At Pisa Cemetery the Parkers, O’Connors, Gatenbys and Smiths are all equals. Some of course are more equal than others, having large, decorated headstones and obelisks, but their bones moulder in the same clay and their spirits, should they have any, mingle on the same windswept plain rolling back to the blue profile of the Great Western Tiers. It is remarkable that the graves of John (c1822–1903) and Hannah Jane Smith (c1819–1903) are marked at all. It doesn’t get more anonymous than being John Smith, and the anonymity of a bare patch between the plinths of their betters awaited most of the likes of these two. Perhaps their old employer Roderic O’Connor (1849–1908) gave them a monument as a mark of respect.

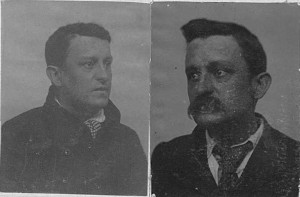

The irony of that action wouldn’t have been lost on John Smith, one of 314 bearers of that name conscripted to Van Diemen’s Land. A native of Nottingham, Jack was a single, semi-literate, 170-cm-tall labourer when sentenced to 7 years’ transportation for stealing a pair of shoes and a hatchet as a 20-year-old in 1842. The hatchet was a token of a combative life. He had a prior conviction and five short prison terms under his belt, being, apparently, ‘a bad irreclaimable lad, connected to other lads who live by plunder’. Transported on the Forfarshire, he appears to have laboured in a probation gang at Westbury before his attempts to abscond landed him in the Port Arthur Gaol. Jack spent 3½ years in the probation system, enduring 179 lashes, 88 days of solitary confinement and 21 months of hard labour in chains before being released for private service in 1847 at the age of about 25. What would his opinion have been at that time about whether transportation was a sentence or an opportunity?

Jack then worked for Edward Archer of Northbury, Longford (nearly two years), and Joseph Oakley of Oatlands, achieving freedom by servitude at the expiry of his sentence in 1849.[1]

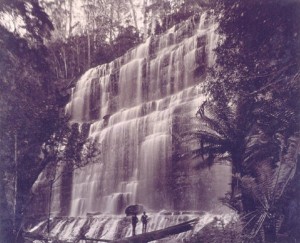

Perhaps he still brandished that hatchet, because within a few years Jack was living by plunder once more, working out of a hide-out near Millers Bluff. Known as ‘Jack the Hunter’, in the mould of the Irish outlaw ‘Jack the Shepherd’, he was accused of rustling sheep from the large properties adjoining the slopes of the Great Western Tiers. In 1856 graziers Arthur O’Connor of Connorville and Charles Parker of Parknook tracked him down and sent a volley his way. Jack raised his weapon at O’Connor but it failed to discharge, and he made his escape.[2] The threat Jack posed to wool-growing was raised in parliament.[3] An armed police party sent to apprehend him mistakenly pounced on a roving entomologist at the Hummocky Hills.[4] A posse led by District Constable Thomas Kidd of George Town did better, finally arresting Jack the Hunter or ‘Hellfire Jack’[5] at Hells Bottom on the slopes of Millers Bluff in 1858. Here they also found the evidence of his ovine crimes in a veritable maze of hideouts, including an underground wool store. Jack was shot in the arm while trying to escape, newspaper reports varying in their accounts of his injuries.[6] His victims, the Gatenbys and O’Connors, secured two of his hunting dogs as a form of recompense.[7] The ex-convict was sentenced to four years’ gaol for stealing 15 sheep worth £8 from George Gatenby of Barton.[8]

In 1870 a newspaper writer recounting Jack’s tale commented that ‘Poor Jack, now in confinement, must look back with harrowing regret to his wild hut high on the tier’.[9] In fact Jack was already back on the tier.[10] Somehow Arthur O’Connor had forgiven his depredations and allowed him back onto Connorville—presumably as a shepherd! After all, there’s no substitute for local knowledge. Jack’s residence was Boomers Bottom, a sheep run where the Lake River cut a passage down through the mountains. Adam Jackson’s 1847 survey of the upper Lake River didn’t recognise Hells Bottom but mapped Scrubby Den and the even more tantalising Tigers Bottom.

