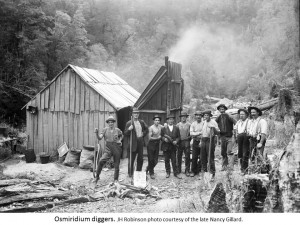

In November 1922 Nineteen Mile Creek osmiridium digger Charlie Prouse slapped a record-breaking lump of metal on the bar of Bischoff Hotel in Waratah, the nearest town. Prouse’s sale of his father Tom’s all-time-Tasmanian-record nugget probably brought them much needed, instant cash—and paid off their tab.

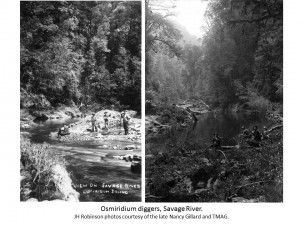

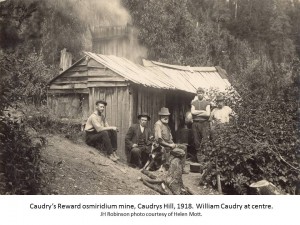

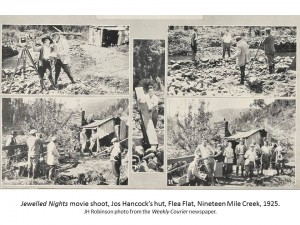

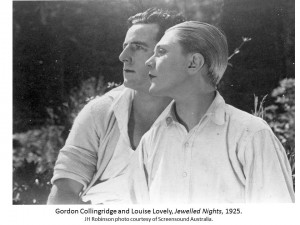

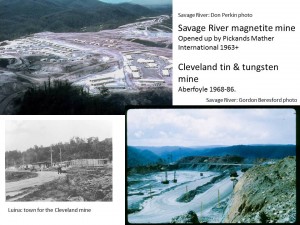

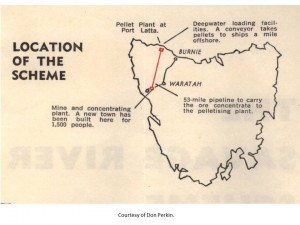

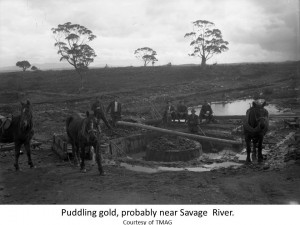

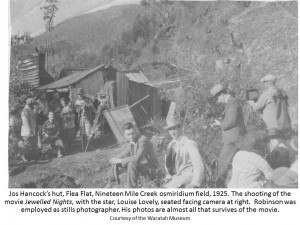

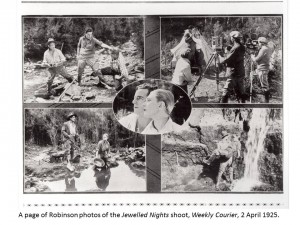

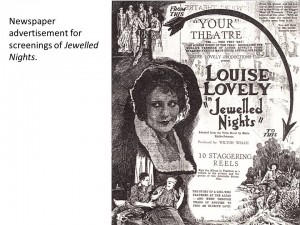

Metal as frontier currency fed into the old gold rush romance of a roistering wild west. This image and the rugged landscape appealed to Hobart romance writer Marie Bjelke Petersen, who found ‘nuggets’ of a different kind—human ones—on the ‘ossie’ fields. Some of her nuggets were female. In her best-selling 1923 novel Jewelled nights, gender bending on the Savage River osmiridium field enabled a Melbourne society belle to evade a marriage of inconvenience.[1] The runaway bride, Elaine Fleetwood, hid out on the Tasmanian frontier in the guise of a man, Dick Fleetwood. When, eventually, her clever disguise of slicked-down hair and dungarees failed her, the heroine submitted to fellow digger Larry Salarno, nature’s true gentleman. They married in nature’s own cathedral, a beautiful button grass area known as Long Plain, which today, unfortunately, is not quite so romantic, being occupied by the settling ponds of the Savage River iron ore mine.[2]

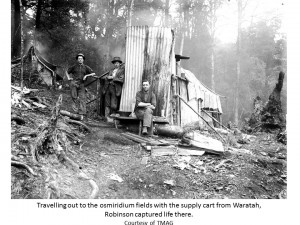

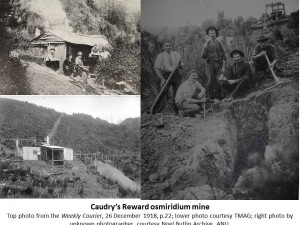

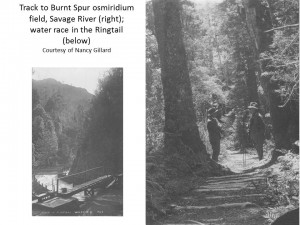

Bjelke Petersen was already a best-selling author when she wrote Jewelled nights. The irony of gushing heterosexual romance peddled by an unmarried virgin with a live-in female companion seems to have been lost on swooning young female fans across the English-speaking world. In the course of her research, Bjelke Petersen had established a reputation for venturing into the masculine realm at the frontier of civilisation. In 1921 she and her companion Sylvia Mills took a grand tour of the western mining fields. Based at the Whyte River Hotel, and with Vic Whyman as their guide, they had many thrilling experiences while visiting the Rio Tinto (Savage River bridge), Burnt Spur and Nineteen Mile osmiridium fields.[3] Bjelke Petersen gushed that

