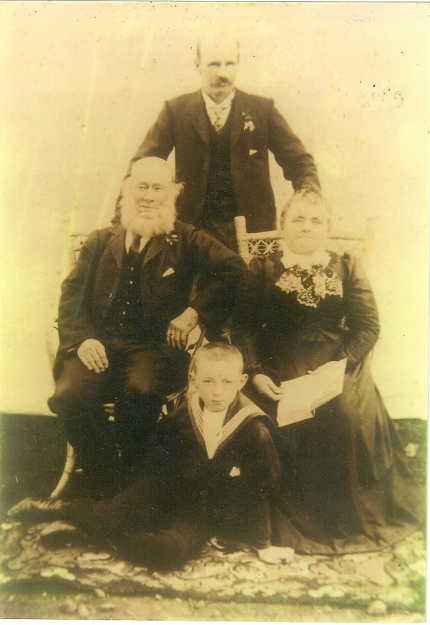

Charles Tasman Ford and family, PH30/1/6928 (Tasmanian Archives Office).

Charles Tasman Ford and William Bennett Collins

The most likely candidates for the job of Woolnorth proxy during the government bounty period 1888–1909 were CT (Charles Tasman) Ford and WB (William Bennett) Collins. In the years 1891–99 Ford, a mixed farmer (sheep cattle, pigs, poultry, potatoes, corn, barley, oats) based at Norwood, Forest, near Stanley, claimed 25 bounties (23 adults and 2 juveniles), placing him in the government tiger killer top ten.[4] If you include bounty payments that appear to have been wrongly recorded as CJ Ford (5 adults, 1896) and CF Ford (1 adult, 1897), his tally climbs to an even more impressive 29 adults and 2 juveniles—lodging him ahead of well-known tiger tacklers Joseph Clifford of The Marshes, Ansons River (27 adults and 2 juveniles) and Robert Stevenson of Blessington (26 adults).[5] After Ford’s death in September 1899, Stanley storekeeper Collins claimed bounties for 40 adults and 4 juveniles 1900–06, his successful bounty applications neatly dovetailing with those of Ford.[6]

William Bennett Collins (standing at back) and family, courtesy of Judy Hick.

WB Collins’ Stanley store, AV Chester photo, Weekly Courier, 25 February 1905, p.20.

Where did their combined 75 tigers come from? The biggest source of dead thylacines in the far north-west at this time was Woolnorth. Twenty-six adult tigers were taken at Woolnorth in the years 1891–99, and 44 adults in the years 1900–06, making 70 in all. Tables 1 and 2 show rough correlations between Woolnorth killings and government bounty claims made by Ford and Collins. Ford, for example, received 7 payments 1892–93, the same figure for Woolnorth, while in the years 1894–97 his figure was 13 adults and theirs 16. Similarly (see Table 2), Collins claimed 16 adult and 4 juvenile bounties in 1900, a year in which 22 adult tigers were killed at Woolnorth; while in 1901 the comparative figures were 17 and 9. (Some of the data for Woolnorth is skewed by being recorded only in annual statements, which makes it look as though most tigers were killed in December. This was not the case: the December figures represent killings over the course of the whole year.) Clearly the Woolnorth tigers did not represent all the bounties claimed by Ford and Collins, but likely these made up the majority of their claims.

Table 1: CT Ford bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1891–99

| CT Ford |

29 – 2 |

Woolnorth |

26 – 0 |

| 31 July 1891 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 21 July 1892 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 9 Jany 1893 |

1 adult |

31 Dec 1892 |

2 adults |

| 27 April 1893 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 5 May 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 19 June 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 24 July 1893 |

1 adult |

18 Dec 1893 |

5 adults |

| 23 Jany 1894 |

2 adults |

20 Dec 1894 |

3 adults |

| 24 Feby 1896 |

5 adults |

30 Dec 1895 |

4 adults |

| 5 March 1897 |

1 adult |

7 Jany 1896 |

2 adults |

| 22 Sept 1897 |

3 adults |

19 Dec 1896 |

3 adults |

| 4 Nov 1897 |

2 adults |

Dec 1897 |

4 adults |

| 1 Feby 1898 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 2 August 1898 |

