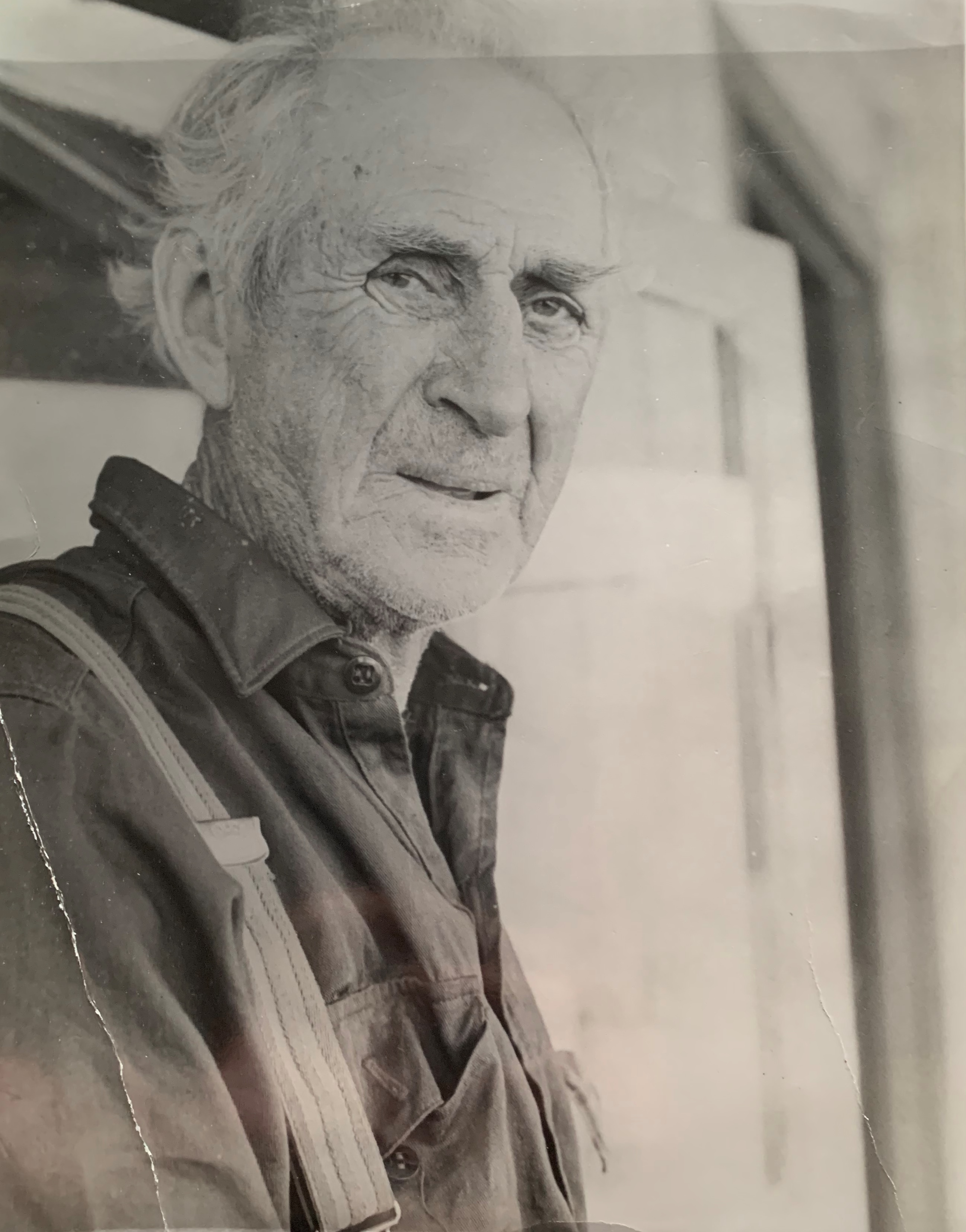

One of north-eastern Tasmania’s greatest hunters was Joseph Clifford (1856–1932), a bush farmer at The Marshes, on Ansons River.[1] Clifford was an incidental snarer of tigers who cottoned onto the live tiger trade as they grew scarcer and more valuable. He was born to ex-convict farmer John Clifford (c1822–1919) and bounty immigrant Mary Ann Lock (aka Anne Viney, c1828–94) at Georges Bay (St Helens).[2] In 1879, as an illiterate 23-year-old farmer, Joseph married 20-year-old farmer’s daughter Emma Summers (c1859–1937).[3] Their four sons and two daughters grew up at The Marshes, where the marshland stretched along both sides of the Anson River and the herbage was plentiful for the stock.[4]

