by Nic Haygarth | 28/08/21 | Story of the thylacine

One of north-eastern Tasmania’s greatest hunters was Joseph Clifford (1856–1932), a bush farmer at The Marshes, on Ansons River.[1] Clifford was an incidental snarer of tigers who cottoned onto the live tiger trade as they grew scarcer and more valuable. He was born to ex-convict farmer John Clifford (c1822–1919) and bounty immigrant Mary Ann Lock (aka Anne Viney, c1828–94) at Georges Bay (St Helens).[2] In 1879, as an illiterate 23-year-old farmer, Joseph married 20-year-old farmer’s daughter Emma Summers (c1859–1937).[3] Their four sons and two daughters grew up at The Marshes, where the marshland stretched along both sides of the Anson River and the herbage was plentiful for the stock.[4]

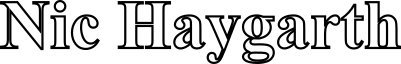

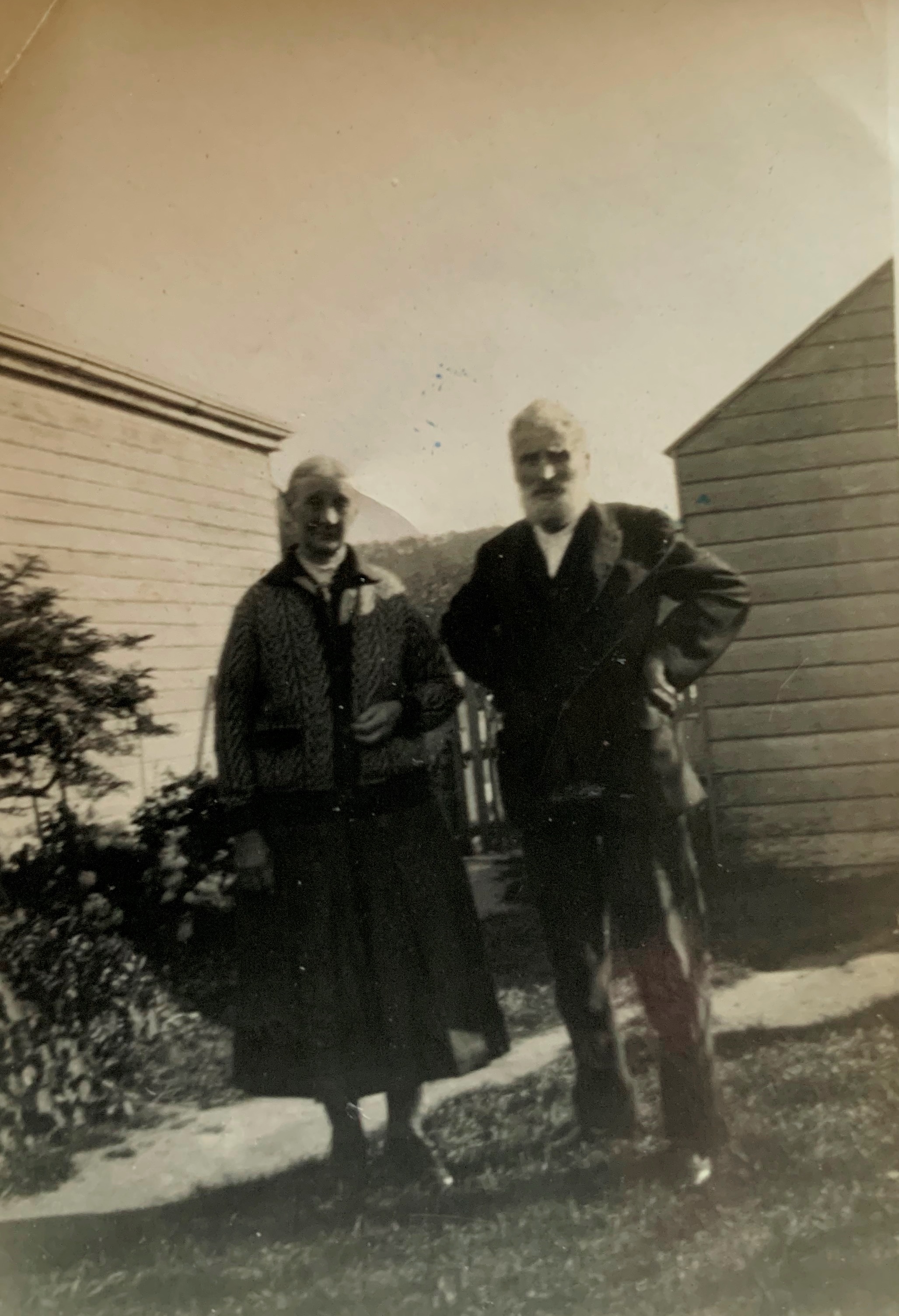

A young Joseph Clifford, courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

Emma and Joseph Clifford at The Marshes, courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

Tigers were also relatively plentiful. In August 1889 a ‘case of native tigers’ was shipped out of Boobyalla to Launceston on the coastal trader Dorset.[5] It was a mother and three cubs destined for William McGowan, manager of the zoo in Launceston’s City Park, who received 21 live thylacines, mostly from the north-east, between June 1885 and July 1893.[6] Perhaps some of them came from Grodens Marsh, across the river from the house at The Marshes. Here Joseph Clifford claimed to have seen a tiger sneak amongst the sheep in order to kill a lamb. He believed that tigers struck the sheep at dusk or dawn, particularly in foggy conditions, taking motherless lambs and any weak ewes. He claimed to have seen as many as nine tigers at one time and developed the belief that they hunted in packs. When the working dogs dragged their chains into their kennels with fear, Joseph released the so-called staghounds, hunting dogs, to tackle the interlopers.[7] These dogs were a mix of great Dane and greyhound, and while used chiefly in possuming they had no fear of tigers.[8]

The Marshes, Ansons River, as it looked from the air in 1969, when the old home and barn still stood. At centre left, across the river from the house, is Grodens Marsh. From aerial photo 528_161, courtesy of DPIPWE.

On one occasion, at a place called the Thomas, Joseph came across five tigers chasing a bandicoot. Most of his staghounds pursued the group, but one dog went after a tiger that broke away on its own. His third son Harry Clifford (c1891–1974) recalled that:

‘When he [Joseph] got down to where the other two [the lone dog and the lone tiger] was they was [sic] both standing up on their hind legs like two dogs fighting’.[9]

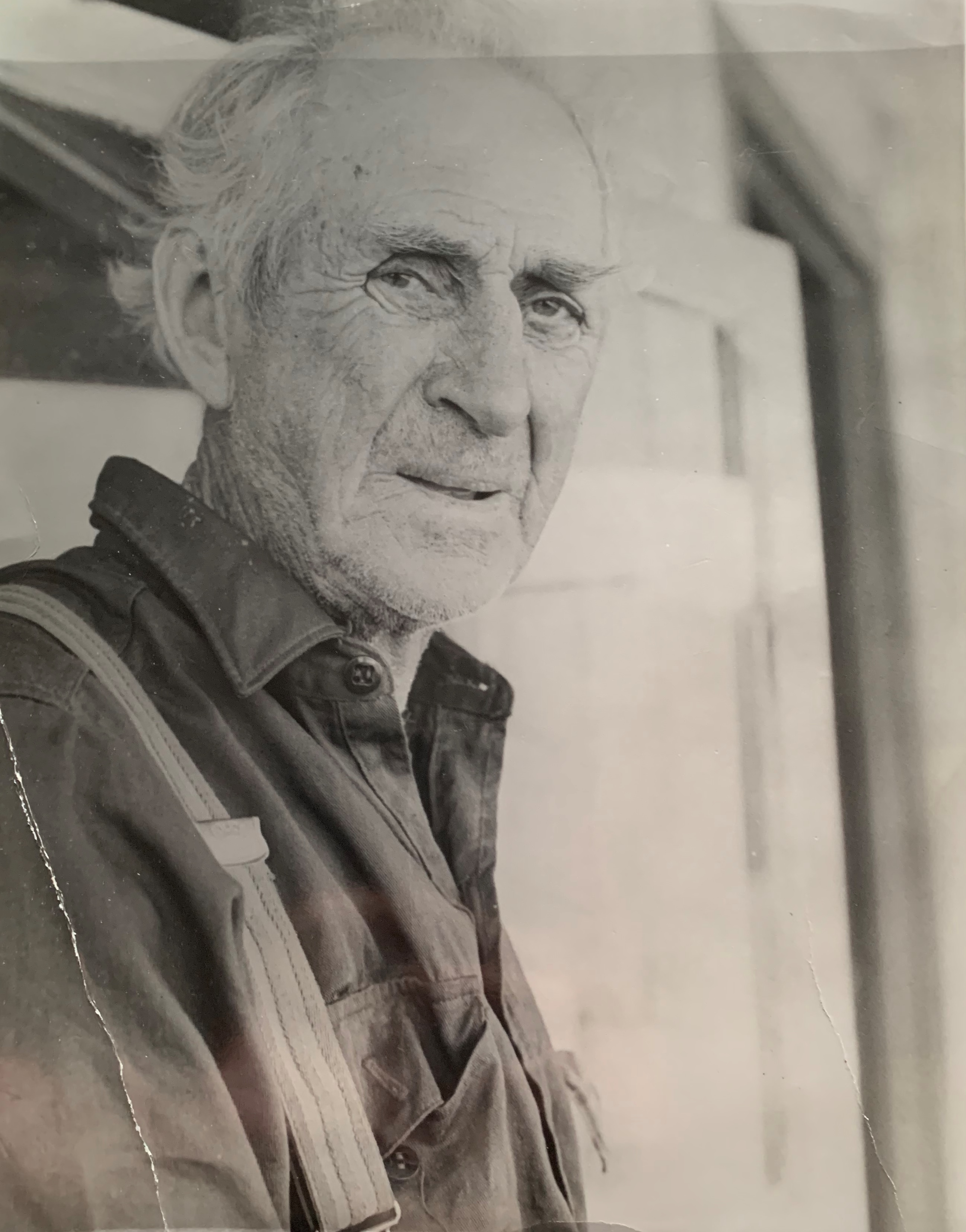

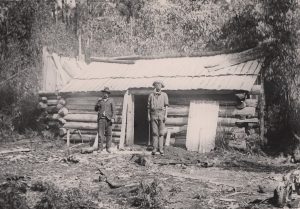

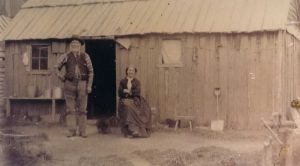

The old house at The Marshes, courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