2 adults |

Dec 1898 |

3 adults |

| 30 May 1899 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

2 young |

|

|

Table 2: WB Collins bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1900–12

| WB Collins |

40 – 4 |

Woolnorth |

44 |

| 27 Feby 1900 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 16 Aug 1900 |

5 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1900 |

4 adults |

|

|

| 15 Nov 1900 |

4 adults, 4 young |

Dec 1900 |

22 adults |

| 13 Mar 1901 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 31 July 1901 |

7 adults |

|

|

| 28 Aug 1901 |

6 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1901 |

9 adults |

| 5 Nov 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1902 |

3 adults |

| 7 May 1903 |

2 adults |

Nov 1903 |

8 adults |

| 17 Nov 1903 |

4 adults |

1904 |

1 adult, 1 young (Warde) |

| 21 June 1906 |

1 adult |

1906 |

1 adult |

It would not have been difficult for Ford to act as a go-between for Woolnorth workers.[7] He had grazing land at Montagu and Marrawah/South Downs, east and south of Woolnorth respectively, and would have travelled via Woolnorth to reach the latter. He was also a supplier of cattle and other produce to Zeehan, a wheeler and dealer who bought up Circular Head produce to add to his consignments of livestock to the West Coast.[8] It would have been a simple thing for him on his way home from a Zeehan cattle drive to collect native animal skins and tiger skins/heads from the homestead at Woolnorth, presumably taking a commission for himself in his role as intermediary.

Of course that is not the only possible explanation for Ford’s bounty payments. His brothers Henry Flinders (Harry) Ford (three adults) and William Wilbraham Ford (6 adults) both claimed thylacine bounties. They had a cattle run at Sandy Cape, while William had another station at Whales Head (Temma) on the West Coast stock route.[9] It is possible that all the Ford government thylacine bounty payments represented tigers killed on their own grazing runs and/or in the course of West Coast cattle drives. CT Ford did, after all, take up land at Green Point, the place where the VDL Co killed most of its tigers in the nineteenth century. However, if the Fords killed a lot of tigers on their own properties or during cattle drives you would expect to see some evidence for it, such as in newspaper reports or letters. The Fords were, after all, not only VDL Co manager James Norton Smith’s in-laws, but variously his tenants, neighbours and fellow cattlemen. No evidence has been found in VDL Co correspondence. Oddly, when CT Ford shot himself at home in 1899, it was reported to police by his supposed employee George Wainwright—the same name as the Woolnorth tigerman of that time.[10] Perhaps this was the tigerman’s son George Wainwright junior, who would then have been about sixteen years old, and if so it shows that tigerman and presumed proxy bounty collector knew each other.

For all his 44 bounty claims, storekeeper WB Collins possibly never saw a living thylacine, let alone killed one. After Ford’s death, Collins appears to have established an on-going relationship with Woolnorth, being paid for three bounties in February 1900 before his store even opened for business. The VDL Co correspondence contains plenty of evidence that Collins dealt regularly with Woolnorth as a supplier and skins dealer.

The puzzle of Spurling’s sack of tiger heads

The only problem is Spurling. His claim about the 20 tiger heads being presented to the Stanley Police as a bounty claim doesn’t make a lot of sense. There is no record of such an event in the Stanley Police Station books, although, admittedly, tiger bounty payments rarely turn up in police station duty books or daily records of crime occurrences.[11] Still, 20 bounty claims presented at once would constitute a noteworthy event. The ‘almost W coast’ cattle station to which Spurling referred can only have been Woolnorth or a farm south of there, but his recollection seems wildly inaccurate..

If we assume Spurling got the year right, 1902, we can try to fix on an approximate date for his sack of tiger heads. Spurling photos of Stanley appeared in the Weekly Courier newspaper on 26 April 1902. If we assume that taking these photos provided the occasion for the photographer to meet the tiger heads, we are confined to government bounty payments for the first four months of that year. Less than 20 bounties were paid across Tasmania during that time, and there were no bulk payments of the kind described by Spurling—nor did any bulk payments occur at any time during the year 1902.

