by Nic Haygarth | 16/06/17 | Tasmanian high country history

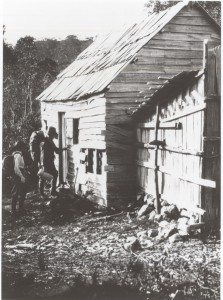

John Baptiste (left), a female visitor and a fellow digger at camp, Savage River, in 1924. Fred Smithies photo, NS573-4-4-1, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

John Baptiste, aka Hooky Jack, hides his metal hook hand, Savage River, 1924. Fred Smithies photo, NS573-4-2, TAHO.

Old Hooky was no new chum—

All his life he’d chased the gold.

And judging by his ‘skiting’

Won—and squandered—wealth untold.

He’d chased it in the Yukon,

In Alaska’s ice and snow,

And north from hot Coolgardie

Where the toughest only go.[1]

The toughest also tackled Tasmania, chasing osmiridium, and that’s where ossie digger Henry Humphries penned these words about his old mate ‘Hooky Jack’. The one-armed prospector, born as John D’Ahren Baptiste, spent at least three decades on Australian shores chasing everything that glittered. And he had a way of finding it:

A lucky man was Hooky and,

In truth, no matter where

He sank the most unlikely hole

There’d be some ‘metal’ there.[2]

Luck or skill? I fancy the latter. You don’t storm goldfields without learning the how, where and why of finding precious metals.

But who was Hooky Jack, and where did he come from? He is said to have inherited the equivalent of £30,000 ($60,000) in his home town of Madeira, Portugal, back in the 1880s, before embarking on his tour of world goldfields.[3] Perhaps squandering his inheritance was the start of a dissolute life, a rollicking refrain of tramp steamers, bars, brothels and all the trappings of the wild west.

It seems unlikely that Baptise made a fortune on Australian gold or Tasmanian osmiridium, although, admittedly, he is a hard man to track on local soil. Prospectors of a century ago often managed to elude electoral rolls, censuses and other public records. Although ships’ logs, gazetted mining leases and court cases are the historian’s allies, the John Baptistes of Australia take some sorting. Newspapers of his day bore so many references to the biblical John the Baptist, to St John the Baptist churches, guilds, fetes, lodges and French statesmen that following the prospector’s life is a painstaking affair. He wasn’t John Baptiste the Portuguese sailor executed for murder at Perth in 1900.[4] Nor was he the Sydney nurseryman John Baptist, and as for the Parisian sausage maker and confectioner from Wagga Wagga … let’s just say that these would be surprising career moves for a carousing wastrel.[5]

Happily, John D’Ahren Baptiste had some distinguishing characteristics which aid identification. One was his love of rum, another the colour of his skin. Baptiste was referred to as a ‘coloured gentleman’ and a ‘half caste’. There was hilarity in a North Melbourne courtroom when in 1895 he was summoned to answer a paternity suit. Baptiste’s defence submitted that the complainant, Annie Boddington, had no proof that he was the father of her newborn. Boddington’s response was to produce the dark-skinned infant, shouting, ‘Haven’t I! He’s a black man—and there’s no mistake about this lot’. The judge seems to have accepted this rather flimsy ‘evidence’, ordering Baptiste to pay maintenance.[6]

Baptiste’s most distinctive trait was his hook. Various prosthetics led the way on the osmiridium fields. ‘Peg Leg Ted’ Loughnan climbed Mount Stewart on one good leg to peg a reward claim in 1917.[7] Lost Adamsfield schoolteacher Tom Cole was tracked along the Gell River by indentations left in the soil by his wooden leg in 1938.[8] It helped carry him into eternity. Baptiste’s metal hook beat those wooden legs for versatility. It raked the fire, served as a fork in food preparation and hoisted the billy from the hot coals. He could saw with it, swing a pick and chop with it.[9] In a brawl he was even said to have used his hook as a club.[10]

Exactly how or when he lost his hand is unknown. Certainly he had the hook during his time on the Gippsland goldfields, Victoria, during the early 1900s.[11] Max Dyer described Baptiste as

‘probably the best miner to ever sluice gold along the Mitta Mitta. Folks used to say that Hookey [sic] could smell gold, as he was never known to have a useless claim. He had a drinking problem as well, and my mother had often told me of Hookey waving his hook in the air and cursing all and sundry … when he was in town on a bender. This only happened occasionally and when he was working his claim he gave it his undivided attention’.[12]

Yes, Hooky Jack knew his business and had plenty of nous. This was apparent when he arrived on the Nineteen Mile Creek osmiridium field nineteen miles west of Waratah. In 1914 stockpiling caused a dramatic slide in the osmiridium price, so he stashed nineteen ounces at the Waratah Post Office and returned to Gippsland, where he registered the Hard to Seek gold claim.[13] Negotiations over sale of that osmiridium stash continued while he was in New Zealand 1916–17, and he probably disposed of it in 1918 when the price almost doubled.[14]

With Russia engulfed in civil war, Tasmania suddenly had a world monopoly on the point metal osmiridium used to tip the nibs of gold fountain pens. Baptiste hit the new Mount Stewart ossie field in the foothills of the Meredith Range. Later he tried Savage River, working firstly with Harry Stanley, then with Charles Connors. His partnership with the latter ended in 1923 after the Portuguese spent nineteen days in the Waratah Hospital recovering from several blows to the head with a vase.[15]

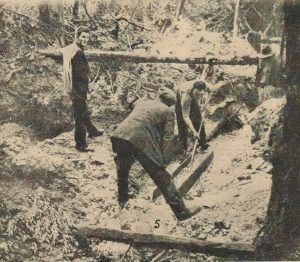

John Baptiste (back to camera) working a sluice box for osmiridium at Keep it Dark Gully, Adamsfield. From the Tasmanian Mail, 11 November 1925, p.40.