Harry and Emma, his mother, were both scared of tigers. Harry recalled his mother telling him that she saw tigers killing their sheep. One time as Joseph arrived home from a hunting trip, Emma said, ‘Oh the tigers have been here again after the sheep.’ ‘Why didn’t you let the dogs loose?’, Joseph replied. ‘Of course’, said Harry, looking back, ‘she was too scared to go out’. On another occasion when the dogs were let loose they ran down a tiger at Dead Horse Creek, east of the homestead. Harry recalled that ‘the next day the others [other tigers] set up in the little paddock down there howling like dogs’, as if lamenting a missing family member.[10]

Joseph claimed government bounties for perhaps 27 adult and 2 juvenile thylacines (worth £28) in the period 1892–1903, including at least 5 adults in 1897.[11] These would have been incidental killings in the course of landing thousands of kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons and brush and ringtail possums. Snaring was essential to the survival of many poor bush families, and the temptation to snare illegally out of season, tanning skins to sell locally, was strong. In 1905 Joseph suffered a serious setback when a zealous constable found a stash of 337 possum skins and some kangaroo skins concealed under a hay stack at The Marshes out of season, for which he was fined a very hefty £59 17 shillings.[12] He would have needed a very good legal hunting season to make up for it.

The switch to the live tiger trade

While the demand for live tigers was low, there was insufficient inducement for some hunters to undertake the considerable trouble involved in keeping them alive and getting them to market. Sarah Mitchell of Lisdillon near Swansea, for example, was offered £6 for a live tiger by the Sydney Zoological Society in 1890 but ended up £5 out of pocket when it died in transit.[13]

The price of a live tiger had probably increased by 1901, when Joseph Clifford brought a thylacine threesome home on the back of a horse, apparently having snared the mother without killing her.[14] He kept the mother and two pups in a barn at The Marshes, with the idea of selling them, but he couldn’t get them to eat. He caught live native hens and wallabies to feed them but the captives took no interest. Finally the thylacine family starved to death, leaving Joseph to claim £2 for presentation of their carcasses under the government bounty scheme and whatever additional money he could get for the skins themselves.[15]

The barn at The Marshes in which Joseph Clifford kept the live tigers. Harry Clifford is the man in the hat. Photo courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

This incident brought about a change in thinking. Joseph originally used necker snares, with the intention of killing his prey, but now he switched over to footer or treadle snares in order to spare tiger lives and collect a bigger prize.[16] Reasoning that thylacines might survive longer in something resembling their natural habitat, he built an enclosure for them on a marsh at nearby Wurrawa. It was a chicken-wire pen about six metres long by two wide, with tall timber posts.[17] It was here that Harry Clifford remembered his father teaching him, as a teenager, to immobilise a tiger by grabbing its tail from behind and lifting its hind quarters off the ground.[18] How many live tigers the Cliffords caught in the early 1900s and who they sold them to is unknown. The most likely recipient is William McGowan of Launceston’s City Park Zoo, who received six tigers June 1898–June 1901 (three of those are known to have come from the Great Western Tiers), and another 24 June 1901–February 1906.[19] Mary Grant Roberts of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point in Hobart also started buying tigers in 1909, followed by James Harrison of Wynyard in 1910, but as mentioned previously there were also mainland buyers.

Harry Clifford’s tiger experiences

Harry Clifford saw at least fifteen tigers during the first half of his life, without even going out of his way.[20] ‘We didn’t go shooting tigers’, he asserted. ‘They came to us’, that is, they entered the Clifford property and ended up in Clifford snares mostly set for other animals. However, Harry did set two tiger traps at The Marshes, both like heavy duty rabbit traps. He placed one on a crossing log on the Anson River, a typical setting for a snarer, but it seems he never landed his intended prey.