Did Spurling get the year wrong? If the 20 heads came from Woolnorth and were supplied in bulk, the time was probably late 1900, the first year in decades in which more than 20 tigers were taken there. Did Spurling see someone from Collins’ store bring in heads from Woolnorth? Not even that seems likely. In February 1900 Collins collected bounties for three adult thylacines; another 5 adults followed in July; in September he collected on another 4; and in October he presented 4 adults and 4 cubs: 20 animals in all, spread over a period of eight months, not in one hit.[12] Saving those 20 heads secured over a period of months for presentation in one hit would be a—frankly—disgusting task given their inevitable state of putrefaction. Spurling’s sack of heads didn’t represent Collins or Woolnorth. No one—no bounty applicant from any part of Tasmania, let alone a group of Woolnorth employees—was ever paid 20 bounties in one hit. The basis of his claim remains a mystery.

[1] See Nic Haygarth, Wonderstruck: treasuring Tasmania’s caves and karst, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.63–69.

[2] Stephen Spurling III, ‘The Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus’, Journal of the Bengal Natural History Society, vol.XVIII, no,2, October 1943, p.56.

[3] Nicholls: bounties no.289, 14 January 1889, p.127 (4 adults); and no.126, 29 April 1889, p.133 (2 adults), LSD247/1/1. Warde: bounty no.190, 20 October 1904 (1 adult and 1 juvenile), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[4] Bounties no.365, 31 July 1891 (2 adults); no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.402, 9 January 1893; no.71, 27 April 1893 (2 adults); no.91, 5 May 1893; no.125, 19 June 1893; no.183, 24 July 1893, no.4, 23 January 1894 (2 adults); no.239, 22 September 1897 (3 adults, ‘August 2’); no.276, 4 November 1897 (2 adults, ’27 October’); no.379, 1 February 1898 (‘4 December’); no.191, 2 August 1898 (2 adults, ‘7 July’); no.158, 30 May 1899 (’26 May’); no.253, 30 August 1899 (3 adults, ’24 August’); no.254, 30 August 1899 (2 juveniles, ‘24 August’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[5] Bounties no.304, 24 February 1896 (5 adults); and no.37, 5 March 1897, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[6] Bounties no.43, 27 February 1900 (3 adults, ’22 February’); no.250, 16 August 1900 (5 adults, ’26 July’); no.316, 3 October 1900 (4 adults, ’27 September’); no.398, 15 November 1900 (4 adults and 4 juveniles, ’28 October’); no.79, 13 March 1901 (2 adults, ’28 February’); no.340, 31 July 1901 (7 adults, ’25 July’); no.393, 28 August 1901 (6 adults, ‘2/3 August’); no.448, 3 October 1901 (’26 September’); no.509, 5 November 1901 (’24 October 1901’); no.218, 7 May 1903 (2 adults, ’24 April’); no.724, 17 November 1903 (4 adults); no.581, 21 June 1906, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[7] Woolnorth farm journals, VDL277/1/1–33 (TAHO). The Woolnorth figure for 1900–06 excludes one adult and one juvenile killed by Ernest Warde and for which he claimed the government bounty payment himself (bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, LSD247/1/2 [TAHO]).

[8] ‘Circular Head harvest prospects’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 19 January 1895, p.2.

[9] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1898, p.184; 1899, p.305.

[10] 10 September 1899, Daily record of crime occurrences, Stanley Police Station, POL93/1/1 (TAHO).

[11] Stanley Police Station duty book, POL92/1/1; Daily record of crime occurrences, POL93/1/1 (TAHO). Daily records of crime occurrences often include information not of a criminal nature.

