In March 1886 the pastoralist Alfred Archer of Palmerston, south of Cressy, guided two Launceston schoolboys across the Central Plateau through poorly charted country to Lake St Clair.[1] This was the first in a series of extraordinary highland excursions for sixteen-year-old William Dubrelle Weston (1869–1948) and fifteen-year-old Ernest Milton Law (1870–1909). Later adventures would include probably the first bushwalk to the Walls of Jerusalem, visits to Great Lake and Mount Barrow, and the first two tourist trips to Cradle Mountain—‘the summit of our ambition’.[2]

On most of these expeditions they would be joined by two chums they knew from the Launceston Grammar School, the brothers Richard Ernest Smith (1864–1942), known as Ernest or ‘Old Crate’, and Alfred Valentine ‘Moody’ Smith (1869–1950). Weston’s letters from the period show the friends’ high-spirited camaraderie, and how hiking relieved the stresses of study, career, faith, self-discipline and social life during the transition from adolescence to manhood. Bushwalking was already popular in Tasmania, with accounts of highland excursions appearing regularly in newspapers.

Why did they choose Cradle Mountain in 1888? The peak received few visitors. No ascents are recorded between James Sprent’s trigonometrical survey in about 1854 and that by Dan Griffin and John McKenna in March 1882.[3] The discovery of gold on the Five Mile Rise on the western side of the Forth River gorge had increased traffic towards Cradle on the old Van Diemen’s Land Company Track, but the peak itself remained more remote from Launceston than even Lake St Clair was.

However, the Launceston Grammar old boys were now confident, independent bushwalkers. The Smith brothers were in charge of the commissariat. Alf was the hunter of the party, armed with a rifle. Currawongs and green parrots were landed on the way to Cradle Mountain, although a snake despatched by two weapons was left off the menu. Porridge, bread and butter, johnny cakes and beef fed the party at other times. Water proved so scarce that on the Five Mile Rise (near today’s Mail Tree or Post Office Tree on the Cradle Mountain Road) it was squeezed out of moss, a decoction that not even the addition of the emergency brandy and whisky could make palatable.

The party attempted to reach Cradle not by today’s tourist route across the Middlesex Plains, then south to Pencil Pine Creek, but by the direct route which took them into the deep, scrubby Dove River and Campbell River gorges. This was the hunters’ route to Cradle, but Weston’s party soon lost their way. With supplies dwindling on their fifth day out, there was nothing for it but to turn for home. Weston, who had taken to writing under the pseudonym of ‘Peregrinator’ or ‘Mr Peregrinator’, had been tantalised by Cradle’s ethereal heights:

‘Before us rose the imposing mass of the mountain; to our right was another stupendous gorge; and high above it and us a splendid eagle sailed in clam serenity, above all the ups and downs of terrestrial life and toil.’[4]

Ernest Smith wrote of the same vista months late: ‘I have that scene as vividly before me now while I am writing as if I were there, and I shall have until I die’.[5] There was no question but that they would return.

Two summers passed before ‘the old Company’ could reassemble, and they did it without ‘Moody’ Smith. ‘At last Mr Peregrinator and two friends got loose from their respective occupations’, Weston opened his second Cradle Mountain narrative. Infrastructure had improved in the three years since their last Cradle adventure. The Mole Creek branch railway, a new Mersey River bridge and the Forth River cage (flying fox) expedited travel. For a second time Fields’ Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley doubled as their official weighbridge. That this time their packs averaged about 49 lbs (22 kg) each, compared to 43.5 lbs (20 kg) on the previous trip, suggests heavier provisioning in an effort to secure their goal. Extra cocoa, ship’s biscuit, porridge, rice and tea probably came in handy—as did bushranger Martin Cash’s autobiography—when time lost to rain extended the trip to thirteen days.