Tigers were also relatively plentiful. In August 1889 a ‘case of native tigers’ was shipped out of Boobyalla to Launceston on the coastal trader Dorset.[5] It was a mother and three cubs destined for William McGowan, manager of the zoo in Launceston’s City Park, who received 21 live thylacines, mostly from the north-east, between June 1885 and July 1893.[6] Perhaps some of them came from Grodens Marsh, across the river from the house at The Marshes. Here Joseph Clifford claimed to have seen a tiger sneak amongst the sheep in order to kill a lamb. He believed that tigers struck the sheep at dusk or dawn, particularly in foggy conditions, taking motherless lambs and any weak ewes. He claimed to have seen as many as nine tigers at one time and developed the belief that they hunted in packs. When the working dogs dragged their chains into their kennels with fear, Joseph released the so-called staghounds, hunting dogs, to tackle the interlopers.[7] These dogs were a mix of great Dane and greyhound, and while used chiefly in possuming they had no fear of tigers.[8]

On one occasion, at a place called the Thomas, Joseph came across five tigers chasing a bandicoot. Most of his staghounds pursued the group, but one dog went after a tiger that broke away on its own. His third son Harry Clifford (c1891–1974) recalled that:

‘When he [Joseph] got down to where the other two [the lone dog and the lone tiger] was they was [sic] both standing up on their hind legs like two dogs fighting’.[9]

Harry and Emma, his mother, were both scared of tigers. Harry recalled his mother telling him that she saw tigers killing their sheep. One time as Joseph arrived home from a hunting trip, Emma said, ‘Oh the tigers have been here again after the sheep.’ ‘Why didn’t you let the dogs loose?’, Joseph replied. ‘Of course’, said Harry, looking back, ‘she was too scared to go out’. On another occasion when the dogs were let loose they ran down a tiger at Dead Horse Creek, east of the homestead. Harry recalled that ‘the next day the others [other tigers] set up in the little paddock down there howling like dogs’, as if lamenting a missing family member.[10]

Joseph claimed government bounties for perhaps 27 adult and 2 juvenile thylacines (worth £28) in the period 1892–1903, including at least 5 adults in 1897.[11] These would have been incidental killings in the course of landing thousands of kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons and brush and ringtail possums. Snaring was essential to the survival of many poor bush families, and the temptation to snare illegally out of season, tanning skins to sell locally, was strong. In 1905 Joseph suffered a serious setback when a zealous constable found a stash of 337 possum skins and some kangaroo skins concealed under a hay stack at The Marshes out of season, for which he was fined a very hefty £59 17 shillings.[12] He would have needed a very good legal hunting season to make up for it.

The switch to the live tiger trade

While the demand for live tigers was low, there was insufficient inducement for some hunters to undertake the considerable trouble involved in keeping them alive and getting them to market. Sarah Mitchell of Lisdillon near Swansea, for example, was offered £6 for a live tiger by the Sydney Zoological Society in 1890 but ended up £5 out of pocket when it died in transit.[13]

The price of a live tiger had probably increased by 1901, when Joseph Clifford brought a thylacine threesome home on the back of a horse, apparently having snared the mother without killing her.[14] He kept the mother and two pups in a barn at The Marshes, with the idea of selling them, but he couldn’t get them to eat. He caught live native hens and wallabies to feed them but the captives took no interest. Finally the thylacine family starved to death, leaving Joseph to claim £2 for presentation of their carcasses under the government bounty scheme and whatever additional money he could get for the skins themselves.[15]

This incident brought about a change in thinking. Joseph originally used necker snares, with the intention of killing his prey, but now he switched over to footer or treadle snares in order to spare tiger lives and collect a bigger prize.[16] Reasoning that thylacines might survive longer in something resembling their natural habitat, he built an enclosure for them on a marsh at nearby Wurrawa. It was a chicken-wire pen about six metres long by two wide, with tall timber posts.[17] It was here that Harry Clifford remembered his father teaching him, as a teenager, to immobilise a tiger by grabbing its tail from behind and lifting its hind quarters off the ground.[18] How many live tigers the Cliffords caught in the early 1900s and who they sold them to is unknown. The most likely recipient is William McGowan of Launceston’s City Park Zoo, who received six tigers June 1898–June 1901 (three of those are known to have come from the Great Western Tiers), and another 24 June 1901–February 1906.[19] Mary Grant Roberts of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point in Hobart also started buying tigers in 1909, followed by James Harrison of Wynyard in 1910, but as mentioned previously there were also mainland buyers.

Harry Clifford’s tiger experiences

Harry Clifford saw at least fifteen tigers during the first half of his life, without even going out of his way.[20] ‘We didn’t go shooting tigers’, he asserted. ‘They came to us’, that is, they entered the Clifford property and ended up in Clifford snares mostly set for other animals. However, Harry did set two tiger traps at The Marshes, both like heavy duty rabbit traps. He placed one on a crossing log on the Anson River, a typical setting for a snarer, but it seems he never landed his intended prey.