[12] Bounties no.43, 22 February 1900 (three adults); no.250, 16 August 1900 (five adults); no.316, 27 September 1900 (four adults); and no.398, 28 October 1900 (four adults and four juveniles), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 22/10/20 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

By the 1890s farmers like Joseph Clifford and Robert Stevenson were effectively adding Tasmanian tiger farming to their portfolios of raising stock, growing crops and hunting. Since thylacines appeared on their property, they made a conscious effort to catch them alive in a footer snare or pit rather than dead in a necker snare. A tiger grew no valuable wool, but in 1890 a live wether might fetch 13 shillings, compared to £6 for an adult thylacine delivered to Sydney.[1] A dead adult thylacine, on the other hand, was worth only £1 under the government bounty scheme.

The problem with these special efforts to catch tigers alive was that hunters only had a certain amount of control over what animals ended up in their snares or pits. Twentieth-century hunters often complained about city regulators who thought it feasible to close the season on brush possum but open it for wallabies and pademelons. Inevitably, hunters caught some brush possum in their wallaby and pademelon snares during the course of the season, which could land them a hefty fine in court unless they destroyed the precious but unlawful skins.[2] John Pearce junior in the upper Derwent district claimed that he and his brothers caught seventeen tigers in ‘special neck snares’ set alongside their kangaroo snares.[3] How did the tigers recognise the ‘special neck snares’ provided for their specific use? All you could do was vary the height of the necker snare to catch the desired animal’s head as it walked. Too bad if something else stuck its head in the noose. Wombats, for example, were a hazard. Gustav Weindorfer of Cradle Valley set snares at the right height to catch Bennett’s wallabies by the neck, but also caught wombats in them.[4] Wombats were good for ‘badger’ stew and for hearth mats but the skins had no value. Robert Stevenson of Aplico, Blessington, caught wombats alive in his tiger pits—which they then set about destroying by burrowing their way out.[5]

George Wainwright senior, Matilda Wainwright and children at Mount Cameron West (Preminghana) c1900. Courtesy of Kath Medwin.

These problems aside, it seems odd that the pragmatic Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co), which later added fur hunting to its income stream, didn’t cotton on to the live tiger trade. They could have followed the example of George Wainwright senior, who sold a Woolnorth tiger to Fitzgerald’s Circus in 1896.[6] In 1900, for example, 22 thylacines were killed on Woolnorth, a potential income of more than £100 had the animals been taken alive. Even when, later, four living Woolnorth tigers were sold, the money stayed with the employees, with the VDL Co not even taking a commission. (It should be noted that four young tigers caught by Walter Pinkard on Woolnorth in 1901 were not accounted for in bounty payments.[7] It is possible that they were sold alive—but there are no records of a sale or even correspondence about the animals. Their fate is unknown.)

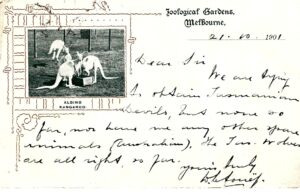

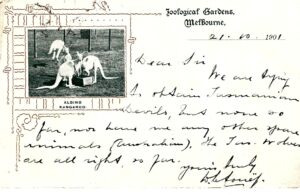

William Le Souef to Kruger, 22 October 1901: ‘The Tasmanian Wolves are all

right, so far’. Did he get them from Woolnorth? Postcard courtesy of Mike Simco.

The VDL Co’s failure to exploit the live trade for its perceived arch enemy can possibly be explained by the tunnel vision of its directors and departing Tasmanian agent and the inexperience of his successor. James Norton Smith resigned as local manager in 1902. His replacement, Scotsman Andrew Kidd (AK) McGaw, harnessed Norton Smith’s 33-year corporate knowledge by re-engaging him as farm manager. It would not have been easy for McGaw to learn the ropes in a new country, among business associates cultivated by his predecessor, and the re-engagement of Norton Smith as his second allowed him to transition into the manager position. As would be expected, McGaw stamped his authority on the agency by criticising some of Norton Smith’s policies and distancing himself from them.[8] Ahead of Ernest Warde’s engagement as ‘tigerman’, the VDL Co’s shepherd at Mount Cameron West, he scrapped Norton Smith’s recent bounty incentive scheme of £2 for a tiger killed by a man out hunting with dogs.