The four chose the easier route via Middlesex Station, which proved a useful staging-post, and provided a stockman to guide them onwards. Like other early Cradle climbers, Peregrinator’s party mistook the more obvious north-eastern end of the mountain for the summit. They then had to dodge the series of intervening spires to reach the true summit at the south-western end, where they found the timber remains of James Sprent’s trigonometrical station.[6] Standing on Cradle’s pinnacle—the ‘summit of our ambitions’—in perfect stillness, with the island spread out below him, Weston struck a melancholic note:

‘We had been seeking grandeur of nature and now we beheld its plaintive softness … Sound, there was none. Yonder stood the frowning buttresses of the mountain … many a glistening silver line revealed a stream plunging in headlong fury down the distant slopes, and there asleep in the very arms of nature herself lay a tiny lakelet [probably Lake Wilks], whose breast was sacred e’en to the evening zephyr. How comes it that so much of this world’s intensest scenes of beauty are set in a minor key?’

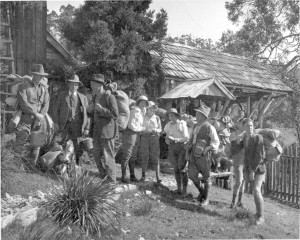

Sadly, Weston recognised that the party’s hiking career ended then and there on the summit. Now aged from 20 to 26 years, the men would soon sacrifice their youth and their physical prime to adult responsibilities. Yet Weston’s usual picaresque banter, historical footnotes and topical commentary enlivened their extraordinary ‘final push’ home—about 45 km from Middlesex Station to Sheffield by foot in a day. Peregrinator’s romantic description of the jewels of the night guiding his descent from the Mount Claude saddle must have raised eyebrows among those who knew the place only for labour with pack-horse and bullock team on their way to the gold mines on the upper Forth River. After alighting from the train in Launceston, the trio made straight for the photographer’s studio and there immortalised ‘the old Co’s’ swansong. ‘The closing scene was enacted some days later when we called for our proofs’, Peregrinator concluded.

‘On our appearance we were some time making our photographer perceive that we were the same individuals, who had called in with the black billies and aspiring beared a few days before. And now the Cradle trip like many like it remains a please reminiscence of the past and a joy for the future.’[7]

It is unlikely that Alf ‘Moody’ Smith, who became a Church of England minister in New South Wales, ever stood on the summit of Cradle Mountain. Ernest Law never repeated the adventure, dying, tragically, of typhoid in 1909, aged only 38. Neither Ernest Smith nor Weston renounced hiking altogether, with the former leading boys on mountain treks in his career as a school-teacher. But only Weston returned to the top. In 1933, 45 years after he first tackled Cradle Mountain and now 64 years old, he noted in the Waldheim Chalet visitors’ book at Cradle Valley:

‘With thankfulness to God’s goodness it is recorded that WD Weston who led the first Launceston party (late Ernest M Law and Mr Richard Ernest Smith) in December 1890–January 1891 (ascent Jan 2nd 1891) reascended to the trig on the Cradle 28th December 1933’.[8]

Ironically, the urban conqueror of Lake St Clair, the Walls of Jerusalem and Cradle Mountain more than four decades earlier, was now led to the summit by Overland Track guide Bert Nichols, a bushman fifteen years his junior. It is fitting that such an early spruiker of highland tourism should return to walk part of the ‘new’ track that popularised the region.

[1] ‘The Tramp’ (WD Weston), ‘About Lake St Clair’, The Paidophone, vol.II, no.7, September 1987, pp.7–8; ‘Shanks’ Ponies’ (WD Weston), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Launceston Examiner, 22 December 1888, p.2.

[2] See Nic Haygarth, “’The summit of our ambition”: Cradle Mountain and the highland bushwalks of William Dubrelle Weston’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.56, no.3, December 2009, pp.207–24.

[3] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Cradle country’, Tasmanian Mail, 8 February 1897, p.4.

[4] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Notes of a trip in the vicinity of the Cradle Mountain’, Colonist, 17 March 1888, p.4.

[5] RE Smith to WD Weston, date illegible, CHS47, 2/55 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [henceforth QVMAG]).

[6] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain: no.3’, Launceston Examiner, 4 March 1891, supplement, p.2.

[7] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain: no.5’, Launceston Examiner, 11 March 1891, supplement, p.1.

[8] Waldheim Visitors’ Book, vol.2, p.8, 1991:MS0004 (QVMAG).