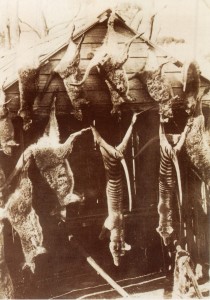

By the 1890s farmers like Joseph Clifford and Robert Stevenson were effectively adding Tasmanian tiger farming to their portfolios of raising stock, growing crops and hunting. Since thylacines appeared on their property, they made a conscious effort to catch them alive in a footer snare or pit rather than dead in a necker snare. A tiger grew no valuable wool, but in 1890 a live wether might fetch 13 shillings, compared to £6 for an adult thylacine delivered to Sydney.[1] A dead adult thylacine, on the other hand, was worth only £1 under the government bounty scheme.

The problem with these special efforts to catch tigers alive was that hunters only had a certain amount of control over what animals ended up in their snares or pits. Twentieth-century hunters often complained about city regulators who thought it feasible to close the season on brush possum but open it for wallabies and pademelons. Inevitably, hunters caught some brush possum in their wallaby and pademelon snares during the course of the season, which could land them a hefty fine in court unless they destroyed the precious but unlawful skins.[2] John Pearce junior in the upper Derwent district claimed that he and his brothers caught seventeen tigers in ‘special neck snares’ set alongside their kangaroo snares.[3] How did the tigers recognise the ‘special neck snares’ provided for their specific use? All you could do was vary the height of the necker snare to catch the desired animal’s head as it walked. Too bad if something else stuck its head in the noose. Wombats, for example, were a hazard. Gustav Weindorfer of Cradle Valley set snares at the right height to catch Bennett’s wallabies by the neck, but also caught wombats in them.[4] Wombats were good for ‘badger’ stew and for hearth mats but the skins had no value. Robert Stevenson of Aplico, Blessington, caught wombats alive in his tiger pits—which they then set about destroying by burrowing their way out.[5]

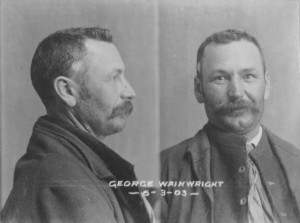

These problems aside, it seems odd that the pragmatic Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co), which later added fur hunting to its income stream, didn’t cotton on to the live tiger trade. They could have followed the example of George Wainwright senior, who sold a Woolnorth tiger to Fitzgerald’s Circus in 1896.[6] In 1900, for example, 22 thylacines were killed on Woolnorth, a potential income of more than £100 had the animals been taken alive. Even when, later, four living Woolnorth tigers were sold, the money stayed with the employees, with the VDL Co not even taking a commission. (It should be noted that four young tigers caught by Walter Pinkard on Woolnorth in 1901 were not accounted for in bounty payments.[7] It is possible that they were sold alive—but there are no records of a sale or even correspondence about the animals. Their fate is unknown.)

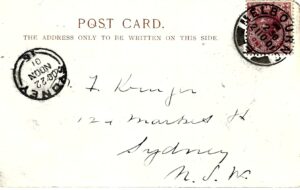

right, so far’. Did he get them from Woolnorth? Postcard courtesy of Mike Simco.

The VDL Co’s failure to exploit the live trade for its perceived arch enemy can possibly be explained by the tunnel vision of its directors and departing Tasmanian agent and the inexperience of his successor. James Norton Smith resigned as local manager in 1902. His replacement, Scotsman Andrew Kidd (AK) McGaw, harnessed Norton Smith’s 33-year corporate knowledge by re-engaging him as farm manager. It would not have been easy for McGaw to learn the ropes in a new country, among business associates cultivated by his predecessor, and the re-engagement of Norton Smith as his second allowed him to transition into the manager position. As would be expected, McGaw stamped his authority on the agency by criticising some of Norton Smith’s policies and distancing himself from them.[8] Ahead of Ernest Warde’s engagement as ‘tigerman’, the VDL Co’s shepherd at Mount Cameron West, he scrapped Norton Smith’s recent bounty incentive scheme of £2 for a tiger killed by a man out hunting with dogs.