Baptiste fared better with former policeman Percy Marsh. The pair was among the first diggers to follow the Stacey parties to the Adams River osmiridium field in June 1925. There the Adamsfield poet ‘Mulga Mick’ O’Reilly claimed to have found Baptiste doing so well that he employed two men: one carried his stores in from the Florentine River, while another ‘did his cooking, fetched his whisky from the sly-grog shop, and put him to bed at night’. One report was that he sold his claim for a bottle of rum.[16] Another had Baptiste making £8000 in three months with Marsh at Keep it Dark Gully—a sly reference to his skin colour?—before selling the claim for £350.[17] Again, however, rum may have been his downfall, as he claimed to have been robbed of £200 of his winnings in Hobart in December 1925.[18] Perhaps this is what caused him to default on payments for a block of land at Prince of Wales Bay, Glenorchy, in 1927, losing his investment.[19] By then Hooky Jack was back on the west coast, prospecting for tin in the Norfolk Range.[20]

Baptiste was done with the ossie, but what happened to his winnings? Was it a case of easy come, easy go in a string of Hobart pubs and brothels? And what happened to him? He was not the supposed 64-year-old Frenchman John Baptiste who died at Broken Hill in 1938.[21] Nor did he go missing on the Great Depression gold trail like Harry Bell Lasseter. Baptiste appears to have seen out his days prospecting for gold in Gippsland, a naturalised Australian who passed the age of 80.[22] Perhaps, like Sammy Dwyer, last man at the Nineteen Mile, he was content to scrape a subsistence living from an old field he knew well, cooking in a camp oven, growing a few vegetables and reading about a world that had passed him by.

[1] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate (Burnie), 31 March 1962, p.13.

[2] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate (Burnie), 31 March 1962, p.13.

[3] ‘Along the “ossy” track’, News (Hobart), 10 September 1925, p.1.

[4] ‘The Ethel mutiny and murders’, West Australian (Perth), 18 June 1900, p.2.

[5] See, for example, ‘Progress of the suburbs’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 February 1914, p.8; and advert, Wagga Wagga Express, 15 August 1895, p.4.

[6] ‘A black bit of evidence’, Age (Melbourne), 18 October 1895, p.6.

[7] For Loughnan’s application for a monetary reward for his and Stanton’s discovery, see Edward Loughnan to Sir Elliott Lewis 23 December 1920, AB948/1/98 107B ‘Correspondence: osmiridium’ (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart).

[8] ‘Feared that missing prospectors have been drowned’, Advocate, 17 June 1938, p.6.

[9] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate, 31 March 1962, p.13.

[10] ‘Waratah assault case’, Advocate, 19 November 1923, p.5.

[11] The Commonwealth of Australia electoral rolls for 1903, 1908 and 1909, State of Victoria, Division of Gippsland, roll of electors for the Subdivision of Omeo, described John Baptiste as a miner at Mitta Mitta. In 1911 his 30-acre gold lease on the Bemm River, Gippsland, was gazetted as abandoned (‘Gazette notifications’, Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (Victoria), 2 September 1911, p.2). He was naturalised on 29 November 1911 at the age of 49, Victoria, Index to naturalisation certificates, no.12861, https://www.ancestry.com.au/interactive/60711/44441_346529-02210?pid=16656&backurl=http://search.ancestry.com.au/cgi-bin/sse.dll?_phsrc%3DAEX134%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource%26usePUBJs%3Dtrue%26gss%3Dangs-g%26new%3D1%26rank%3D1%26gsfn%3Djohn%26gsfn_x%3DNIC%26gsln%3Dbaptista%26gsln_x%3DNN%26msbdy%3D1865%26msbpn__ftp%3DPortugal%26msbpn%3D5184%26msypn__ftp%3DMelbourne,%2520Victoria,%2520Australia%26msypn%3D97862%26cpxt%3D1%26cp%3D2%26MSAV%3D1%26MSV%3D0%26uidh%3D2l5%26pcat%3DROOT_CATEGORY%26h%3D16656%26recoff%3D6%25208%26dbid%3D60711%26indiv%3D1%26ml_rpos%3D1&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=AEX134&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true, accessed 17 June 2017.

[12] Max Dyer, Hot air, bee stings & echoes: more bush yarns, the author, Bairnsdale (Victoria), 2006, pp.5 and 49.

[13] HB Silberberg to Bert Osborne, 8 May 1914, File 64-2-14, HB Selby & Co Papers (Noel Butlin Business Archive, Canberra); advert, Snowy River Mail (Orbost, Victoria), 11 December 1914, p.2.

[14] HB Selby to John Baptiste, 14 December 1916 and 19 January 1917, File 64-2-17, HB Selby & Co Papers (Noel Butlin Business Archive, Canberra);

[15] ‘Waratah assault case’, Advocate, 19 November 1923, p.5.

[16] MJ O’Reilly (‘Mulga Mick’), Bowyangs and boomerangs: reminiscences of 40 years’ prospecting in Australia and Tasmania, Hesperian, Carlisle (Western Australia), 1984 reprint, p.160.

[17] ‘The sifting out’, Examiner, 25 December 1925, p.5; ‘Adams River osmiridium field’, News (Hobart), 9 September 1925, p.1.

[18] ‘The morning after’, Daily News (Perth), 30 December 1925, p.1.

[19] Advert, Mercury, 16 November 1927, p.12.

[20] ‘Reported missing: prospector returns to camp, Mercury, 29 July 1927, p.6.

[21] ‘Wilcannia-Forbes Diocese’, Catholic Press, 22 September 1937, p.27.

[22] The Commonwealth of Australia electoral rolls for 1931, 1934 and 1943, State of Victoria, Division of Gippsland, roll of electors for the Subdivision of Leongatha, described John A Baptista as a prospector at Walkerville, via Fish Creek.

by Nic Haygarth | 09/12/16 | Circular Head history, Tasmanian high country history

Henry Thom Sing, from the Weekly Courier, 30 May 1912, p.22.