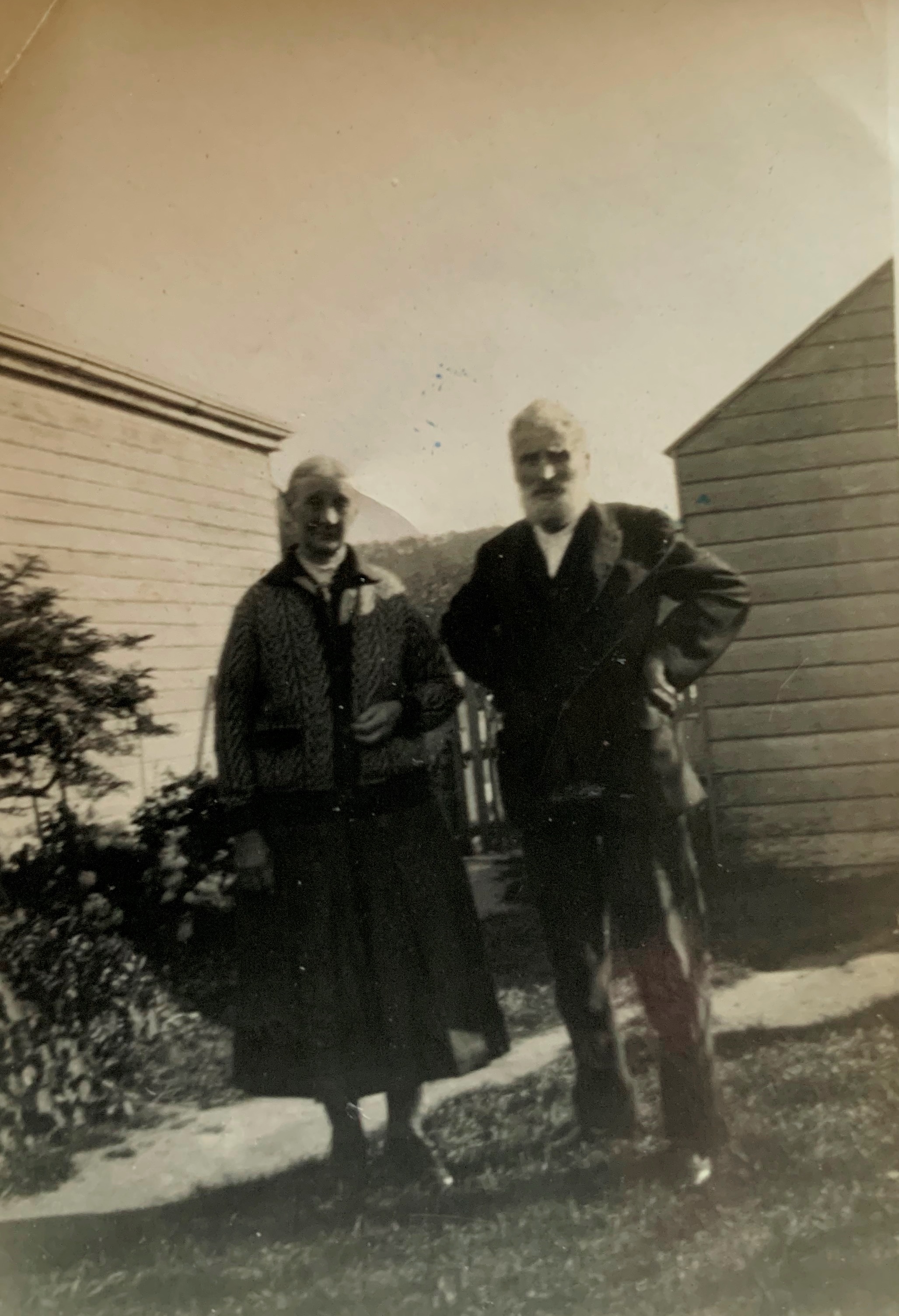

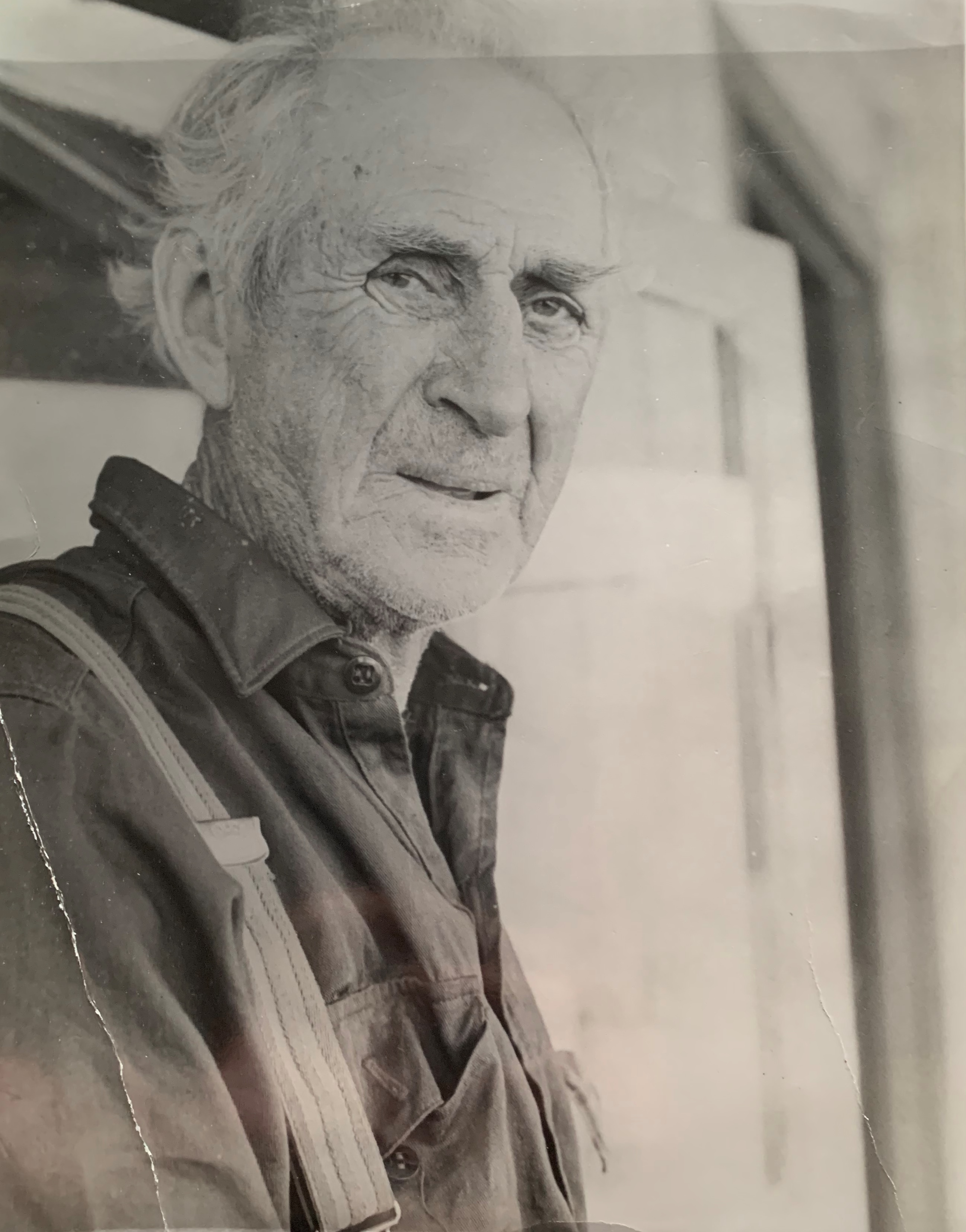

Harry Clifford, photo courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

On one occasion while snaring Harry Clifford met a female tiger on a track. He had just slung a wallaby over his shoulder which he had taken out of a snare. As he advanced towards the next snare his dogs grew excited and began to retreat behind him, betraying what lay ahead. Harry was not the first person to assert that a tiger on a track would not move out of the way of a human.[21] The female sat steadfastly on the track ahead of him. Guessing that the object of her interest was the large slab of fresh meat on his shoulder, he slowly lowered it to the ground in front of him and backed off. As the tiger grabbed the wallaby, three pups emerged from the scrub to feed. Next day when Harry returned only the skeleton of the wallaby remained.

Harry believed that a thylacine would rip a hole in a sheep under the front leg where there was no wool and bore a hole into the rib cage in order to eat the internal organs. It would eat the kidneys, heart and lungs, and also take the meat off the back legs. A tiger, he said, could eat bandicoots and rabbits whole. It would catch bandicoots in tussocks, pouncing like a cat nose first, holding the tussock with its front paws as it pulled the prey out with its teeth.[22]

[1] ‘Priory: late Mr Joseph Clifford’, Examiner, 16 November 1932, p.5.

[2] Born 2 January 1856, birth record no.276/1856, registered at Fingal, RGD33/1/34 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=joseph&qu=clifford#, accessed 22 April 2019. For John Clifford as a convict, see marriage permission 31 March 1848, CON52/1/2, p.307 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=clifford&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriage+Permissions%09Marriage+Permissions, accessed 22 April 2019.

[3] Married 15 December 1879, marriage record no.656/1879, married at Georges Bay, registered at Portland, RGD37/1/38 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=joseph&qu=clifford, accessed 22 April 2019. Emma Clifford died 17 November 1937, aged 78, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery. The four sons were Joseph (born 1880), John (‘Ginger Jack’, born 1889), Henry (Harry, c1891–1974), James (1893–1920). The two daughters were Emma Ann Jane (born 1896) and Amy Florence (‘Florrie’) (1899–1923).

[4] ‘Priory: late Mr Joseph Clifford’, Examiner, 16 November 1932, p.5. Henry (Harry) Clifford died 19 November 1974, aged 83, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery. See will no.60025, AD960/1/151 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=henry&qu=clifford&isd=true, accessed 10 June 2020. James Clifford died 25 June 1920, aged 26, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery.

[5] ‘Shipping intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 19 August 1889, p.2.

[6] ‘Local and general’, Tasmanian, 24 August 1889, p.23; Robert Paddle, ‘The thylacine’s last straw: epidemic disease in a recent mammalian extinction’, Australian Zoologist, vol. 36, no.1, 2012, p.76.

[7] ‘Anson Marshes’, Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1922, p.6; Clifford family information from Deb Groves, 16 November 2019.

[8] John Morling, St Helens, interviewed by Deb Groves, 2019.

[9] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[10] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970.

[11] That is, 15 adults and 2 juveniles in the name of Josh Clifford, and 12 adults in the name of J Clifford. Josh Clifford: bounties no.283, 21 September 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.30, 6 March 1893; no.251, 16 October 1893 (2 adults); no.177, 10 July 1897 (5 adults); no.336, 23 November 1898 (‘5 November’); no.375, 12 January 1899 (‘5 December’); no.88, 27 April 1899 (’15 April’); no.375, 5 December 1899 (’13 November’); no.436, 27 September 1901 (1 adult and 2 juveniles, ’26 August’); no.354, 23 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO). J Clifford: bounties no.734, 11 January 1892; no.118, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.160, 5 July 1893 (2 adults); no.185, 10 October 1895 (2 adults); no.338, 31 July 1901 (5 adults, ’10 July’); no.984, 25 July 1902 (‘9 June’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO). For Joseph Clifford’s 1897 tiger killings see ‘The country’, Daily Telegraph, 22 April 1897, p.4; ‘St Helens’, Daily Telegraph, 23 August 1897, p.3; ‘St Helens’, Mercury, 27 August 1897, p.3.

[12] ‘Gladstone’, Examiner, 7 March 1905, p.6; ‘A heavy fine’, Examiner, 27 March 1905, p.5.

[13] Sarah Mitchell diary, 17 and 19 May, 9 and 26 June 1890 (University of Tasmania Special Collections).

[14] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[15] Jeff Richards, nephew of Harry Clifford; interviewed by Deb Groves. Jeff remembered Harry specifying that there were four or five young with the mother.

[16] John Morling, St Helens, interviewed by Deb Groves, 2019.

[17] Clifford family information from Deb Groves, 16 November 2019.

[18] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[19] Robert Paddle, ‘The thylacine’s last straw …’, pp.76 and 81.

[20] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[21] See Robert Stevenson to David Cunningham, 13 November 1941, QVM1/59, part 4, Inward correspondence 1941 (QVMAG). The same incident was reported in ‘Adventure with a native tiger’, Launceston Examiner, 22 March 1899, p.5.

[22] Harry Clifford, interviewed by Deb Groves, c1970.

by Nic Haygarth | 18/04/20 | Tasmanian high country history

When 52-year-old Maria Francis died of heart disease at Middlesex Station in 1883, Jack Francis lost not only his partner and mother to his child but his scribe.[1] For years his more literate half had been penning his letters. Delivering her corpse to Chudleigh for inquest and burial was probably a task beyond any grieving husband, and the job fell to Constable Billy Roden, who endured the gruesome homeward journey with the body tied to a pack horse.[2]

Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

By then Jack seems to have been considering retirement. He had bought two bush blocks totalling 80 acres west of Mole Creek, and through the early 1890s appears to have alternated between one of these properties and Middlesex, probably developing a farm in collaboration with son George Francis on the 49-acre block in limestone country at Circular Ponds.[3]

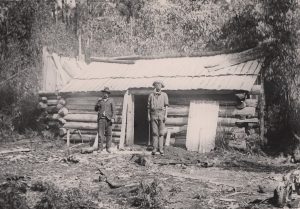

Jack Francis and second partner Mary Ann Francis (Sarah Wilcox), probably at their home at Circular Ponds (Mayberry) in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of Shirley Powley.

Here Jack took up with the twice-married Mary Ann (real name Sarah) Wilcox (1841–1915), who had eight adult children of her own.[4] Shockingly, as the passing photographer Frank Styant Browne discovered in 1899, Mary Ann’s riding style emulated that of her predecessor Maria Francis (see ‘Jack the Shepherd or Barometer Boy: Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis’). However, Mary Ann was decidedly cagey about her masculine riding gait, dismounting to deny Styant Browne the opportunity to commit it to posterity with one of his ‘vicious little hand cameras’.[5]

Perhaps Mary Ann didn’t fancy the high country lifestyle, because when Richard Field offered Jack the overseer’s job at Gads Hill in about 1901 he took the gig alone.[6] This encore performance from the highland stockman continued until he grew feeble within a few years of his death in 1912.[7]

Mary Ann seems to have been missing when the old man died. Son George Francis and Mary Ann’s married daughter Christina Holmes thanked the sympathisers—and Christina, not George or Mary Ann, received the Circular Ponds property in Jack’s will.[8] Perhaps Jack had already given George the proceeds of the other, 31-acre block at Mole Creek.[9]

Field stockmen Dick Brown (left) and George Francis (right) renovating the hut at the Lea River (Black Bluff) Gold Mine for WM Black in 1905. Ronald Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

By the time Mary Ann Wilcox died in Launceston three years later, George Francis had long abandoned the farming life for the high country. He was at Middlesex in 1905 when he renovated a hut and took part in the search for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain.[10] Working out of Middlesex station, he combined stock-riding for JT Field with hunting and prospecting.

Like fellow hunters Paddy Hartnett and Frank Brown, Francis lost a small fortune when the declaration of World War One in July 1914 closed access to the European fur market, rendering his winter’s work officially worthless. At the time he had 4 cwt of ‘kangaroo and wallaby’ (Bennett’s wallaby and pademelon) and 60 ‘opossum’ (brush possum?). By the prices obtaining just before the closure they would have been worth hundreds of pounds.[11] Sheffield Police confiscated the season’s hauls from hunters, who could not legally possess unsold skins out of season.

