A heartbreaking dedication is inscribed on a ceramic vase on one of the four marked graves in the Balfour Cemetery:

To Jim

good night love

may the night be short

that parts we two

Alma

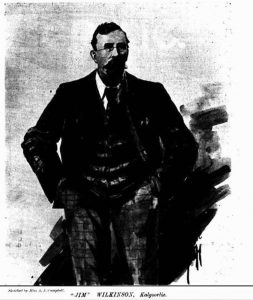

Big Jim Wilkinson stood almost 200 cm tall—6 foot 5 inches in the old measure. He was proof that even remote Tasmanian mining fields attracted not just local prospectors, labourers, miners, engine drivers and other skilled workers, but international adventurers, men who flitted between gold rushes and boom towns, revelling in the lifestyle, but who eventually settled into the more stable support industries that underpinned every mining field. Wilkinson, who supposedly counted Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, and the poet, Adam Lindsay Gordon, as friends, had been an imposing figure on the Kalgoorlie goldfield, being ‘a big power with the miners … He is one of the most popular men in Kalgoorlie, and deservedly so. He has a head like a Roman senator…’[1] He hadn’t quite made it into the Australian Senate, being defeated in two campaigns in Western Australia. He was also said to have made ‘a prodigious impression’ in Gormanston, ‘with his Uncle Sam beard, his diamonds, his earrings, and his accent which was very good American for a Victorian native!’[2] He had discovered gold on the Murchison field, kept livery stables and attained legendary status as a coach driver in the early days of the Silverton-Broken Hill silver field by keeping his passengers—or his horses, if he was carrying only freight—awake through the night with recitations of Gordon’s verses.[3] He had been a pearler, a guano dealer in south-east Asia, a race handicapper and a hotelier.[4]

Photo by Nic Haygarth.

However, none of that counted for anything at Balfour, where Wilkinson achieved another distinction entirely—he was the first interment in the cemetery, in January 1910, after only one month in town. He had come to Balfour to run a hotel for his brother-in-law, the ubiquitous jack-of-all-trades Frank Gaffney. Wilkinson arrived as a diabetic, in a shanty town that had no resident doctor.[5] Nor was there a minister to officiate at his grave. Like typhoid victims Haywood and Tom Shepherd before him, he died when there was no tramway from Temma. His grave relics—with their emphatic tale of loss and devotion—must have been hauled in from Temma by horsepower at least a year after his death. For more than a century, Big Jim Wilkinson, bright star of the boom-time, has rested in obscurity on one of Australia’s most obscure mining fields, leaving us to ponder the levelling power of death and the burning question—who was Alma?

*With thanks to Val Fleming.

[1] ‘Language freaks’, Critic (Adelaide), 26 March 1898, p.5.

[2] ‘Gormanston notes’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 27 October 1903, p.4.

[3] See, for example, Randolph Bedford, Naught to thirty three, Currawong Press, Sydney, 1944, pp.98–100.

[4] See, for example, ‘Death of Mr JJ Wilkinson’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus, 1 November 1910, p.15.

[5] ‘Resident doctor’, Examiner, 10 January 1910, p.5.