A downtown Launceston store is the face of a forgotten immigrant success story. The building at 127 St John Street was commissioned by Ah Sin, aka Henry Thom Sing or Tom Ah Sing, Chinese gold digger, shopkeeper, interpreter and entrepreneur. He was born at Canton, China on 14 March 1844, arriving in Tasmania on the ship Tamar in 1868.[1] Sing appears to have come from to Tasmania from the Victorian goldfields, and he was quick to seize on this experience when the northern Tasmanian alluvial goldfields of Nine Mile Springs (Lefroy), Back Creek and Brandy Creek (Beaconsfield) opened up. Like Launceston’s Peters, Barnard & Co, who hired Chinese miners through Kong Meng & Co in Melbourne, Sing began to recruit Chinese diggers on the Victorian goldfields.[2] His good English skills were an asset in trade and communication, and throughout his time in Launceston his services were drawn upon regularly as an interpreter in court cases involving Chinese speakers as far afield as Wynyard and Beaconsfield.

Circular Head farmer Skelton Emmett had been washing specks of gold in the Arthur River for years before a minor rush was sparked by two sets of brothers, Robert and David Cooper Kay, and Michael and Patrick Harvey, in April 1872.[3] Within three months, 160 miner’s rights had been issued and 70 claims registered.[4]

Claims were spread over about 2 km around the confluence of the Arthur and Hellyer Rivers. The European diggers generally preferred to work ‘beaches’ in the river.[5] Two European claims, the Golden Crown and the Golden Eagle, were on the Arthur downstream of the junction. The Golden Eagle party, who included William Jones and John Durant, strung a suspension bridge consisting of a single two-inch rope across the river in order to work both banks and for easy access: effectively it was a ‘bosun’s chair’ or flying fox. They worked their claim with a sluice box and Californian pump.[6] James West and party’s claim known as the Southern Cross was in a small gully on the southern side of the Arthur. The Kays’ claim was ‘in the gulch of a ravine’ a little further inland from the river. The claim of Frank Long, who later found fame on the Zeehan–Dundas silver field, was further down the same gulch.[7] The British Lion claim of W King was at the junction of the Arthur and the Hellyer, the Harvey brothers’ claim on the Arthur above it.[8] Waters from Circular Head and a man named House also held claims.[9]

Most of the gold obtained in the area by Chinese came from working the sand bars and shallows of the Arthur River. Sing had several roles on the field. Although Seberberg & Co had also engaged Chinese diggers for Tasmania, the 50 or so Chinese at the Arthur appear to have represented only two agents, Sing and Peters, Barnard & Co, both Launceston based.[10] Because he had a Launceston business to maintain, Sing’s time at the diggings would have been limited. He appears to have had two claims which were worked by Chinese parties, and he acted as an interpreter for other parties.[11] He also bought gold from diggers.[12] In November 1872, with the river low enough to permit an attack on its dry bed, both Sing parties engaged in ‘paddocking’, that is, diverting part of or the entire stream by damming it on their claim. On the upper claim the resulting wash dirt was put through a cradle, but the eight men expected to achieve better results when their sluice boxes were complete. Likewise, Lee Hung was building a sluice box.[13] The upper party once took 10 oz of gold in a day.[14] Wha Sing’s claim on the Arthur above the confluence included a vegetable garden, which would have provided his party with both food and cash, since stores would have been at a premium on the isolated field.[15]

One of the Chinese parties was said to have ‘turned’ the Arthur River in order to work its bed. While the Arthur is a large river, this is not as difficult an undertaking as it sounds. The idea is to drive a short tunnel or channel through a hairpin bend in the river, diverting its flow. A quick scan of the map makes it obvious where this could have been done. In fact the diversion channel would not have been on the Arthur River, but on the Hellyer, just above its junction with the parent river. This ingenious method of exposing a stream bed was employed on many gold fields and in Tasmania by osmiridium miners on Nineteen Mile Creek and other places.

The largest nugget obtained by February 1873―1 oz 3½ dwts―was found by a Chinese party in the river, but, generally, bigger nuggets were taken in the creeks.[16] Frank Long claimed to have got his best gold about 10 km from the Arthur River, and his was ‘much more nuggety’ than that of James West, who worked closer to the river. The gold appears to have been patchy. All the productive claims were above that of the Kays.[17] Working the creeks was harder in summer, but diggers made up for the lack of sluicing water by using chutes to bring the washdirt to the river.[18]

The Arthur River gold field was deserted by the end of 1873, and the Chinese soon switched to alluvial tin mining in the north-east. Sing built up his Launceston business. By the time he was naturalised as a British subject in 1882, he was renting a shop and residence at 127 St John Street, Launceston.[19] In 1883 he bought the site and erected a new premises designed by Leslie Corrie.[20] Here he sold imported Chinese groceries, ‘fancy goods’, preserved fruits, silk, tobacco, fireworks and the Chinese drinks and remedies Engape, Noo Too and Back Too.[21] Sing’s residence also served as a staging-post of Chinese tin miners arriving in Launceston. In 1885 he cemented his position in the north-east by buying out the store of Ma Mon Chin & Co at Weldborough, which afterwards operated as Tom Sing & Co.[22]

While a £10 poll tax was levied on Chinese entering the colony in 1887, Launceston’s established Chinese population became part of the community, with local businessmen Chin Kit, James Ah Catt and Henry Thom Sing supporting the work of the Launceston City and Suburbs Improvement Association by staging spectacular Chinese carnivals at City Park in 1890 and the Cataract Gorge in 1891. Fire gutted the Sing premises in 1895, and as a result it was either altered or rebuilt to the design of Launceston architect Alfred Luttrell.[23] This building remains today.

Sing married twice, and fathered at least seven children.[24] Both his brides appear to have been European. His death, in May 1912, aged 68, after 44 years in the Launceston business community, passed almost without comment in the Tasmanian press, perhaps indicating that, despite his naturalisation, a racial barrier between Chinese and Europeans remained.[25] Probate valued at £1738 suggested modest success.[26] Like the former Chung Gon store in Brisbane Street, today Henry Thom Sing’s St John Street store remains part of Launceston’s commercial sector.

[1] Naturalisation application, 22 July 1882, CSD13/1/53/850 (TAHO), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=tom&qu=sing, accessed 10 December 2016.

[2] ‘New Chinese diggers’, Tasmanian, 11 February 1871, p.11.