The full list of skins confiscated by Sheffield Police on 1 August 1914 gives a snapshot of the hunting industry in the Kentish back country. Some famous names are missing from the list. Experienced high country snarer William Aylett junior was now Waratah-based and may have been snaring elsewhere.[12] Bert Nichols was splitting palings at Middlesex by 1914 but may not have yet started snaring there.[13] Paddy Hartnett concentrated his efforts in the Upper Mersey, probably never snaring the Middlesex/Cradle region. His double failure at the start of the war—losing his income from nearly a ton of skins, and being rejected for military service—drove him to drink.[14]

‘Return of skins on hand on the 1st day of August [1914] and in my possession’, Sheffield Police Station.

| Name |

Location |

Kangaroo/wallaby |

Wallaby |

Possum |

| George Francis |

Msex Station |

448 lbs |

|

60 skins |

| Frank Brown |

Msex Station |

562 skins+ 560 lbs |

|

108 skins |

| DW Thomas |

Lorinna |

960 lbs |

|

310 skins |

| William McCoy |

Claude Road |

600 lbs |

|

66 skins |

| Charles McCoy |

Claude Road |

40 lbs |

|

|

| Geo [sic] Weindorfer |

Cradle Valley |

31 skins |

|

4 skins |

| Percy Lucas |

Wilmot |

408 skins |

|

56 skins |

| G Coles |

Storekeeper, Wilmot |

|

5 skins |

|

| Jack Linnane |

Wilmot |

|

15 skins |

|

| WM Black |

Black Bluff |

50 skins |

|

3 skins |

| James Perry |

Lower Wilmot |

|

2 skins |

13 skins |

Most of those deprived of skins were bush farmers or farm labourers who hunted as a secondary (primary?) income, while George Coles was probably a middleman between hunter and skin buyer:

Frank Brown (1862–1923). Son of ex-convict Field stockman John Brown, he was one of four brothers who followed in their father’s footsteps (the others were Humphrey Brown c1855–1925, John Thomas [Jacky] Brown, 1857–c1910 and Richard [Dick] Brown). He appears to have been resident stockman at Field brothers’ Gads Hill Station in 1892.[15] Frank and Louisa Brown were resident at JT Field’s Middlesex Station c1905–17. He died when based at Richard Field’s Gads Hill run in 1923, aged 59, while inspecting or setting snares on Bald Hill.[16]

David William Thomas (c1886–1932) of Railton bought an 88-acre farm on the main road at Lorinna from Harry Forward in 1912.[17] His 1914 skins tally suggests that farming was not his main source of income—so the loss must have been devastating. Other Lorinna hunters like Harold Tuson were working in the Wallace River Gorge between the Du Cane Range and the Ossa range of the mountains.

William Ernest (Cloggy) McCoy (1879–1968), brother of Charles Arthur McCoy below, was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Sheffield.[18] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy and the uncle of the well-known snarer Tommy McCoy (1899–1952).[19]

Charles Arthur (Tibbly) McCoy (1870–1962) was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Barrington.[20] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy. Charles McCoy caught a tiger at Middlesex, depositing its skins at the Sheffield Police Office on 30 December 1901.[21] He was the uncle of the later well-known snarer Tommy McCoy.

Gustav Weindorfer (1874–1932), tourism operator at Waldheim, Cradle Valley, during the years 1912 to 1932. By his own accounts during 1914 he shot 30 ‘kangaroos’, eight wombats, six ringtails and one brush possum, as well as taking one ‘kangaroo’ in a necker snare.[22] While the closure of the skins market would have handicapped this struggling businessman, these skins would have been useful domestically, and the wombat and wallaby meat would have gone in the stew.

Percy Theodore Lucas (c1886–1965) was a Wilmot labourer in 1914, which probably means that he worked on a farm.[23] Nothing is known about his hunting activities.

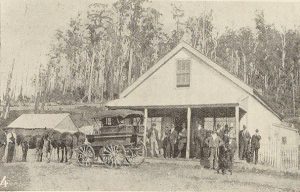

TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store, Percy Lodge photo from the Weekly Courier, 22 April 1905, p.19.

George Coles (1855–1931) was the Wilmot storekeeper whose sons, including George James Coles (1885–1977), started the chain of Coles stores in Collingwood, Victoria.[24] George Coles bought TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store in 1912, operating it until after World War One. In 1921 the store was totally destroyed by fire, although a general store has continued to operate on the same site up to the present.[25] The five skins in George Coles’ possession had probably been traded by a hunter for stores. Coles probably sold them to a visiting skin buyer when the opportunity arose.[26]

John Augustus (Jack) Linnane (1873–1949) was born at Ulverstone but arrived in the Wilmot district in 1893 at the age of nineteen, becoming a farmer there.[27] Like George Francis, Linnane joined the search party for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain in 1905, suggesting that he knew the country well.[28] His abandoned hunting camp near the base of Mount Kate was still visible in 1908.[29] Enough remained to show that Linnane was one of the first to adopt the skin shed chimney for drying skins.[30] He also engaged in rabbit trapping.[31] In 1914 he was listed on the electoral roll as a Wilmot labourer, but exactly where he was hunting at that time is unknown.[32]

Kate Weindorfer, Ronald Smith and WM Black on top of Cradle Mountain, 4 January 1910. Gustav Weindorfer photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Walter Malcolm (WM) Black (1864–1923) was a gold miner and hunter at the Lea River/Black Bluff Gold Mine in the years 1905–15. The son of Victorian grazier Archibald Black, WM Black was a ‘remittance man’, that is, he was paid to stay away from his family under the terms an out-of-court payment of £7124 from his father’s will.[33] He joined the First Remounts (Australian Imperial Force) in October 1915 by falsifying his age in order to qualify.[34] See my earlier blog ‘The rain on the plain falls mainly outside the gauge, or how a black sheep brought meteorology to Middlesex’.[35]

James Perry (1871–1948), brother of a well-known Middlesex area hunter, Tom Perry (1869–1928), who was active in the high country by about 1905. Whether James Perry’s few skins were taken around Wilmot or further afield is unknown.

No tigers at Middlesex/Cradle Mountain?

George Francis survived the financial setback of 1914. Gustav Weindorfer in his diaries alluded to collaboration with him on prospecting and mining activities, but they hunted in different areas. In 1919 Francis co-authored the three-part paper ‘Wild life in Tasmania’ with Weindorfer, which documented their extensive knowledge of native animals, principally gained by hunting them. At the time, the authors claimed, they were the only permanent inhabitants of the Middlesex-Cradle Mountain area, boasting nine years (Weindorfer) and 50 years’ (Francis) residency. They also made the interesting claim that the ‘stupid’ wombat survived as well as it did in this area because it had no natural predators, since the thylacine did not then and probably never had frequented ‘the open bush land of these higher elevations’.[36] While this suggests that George Francis had never encountered a thylacine around Middlesex, it’s hard to believe that his father Jack Francis didn’t, especially given the story that Jack’s early foray into the Vale of Belvoir as a shepherd for William Kimberley was tiger-riddled.[37] It’s also a pity the authors didn’t consult the likes of Middlesex tiger slayers Charlie McCoy (see above) and James Mapps—or rig up a séance with the late George Augustus Robinson and James ‘Philosopher’ Smith.

The dog of GA Robinson, the so-called ‘conciliator’ of the Tasmanian Aborigines, killed a mother thylacine on the Middlesex Plains in 1830.[38] Decades later, ‘Philosopher’ Smith the mineral prospector came to regard Tiger Plain, on the northern edge of the Lea River, as the most tiger-infested place he visited during his expeditions. It was popular among the carnivores, he thought, because the Middlesex stockman’s dogs by driving game in that direction provided a ready food source. ‘I thought it necessary’, he wrote about his experience with tigers,

‘to be on my guard against them by keeping a fire as much as I could and having at hand a weapon with which to defend myself in the event of being attacked by one or more of them … ‘[39]

Smith killed a female tiger on Tiger Plain and took its four pups from her pouch but found they could not digest prospector food (presumably damper, potatoes, bully beef, wallaby or wombat).[40] Philosopher’s son Ron Smith had no reason to doubt his father, as he found a thylacine skull on his property at Cradle Valley in 1913 which is now lodged in Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery.[41] There were still tigers in the Middlesex region at the cusp of the twentieth century. Like ‘Tibbly’ McCoy, James Mapps claimed a government thylacine bounty at this time, probably while working as a tributor at the Glynn Gold Mine at the top of the Five Mile Rise near Middlesex.[42]

George Francis in his will described himself as a ‘shepherd of Middlesex Plains’, yet he met his maker in the Campbell Town Hospital. His parents were dead and he had no remaining relatives. The sole beneficiary of his will was Golconda farmer and road contractor William Thomas Knight (1862–1938), probably an old hunting mate.[43] Francis’s job at Middlesex was filled by the so-called ‘mystery man’ Dave Courtney (see my blog ‘Eskimos and polar bears: Dave Courtney comes in from the cold’), whose life, as it turns out, is an open book compared to that of his elusive predecessor.

[1] Died 11 October 1883, death record no.167/1883, registered at Deloraine, RGD35/1/52 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=maria&qu=francis#, accessed 15 February 2020; inquest dated 13 October 1883, SC195/1/63/8739 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-63-8739, accessed 15 February 2020. A pre-inquest newspaper reporter incorrectly attributed her death to suicide by strychnine poisoning (editorial, Launceston Examiner, 23 October 1883, p.1).

[2] It is likely that Jack Francis and Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley conveyed Maria Francis’s body to Gads Hill Station, where Roden took delivery of it. See ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4; and ‘Supposed case of poisoning at Chudleigh’, Launceston Examiner, 13 October 1883, p.2. Later Roden had the job of removing Stanley’s body for an inquest at Chudleigh (Dan Griffin, ‘Deloraine’, Tasmanian Mail, 13 August 1898, p.26).