Woolnorth, showing main property features and the original boundary. Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

After Warde’s departure in 1905, the tiger snares at Mount Cameron and Studland Bay were checked intermittently. Woolnorth overseer Thomas Lovell killed a tiger at Studland Bay in 1906, but the number of tigers and dogs reported on the property was now negligible.[9] This reflected the statewide situation, with only eighteen government thylacine bounties being paid in 1907, and only thirteen in 1908.[10]

However, the value of live tigers continued to climb as they became rarer. The first documented approach to the VDL Co for live tigers came in July 1902 from AS Le Souef of the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne, who offered £8 for a pair of adults and £5 for a pair of juveniles. He also wanted devils and tiger cats, in response to which George Wainwright junior supplied two tiger cats (spotted quolls, Dasyurus maculatus).[11] Given the tiger’s reputation as a sheep killer, native animal farming might have been a hard sell to the directors, and the company continued to use necker snares which were generally fatal to thylacines. What price would it take to change that behaviour? In July 1908 McGaw read a newspaper advertisement:

‘WANTED—Five Tasmanian tigers, handsome price for good specimens. Apply Beaumaris, Hobart.’[12]

He discovered that the proprietor of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point, Mary Grant Roberts, wanted a pair of living tigers immediately to freight to the London Zoo.[13] The Orient steamer Ortona was departing for London at the end of the month. She offered McGaw £10 for a living, uninjured pair of adults. Roberts hoped to secure the tiger caught recently by George Tripp at Watery Plains, but felt that she was competing for live captures with William McGowan of the City Park Zoo, Launceston, who advertised in the same month.[14] Eroni Brothers Circus was also in the market for living tigers.[15]

A young Mary Grant Roberts, from NS823/1/69 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

Almost as Roberts made her offer, George Wainwright junior tracked a tiger at Mount Cameron West, but it evaded capture.[16] In the meantime Roberts was able to secure her first thylacine from the Dee River.[17]

Almost a year passed before the chance arose for the VDL Co do business, when in May 1909 Wainwright retrieved a three-quarters-grown male tiger uninjured from a necker snare.[18] Perhaps not appreciating the tiger’s youth, Roberts offered £5 plus the rail freight from either Burnie or Launceston. She wanted the animal delivered to her in Hobart within ten days in order to ship it to the London Zoo on the Persic. It would thereby replace one which had died of heat exhaustion in transit to the same destination a few months earlier.[19]

However, the overseer of a remote stock station could not meet that deadline. The delay came with a bonus—the capture of three more members of the first tiger’s family, his sisters and mother.[20] Bob Wainwright recalled his stepfather Thomas Lovell and brother George placing the animals in a cage. There was also a familiar story of tigers refusing to eat dead game: ‘They had to catch a live wallaby and throw it in, alive, and then they [the thylacines] killed it’.[21] With McGaw continuing to act as intermediary between buyer and supplier, a price of £15 was settled on for the family of four.[22]

Roberts and McGaw communicated as social equals, but their social inferiors—hunters, stockmen and an overseer—were not named in their correspondence. This made for frustrating reading when Roberts discussed hunters (‘the man’) with whom she was dealing over live tigers. She had been expecting to receive two young tigers from a Hamilton hunter for her own zoo, but these had now died, causing her to reconsider her plans for the Woolnorth family.[23]

The mother thylacine (centre) and her three young captured at Woolnorth in 1909. W Williamson photo from the Tasmanian Mail, 25 May 1916, p.18.