On one occasion while snaring Harry Clifford met a female tiger on a track. He had just slung a wallaby over his shoulder which he had taken out of a snare. As he advanced towards the next snare his dogs grew excited and began to retreat behind him, betraying what lay ahead. Harry was not the first person to assert that a tiger on a track would not move out of the way of a human.[21] The female sat steadfastly on the track ahead of him. Guessing that the object of her interest was the large slab of fresh meat on his shoulder, he slowly lowered it to the ground in front of him and backed off. As the tiger grabbed the wallaby, three pups emerged from the scrub to feed. Next day when Harry returned only the skeleton of the wallaby remained.

Harry believed that a thylacine would rip a hole in a sheep under the front leg where there was no wool and bore a hole into the rib cage in order to eat the internal organs. It would eat the kidneys, heart and lungs, and also take the meat off the back legs. A tiger, he said, could eat bandicoots and rabbits whole. It would catch bandicoots in tussocks, pouncing like a cat nose first, holding the tussock with its front paws as it pulled the prey out with its teeth.[22]

[1] ‘Priory: late Mr Joseph Clifford’, Examiner, 16 November 1932, p.5.

[2] Born 2 January 1856, birth record no.276/1856, registered at Fingal, RGD33/1/34 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=joseph&qu=clifford#, accessed 22 April 2019. For John Clifford as a convict, see marriage permission 31 March 1848, CON52/1/2, p.307 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=clifford&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriage+Permissions%09Marriage+Permissions, accessed 22 April 2019.

[3] Married 15 December 1879, marriage record no.656/1879, married at Georges Bay, registered at Portland, RGD37/1/38 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=joseph&qu=clifford, accessed 22 April 2019. Emma Clifford died 17 November 1937, aged 78, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery. The four sons were Joseph (born 1880), John (‘Ginger Jack’, born 1889), Henry (Harry, c1891–1974), James (1893–1920). The two daughters were Emma Ann Jane (born 1896) and Amy Florence (‘Florrie’) (1899–1923).

[4] ‘Priory: late Mr Joseph Clifford’, Examiner, 16 November 1932, p.5. Henry (Harry) Clifford died 19 November 1974, aged 83, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery. See will no.60025, AD960/1/151 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=henry&qu=clifford&isd=true, accessed 10 June 2020. James Clifford died 25 June 1920, aged 26, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery.

[5] ‘Shipping intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 19 August 1889, p.2.

[6] ‘Local and general’, Tasmanian, 24 August 1889, p.23; Robert Paddle, ‘The thylacine’s last straw: epidemic disease in a recent mammalian extinction’, Australian Zoologist, vol. 36, no.1, 2012, p.76.

[7] ‘Anson Marshes’, Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1922, p.6; Clifford family information from Deb Groves, 16 November 2019.

[8] John Morling, St Helens, interviewed by Deb Groves, 2019.

[9] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[10] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970.

[11] That is, 15 adults and 2 juveniles in the name of Josh Clifford, and 12 adults in the name of J Clifford. Josh Clifford: bounties no.283, 21 September 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.30, 6 March 1893; no.251, 16 October 1893 (2 adults); no.177, 10 July 1897 (5 adults); no.336, 23 November 1898 (‘5 November’); no.375, 12 January 1899 (‘5 December’); no.88, 27 April 1899 (’15 April’); no.375, 5 December 1899 (’13 November’); no.436, 27 September 1901 (1 adult and 2 juveniles, ’26 August’); no.354, 23 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO). J Clifford: bounties no.734, 11 January 1892; no.118, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.160, 5 July 1893 (2 adults); no.185, 10 October 1895 (2 adults); no.338, 31 July 1901 (5 adults, ’10 July’); no.984, 25 July 1902 (‘9 June’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO). For Joseph Clifford’s 1897 tiger killings see ‘The country’, Daily Telegraph, 22 April 1897, p.4; ‘St Helens’, Daily Telegraph, 23 August 1897, p.3; ‘St Helens’, Mercury, 27 August 1897, p.3.

[12] ‘Gladstone’, Examiner, 7 March 1905, p.6; ‘A heavy fine’, Examiner, 27 March 1905, p.5.

[13] Sarah Mitchell diary, 17 and 19 May, 9 and 26 June 1890 (University of Tasmania Special Collections).

[14] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[15] Jeff Richards, nephew of Harry Clifford; interviewed by Deb Groves. Jeff remembered Harry specifying that there were four or five young with the mother.

[16] John Morling, St Helens, interviewed by Deb Groves, 2019.

[17] Clifford family information from Deb Groves, 16 November 2019.

[18] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[19] Robert Paddle, ‘The thylacine’s last straw …’, pp.76 and 81.

[20] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[21] See Robert Stevenson to David Cunningham, 13 November 1941, QVM1/59, part 4, Inward correspondence 1941 (QVMAG). The same incident was reported in ‘Adventure with a native tiger’, Launceston Examiner, 22 March 1899, p.5.

[22] Harry Clifford, interviewed by Deb Groves, c1970.