[3][3] For the land grant, see Deeds of land grants, Lot 5654RD1/1/069–71In 1890, 1892 and 1894 John and George Francis were both listed as farmers at Mole Creek (Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1890–91, p.200; 1892–93, p.288; 1894–95, p.260). Jack Francis was reported to have left Middlesex in March 1885, being replaced by Jacky Brown (James Rowe to James Norton Smith, 10 March 1885; and to RA Murray, 24 September 1885, VDL22/1/13 [TAHO]). However, he appears to have returned periodically.

[4] She was born to splitter John Wilcox and Rosetta Graves at Longford on 17 July 1841, birth record no.3183/1847 (sic), registered at Longford, RGD32/1/3 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=sarah&qu=wilcox, accessed 14 March 2020; died 25 October 1915 at Launceston (‘Deaths’, Examiner, 8 November 1915, p.1). Mary Ann’s youngest child, Eva Grace Lowe, was born in 1879.

[5] Frank Styant Browne, Voyages in a caravan: the illustrated logs of Frank Styant Browne (ed. Paul AC Richards, Barbara Valentine and Peter Richardson), Launceston Library, Brobok and Friends of the Library, 2002, p.84.

[6] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory for the period 1901–08 listed Jack Francis as an overseer at Gads Hill or Liena, while Mary, as she was described, was listed as a farmer at Liena, meaning Circular Ponds (1901, p.322; 1902, p.341; 1904, p.204; 1906, p.189; 1907, p.192; 1908, p.197).

[7] ‘A veteran drover’.

[8] ‘Return thanks’, Examiner, 2 March 1912, p.1; purchase grant, vol.36, folio 116, application no.3454 RP, 1 July 1912.

[9] Jack Francis bought purchase grant vol.18, folio 113, Lot 5654, on 25 November 1872. He divided it in half, selling the two lots on 6 May 1902 to Arthur Joseph How and Andrew Ambrose How for £30 each.

[10] ‘The mountain mystery: search for Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[11] 1 August 1914, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] See ‘William Aylett: career bushman’ in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.42–43.

[13] See ‘Bert Nichols: hunter and overland track pioneer’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.114.

[14] See ‘Paddy Hartnett: bushman and highland guide’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.93.

[15] On 20 April 1892 (p.179) Frank Brown reported stolen a horse which was kept at Gads Hill, Deloraine Police felony reports, POL126/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Well-known stockrider’s death’, Advocate, 4 June 1923, p.2.

[17] ‘Lorinna’, North West Post, 28 August 1912, p.2; ‘Obituary: Mr DW Thomas, Railton’, Advocate, 21 April 1932, p.2.

[18] Born 21 March 1879, birth record no.2069, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/57 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=william&qu=ernest&qu=mccoy. Accessed 10 April 2020.

[19] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[20] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[21] 30 December 1901, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Gustav Weindorfer diaries, 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TAHO).

[23] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.27.

[24] ‘About people’, Age, 22 December 1931, p.8.

[25] ‘Fire at Sheffield [sic]’, Mercury, 8 November 1921, p.5.

[26] Coles held a tanner’s licence in 1914 (‘Tanners’ licences’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 1 May 1914, p.109), but the legal requirement was that skins had to be sold to a registered skin buyer. Despite this, plenty of people tanned and sold their own skins privately.

[27] ‘”Back to Wilmot” celebration’, Advocate, 12 April 1948, p.2.

[28] 10 July 1905, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[29] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[30] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[31] On 18 April 1910, Linnane reported the theft of 200 rabbit skins from his hut valued at £2, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[32] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.26.

[33] ‘Supreme Court’, Age, 27 February 1885, p.6.

[34] World War One service record, https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1791278/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[35] Nic Haygarth website, http://nichaygarth.com/index.php/tag/walter-malcom-black/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[36] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Victorian Naturalist, vol.36, March 1920, p.158.

[37] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ’In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.2.

[38] George Augustus Robinson, Friendly mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (ed. Brian Plomley), Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1966; 22 August 1830, p.159.

[39] James Smith to James Fenton, 14 November 1890, no.450, NS234/ 2/1/15 (TAHO).

[40] ‘JS (Forth)’ (James Smith), ‘Tasmanian tigers’, Launceston Examiner, 22 November 1862, p.2.

[41] Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 26 September 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO); email from Tammy Gordon, QVMAG, 2019.

[42] Bounty no.242, 30 August 1898, LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO); ‘Court of Mines’, Launceston Examiner, 22 September 1897, p.3; 30 September 1897, p.3.

[43] Will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis, accessed 15 March 2020; ‘Funeral of Mr WF [sic] Knight’, Examiner, 15 April 1938, p.15.

by Nic Haygarth | 11/01/17 | Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

A hunter’s log cabin in the Cuvier Valley (Fred Smithies photo, from the Weekly Courier, 3 July 1929, p.27). From 1927 the Cuvier Valley was part of a game sanctuary. This was not the first time that Smithies, a member of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board, had photographed an illegal hunting hut in the Lake St Clair Reserve.

In 1906 a newspaper contributor calling himself ‘The Rover’ wrote an account of four months’ hunting in a mountain valley near Lake St Clair. The party of four was from Queenstown. They started for the lake through heavy rain in April, each member bearing a pack weighing 23 kg up the Linda Track, precursor of the Lyell Highway—while a mule carried the rest, a mere 141 kg! First stop was the ‘cockatoo hut’, which at the time was a well-known shelter at the Franklin River.[1] Next day, high on Mount Arrowsmith, the grave of John Largan, who had frozen to death there in 1900, served to warn them of the dangers of the highlands.[2] Arriving at Lake St Clair on the second evening after their long tramp, they spent two days exploring the surrounds before settling on a ‘beautiful valley’ 11 km from the lake. Over four days the party built a log hut with a bark roof as their base.

Then, instead of laying down their snare lines, they ‘waited with feverish impatience for the first fall of snow’. Unleash the hounds! ‘The Rover’ knew what many hunters knew: that in heavy snow wallabies were easy prey for dogs:

‘As we had been at the business before, no time was lost in getting to work, two of us going out and two remaining in camp every alternate day … The same remark applies to the dogs, for they soon knock up if the work is not divided between them. The best plan is to take four dogs at a time, for if the kangaroos [Bennett’s wallabies] are plentiful the dogs will kill faster than a man can skin them, it being a common occurrence to have four or five killed within as many minutes. The fastest kangaroo falls a victim to the slowest dog when pursued through three feet of snow’.

The two men back at camp were kept busy pegging out skins, fetching wood for the fire and cooking supper. No mention was made of a skin shed—but the existence of one is implied by the volume of skins obtained and the duration of the expedition. Mouldy or frozen skins were worthless. They needed to be cleaned and kept dry. The skin shed, a unique Tasmanian invention, was developed at about the beginning of the twentieth century. Its inception was one of the reasons for an escalation in the Tasmanian fur industry, enabling longer stints and greater, more valuable hauls in the highlands where possum furs in particular grew thicker.

After one month the mule was revisited at the Clarence River, and divested of its load—which presumably it had not borne in the interim. The snow was then two feet deep, and in June it got deeper, with metre-long icicles draping the eaves of the hut. Now the ‘rough-coated mongrel’ dog showed his superiority to the purebred, with wallabies being slaughtered in all directions.

One day the hunters found the tracks of a ‘hyena, or Tasmanian tiger’. The dogs took up the scent

‘and in a few minutes discovered the enemy. Their angry growls brought us on the scene, when it was plainly to be seen that the tiger intended to fight to the bitter end. With a cry of encouragement to the dogs we urged them on, and immediately they were engaged in mortal combat with their fierce opponent. The struggle was a long one, but at last the combined strength of the four dogs began to tell, and the battle was over. We found on examination that the tiger was one of the largest of its class, measuring 5 ft 6 in [1.69 m] from the end of his nose to the tip of his tail’.

‘The Rover’ claimed a haul of 91 dozen (1092) wallaby skins—and a weight loss of from 15 to 22 kg per man.[3] The mule, not the men, would have borne the skins back to Queenstown. Providing they were in good condition, they would have fetched something in the region of £80–£140 on the fur market, or an average of about £20–£35 per man.[4] While this would have been a very useful income supplement, better money was to be had in an open season on brush possum.

How credible is this anonymous tale? Let’s start with the hunting season. No year is given, but the events described, if they are real, must have taken place in the period 1901–05. Which season is it likely to be? Throughout the period 1901–05 the season for wallaby was four months, 1 April to 31 July, with closed season for possums in 1903 and 1904 and a one-month season (July) in 1901, 1902 and 1905.[5] So wallabies would have been the focus for many hunters during these seasons, and almost without exception in 1903 and 1904. As for the very heavy snow falls, there was plenty of snow at Cradle Mountain in July 1905 when hunter Bert Hanson disappeared in a blizzard. Hanson and his mate Tom Jones were also using dogs to hunt down wallabies.[6]

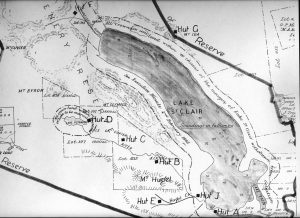

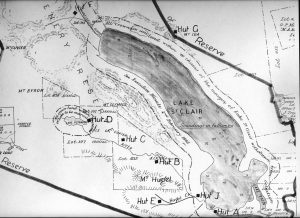

A map showing Cuvier Valley hunting huts visited during a police raid on the Lake St Clair Game Sanctuary in 1927. From AA580/1/1 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

What was the ‘beautiful valley about 10 miles long by two in width, and bounded on each side by high ranges extending as far as the eye could reach, rising almost perpendicularly from the valley below’? Allowing for a little poetic licence, it could be the Cuvier Valley west of Mount Olympus, where hunters like Bert and Dick Nichols operated two decades later.[7]

What about the thylacine: was the carcass submitted for a government thylacine bounty? Plenty of applications were made for the bounty in the spring of the years 1901–05, but without knowing the origin of each application it is very difficult to track down ‘The Rover’ or his mates from Queenstown.[8] Given the value of the wallaby skins they obtained, carting a single thylacine carcass back to Queenstown in order to submit it for a £1 bounty may not have been a priority for them anyway.

In short, the story is plausible. I hope there are further missives from ‘The Rover’, giving more insight into the task of feeding the world’s craving for furs.

