Reinvention is part of the Australian convict story. Many convicts transported to the antipodes reinvented themselves as respectable society figures after serving their sentences. Joshua Anson’s surname was a byword for convictism, Anson being the name of a convict hulk which for years was stationed in the River Derwent, Tasmania. Born in Hobart with a hint of the stigma of convictism already attached to him on 29 October 1854, he would not only serve time and reinvent himself twice but he would pioneer convict tourism, making him almost a post-Modernist of the post-transportation era.

The second of three brothers born to Joshua Anson senior and Eliza Anson née Smith, Joshua Anson grew up to be a physically small man with large ambitions.[1] Unfortunately, his ambition as a landscape photographer shamed him before it famed him. In 1875, at the end of a three-year apprenticeship, 20-year-old Anson was placed in charge of his employer Henry Hall Baily’s Liverpool Street, Hobart shop, and offered an interest in the business. Anson was already a keen photographer, habitually rising at 5AM in order to utilise the morning light, and processing his own prints in his spare time in his home workshop.

About eighteen months after graduation as a ‘photographic artist’, however, Anson came under Baily’s suspicion. Four of the latter’s missing Souvenirs of Tasmania view albums were eventually found in Anson’s workshop. Further police searching revealed landscape and portrait prints, mounts and negatives stolen from Baily. Testimonials to Anson’s good character, including one from the photographer Samuel Clifford, failed to save him from a two-year gaol term for ‘larceny as a servant’.[2]

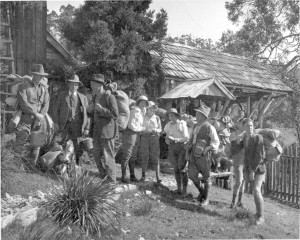

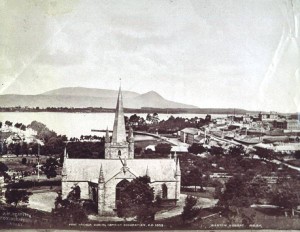

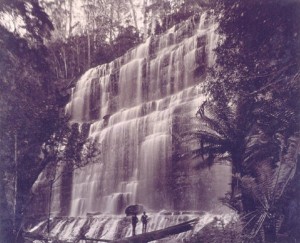

He served eighteen months—not at Gothic Port Arthur, but at the Hobart Gaol in Campbell Street. In July 1879, after his release, Joshua and his brothers Henry (1853–90) and William (1857–81) Anson established a photographic studio at 132 Liverpool Street, Hobart.[3] This had been Clifford’s address until 1878, and the Anson brothers seem to have acquired the Clifford photo stock. Joshua’s experience with Baily and his own previous photographic efforts presumably gave the brothers a head start in this new enterprise. He set to work with a series of 26 10-inch by 8-inch views of the Hobart and Launceston regions, including Silver Falls, Mount Wellington, Hobart and Launceston Main Line Railway Stations, Launceston’s Princes Square, People’s (City) Park, St Joseph’s Church and School (in Margaret Street, Launceston), Corra Linn and Cataract Gorge.[4] The immediate purpose of this exercise was probably submission of a dozen scenic prints to the Sydney Exhibition during August 1879.[5] The ultimate purpose would have been to establish a souvenir trade in Tasmanian scenic views. The Tasmanian newspaper reported that Anson would supply his new images to the public at a moderate price, and suggested that ‘if he would mount them in convenient portfolios, they would become popular with strangers, as souvenirs of their visit to Tasmania’.[6]

This is exactly what the Anson Brothers did. However, their biggest coup was recruiting Scottish immigrant John Watt (JW) Beattie, who became not only the shop manager but the firm’s leading landscape and portrait photographer. The Ansons needed help. All three were epileptics. Twenty-three-year-old William Anson died as the result of a swimming pool accident in 1881; Henry Anson, a married father, would eventually leave the firm but rely on Joshua’s financial help up until his death in 1890, aged only 36.[7]