[3] ‘Gold discoveries at King’s Island and Rocky Cape’, Cornwall Chronicle, 29 April 1872, p.3.

[4] Charles Sprent to James Smith from Table Cape, 21 July 1872, NS234/3/1/25 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

[5] ‘The Hellyer goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicle, 22 November 1872, p.2.

[6] ‘Notes on the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 20 December 1872, p.2.

[7] ‘A look round the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 3 February 1873, p.2.

[8] ‘Notes on the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 20 December 1872, p.2.

[9] ‘The Hellyer gold-field’, Cornwall Chronicle, 16 December 1872, supplement, p.1.

[10] ‘The Nine Mile Springs goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicle, 13 May 1872, p.2; ‘Chinese immigration’, Tasmanian, 18 May 1872, p.8.

[11] See, for example, ‘More gold from the Hellyer diggings’, Tasmanian, 25 January 1873, p.12.

[12] ‘Table Cape’, Tasmanian, 25 January 1873, p.5.

[13] ‘The Chinese diggers at the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 November 1872, p.3.

[14] ‘The Hellyer goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicl,e 22 November 1872, p.2.

[15] ‘The Chinese diggers at the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 November 1872, p.3.

[16] ‘The Hellyer diggings’, Mercury, 13 February 1873, p.3.

[17] ‘Table Cape’, Cornwall Chronicle, 17 January 1873, p.3.

[18] SB Emmett, ‘The western gold field’, Launceston Examiner, 1 February 1873, p.3.

[19] Naturalisation application, 22 July 1882, CSD13/1/53/850 (TAHO), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=tom&qu=sing, accessed 10 December 2016.

[20] ‘Tenders’, Launceston Examiner, 26 July 1884, p.1..

[21] ‘Law Courts’, Tasmanian, 26 May 1883, p.563.

[22] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 19 September 1885, p.1.

[23] ‘Tenders’, Launceston Examiner, 7 March 1895, p.1.

[24] ‘Deaths’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1882, p.2; marriage registration no.966/1884, https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=henry&qu=thom&qu=sing#; accessed 10 December 2016.

[25] ‘Deaths’, Weekly Courier, 30 May 1912, p.25.

[26] Will AD96/1/11, LINC Tasmania website, accessed 10 December 2016.

by Nic Haygarth | 06/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Hydraulic sluicing on the north-eastern Tasmanian tin fields. O’Rourke’s hydraulic gold mine operated in the same manner. Stephen Spurling III photo, courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

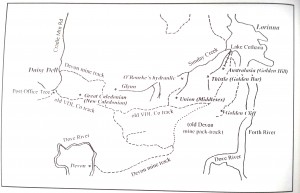

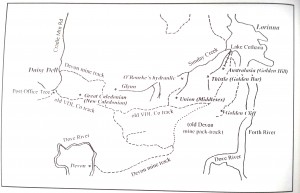

The Five Mile Rise goldfield, between the upper Forth River and the Middlesex Plains, north-western Tasmania, showing the position of the O’Rourke’s hydraulic gold mine.

Had Tasmanian miner Teddy O’Rourke been an interior decorator, he would have been a shoo-in for a colonial courtroom refit. His familiarity with magistrates’ chambers from Hobart to Deloraine, with dalliances at Kempton, Lefroy , George Town and almost a permanent booking in Launceston, must have been unsurpassed. Unfortunately, he was probably often too drunk to remember the decor. Yet Teddy also seems to have found a way to beat the bottle for two decades.

Edward Martin O’Rourke was born into an Irish Catholic family in Hobart in about 1856. A newspaper report of his mother Eliza (née O’Donnell or Donnell, a convict[1]) leaving home to escape violent attack by his father, ex-convict constable Martin O’Rourke (or Rourke), when he was an infant suggests that his was not a happy, comfortable childhood.[2] His education was probably rudimentary, as he remained illiterate.[3] By the time Martin O’Rourke drowned trying to ford the Forester River in 1876 at the age of 45, Teddy had at least five siblings.[4] It was after that that Teddy, along with his mother and sister Mary Ann Stratton, started making regular appearances in the Launceston Police Court, charged with assault (sometimes of each other), theft and drunk and disorderly behaviour.[5] The Jolly Butchers Hotel in Balfour Street kept by Eliza O’Rourke was the scene of some of this action.[6]

At the age of about 21 Teddy left Launceston for a rollicking lifestyle, racking up fines for public disturbances and learning how to handle a cradle at Brandy Creek, the alluvial goldfield that became Beaconsfield.[7] The only treatment he appears to have received for alcoholism was a stint in the slammer. One assault charge against him was dropped because his delirium tremens made him unable to testify.[8] Finally, in 1883, the judiciary lost patience and he got six months’ gaol for being idle and disorderly—followed by another three months for the same offence, this time in Hobart.[9] He served at least six terms in Hobart’s Campbell Street Gaol.[10]

Yet after 1892 O’Rourke stayed out of trouble for more than 20 years. Was mining his saviour? Men like Syd Reardon and Paddy Hartnett at Lorinna, 20 km from the nearest hotel, are said to have found an escape from the bottle in the bush. Perhaps Teddy’s experience on the Five Mile Rise when it was a diggers’ gold field in the 1880s was literally a sobering one.[11]

Then in about 1893 the New Zealand hydraulic craze hit Tasmania, and old gold fields like the Five Mile Rise got another trial, this time with the high-pressure hydraulic hose. Teddy O’Rourke took a claim on Sunday Creek, high up the Five Mile Rise, built a hut nearby and embarked on an unusual seasonal regime. Since it was only in the wet season that he could get sufficient water to operate the high-pressure hose, he combined hydraulic sluicing with hunting. April, May and June were the traditional hunting season. Prospectors and miners in the bush generally snared and shot animals for food anyway, but processing their skins for sale would have enabled O’Rourke to maximise (and perhaps sustain) his winters in the bush. A photo of what is probably O’Rourke’s hut taken by Fred Smithies shows that it was equipped with a skin drying chimney typical of those developed in the Cradle Mountain-Middlesex Plains area for the drying of possum and wallaby skins.