[1] See, for example, JW Beattie, ‘Out west with salmon fry’, Mercury, 18 February 1903, p.6; ‘Alluvial gold’, Mercury, 25 August 1935, p.8.

[2] See ‘Mount Arrowsmith tragedy’, Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette, 3 September 1900, p.2.

[3] ‘The Rover’, ‘A Tasmanian winter camp’, Weekly Courier, 26 May 1906, p.37.

[4] In August 1901 ‘kangaroo’ skins free from shot were fetching £0-1-6 to £0-1-8 each (‘Commercial’, Mercury, 17 August 1901, p.2); in August 1905 ‘kangaroo’ fetched from £0-1-11 to £0-2-6 (‘Commercial’, Examiner, 12 August 1905, p.4). My calculations assume that all the skins obtained were Bennett’s wallabies, when it is likely that some were pademelons. ‘The Rover’ does not specify.

[5] Editorial, Daily Telegraph, 30 July 1901, p.2; ‘To correspondents’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 July 1902, p.2; ‘Current topics’, Examiner, 31 March 1903, p.4; ‘Warning to possum poachers’, Examiner, 19 June 1903, p.6; ‘To correspondents’, Examiner, 13 April 1904, p.4; ‘Kangaroos and opossums’, Daily Telegraph, 3 May 1905, p.2.

[6] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘The mountain mystery’, Daily Telegraph, 5 August 1905, p.6.

[7] See Gerald Propsting to the Secretary for Public Works, 4 August 1927, file AA580/1/1(Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [afterwards TAHO]); ‘Lake St Clair Reserve: allegations of poaching’, Mercury, 26 May 1927, p.10.

[8] Government thylacine bounty payments in the years 1888—1909 are recorded in LSD247/1/2 and LSD247/1/3 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 29/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

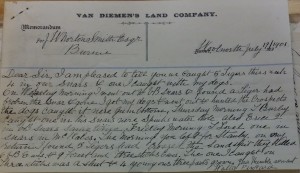

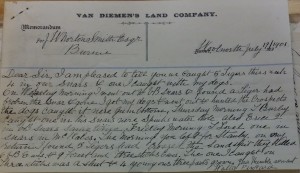

Tigers to the left, tigers to the right … VDL Co stockman Walter Pinkard reports from the thick of the Woolnorth tiger action 8 June 1901. From VDL22-1-32 (TAHO).

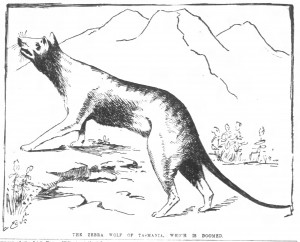

How do you stigmatise an animal? Try branding. The change from ‘hyena’ to ‘tiger’, as the common descriptor for the thylacine, was a major step in its reinvention as a sheep killer. Both ‘tiger’ and ‘hyena’ were used commonly to describe the thylacine during much of the nineteenth century, with ‘tiger’ only becoming the dominant term late in that century and into the twentieth century. For example, the records of the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) show that the company’s local officers used ‘hyena’ almost universally to describe the thylacine during the company’s first period of farming its Woolnorth property, in the years 1827–51—whereas later they went exclusively with ‘tiger’.

The stripes on the thylacine’s back presumably prompted the original attributions of the names ‘tiger’ and ‘hyena’, by Robert Knopwood and CH Jeffreys respectively.[1] The Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) and the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) were mentioned regularly in nineteenth-century newspaper items about life in the British Raj, which some foreign-born Tasmanians had also visited. Tigers, leopards, cheetahs, wolves and, less often, hyenas, preyed on stock and sometimes people in India. Government rewards were offered there for killing tigers. While the fearsome tiger was the favourite ‘sport’ of Indian big game hunters, the hyena, unlike its some-time Tasmanian namesake, was not the primary carnivore in the Bengali ecology. It was sometimes reported to be ‘cowardly’, ‘skulking’ and lacking in the fight desired by the game hunter.[2]

Likewise, the thylacine was also often described as ‘cowardly’ in its alleged sheep predations.[3] By the 1870s and 1880s, however, when the profitability of the wool industry was declining, those employed in the industry seem to have used the term ‘tiger’ almost universally to describe the thylacine. Perhaps shepherds preferred ‘tiger’ because it glamorised their profession, introducing an element of danger and likening them to the big game hunters of India. The way in which some thylacine killers made trophies of their kills and were photographed with these suggests identification with big game hunting.[4] By the same token, dubbing the thylacine a ‘tiger’ provided a potential scapegoat for sheep losses, enabling the shepherd to shift the blame for his own poor performance on to what may henceforth be perceived as a dangerous predator. Wool-growers wanting to eliminate the thylacine would also be keen to cast it as a dangerous predator. John Lyne, the east coast wool-grower who led the campaign for a government thylacine bounty, referred to the animal as a ‘tiger’ but also as a ‘dingo’, thereby equating the thylacine with the well-known mainland Australian sheep predator.[5] In 1887 ‘Tiger Lyne’s campaign was mocked to the effect that

‘the jungles of India do not furnish anything like the terrors that our own east coast does in the matter of wild beasts of the most ferocious kind. According to ‘Tiger Lyne’, these dreadful animals [thylacines] may be seen in their hundreds stealthily sneaking along, seeking whom they may devour …’[6]

The VDL Co correspondence records show that the company’s local agent James Norton Smith also originally described the thylacine as a ‘hyena’. He appears to have adopted ‘tiger’ as a descriptor in 1872 after his Woolnorth overseer, Cole, used the term in a letter to him. James Wilson, Woolnorth overseer 1874–98, also used the term ‘tiger’ exclusively, and after 1876 Norton Smith followed suit. The term ‘hyena’ was not used in any correspondence written or compiled by VDL Co staff, in Woolnorth farm journal records or Woolnorth accounting records in the years 1877–99. While Norton Smith occasionally used the term ‘hyena’ in the years following Wilson’s retirement from Woolnorth, ‘tiger’ remained his preferred term and this continued to be used exclusively at Woolnorth.

Theophilus Jones: thylacine prosecutor

As Robert Paddle and others have suggested, pastoralists generally blamed the thylacine as well as the rabbit for their declining political power and wealth.[7] One of the greatest prosecutors of the thylacine at this time was Theophilus Jones. In 1877–78 and 1883–85 two young British journalists toured Tasmania writing serialised newspaper accounts of its districts. Since both were newcomers, with limited knowledge of the colony, they could be expected to repeat unquestioningly much of what they were told. The first of these writers, E Richall Richardson, travelled all the populated regions of Tasmania except the far north-west and Woolnorth. On the east coast, Richardson interviewed woolgrowers, including John Lyne, the MHA for Glamorgan who a decade later would petition to establish the thylacine bounty. Richardson’s only comment upon the thylacine as a sheep killer or any kind of nuisance in his 92-part series was not on the east coast or in the Midlands, but in reference to the twice-yearly visits of graziers to their Central Plateau stock runs:

‘If when the master comes up, and there is a deficit in the flock, the rule is ‘blame the tiger’. The native tiger is a kind of scape-goat amongst shepherds in Tasmania, as the dingo is with shepherds in Queensland; or as ‘the cat’ is with housemaids and careless servants all over the world. ‘It was the cat, ma’am, as broke the sugar-basin’; and ‘It was the tigers, sir, who ate the sheep’.[8]

Theophilus Jones, in his 99-part series written in the years 1883–85, told a different tale. By this time, only half a decade since Richardson wrote, the wool industry had declined markedly. The first ‘stock protection’ association, that is, a locally subscribed thylacine bounty scheme, was formed at Buckland on the east coast in August 1884 while Jones was touring the area.[9]

Jones’ circumstances were different to the earlier writer’s. Although travelling in poverty, Richardson was a single man with no commitments. Jones, on the other hand, was trying desperately to support a wife and large family. While travelling Tasmania as a newspaper correspondent, he doubled as an Australian Mutual Provident (AMP) assurance salesman. Much more than Richardson, Jones concentrated on populated areas where he might sell assurance and find well-to-do patrons. He not only visited Woolnorth but practically every large grazier in the colony, and he flattered men who were in a position to financially benefit him. Whether currying favour or being merely ignorant of the truth, it is not then surprising to find Jones spouting woolgrowers’ vituperative against the thylacine. Henry, John and William Lyne appear to have fed Jones a litany of almost six decades of warfare with Aborigines and the wildlife, as if these were age-old predators: ‘Blacks and tigers made the life of a young shepherd one of continued mental strain’.[10] For Jones the tiger was generally the biggest killer of sheep, followed by the devil and the ‘eaglehawk’. The thylacine had ‘massive’ jaws, ‘serrated’ teeth and a powerful body like that of a kangaroo dog.[11] It was ‘a great coward’, savaging lambs but refusing battle with man or dog.[12] Jones applauded the stock protection association, hoping that it would reduce eagles and tigers ‘to the last specimen’.[13] That is, drive them to extinction.

Jones had already visited Woolnorth. He found that, like his predecessors, tigerman Charlie Williams kept ‘trophies’ at Mount Cameron, his prize being a thylacine skin 2.3 metres long.[14]

Like Williams, the government was actually more interested in possums. It had cited increased hunting, in response to high skin prices, as a reason to introduce the Game Protection Amendment Act (1884), which protected all kinds of possum during the summer, allowing open season from April to July inclusive. During debate about the bill in the House of Assembly, James Dooley ‘likened the sympathy for the native animals to that which was excited in favour of the native race’, to which MHA for Sorell, James Gray, responded that ‘the only resemblance between the natives and the opossums were that they were both black. (Laughter.)’[15]

It was also Gray who in 1885 asserted the ‘necessity of something being done to stop the ravages of the native tiger in the pastoral districts of the colony …’.[16] John Lyne took up this stock protection measure: a £1 per head thylacine bounty operated from 1888 to 1909. About 2200 bounties were paid across Tasmania, helping to drive the animal towards extinction. Bounties were paid by the Colonial Treasurer upon thylacine carcasses being presented to local police magistrates or wardens.