‘we often wondered if we should ever return. The precipitous mountain tracks were so dangerous, snakes were most numerous, we had to drive with horses that had never been in harness before, and were out in thunderous storms of tropical severity …’

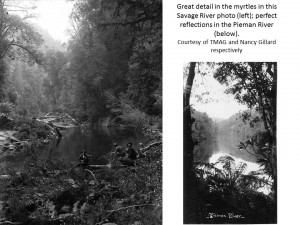

She claimed that on one occasion, only the intervention of Joe O’Connor, manager of the Jasper mine, saved the pair from being backed off the edge of a mountain track by a frightened horse during a storm. While crossing Long Plain en route to Burnt Spur, the author was struck by

‘the most gorgeous forests of giant myrtles and sassafras, the densest in the world, with alluring fern gullies and trickling streams, all along the five miles of awe-inspiring grandeur till the river was reached, deep down in the heart of a huge ravine’.[4]

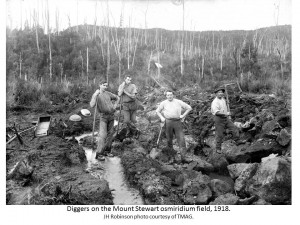

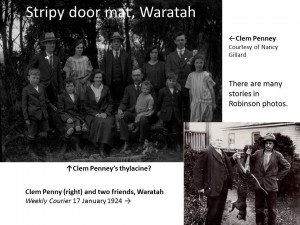

At Burnt Spur, where her novel was later set, she met one of the osmiridium field’s two women, Eva Tudor. A local legend, however, preferred another local, Frances Hazel Humphries, as the model for Bjelke Petersen’s heroine Elaine Fleetwood.[5] Humphries, born a girl and known by her middle name Hazel, eventually took a male name, wore men’s clothes, and performed traditionally male labour—including a stint on the Mount Stewart osmiridium field. Former Waratah resident Eric Thomas believed that as a young woman Hazel fell pregnant and, after having the baby at a Salvation Army maternity home, returned to Waratah as Frank Humphries, with hair brushed back and wearing a felt hat. He milked cows for the Penney family and delivered the milk by cart around Waratah. Thomas remembered that after a short stint working at Mrs Delphin’s ‘eat up shop’ in Waratah, Frank tried his hand at the osmiridium fields. It was there that Thomas met him while packing supplies for Tom Cumming and Ray Whyman.[6] In his book Taking you back down the track, Humphries’ contemporary Harry Reginald Paine recalled his ability with horses, cross-cut saw and pick and shovel.[7] In the years 1926‒31 Frank Humphries was an employee of the Burnie Dairy Co.[8] Later he became a Burnie shopkeeper, and ‘married’ a female partner with whom he relocated to Melbourne.

There were female diggers and miners’ partners on several osmiridium fields. Frank–Hazel’s story is more unusual yet, but there is no evidence of it being the inspiration for Marie Bjelke Petersen’s romance. It is unknown whether Bjelke Petersen even met Humphries. Yet one can imagine the novelist admiring a woman who refused, as Bjelke Petersen did herself, to conform to a prescribed gender role. Career, social standing and much wider scrutiny would have prevented Bjelke Petersen venturing beyond this role in Hobart—but the western mining fields, as the author found, offered a non-conformist almost anonymity. Perhaps that discovery was the real inspiration for Jewelled nights.

[1] Marie Bjelke Petersen, Jewelled nights, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1923.

[2] Button grass (Gymnoschoenus sphaerocephalus) is a native Tasmanian sedgeland plant so named because of its button-like seed heads.

[3] Vic Whyman claimed he was the singing coach driver who was immortalised in Jewelled nights. See Maggie Weidenhofer, ‘Marie Bjelke Petersen: forgotten writer of passion’, This Australia, Spring 1983, p.42.

[4] ‘In the wilds of the west’, Advocate, 29 January 1921, p.3.

[5] See Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, Somerset, 1994, p.98.

[6] Letter from Eric Thomas, undated, 1990s. The 1919 and 1924 assessment rolls show H Humphries occupying a cottage in North Street owned by HP McCreery (Tasmanian Government Gazette, 10 November 1919, p.2122; and 24 November 1924, p.2280).

[7] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, Somerset, 1994, p.98.

[8] ’15 witnesses examined yesterday’, Advocate, 2 September 1931, p.6.