Teddy now revealed that not only could he make the press but he could use it. The secret to raising capital, apparently, was constant self-reference in the mining columns of newspapers. Harold Tuson grew up at Lorinna. In 1911, at the age of thirteen, he started work on gangs making tracks and roads in the upper Forth River region. During this time he came to know O’Rourke well as a fellow road worker, one of the latter’s summer jobs. He recalled the ‘big lump of a [Tasmanian-born] Irishman’ speaking with a thick Irish brogue. Having survived two or three bushfires, O’Rourke’s hut was then clearly visible from Lorinna high on the hill. Tuson recalled the miner’s struggle with alcoholism and his appearances in both the legal and mining columns of the newspaper: ‘“O’Rourke’s Hydraulic showing gold freely in the face”. That was one of Teddy’s. He’d write that to the paper to keep it going’.[12] Other stock phrases included ‘sluicing on payable gold’.

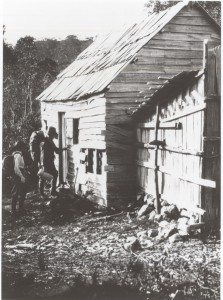

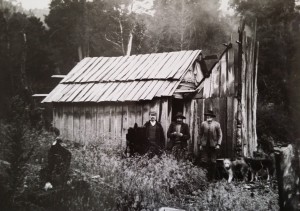

‘Hut at the top of the Forth Gorge track’, probably O’Rourke’s hut, showing the typical skin shed chimney favoured by Middlesex area hunters.

Fred Smithies photo, NS573/4/9/32 (TAHO)

O’Rourke’s hut stood near the beginning of the pack track down to the Devon mine in the Dove River Gorge. This pack track had become part of an extraordinarily steep route used by hunters to gain access to the Cradle Mountain region. On the southern side of the Dove River Gorge, the route continued up a steep hill known as Paddys Nut and crossed the Campbell River.[13] This was the route used by hunters Tom Jones and Bert Hansen in the winter of 1905 when the latter was tragically lost in a snowstorm near the lake near Cradle Mountain that now bears his name. Jones reported four-feet-deep snow as he began to make his way out to O’Rourke’s hut to raise the alarm, giving some idea of the conditions the gold miner experienced during these winter stints.[14] Since there are no mining reports to the press from O’Rourke in 1905, hunting may have been his primary activity during that wet season.

He also had business elsewhere. In 1904 O’Rourke had taken up a tungsten claim nearby, and by 1907 he was based at Ringarooma in the north-east, where he discovered the Montrose tin mine.[15] Later he turned his attention to the Colebrook tin field on the west coast, where he held a claim for a Launceston syndicate.[16] Meanwhile, in his absence, his hut on the Five Mile Rise was entered, robbed and forfeited to the Crown.[17] Thus the only property Ted O’Rourke ever owned was lost.

In 1911 he had a child, Edeline O’Rourke, with the recently widowed Annie Bissett (née Garrett) in Launceston.[18] She already had five children! Family responsibilities would have necessitated a steady income, hence, perhaps, O’Rourke’s work on the road gang. Eventually he may have got too old for bush life. Again, he was not at his best in town near the pubs. O’Rourke’s declining years contained a familiar litany of court appearances, including charges of disturbing the peace and vagrancy.[19] In 1919 the 63-year-old was found lying unconscious with a gashed head on a Launceston street.[20] In 1920 he was described as ‘an old habitue’ when defending a charge of being drunk and incapable in Albert Park on Christmas Day and in Charles Street a few days later.[21] He sported a scar over his left eye, perhaps as the result of some drunken escapade.[22] In 1922 he absconded when wanted for non-maintenance of his children, being tracked down in Deloraine.[23] In 1924, at 68 years of age, he was again found drunk and incapable in the street.[24] The trail of self-destruction stops there.

Like so many children of ex-convicts who could never escape the cycle of poverty and alcoholism into which they were born, Ted O’Rourke would have died intestate, with few possessions. His death stirred no comment in the press. Perhaps no one mourned his passing. However, I like to think of him as an innovator. He developed an unusual regime of hose, snare and, perhaps, teetotal, which kept him upright for two decades, drying out when the wet winter season brought his mining claim to life. That counts him as a success!

[1] Eliza O’Donnell was transported on the Midlothian. See permission to marry, 4 April 1855, CON52/1/7, p.408 (TAHO) and marriage certificate 473/1855, Hobart.

[2] ‘Local intelligence’, Colonial Times, 17 March 1857, p.3.

[3] Campbell Street Gaol Gate-book, warrant no.17591, 18 February 1889; records compiled by Laurie Moody; http://www.tasmanianwarcasualties.com/gravesofts%20split/Campbell%20Street%20Gaol/Rural%20Offences%20Part%209.htm

[4] See inquest, POL709/1/13, p.31 (TAHO); ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 20 January 1877, p.3. Martin Rourke was tried at Galway on 23 June 1848, sentenced to seven years, and came to Tasmania on the Lord Balhousie, being pardoned in 1855.

[5] See, for example, ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 21 September 1876, supplement p.2; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 November 1876, p.4.

[6] ‘Quarterly licence meeting’, Launceston Examiner, 8 August 1876, p.3; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 November 1876, p.4; ‘No true bill’, Launceston Examiner, 1 March 1877, p.2.

[7] ‘George Town’, Reports of Crime, 5 April 1878, pp.55–56.

[8] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 26 April 1882, p.3.

[9] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 12 November 1883, p.3; ‘City Police Court’, Mercury, 17 December 1884, p.2.

[10] Laurie Moody, ‘Campbell Street Gaol: inmates 1873–1890’, Tasmanian Ancestry, vol.26, no.2, September 2005, pp.24–30.

[11] Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[12] Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[13] See, for example, ‘North Western notes’, Mercury, 4 August 1905, p.2.

[14] ‘Cradle Mountain mystery’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 September 1905, p.2.

[15] ‘Iris River wolfram field’, Examiner, 20 September 1904, p.2; ‘Discovery of tin’, Examiner, 26 October 1906, p.2.