After Warde’s departure in 1905, the tiger snares at Mount Cameron and Studland Bay were checked intermittently. Woolnorth overseer Thomas Lovell killed a tiger at Studland Bay in 1906, but the number of tigers and dogs reported on the property was now negligible.[9] This reflected the statewide situation, with only eighteen government thylacine bounties being paid in 1907, and only thirteen in 1908.[10]

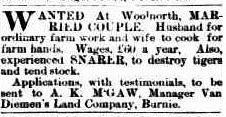

However, the value of live tigers continued to climb as they became rarer. The first documented approach to the VDL Co for live tigers came in July 1902 from AS Le Souef of the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne, who offered £8 for a pair of adults and £5 for a pair of juveniles. He also wanted devils and tiger cats, in response to which George Wainwright junior supplied two tiger cats (spotted quolls, Dasyurus maculatus).[11] Given the tiger’s reputation as a sheep killer, native animal farming might have been a hard sell to the directors, and the company continued to use necker snares which were generally fatal to thylacines. What price would it take to change that behaviour? In July 1908 McGaw read a newspaper advertisement:

‘WANTED—Five Tasmanian tigers, handsome price for good specimens. Apply Beaumaris, Hobart.’[12]

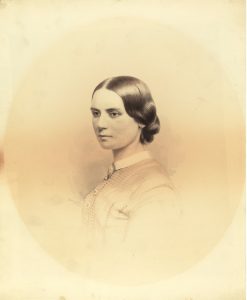

He discovered that the proprietor of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point, Mary Grant Roberts, wanted a pair of living tigers immediately to freight to the London Zoo.[13] The Orient steamer Ortona was departing for London at the end of the month. She offered McGaw £10 for a living, uninjured pair of adults. Roberts hoped to secure the tiger caught recently by George Tripp at Watery Plains, but felt that she was competing for live captures with William McGowan of the City Park Zoo, Launceston, who advertised in the same month.[14] Eroni Brothers Circus was also in the market for living tigers.[15]

Almost as Roberts made her offer, George Wainwright junior tracked a tiger at Mount Cameron West, but it evaded capture.[16] In the meantime Roberts was able to secure her first thylacine from the Dee River.[17]

Almost a year passed before the chance arose for the VDL Co do business, when in May 1909 Wainwright retrieved a three-quarters-grown male tiger uninjured from a necker snare.[18] Perhaps not appreciating the tiger’s youth, Roberts offered £5 plus the rail freight from either Burnie or Launceston. She wanted the animal delivered to her in Hobart within ten days in order to ship it to the London Zoo on the Persic. It would thereby replace one which had died of heat exhaustion in transit to the same destination a few months earlier.[19]

However, the overseer of a remote stock station could not meet that deadline. The delay came with a bonus—the capture of three more members of the first tiger’s family, his sisters and mother.[20] Bob Wainwright recalled his stepfather Thomas Lovell and brother George placing the animals in a cage. There was also a familiar story of tigers refusing to eat dead game: ‘They had to catch a live wallaby and throw it in, alive, and then they [the thylacines] killed it’.[21] With McGaw continuing to act as intermediary between buyer and supplier, a price of £15 was settled on for the family of four.[22]

Roberts and McGaw communicated as social equals, but their social inferiors—hunters, stockmen and an overseer—were not named in their correspondence. This made for frustrating reading when Roberts discussed hunters (‘the man’) with whom she was dealing over live tigers. She had been expecting to receive two young tigers from a Hamilton hunter for her own zoo, but these had now died, causing her to reconsider her plans for the Woolnorth family.[23]

It wasn’t until the first week in July 1909 that the auxiliary ketch Gladys bore the crate of thylacines to Burnie, where they began the train journey to Hobart.[24] A week later they were said to be thriving in captivity.[25] Roberts was so pleased with the animals’ progress that after eight months she sent a postal order to Lovell and Wainwright as a mark of appreciation. She was impressed with the mother’s devotion to her young, believing that the death of the two Hamilton cubs was attributable to their mother’s absence.[26] However, money was becoming a concern. Buying all the tigers’ feed from a butcher was expensive, and when she received a potentially lucrative order for a tiger from a New York Zoo, she found the cost of insuring the animal over such a long journey prohibitive. On 1 March 1910 she ‘very reluctantly’ broke up the family group by dispatching the young male to the London Zoo. ‘I am keeping on the two [other juveniles]’, she wrote, ‘in the hope that they may breed, and the mother all along has been very happy with the three young ones’.[27]