Woolnorth was a remote settlement with challenges faced by few wool-growing properties. Distance from towns, doctors and schools was probably one reason that it was so difficult to find and keep a reliable man to work at Mount Cameron West in particular. Time and time again James Wilson’s farm journals record the Mount Cameron West shepherd’s monthly visits to the main farm at Woolnorth to get supplies and return with them to his own hut: ‘Tigerman came down’ and ‘Tiger went home’. ‘Tigerman’, which carries the implication of being a dedicated thylacine killer, may have been coined to glamorise the position in order to attract staff. It and the general use of the term ‘tiger’ at Woolnorth may also indicate that the overseer, his stockman and farm hands wanted to shift the blame for sheep losses on the property.

Table 3: Occurrences of various names for the thylacine in Tasmanian newspapers for the years 1816–1954 (in both text and advertising), taken from the Trove digital newspaper database 22 December 2016

| NAME |

1816–87 |

1888–1909 |

1910–54 |

TOTAL |

| Tasmanian tiger |

141 (84–57) |

96 (64–32) |

434 (420–14) |

671 (568–103) |

| Native tiger |

326 (199–127) |

197 (186–11) |

88 (88–0) |

611 (473–138) |

| Tasmanian native tiger |

5 (5–0) |

0 (0–0) |

7 (7–0) |

12 (12–0) |

| Thylacine/thylacinus |

43 (43–0) |

20 (20–0) |

93 (91–2) |

156 (154–2) |

| Hyena/native hyena/opossum hyena |

165 (107–58) |

46 (39–7) |

84 (77–7) |

295 (223–72) |

| Dog-faced opossum |

1 (1–0) |

0 (0–0) |

0 (0–0) |

1 (1–0) |

| Tasmanian wolf |

9 (3–6) |

11 (11–0) |

97 (97–0) |

117 (111–6) |

| Marsupial wolf |

4 (4–0) |

6 (6–0) |

74 (74–0) |

84 (84–0) |

| Tiger wolf |

7 (7–0) |

3 (3–0) |

3 (3–0) |

13 (13–0) |

| Native wolf/native wolf-dog |

5 (5–0) |

0 (0–0) |

5 (5–0) |

10 (10–0) |

| Zebra wolf |

5 (5–0) |

6 (6–0) |

2 (2–0) |

13 (13–0) |

| Tasmanian tiger wolf |

1 (1–0) |

0 (0–0) |

0 (0–0) |

1 (1–0)[17] |

In her book Paper tiger: how pictures shaped the thylacine, Carol Freeman stated that ‘Tasmanian wolf’ and ‘marsupial wolf’ were the principal names given to the thylacine in the zoological world until well into the twentieth century, described how in the period from the 1870s to the 1890s ‘wolf-like’ visual images of the species predominated in natural history literature, and speculated that illustrations of this kind, repeated in mass-produced Australian newspapers in 1884, 1885 and 1899, ‘influenced perceptions close to the habitat of the thylacine and encouraged government extermination policies’.[18]

The National Library of Australia’s Trove digital newspaper database allows us to test the idea that the depiction of the thylacine as a ‘wolf’ or as ‘wolf-like’ had any traction in Tasmania. Unlike the inter-colonial illustrated newspapers to which Freeman referred—Australian Graphic (1884), Illustrated Australian News (1885) and Town and Country Journal (1899)—the Trove search represented by Table 3 is restricted to 88 Tasmanian newspaper titles, 23 of which published during at least part of the period of the Tasmanian government thylacine bounty 1888–1909. More than any other type of publication, the Tasmanian newspapers are likely to contain the language of ordinary Tasmanians, expressed either by journalists, newspaper correspondents or by themselves in letters to the editor—and they were more likely than any other form of publication to be read by and contributed to by graziers, legislators and hunter-stockmen involved in killing thylacines. Some of these newspapers carried occasional lithographed or engraved images, but the search does not include the two best-known Tasmanian illustrated newspapers, the Weekly Courier (1901–35) and the Tasmanian Mail/Illustrated Tasmanian Mail (1877–1935), which (in December 2016) were yet to be digitised for the Trove database. Trove coverage of Tasmanian newspapers begins with the Hobart Town Gazette and Southern Reporter in 1816 and goes no later than 1954 except in a few cases.

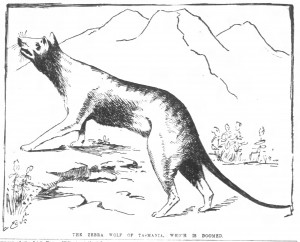

The Tasmanian ‘zebra wolf’, from the San Francisco Chronicle, 18 February 1896, p.6.

The Trove search suggests that in the period 1888–1909 the terms ‘native tiger’ (197 hits) and ‘Tasmanian tiger’ (96 hits) were much more widely used by the general public in Tasmania that any permutation of ‘wolf’ (26 hits altogether), and that ‘hyena’ (46 hits) was also more popular than ‘wolf’. While the 1884 issue of Australian Graphic which contained the illustration of the ‘Tasmanian zebra wolf’ is not included in the Trove search, it did pick up a description of that issue of the newspaper by the editor of the Mercury. Clearly he was not profoundly influenced by the engraving of the thylacine:

‘The illustrations are fairly good, excepting those which are apparently intended to be amusing; these amuse only by their extreme absurdity. There is a cut representing, what is termed, a Tasmanian zebra wolf. It is about as true to nature as the pictures exhibited outside a travelling menagerie’.[19]

The ‘Tasmanian wolf’ as a sheep devourer in 1947, when the term ‘wolf’ had gained some popular usage: from Hotch Potch (the magazine of the Electrolytic Zinc Company of Australasia), October 1947, vol.4, p.2 (TAHO).

The names ‘Tasmanian wolf’ (97 hits) and ‘marsupial wolf’ (74 hits) only gained traction in Tasmanian newspapers in the period (1910–54) when the thylacine was clearly disappearing or virtually extinct, that is, when the scientific and zoological community entered the popular press in its desperate search for a remnant thylacine population. This is also the period in which the Latin scientific name for the animal, thylacine, thylacinus (93 hits) occurred much more frequently in the Tasmanian press. However, even in this period, ‘tiger’ (529 hits) remained easily the predominant descriptor for the thylacine. The fact that the thylacine received more attention in the press during the years when it could not be found than when it could speaks for itself, although of course many more newspapers were published in the first half of the twentieth century than in the nineteenth.

[1] Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian tiger: a lesson to be learnt, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, 1998, p.15.

[2] ‘Pigsticking in India’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1897, p.3; ‘Shikalee’, ‘Wild sport in India’, Launceston Examiner, 24 July 1897, p.2.

[3] See, for example’, ‘Royal Society of Tasmania’, Courier, 16 June 1858, p.2; or ‘Town talk and table chat’, Cornwall Chronicle, 27 March 1867, p.4.

[4] See, for example, [Theophilus Jones], ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[5] See, for example, ‘Parliament’, Launceston Examiner, 1 October 1886, p.3.

[6] Tasmanian Mail, 3 September 1887; cited by Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000, p.161.

[7] See Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger.

[8] E Richall Richardson, ‘Tour through Tasmania: no.89: cattle branding’, Tasmanian Tribune, 14 March 1878, p.3.

[9] ‘Buckland’, Mercury, 15 August 1884, p.3.

[10] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.61’, Mercury, 8 November 1884, supplement, p.1.

[11] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.49’, Mercury, 26 July 1884, p.2.

[12] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[13] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.56’, Mercury, 20 September 1884, p.2.

[14] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[15] ‘House of Assembly’, Mercury, 24 October 1884, p.3.

[16] ‘Meeting at Buckland’, Mercury, 14 August 1884, p.2; ‘The native tiger’, Mercury, 25 September 1885, p.2.

[17] This list was compiled on 22 December 2016. The numbers in brackets indicate how many of the hits occurred in text and how many in advertising. While occurrences of a name in advertising are a relevant gauge of its public usage, it is recognised that numbers of hits are exaggerated by repeated publication of the same advertisement. Another issue noted in this search of Trove was the need to weed out references to ‘native and tiger cats’, which refer to the two species of quoll rather than to the thylacine. There are also cases of repetition in the sense that some textual references involve two or more names for the thylacine, such as ‘the Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf’. In such cases both names have been included in the table.

[18] Carol Freeman, Paper tiger: how pictures shaped the thylacine, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.117and 140.

[19] Editorial, Mercury, 28 March 1884, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 28/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

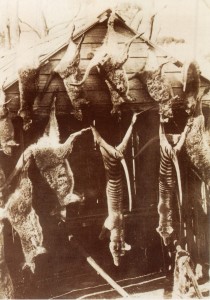

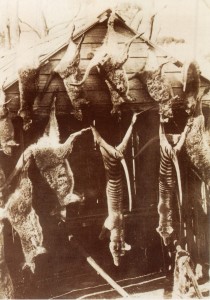

A photo of two thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) carcasses suspended from a hut in Waratah, Tasmania, has intrigued students of the animal’s demise. Who killed these tigers? Eric Guiler speculated that they might have been taken by a Waratah hunter John Cooney who collected two government thylacine bounties in 1901.[1]

In fact the photographer, Arthur Ernest Warde, was himself a hunter and future Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, and the photo probably depicts his own kills. The man in question was a wheeler and dealer who spent three decades in Tasmania, turning his hand to any useful practical skill—including photography and exploiting the fur trade. The terms of Warde’s stint at the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s (VDL Co’s) Woolnorth property in the years 1903–05 confirm that, far from being specialist thylacine killers, the so-called Woolnorth tigermen were simply regular hunter-stockmen who also took responsibility for managing snares set for thylacines at Green Point near latter-day Marrawah. Given this collision of photographer and tiger snarer, it is tantalising to wonder what tiger-related photos Warde took while working at Woolnorth that may still remain undiscovered in a family scrapbook, or which may have long since mouldered away in someone’s back shed, lost for all time.