[16] See, for example, ‘Colebrook tin fields’, Examiner, 24 February 1912, p.4.

[17] POL386/1/1, Daily Record of Crime Occurrences – Sheffield 1901-1916 (TAHO).

[18] Birth registration 4877/1911, Launceston. See ‘Branxholm railway accident’, Mercury, 26 April 1910, p.2.

[19] ‘Police Courts, Hobart’, Mercury, 21 September 1915, p.6; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 3 November 1916, p.4; ‘City Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 13 April 1917, p.4; ‘City Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 18 June 1918, p.4.

[20] ‘An old age pensioner’s plight’, Launceston Examiner, 26 December 1919, p.4.

[21] ‘City Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 6 January 1920, p.2.

[22] ‘Prisoners to be discharged’, Police Gazette, 9 April 1920, p.69.

[23] ‘Persons enquired for’, Police Gazette, 23 June 1922, p.114; ‘Absconders’, Police Gazette, 14 July 1922, p.127.

[24] ‘City Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 15 December 1924, p.4.

by Nic Haygarth | 05/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Stanniferous drift is a term once used to describe tin-bearing ground, but it could just as easily describe the movement of tin mining families—or mining families of any other stripe—from one field to the next in search of better opportunities. Both economics and personal tragedy prompted depopulation of the small Middlesex mining field in north-western Tasmania around the time of World War I (1914–18). The contemporary photographs of bushwalker and national park promoter Ron Smith help tell the tale.

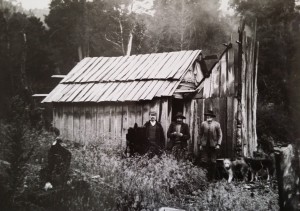

Hut at the Iris tin mine, April 1905. (Left to right) Les Smith, Tom Murphy and Richard Kirkham. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Wooden sluicing pipes, Iris tin mine, 1990s.

Hut at the Iris tin mine, 1990s.

In Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, Simon Cubit and I told the story of the three Davis brothers, Clarence, Sidney (Sid) and Edmund (Eddie), who came to Tasmania from Victoria and tried to farm the Vale of Belvoir near Cradle Mountain in 1903.[1] When the farming venture failed, Clarence Davis returned home, but Boer War veteran Sid Davis (1879–1913) and Eddie Davis (1888–1944) stayed on in the Tasmanian highlands, taking up the lease of the Iris tin mine near Moina.

Charlie and Charlotte Adam with their three eldest children, Bell goldfield, 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The Davis brothers’ partner in the mine was Charles Frederick Douglas Adam (c1864–1932).[2] Born in India as the son of an Anglo-Indian lieutenant, Adam had been sent home first to his parents’ house at Dover, England, to an aunt in France and to a Middlesex boarding school.[3] He is also said to have attended Eton, London and Cambridge Universities and the Sandhurst Academy—a busy schedule indeed, if it can be believed—before serving in the 81st Foot Regiment, with which he returned to India. Defective hearing prompted his retirement from the military, and he obeyed medical advice by settling in Australia. After a few years in Tasmania he arrived on the Bell Mount goldfield during the small rush there in 1892.[4] He made minor gold discoveries around the area at Golden Cliff and Stormont, and reworked the Bell goldfield when the hydraulic gold craze hit Tasmania. Charlie Adam married Charlotte Saltmarsh (1873–1946) in the nearby town of Sheffield in 1899.[5] They had children Charles William Guy Adam (1900), Mary Charlotte Adam (1902), Freda Kate Adam (1904), Frederick John Adam (1907), Robert Douglas Adam (1909) and Eileen.[6] There was also Charlotte’s daughter, Elsie (Elizabeth Mary Saltmarsh, born 1896), from a previous relationship.[7] Like many bush people, Charlie Adam used press subscriptions to keep up with the outside world, and his favourite was the weekly English illustrated newspaper The Graphic.[8]

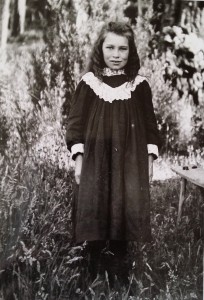

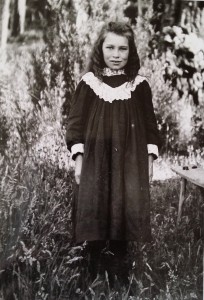

Elsie Adam, Bell goldfield, February 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

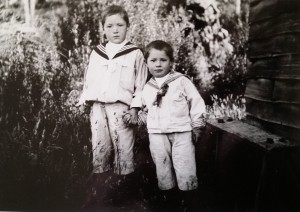

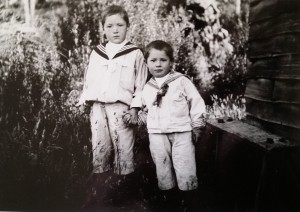

Guy and Mary Adam, Bell goldfield, February 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

However, at a time when there was no school at nearby Moina, the Adams’ most important education supplement was the tutor they employed, Mary Smith, to teach their three eldest children.[9] One of the things Mary taught was propriety. The manager of the biggest mine in the district was William Hitchcock but, offended by his surname, Mary pronounced it ‘Hitchco’. Did her silent ‘ck’ remove the problem or draw attention to it?[10]

Sid Davis came to dinner at the Adam house at the Bell goldfield, met Mary the tutor and began to court her. They married and established a farm at Black Jack, the long straight on what is now the Cradle Mountain Road south of Moina. From here Sid had a short walk to his other work at the Iris tin mine. The couple’s first child, Gladys, did not survive, but they had a second daughter, Hilda, in 1911, and another, Molly, two years later.[11]

Believed to be Sid and Mary Davis on their wedding day, 1909. Courtesy of Maree Davis.