Beattie has been credited with pioneering convict tourism in Tasmania, but the Port Arthur penal establishment was a subject of Anson photography from 1880, when it appeared in the firm’s Just the Thing photo album. The assumption that Beattie, who joined the Anson Studio two years later in 1882, infused it with his appreciation of history ignores the historical impulse that already existed among Hobart’s professional portraitists. It was almost obligatory in the 1860s and 1870s to photograph or paint the ‘Last of the Aborigines’. In 1880 Ansons photographed a 60-year-old pencil sketch of Hobart Town, featuring Aborigines, and both their ‘Photographs of Hobart and Surroundings, Huon Valley’ (1880?) and Tasmanian Views (1883) albums opened with a photo of the recently deceased Truganini, the former album giving her King Billy (William Lanne) as a consort.[8] . In 1884 ‘Mr Anson the photographer’ stepped off the fishing smack Surprise at Carnarvon, the sanitised name for Port Arthur, where he was reported to have shot several more Port Arthur images.[9]

Joshua Anson’s offer of partnership to his shop manager JW Beattie in 1890 not only demonstrates the high regard in which the latter’s services were held, but also Anson’s financial problems. Like many a businessman, he became bankrupt during the economic depression of the early 1890s. Court proceedings in April 1892 revealed that Anson had been in serious financial trouble for at least five months, struggling even to pay rent at his lodgings. [10] Part of his downfall was his speculation in shares in the Zeehan–Dundas mining field which had collapsed with the closure of the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land. He claimed to have little idea of the true state of the books until advised by an accountant, although this could have been a ploy to try to avoid culpability for his debts.[11] It was at this point that Beattie bought the Anson Studio, and with it the rights to all the Anson brothers photos taken not only by himself and Joshua Anson but the stock secured from Samuel Clifford. Many Anson Studio photos were re-branded ‘JW Beattie’.

Having lost his studio and his back catalogue, and still being subject to bankruptcy proceedings, Anson tried to re-establish himself as a photographer. Perhaps the strain showed when in March 1893 he was hospitalised with a head injury after collapsing during an epileptic episode in Collins Street.[12] He offered unsuccessfully to photograph lighthouses for the Marine Board of Hobart in July 1893.[13] He was finally discharged from bankruptcy in September 1893.[14]

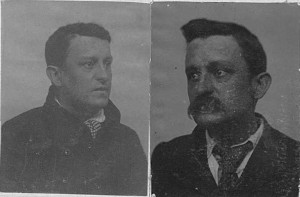

How did Anson make a living? It is possible he worked for Beattie in his old studio, their positions reversed. In October 1895 he failed in an application to recoup £25 from the government for some Tasmanian tourism photos which had been displayed in the Agent-General’s Office in London years before.[15] With that effort to start afresh defeated, Anson made no further public appearances until May 1896 when he returned to the dock after nineteen years on a charge of robbery from the person. He was alleged to have stolen almost £33 from Strahan storekeeper Charles Perkins at the bar of the Royal Hotel. Anson, who was arrested at Mrs Hanson’s boarding house in Collins Street, appeared in court with bruises on his face resulting from two epileptic fits suffered while in custody.[16] Two months later he was found guilty of receiving and sentenced to twelve months’ gaol.[17]

Anson’s rap sheet records the legacy of epilepsy, noting scars on both side of his forehead. He also had a disfigured left thumb and was missing a second toe from some mishap.[18] When it seemed things could get no worse for Anson, while he was in gaol a newspaper advertisement was run threatening to sell his uncollected clothes.[19] He was released on 26 July 1897: ‘freedom’ was the single word recorded on his rap sheet.[20] Whereupon he disappeared. There is no record of Anson living or dying in Tasmania after that date, although of course he could have changed his name. Forty-two years old, he had plenty of time to start a new career if bankruptcy and two prosecutions for dishonesty could not be held against him.