Roberts was now offering £10 per adult thylacine—but there was none to sell at Woolnorth. Seventeen months later she paid Power £12 10s for his large tiger from Tyenna, and scored £30 shipping to London the last of the three young from the 1909 family group.[28] Her tiger breeding program was over, probably defeated by economics—but what might have been the rewards for perseverance? Perhaps she would have been the greatest tiger farmer of all.

[1] See, for example, ‘Commercial’, Mercury, 5 August 1890, p.2; Sarah Mitchell diary, 9 June 1890, RS32/20, Royal Society Collection (University of Tasmania Archives).

[2] See, for example, ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[3] ‘Direct communication with the west coast initiated’, Mercury, 1 September 1932, p.12.

[4] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Journal of the Victorian Naturalists Society, vol.36, March 1920, p.159.

[5] Lewis Stevenson, interviewed by Bob Brown, 1 December 1972 (QVMAG).

[6] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[7] Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 19 July 1901, VDL22/1/27 (TAHO).

[8] In Outward Despatch no.46, 4 January 1904, p.366, McGaw criticised Norton Smith for not doing more to arrest the encroachment of sand at Studland Bay and Mount Cameron (VDL7/1/13).

[9] Woolnorth farm diary, 30 September 1906 (VDL277/1/34). This VDL Co bounty was not paid until the following year (December 1907, p.95, VDL129/1/4). C Wilson was paid for killing two dogs found worrying sheep in 1906 (December 1906, p.58, VDL129/1/4 (TAHO).

[10] See thylacine bounty payment records in LSD247/1/3 (TAHO).

[11] AS Le Souef to James Norton Smith, 11 July 1902; Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 4 August 1902, VDL22/1/28 (TAHO).

[12] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 July 1908, p.3.

[13] For Roberts, see Robert Paddle, ‘The most photographed of thylacines: Mary Roberts’ Tyenna male—including a response to Freeman (2005) and a farewell to Laird (1968)’, Australian Zoologist, vol.34, no.4, January 2008, pp.459–70.

[14] In ‘Wanted to buy’, Mercury, 18 July 1908, p.2, McGowan asked for tigers ‘dead or alive’. He had also advertised for ‘tigers … good, sound specimens, high price; also 2 or 3 dead or damaged specimens’ in the previous year (‘Wanted’, Mercury, 21 June 1907, p.2). George Tripp’s tiger must have died before it could be sold alive, since he claimed a government bounty for it (no.35, 25 July 1908, LSD247/1/3 [TAHO]).

[15] See, for example, ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 March 1908, p.6.

[16] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 17 July 1908, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[17] ‘The Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 7 October 1908, p.4.

[18] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 24 May 1909, VDL22/135 (TAHO). This thylacine was originally thought to be a young female, but McGaw later stated that it was a young male.

[19] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 31 May 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[20] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 1 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[21] Bob Wainwright, 86 years old, interviewed in Launceston, 27 October 1980.

[22] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 9 June 1909, VDL52/1/29; Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 10 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[23] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 21 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[24] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 7 July 1909, VDL52/1/29 (TAHO); ‘Stanley’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 July 1909, p.2.

[25] W Roberts to AK McGaw, 15 July 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[26] In May 1912 she received two young tigers from buyer EJ Sidebottom in Launceston, paying him £20 in the belief that they were adults. They died three days later (Mary Grant Roberts diary, 6, 7 and 10 May 1912, NS823/1/8 [TAHO]).

[27] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 14 March 1910, VDL22/1/36 (TAHO).

[28] Mary Grant Roberts diary, 12 August, 26 September and 24 December 1911, NS823/1/8 (TAHO).