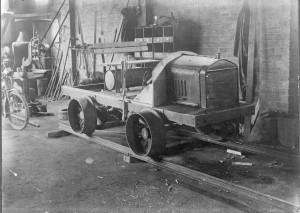

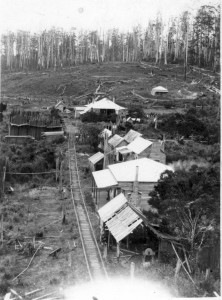

‘Manuka’, originally known as ‘Glen Valley’, was built by Elijah Britton for his family at Brittons Swamp, with the help of his cousin Fred Britton and a plumber, Jack Bailey. The blackwood and hardwood for the inside walls and floors were air-seasoned, then dressed with a steam planer. Elijah’s one failing was brickwork, his chimneys leaving much to be desired. Nevertheless, in April 1922 the house was christened:

HOUSE-WARMING. — Mr E Britton has built a spacious residence at Christmas Hills. On Easter Saturday night the residents wended their way to give Mr and Mrs Britton a house-warming. A very pleasant evening was spent and cheers were given for Mr and Mrs Britton. During the evening items were rendered by Mrs P Streets, Miss E Dunn, and Messrs S Rowe, O Murphy, T Hine, A Rowe, R Dunn, and E Rowe. Excellent music for the dancing was supplied by Mr Y Wilson. Mr P Streets very capably carried out the duties of MC.[1]

This was long before electricity or sewerage came to the bush. The toilet was a kerosene tin in a little hut behind the house. Once or twice a week the kerosene tin was emptied, the effluent being buried in a hole.[2]

The mill workers’ cottage vacated by Elijah’s family became Mark Britton’s quarters, where he slept and did the office work. Once a year Lorna washed his blankets and scrubbed his dirty floors. Mark was in the habit of piling bark, sticks and firewood against the inside wall of his office. ‘This was clean dirt, so I’d take that out and scrub that room, but the bedroom was the worst’.

‘Our home was his real home’, Lorna remembered. ‘He had his special place at the table and sat one side of the fireside of an evening in the lounge chair opposite Father all the years he lived with us’.[3]

Right from the start, Annie had recognised the need to diversify and, especially that farming, as well as timber, was needed to sustain her family. Her duties in the home were so many and so laborious that she was run off her feet. Even as her children were growing up and leaving home, Annie suffered with quinsy and a sore throat. She had her tonsils removed late in life in hope of fixing the latter problem. During the winters, her seasons of greatest suffering, the burden of the housework and childcare fell upon her eldest daughter Lorna:

Mother was either too sick or too busy to give the children much love, and I lavished all my affection on those kids. I never knew Mother to be affectionate to me or Phil, and we missed out there.

I was amazed to hear someone say they didn’t know I did anything other than play the violin and piano, paint, and be a lady. Maybe I did when they knew me, but who did the helping where there was no hot water and electric power and light? I would do the last tea dishes in a dish of hot water on the kitchen table by the light of one candle, and put away the meat that came late. It had to be lightly salted and put in the meat safe in a cool place. Mother would already be in bed, and I’d still be working till 8 or 9 o’clock.

Lorna remembered the young Ken as ‘The Little Comforter’ because with a twinkle in his eye he could bring a smile to Annie’s face

He loved the farm animals and could find a calf that had strayed or been hidden by its mother, or a hen’s nest. At that time the common swear word was ‘cussed’, heavily emphasised. I never heard my father, uncle or brothers swear, so Ken came running in at the lisping stage, clutching an egg and shouting ‘I heard a dusserd hen dackle, and I runned over and bruted her off the nest’. It was a favourite saying around the mill for a long time and caused many a happy moment.

The next-youngest boy John was ‘a frail little chap’ who developed eczema so badly that, despite medical treatment, Lorna feared his earlobes would drop off:

But he survived, and I cared for him until I was sent away to school in Launceston for one year. When I left school he was still weak and sickly, suffering many colds and Mother and I sat up more nights than I wish to remember when he had croup and we tried with limited medical care to ease his suffering.

One night he was so distressed that Mother, with her face set in anguish, left the room and brought in a spoonful of something which she poured down his little throat and soon brought relief. What it was I never really knew, but it was probably something that her mother had given her as a child. I think the mixture contained turpentine.

Both feared he would not ‘make old bones’, but John would prove them wrong.[4] Unfortunately, to do so, he would have to survive an accident in which his legs were crushed.

As Elijah and Annie’s children grew, the role of mail and meat bearers fell to Eva, Frank and Ken in turn. By that stage the house the Brittons formerly occupied at Christmas Hills had been enlarged to become the new school, and a public hall had also been raised nearby by public subscription. In 1922 the school graduated from a subsidised school to an ordinary state school, with Irene Dunn continuing as teacher.[5] It was in the unfinished school building that 15–year–old Lorna Britton was farewelled when she left for Launceston to finish her education at Broadland House Ladies’ College (now part of Launceston Church Grammar School):

Dancing was the order of the evening … a presentation of an Xylonite brush and comb and a very handsome box of writing material was made by Mr. C. Burton on behalf of the residents of Christmas Hills to Miss Britton to remind her of those she was leaving behind. Mr. Roy [sic: Phillip Raymond] Britton on behalf of his sister, thanked all for the kind wishes and the presents given to Lorna. The singing of “For she’s a jolly good fellow” terminated a very enjoyable evening.”[6]

[1] ‘Christmas Hills’, Circular Head Chronicle, 26 April 1922, p.3.

[2] Frank Britton memoir, 16 December 1992 (QVMAG).

[3] Lorna Britton notes1983.

[4] Lorna Britton notes 1983.

[5] ‘Xmas Hills Picnic Sports’, Advocate, 21 March 1923, p.6.

[6] ‘Christmas Hills: farewell’, Circular Head Chronicle, 14 February 1923, p.2.