It is possible that he re-established himself in Western Australia. In November 1897 a John Anson proceeded against a photographer named Flegeltaub for wages due in the Police Court in Perth, Western Australia.[21] In July 1898 a ‘Mr Anson, a photographer engaged by the government to procure photographs of the district for railway carriages etc’, visited Bridgetown in southern Western Australia.[22] Two months later he was on a similar mission at Albany, procuring photos of the harbour, King Georges Sound, the Denmark forests, and in the York area. His employer was named as the Under Secretary of Railways.[23] Taking scenic tourism photos for the government would have been a familiar task for Joshua Anson, and mimicked Beattie’s on-going role as photographer to the Tasmanian government. In October 1904 a John Anson was initially named as one of seven people who went missing when a yacht called the Thelma disappeared in a squall off Fremantle. The men had set out with the intention of visiting Garden Island.[24] However, later reports of the same incident omitted Anson and put the toll at only six people. Joshua Anson may well have become Joshua Anon, reinvented itinerant landscape photographer, posthumous portraitist, a man without a past in a post-convict world.

[1] Birth registration no.1476/1854.

[2] ‘Supreme Court: Second Court’, Mercury, 11 July 1877, p.2; ‘Supreme Court: sentencing’, Mercury, 12 July 1877, p.3.

[3] The Hobart Assessment Roll, Hobart Town Gazette, 1 January 1878, p.36 places Clifford at 132 Liverpool St; whereas Charles Hartam is both owner and occupier of that property at 1 January 1879, p.35. Anson Brothers first advertised their 132 Liverpool St ‘(LATE “CLIFFORD’S”)’ studio in the Mercury on 30 July 1879.

[4] ‘Photographic views’, Tasmanian, 19 July 1879, p.11.

[5] ‘For the Sydney Exhibition’, Mercury, 22 August 1879, p.2.

[6] ‘Photographic Views’, Tasmanian, 19 July 1879, p.11.

[7] ‘Fatal accident at the Domain Baths’, Mercury, 16 February 1881, p.2; ‘The accident in the Domain Baths’, Mercury, 24 February 1881, p.3; ‘Sudden death’, Mercury, 26 March 1890, p.2.

[8] Charles Woolley, for example, submitted portraits of Tasmanian Aborigines to the 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition (Mercury, 25 September 1866, p.3), while HH Baily painted Truganini, the so-called ‘last queen’ of the Aborigines (‘Pictures for the Sydney Exhibition’, Mercury, 5 August 1879, p.2). For the pencil sketch, see ‘An interesting relic’, Mercury, 2 April 1880, p.2.

[9] ‘Carnarvon’, Tasmanian Mail, 19 April 1884, p.20.

[10] ‘Bankruptcy Court’, Launceston Examiner, 14 April 1892, p.3.

[11] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 24 May 1892, p.4.

[12] ‘Hospital cases’, Mercury, 17 March 1893, p.2.

[13] ‘Marine Board of Hobart’, Mercury, 29 July 1893, p.1.

[14] ‘Application in bankruptcy’, Mercury, 2 September 1893, p.3.

[15] ‘House of Assembly’, Mercury, 12 October 1895, p.1.

[16] ‘Alleged robbery’, Tasmanian News, 29 May 1896, p.2.

[17] ‘Second court’, Mercury, 29 July 1896, p.4.

[18] GD128/1/2, p.257 (TAHO).

[19] ‘Late advertisements’, Tasmanian News, 4 August 1896, p.4.

[20] GD128/1/2, p.257 (TAHO).

[21] ‘City Police Court’, West Australian, 9 November 1897, p.7.

[22] ‘Bridgetown’, Bunbury Herald, 2 July 1898, p.3.

[23] ‘England’s fleet’, Albany Advertiser, 13 September 1898, p.3; ‘York Municipal Council’, Eastern Districts Chronicle, 10 September 1898, p.3.

[24] ‘Disappeared in a squall: seven men missing’, Evening News (Sydney), 26 October 1904, p.4.