Ernest Warde photo of Maori chiefs, 1998:P:0383, QVMAG

Warde’s early life remains as mysterious as his tiger photo. In Wellington, New Zealand in 1890 he married renowned whistler and music teacher Catherine Elizabeth Walker, née Dooley, the daughter of Zeehan shopkeeper Joseph Benjamin Dooley and his wife Annie Dooley.[2] The Wardes, both of whom were known by their middle name, appear to have been in Bendigo in 1891 and by 1893 had relocated to Inveresk, Launceston, where the photographer, ‘late of New Zealand’, presented images of Maori chiefs to the Queen Victoria Museum.[3] The couple’s first child, Winifred Warde, was born at Launceston in 1893.[4]

The Warde photo of the two thylacine carcasses, from Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian tiger: a lesson to be learnt, p.129.

In 1896 the Wardes were in Devonport, in 1897 in Waratah, where second daughter Mabel was born.[5] Elizabeth taught music in both towns.[6] It was supposedly at Waratah that Warde took the intriguing photo, which shows two thylacine and eight wallaby carcasses hanging from the front of a building more closely resembling a woodshed than a hunting hut. The photo slightly pre-dates the era of the skinshed, the unique Tasmanian invention which revolutionised high country hunting by enabling hunters to dry large numbers of skins without leaving the high country. In fact, the photo does not show drying skins, but carcasses which are yet to be skinned. What is the purpose of the image? It is not the conventional trophy photo, which would pose the hunter with his trophy kill. Warde himself collected two thylacine bounties, ten months apart, in September 1900 and July 1901, while living at Waratah, where he probably learned to hunt.[7] Just as the bushman Thomas Bather Moore celebrated in verse the incident in which one of his dogs killed a ‘striped gentleman’, perhaps for Ernest Warde the novelty of killing a thylacine or two justified commemoration or memorialisation of the event with a photo. It is likely that he killed at least one of the thylacines in the photo, and afterwards submitted it for the government bounty.

Warde’s Osborne Studio photo of the fire at ER Evans boot shop and house, Burnie.

From the Weekly Courier, 1 March 1902, p.17.

Warde’s Osborne Studio photo of EJ Wilson’s children, 1986:P:0045, QVMAG.

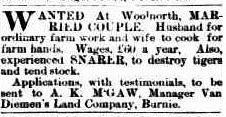

Warde was one of many to have practised photography in Waratah, and with the town’s population still growing, he would not be the last. However, in December 1901 a better photographic opportunity arose in a coastal centre, Burnie, when John Bishop Osborne decided to move on. Warde took over Osborne’s Burnie studio, while also operating a farm at Boat Harbour and advertising his and Elizabeth’s services as musicians.[8] In 1902, while Elizabeth was busy producing the couple’s third child, Francis Harold Warde, photos credited to Warde and to Warde’s Osborne Studio photos appeared in the Weekly Courier and Tasmanian Mail newspapers.[9]

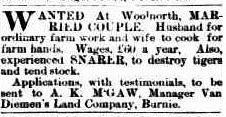

The tigerman job advertised, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 22 May 1903, p.3.

Warde appears to have made the acquaintance of VDL Co agent AK McGaw while supplying photos to the company. The photography business must not have been lucrative, as in May 1903 he agreed to replace the gaoled George Wainwright as the Mount Cameron West tigerman.[10] Warde’s contract as ‘Snarer’ shows him to be a general stockman and farm hand engaged for the Mount Cameron West run, with the killing of ‘vermin’ (that is, all marsupials) his primary duty:

‘It is hereby agreed that the Snarer shall proceed to Mount Cameron Woolnorth … and shall devote his time to the destruction of Tasmanian Tigers, Devils and other vermin and in addition thereto shall tend stock depasturing on the Mount Cameron Studland Bay, and Swan Bay runs, also effect any necessary repairs to fences and shall immediately report any serious damage to fences or any mixing of stock to the Overseer & shall assist to muster stock on any of the above runs whenever required to do so & generally to protect the Company’s interests shall also prepare meals for stockmen when engaged on the Mount Cameron Run’.

The pay was £20 plus rations (meat, flour, potatoes, sugar, tea, salt, with a cow given him for milk) with the snarer providing his own horse.[11] A butter churn was later provided, and farm manager James Norton Smith added that ‘when he wants a change he can catch plenty of crayfish’.[12] No rent was paid for the Mount Cameron West Hut, and the former company reward of £1 per thylacine still applied. In addition, the VDL Co agreed to supply the snarer ‘with hemp and copper wire for the manufacture of tiger snares only (the Snarer supplying such materials as he may require for Kangaroo or Wallaby snares)’.[13] That is, the necker snares used to catch thylacines were stronger than those used to catch wallabies and pademelons. It was the same deal as for his predecessors: the company supplied a small wage and rations, encouraging the stockman-hunter to protect his flock by killing thylacines and keep the grass down by killing other marsupials. In July 1904 Warde advertised in the newspaper for an ‘opossum dog’, which he was willing to exchange for a ‘splendid kangaroo dog’. He knew that the best money was in brush possum furs.[14]

Warde was the last stockman-hunter based at Mount Cameron West. Nearing the close of 1904 he was also trying to ‘get a good line of snares down from the Welcome [?] forest into the back of the Studland bay knolls’, which would give him ‘a splendid tiger break …’[15] However, he had probably already landed the last of his twelve thylacines for the company. In February 1905 the Mount Cameron West Hut was burnt down, Warde’s family escaping the flames late at night in the breadwinner’s absence.[16] That the hut was not replaced for years confirms that the thylacine problem, real or perceived, had abated.[17]

After leaving Mount Cameron West, Ward ditched the ‘e’ from the end of his surname and complemented the Boat Harbour farm with a general store. The Wardes remained there until in 1923 they sold up their store to Hamilton Brothers of Myalla and relocated to New Zealand, where A Ernest Warde reattached his ‘e’ and reinvented himself firstly as an Otago real estate agent, working for his father-in-law, then as an Auckland used car salesman.[18] Elizabeth Warde disappeared from the picture and, appropriately, Ernest wound back his personal odometer to 49 years when in 1932 he took his new 33-year-old bride Mary Winifred Tremewan to see England and America.[19] The new marriage ended when the couple was living in Sydney in the mid-1940s.[20] Warde’s death certificate, in July 1954, described him as an ‘investor’. In truth, he was a trans-Tasman jack-of-all-trades who happened to be the last of the Woolnorth tigermen.[21]

[1] Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian Tiger: a lesson to be learnt, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, 1998, p.129. Cooney’s bounty payment was no.249, 19 June 1901 (2 adults, ’11 June’), LSD247/1/ 2 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [hereafter TAHO]).

[2] For her prowess as a whistler, see ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 15 January 1894, p.5; ‘Burston Relief Concert’, Daily Telegraph, 16 January 1894, p.3 and ‘Entertainment at the Don’, North West Post, 21 April 1894, p.4. Elizabeth Walker is the mother’s name given on the couple’s three children’s birth certificates. On the 1903 Electoral Roll her name is given as Catherine Elizabeth Warde.

[3] ‘Australian Juvenile Industrial Exhibition’, Ballarat Star, 26 May 1891, p.4; ‘The Museum’, Launceston Examiner, 23 December 1893, p.3.

[4] She was born 31 August 1893, birth registration no.606/1893, Launceston.

[5] In 1896 E Warde of West Devonport advertised to sell a camera, lens and portrait stand (advert, Mercury, 23 May 1896, p.4). In 1897 the Wardes featured in a Waratah dance (‘Plain and Fancy Dress Dance’, Launceston Examiner, 9 October 1897, p.9). Mabel Warde’s birth was registered as no. 2760/1898, Waratah.

[6] Advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 January 1902, p.3.

[7]; Bounties no.293, 18 September 1900 (’11 September’); and no.305, 12 July 1901, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[8] See advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 December 1901, p.4; ‘Table Cape’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 19 November 1901, p.2. John Bishop Osborne, the former Hobart photographer, had been on the move every few years since setting up at Zeehan in 1890. Osborne moved to Penguin, and he would end his days in Longford, where he lived 1921–34. Ernest and Elizabeth Warde advertised that they were available to supply music to parties and balls, while Elizabeth also sought piano, organ and dance students (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 January 1902, p.3).

[9] Francis Harold Warde was born at Alexander Street, Burnie, on 17 December 1902 (registration no. 2061/1903). Catherine Elizabeth Warde and Ernest Warde were listed at Burnie on the 1903 Electoral Roll.

[10] The new operator of the Osborne Studio was Mr Touzeau of Melba Studio, Melbourne (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 27 June 1903, p.1). Warde held a furniture sale at his Alexander Street, Burnie, residence in June 1903 (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 13 June 1903, p.3) and advertised for a ‘strong quiet buggy Horse and good double-seated Buggy (tray-seated preferred …’ (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 8 June 1903, p.3).

[11] For Warde’s proposed rations, see James Norton Smith to AK McGaw, 4 June 1903, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[12] James Norton Smith to AK McGaw, 4 June 1903; Ernest Warde to AK McGaw, 7 October 1903, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[13] Agreement between the VDL Co and Ernest Warde, 29 May 1903, VDL20/1/1 (TAHO).

[14] Advert, North West Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 26 July 1904, p.3.

[15] E Warde to AK McGaw, 22 December 1904, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Marrawah’, North West Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 February 1905, p.2.

[17] Woolnorth farm journal, 3 February 1905, VDL277/1/32 (TAHO).

[18] ‘Boat Harbor’, Advocate, 31 January 1923, p.4; ‘Bankruptcy’, Auckland Star, 27 September 1929, p.9.

[19] Did Elizabeth Warde die or did the couple divorce? No record of her was found. According to their marriage certificate (registration no.8401/1929), Mary Winifred Tremewan was born in New Zealand in October 1898. For their ten-month English and American holiday, see ‘The social round’, Auckland Star, 6 January 1933, p.9 and UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960. They sailed from Sydney to London on the Ormonde.

[20] Record no.1208/1944, Western Sydney Records Centre, Kingswood, NSW.

[21] Warde was not the last man to kill thylacines at Woolnorth, but the last in a long line of hunter-stockmen appointed specifically to Mount Cameron West to look after stock and manage the thylacine snares at Green Point.