It wasn’t until the first week in July 1909 that the auxiliary ketch Gladys bore the crate of thylacines to Burnie, where they began the train journey to Hobart.[24] A week later they were said to be thriving in captivity.[25] Roberts was so pleased with the animals’ progress that after eight months she sent a postal order to Lovell and Wainwright as a mark of appreciation. She was impressed with the mother’s devotion to her young, believing that the death of the two Hamilton cubs was attributable to their mother’s absence.[26] However, money was becoming a concern. Buying all the tigers’ feed from a butcher was expensive, and when she received a potentially lucrative order for a tiger from a New York Zoo, she found the cost of insuring the animal over such a long journey prohibitive. On 1 March 1910 she ‘very reluctantly’ broke up the family group by dispatching the young male to the London Zoo. ‘I am keeping on the two [other juveniles]’, she wrote, ‘in the hope that they may breed, and the mother all along has been very happy with the three young ones’.[27]

Roberts was now offering £10 per adult thylacine—but there was none to sell at Woolnorth. Seventeen months later she paid Power £12 10s for his large tiger from Tyenna, and scored £30 shipping to London the last of the three young from the 1909 family group.[28] Her tiger breeding program was over, probably defeated by economics—but what might have been the rewards for perseverance? Perhaps she would have been the greatest tiger farmer of all.

[1] See, for example, ‘Commercial’, Mercury, 5 August 1890, p.2; Sarah Mitchell diary, 9 June 1890, RS32/20, Royal Society Collection (University of Tasmania Archives).

[2] See, for example, ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[3] ‘Direct communication with the west coast initiated’, Mercury, 1 September 1932, p.12.

[4] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Journal of the Victorian Naturalists Society, vol.36, March 1920, p.159.

[5] Lewis Stevenson, interviewed by Bob Brown, 1 December 1972 (QVMAG).

[6] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[7] Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 19 July 1901, VDL22/1/27 (TAHO).

[8] In Outward Despatch no.46, 4 January 1904, p.366, McGaw criticised Norton Smith for not doing more to arrest the encroachment of sand at Studland Bay and Mount Cameron (VDL7/1/13).

[9] Woolnorth farm diary, 30 September 1906 (VDL277/1/34). This VDL Co bounty was not paid until the following year (December 1907, p.95, VDL129/1/4). C Wilson was paid for killing two dogs found worrying sheep in 1906 (December 1906, p.58, VDL129/1/4 (TAHO).

[10] See thylacine bounty payment records in LSD247/1/3 (TAHO).

[11] AS Le Souef to James Norton Smith, 11 July 1902; Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 4 August 1902, VDL22/1/28 (TAHO).

[12] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 July 1908, p.3.

[13] For Roberts, see Robert Paddle, ‘The most photographed of thylacines: Mary Roberts’ Tyenna male—including a response to Freeman (2005) and a farewell to Laird (1968)’, Australian Zoologist, vol.34, no.4, January 2008, pp.459–70.

[14] In ‘Wanted to buy’, Mercury, 18 July 1908, p.2, McGowan asked for tigers ‘dead or alive’. He had also advertised for ‘tigers … good, sound specimens, high price; also 2 or 3 dead or damaged specimens’ in the previous year (‘Wanted’, Mercury, 21 June 1907, p.2). George Tripp’s tiger must have died before it could be sold alive, since he claimed a government bounty for it (no.35, 25 July 1908, LSD247/1/3 [TAHO]).

[15] See, for example, ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 March 1908, p.6.

[16] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 17 July 1908, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[17] ‘The Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 7 October 1908, p.4.

[18] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 24 May 1909, VDL22/135 (TAHO). This thylacine was originally thought to be a young female, but McGaw later stated that it was a young male.

[19] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 31 May 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[20] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 1 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[21] Bob Wainwright, 86 years old, interviewed in Launceston, 27 October 1980.

[22] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 9 June 1909, VDL52/1/29; Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 10 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[23] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 21 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[24] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 7 July 1909, VDL52/1/29 (TAHO); ‘Stanley’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 July 1909, p.2.

[25] W Roberts to AK McGaw, 15 July 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[26] In May 1912 she received two young tigers from buyer EJ Sidebottom in Launceston, paying him £20 in the belief that they were adults. They died three days later (Mary Grant Roberts diary, 6, 7 and 10 May 1912, NS823/1/8 [TAHO]).

[27] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 14 March 1910, VDL22/1/36 (TAHO).

[28] Mary Grant Roberts diary, 12 August, 26 September and 24 December 1911, NS823/1/8 (TAHO).