Mary found the isolation difficult. Young Harold Tuson of Lorinna, on the eastern side of the Forth River, found out how lonely she was. In contrast to Charlie Adam’s highly regimented upbringing, this thirteen-year-old had just entered the workforce on a road gang, building the Cradle Mountain Road, and was camped near the Davis house. While returning home for the weekend he ran into Sid Davis on the road:

I suppose he wanted someone to talk to … ‘Where did you come from? And what do you do?’, and … he said, ‘Call in’. Little two-room place on the left … ‘Call in and have a talk to the wife. She’s very, very lonely’. And so on the Monday I did [call in]. And I’m carrying a songbook and she and I got to work and were singing … and I decided I’d better go and she wouldn’t allow me, she didn’t want me to go. ‘Sing another song …’[12]

In 1912 Gustav and Kate Weindorfer established Waldheim Chalet, their tourist resort at Cradle Valley. Charlie Adam was one of their first guests, but Weindorfer also availed himself of the Davises’ hospitality when caught on the road in bad weather. On more than one occasion he rocked young Hilda Davis to sleep in her cradle.[13]

On 14 May 1913 Sid went to work as usual at 7 am. Two-year-old Hilda accompanied her father to the gate. The family’s dog, Bob, followed at Sid’s heels until Mary called him home. She was busy in the kitchen four hours later when she heard a horse galloping up to the house, followed by a knock at the door. It was her friend, a lady named Ward, a frequent visitor. Imagining that she had bad news to impart, Mary immediately thought of her mother. ‘Don’t tell me’, she cried, ‘go and tell Sid!’ ‘I can’t’, her visitor replied, ‘he’s dead’.[14]

Sid Davis had been working in the open cut when a tree stump fell on top of him, striking him fatally on the back of the head. He had survived guerrilla warfare in South Africa only to succumb in a mining trench in peacetime. ‘It was such a blow to Mum, really and truly’, Hilda Davis recalled,

She never got over it … She was always thinking of her days at the mine and of Dad. She never got it out of her system. She loved those days up there …[15]

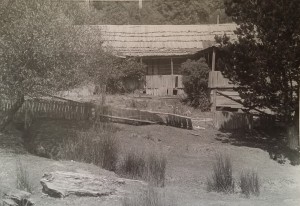

The abandoned Adam house at the Bell goldfield, February 1926. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

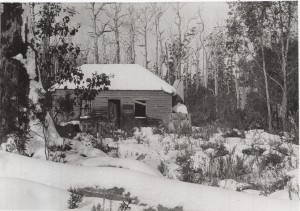

The deserted Davis house at Black Jack, Cradle Mountain road, August 1925. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Mary Davis tried to keep the Iris mine going, but having a four-month-old child at her breast made it impossible. Tin mining was scuppered by World War I soon after. There was an exodus from the small mining field. Mary Davis tutored children in Sheffield, but eventually returned home to her parents. Eddie Davis married Moina postmistress Lil Gurr, with whom he adjourned to Melbourne.[16] Elsie Adam married miner Watty Davis at her parents’ house but set up home at the tungsten and tin village of Storeys Creek.[17] Charlie and Charlotte Adam moved to Waratah, but eventually resettled in another mining region, the Latrobe Valley, Victoria. Three other Adam children settled in mining towns.[18] By the mid-1920s both the Adam and Davis houses, where so many children had grown and so many lives had intersected, were ruins. Of the characters of this story, only Gustav Weindorfer, the widowed proprietor of Waldheim Chalet, remained trying to eke a living from the mountains.

[1] Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.18–23.

[2] Australian Death Index, registration 13455/1932.

[3] British Census, 1881, Middlesex, Finchley, District 1, p.54. His birthplace was given as India; ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[4] ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[5] Married 10 May 1899, marriage registration 962/1899, Sheffield.

[6] Birth registrations 2326/1900, 2391/1902, 2518/1904 respectively. Frederick John Adam’s death certificate (7866/1972, Victoria) give his year of birth as 1907. Robert Douglas Adam’s World War II military record gives his date of birth as 29 January 1909, place of birth Moina. Eileen Adam is mentioned as a surviving child in Charlie Adam’s obituary, Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[7] Born 27 August 1896, birth registration 2328/1896, Sheffield.

[8] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[9] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991. Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995, remembered Mary Smith as being the tutor for William and Kate Hitchcock at Moina.

[10] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[11] Rose Ellen Gladys Davis was born 8 January 1910 and died 8 April 1910, birth registration 5417/1910, death registration 928/1910. Hilda May Davis was born 2 March 1911: Molly Davis was four months old at her father’s death: both facts from interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[12] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[13] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[14] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[15] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[16] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[17] See ‘Wedding bells’, Examiner, 12 April 1920, p.6.

[18] ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 30/10/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Hedley Higgs at his Narrawa Creek gold mine. No, he’s not cross dressing … that’s a metalworking apron. Photo courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

For many people the Wall Street crash of 1929 heralded an era of making do with very little. Some families still earned a crust on the mining fields. In 1931 the pound was devalued, causing a spike in the fixed price of gold.[1] Wallets sprang open like blooms in a drought-breaking downpour. On the small Middlesex mining field in north-western Tasmania new money was pumped into the old Great Caledonian gold mine. William Aylett made grand claims for the old Lea River gold mine.[2] Two-hundred-and-twenty acres were taken up on Black Bluff to work the old Devonport Prospecting Association gold mine.[3] Fossicking near the old Narrawa Creek gold mine in August 1934, Devonport mechanic Hedley Higgs (1885–1980) found extremely find gold in the roots of an upturned tree.[4]

Higgs was an engineering prodigy. He had the same love of gadgets, bikes and engines that characterised his Launceston contemporaries such as Stephen Spurling III, HJ King and Fred Smithies. However, unlike them, he did not take up photography. The Higgs family were well-known shipbuilders at the Mersey River, and Hedley was a skilled yacht builder and yachtsman. He was also an expert marksman. As a young man he zipped about on a Harley Davidson, managed his own motor garage and fixed motorbikes for the self-proclaimed Launceston ‘bike king’ Sim King.[5] The grandson of the Tasmanian amateur scientist AB Biggs, Higgs had repaired radios, tried to patent an explosive and blown himself up with acetylene gas by the time he got to the mining game.[6] He knew nothing about mineral processing until he was asked to build a plant for the Stormont bismuth mine in the early 1930s. Of course his plant was a success, but the mine was forced to close when the Iris River bridge was burnt out.[7]