Jack was certainly at Connorville in 1885 when ‘Jimmy the Sailor’ Casey saved his five-year-old from drowning in the mill race.[11] But Jack was more than a father and a hunter: he was a serial thylacine decapitator. He buried his hatchet in tigers’ necks. The submission of severed animal heads to unsuspecting public officials sounds like something out of The Godfather.[12] However, this seems to have been acceptable behaviour at the time. At least twelve thylacine heads were presented to the Longford warden or police office for payment in the years 1888–97, Connorville and Parknook being star killing fields.[13] Jack produced eight of these, probably securing them in necker snares.[14] In 1897 he claimed to have killed about 130 tigers during 30 years’ residence at Boomers Bottom.[15] It is possible that Jack managed a line of necker snares across a gully through which tigers were thought to be entering the Connorville property, in the fashion of the Woolnorth ‘tigerman’ at Green Point in the far north-west. Even so, four tigers per year hardly constitutes an invasion, and we do not know if any of those 130 savaged any of Connorville’s 14,000-strong grazing flock.[16]

Jack’s partner Hannah Jane Smith predeceased him by nine months.[17] Her story, like those of so many other anonymous wives and female partners, is unknown. Their child or children are also untraceable, their births seemingly evading the registrar. Perhaps Hannah helped Jack secure his sixteen £1 government tiger bounties.[18] That would have paid for some sugar, tea, tobacco and snaring hemp or wire but not saved them from kangaroo leather ensembles and a diet of macropod and potato. Perhaps Jack’s hunting was a lot more lucrative than that in the backblocks of Connorville. Perhaps Jack and Hannah lived at a distance in mutual contempt. We will never know. They keep their secrets beneath the loam at St Mark’s, Lake River, where the tigers once roamed.

[1] Conduct record for John Smith per Forfarshire, CON33/1/44, p.197 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA), https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON33-1-44/CON33-1-44p197; Conduct record for John Smith per Forfarshire, CON37/1/9, image 216 (TA), https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON37-1-9, both accessed 4 August 2024.

[2] ‘Bushranging’, Launceston Examiner, 18 September 1856, p.3.

[3] ‘House of Assembly—last night’, Courier, 9 October 1858, p.2.

[4] ‘An Old Vet’, ‘Jack the Hunter: an episode in a VDL policeman’s life’, Daily Telegraph, 4 January 1895, p.6.

[5] ‘Capture of another bushranger’, Courier, 8 October 1858, p.3. ‘Hellfire Jack’ was also the nickname of the ex-convict John Snelson.

[6] ‘Bushranging in Tasmania’, Courier, 8 October 1858, p.3.

[7] George Gatenby diary, 31 August and 1 September 1858, NS1255/1/1 (TA).

[8] ‘Oatlands Supreme Court’, Hobart Town Advertiser, 3 January 1859, p.7.

[9] ‘Aegles’, ‘Notes in north Tasmania’, Launceston Examiner, 15 February 1870, p.5 (reprinted from the Leader [Melbourne]).

[10] ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[11] ‘Cressy’, Mercury, 22 September 1885, p.4.

[12] The Godfather, a 1972 movie directed by Francis Ford Coppola, included a scene in which a severed horse’s head was placed in the bed of a sleeping man.

[13] Longford notes’, Launceston Examiner, 2 August 1888, p.5; ‘Longford notes’, Launceeston Examiner, 2 July 1889, p.4; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 13 March 1890, p.3; ‘Longford’, Mercury, 4 October 1890, p.2; ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 30 September 1891, p.2; ‘Country intelligence’, Tasmanian, 27 August 1892, p.30; ‘Longford’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1893, p.2; ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[14] ‘Longford’, Launceston Examiner, 13 March 1890, p.3; ‘Longford notes’, Tasmanian, 4 October 1890, p.22; ‘Country intelligence’, Tasmanian, 27 August 1892, p.30; ‘Longford’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1893, p.22;

[15] ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[16] The size of the sheep flock is from E Richall Richardson, ‘A tour through Tasmania (letter no.73): Connorville’, Tribune, 12 November 1877, p.2.

[17] Headstone, Pisa Cemetery.

[18] Bounties no.582, 17 December 1889; no.81, 18 March 1890; no.354, 20 August 1890; no.463, 7 October 1890; no.62, 26 March 1891; no.184, 22 May 1891; no.822, 1 April 1892; no.272, 12 September 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.123, 19 June 1893 (2 adults); no.13, 5 March 1895; no.37, 30 [sic] February 1896; no.39, 5 March 1897 (3 adults); no.45, 17 March 1898 (‘2 March’), LSD247/1/2 (TA).