Now Higgs started forking the Narrawa Creek gravel through sluice boxes. His journal entries demonstrate that mining was sometimes hazardous: ‘Lost ½ plug of gelignite warned men’.[8] Gold recovery was testing: ‘Finished cleaning up for a little under 4 oz. Gold looks clean and has a lot of larger pieces in it. Paddock worked in hollow below pines on race, amount sluiced about 110 yards but a lot of gold left on the bottom!’[9] Ingenuity was always required: ‘brought back old sterilizer from Devon Hospital …’[10]

Higgs with his home-made gold battery. Photo courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

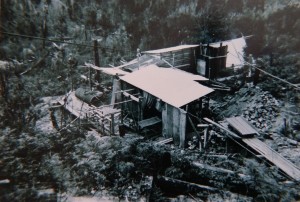

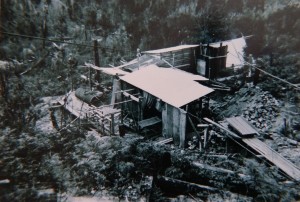

The experimental plant at Narrawa Creek. Photo courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

Then in 1935 Higgs rigged up a battery to crush the ore. Old Ford car axles became rods for the stamper battery. Even a bicycle was introduced to the works.[11] The machinery was driven by a seven-horsepower oil engine.[12] However, he still needed water for sluicing, and the weather did him few favours. Summer offered little rain, in winter it snowed.[13] Nor were the natives necessarily helpful or friendly. In March 1936 Higgs collided with two men riding a motorbike, damaging his car. ‘Reported accident to police’, he noted, ‘renewed permit to carry pistol …’[14] In the following year, one of his employees at the mine, Harry Lawson, was shot dead in a dispute over hunting territory.[15] Another, Dick Nichols, had a shot fired into his house after taking up with another man’s wife.[16]

Early sluice box and battery clean-ups were promising. By 1937 the mine had produced 188.5 oz of gold from the treatment of 1118 tons of ore.[17] Higgs drove an adit to cut the lode at greater depth, but when the oxidised zone gave way to sulphide ores, he was left with hard galena and pyrite.[18]

In the late 1930s the Public Works Department built a road down to the mine. Photo courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

When World War II started, the price of tungsten, used for hardening steel in munitions, soared, and Higgs turned his attention to the adjacent Squib tungsten and molybdenum mine, last worked when prices were high at the end of World War I. Everything went well until payday came at Christmas—and the mainland company had only £20 in the kitty.[19] Hedley Higgs’ brief flirtation with mining was over.

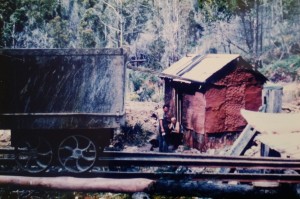

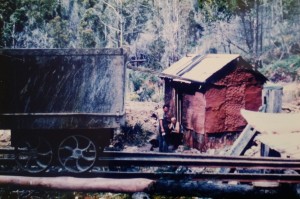

Keith Harvey and Arthur Goldsworthy at the Sunrise mine in the early 1960s. Roxley Day photo.

Another shot of the Sunrise operation from the same period. Roxley Day photo.

The somewhat battered Sunrise hut still standing in 1993.

Metal wheel at the Higgs/Sunrise mine site in 1993. In his archaeological report, Parry Kostoglou suggests this could be part of an ore disintegrator.

But the Higgs gold mine was not dead. It was worked as the Sunrise mine in the 1960s by Keith Harvey and Arthur Goldworthy, the latter being a member of an old Cornish family who had come to Moina via the Moonta copper mine in South Australia’s ‘Little Cornwall’ and the Beaconsfield gold mine. Inevitably, it was reworked yet again during gold’s upward parabola after the US government placed the precious metal on the open market, churning up any evidence of Hedley Higgs’ home-grown gold plant.

[1] Geoffrey Blainey, The rush that never ended: a history of Australian mining, 5th edn, Melbourne University Press, 2003, p.307.

[2] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.52–53.

[3] ‘Middlesex gold: mainland company interested’, Advocate, 7 November 1936, p.10.

[4] Interview with Sheila Slowan, daughter of Hedley Higgs, East Devonport, c1993.

[5] Motor vehicle registrations, Police Gazette, 10 December 1920, p.237.

[6] Devon News, 20 August 1964 (newspaper clipping obtained from Sheila Slowan).

[7] Devon News, 20 August 1964 (newspaper clipping obtained from Sheila Slowan).

[8] Hedley Higgs journal entry, 9 February 1935, courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

[9] Hedley Higgs journal entries, 23 and 23 May 1935, courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

[10] Hedley Higgs journal entry, 9 March 1936, courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

[11] Interview with Sheila Slowan, daughter of Hedley Higgs, East Devonport, c1993.

[12] ‘Unique battery at Middlesex’, Examiner, 16 January 1936, p.8.

[13] Hedley Higgs journal entries, 27 January 1935 and 13 June 1936, courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

[14] Hedley Higgs journal entries, 8 and 9 March 1936, courtesy of Sheila Slowan.

[15] See ‘Twelve witnesses examined …’, Advocate, 11 May 1937

[16] Higgs alluded to this well-known incident in an interview with Kerry Pink, ‘A couple of “old timers” with no time for idleness’, Advocate story, details unknown. Nichols was listed as employee in Higgs’ journal, held by Sheila Slowan.

[17] F Blake, ‘Higgs’ gold mine—Narrawa Creek’, Unpublished Department of Mines report, 1937; cited by AE (Tony) Webster, An archaeological survey of the Higgs gold mine, near Moina, north-western Tasmania, Mining Geoscience, 1998, p.5.

[18] ‘Middlesex fields’, Mercury, 8 July 1936, p.4.

[19] Kerry Pink, ‘A couple of “old timers” with no time for idleness’, Advocate story, details unknown.