The Adamsfield sly-grog shop was anything but sly—on the contrary, it was an open secret. Commonly known as ‘The Boozer’ and ‘The Miner’s Delight’, it functioned so long as there were thirsts to be quenched, livelihoods to be drowned and punches to be thrown. For two decades it was the toast of south-western Tasmania. The greatest bottle dump in south-western Tasmania attests to osmiridium diggers’ habit of pissing their winnings away.

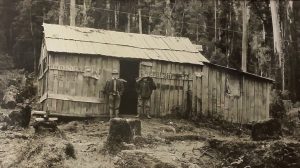

Control the liquor, and you control the town—or so the theory went. In the absence of police, church, bank and any moral authority apart from a committee formed by the diggers themselves, a licensed hotel was surely the key to controlling the reputedly 800- or 1000-man-strong Adams River osmiridium rush of 1925. So it was that in December of that year a licence was granted to well-known publican Eldon Joseph. Lot 10 in the newly surveyed township of Adamsfield was set aside for his establishment, but it burned down during construction and never opened.[1] In its place, Bernie ‘Saviour’ Symmons, as he was known, built a billiard room and sly-grog shop which occupied Lots 9 and 10. Symmons’ partner was Ralph Langdon, and there was a bit of history between them. Langdon had previous convictions for running Hobart gaming houses, including one with Symmons.[2] When the Adams River rush began the pair first operated a ‘refreshment’ hut—that is, a sly-grog and accommodation house known as ‘The Digger’s Rest’—as the first staging post along the 42-kilometre track.[3] Gladys Langdon was the cook and manager there.[4]

Now Symmons and Langdon were doing the same thing in Adamsfield itself. This establishment, known officially as Symmons’ Hall, was rocked by a bomb in June 1926. The device probably consisted of sticks of gelignite placed inside a jam tin under a bed, and such was the explosion that it rocked a diggers’ camp kilometres away at the Boyes River.[5] Most likely it was not a big job to rebuild ‘The Boozer’ after that, since it would only have been a large paling hut, and soon, inevitably, it was the scene of further ruckuses, fist fights and raids by visiting police.

The most celebrated altercation at ‘The Boozer’ was the one in which digger Arthur Blacklow had the end of his nose bitten off in a drunken brawl, a case which played out as a grievous bodily harm charge in the New Norfolk Police Court. The alleged nose biter was acquitted after a piece of proboscis in a bottle was presented as evidence. Blacklow chose this time to reveal that he could not recognise his own nose:

‘He could not … say that the flesh in the bottle was the piece of nose he gave to the sister [Nurse Johnson, the Adamsfield bush nurse]. The piece given to the sister would be bigger.’[6]

Symmons and Langdon remained partners until 1930, when both left the field. Remarkably, neither was ever busted for selling liquor without a licence. ‘Remarkably’ refers in particular to a 1926 raid on the two buildings that sat on Lots 9 and 10. Sergeant Arnol entered the building on Lot 10, which appears to have been an alcohol warehouse, something akin to a Russian supermarket. Inside he found

- 26 bottles of brandy

- 30 half flasks of brandy and whisky

- 15 bottles of Schnapps

- 1 case of gin

- 1 case of brandy

- 8 bottles of gin

- 8 bottles of ‘special’ whisky

- 13 bottles of rum

- 50 flasks of gin and Schnapps

- 3 bottles of ale

- boxes consigned to R Langdon, Fitzgerald

Arnol charged John Holder, who was on the premises, with selling liquor without a licence, but he could not prove that Holder was the owner of the premises.

Sergeant Arnol also went next door to the building on Lot 9, where he found Ralph Langdon, plus a counter with 14 empty beer glasses on it, a bottle of gin, a bottle of rum, a 9-gallon cask of beer and other empty casks. He charged Langdon with selling liquor without a licence. However, because the premises were registered in the name of Bernie Symmons, the charge could not be sustained.[7] Failure to convict in the face of overwhelming evidence probably did nothing for Arnol’s career prospects.

Ralph Langdon’s story has other priceless elements. One is that when he sold his business in Adamsfield he got into an argument with the buyer, John Gladstone, and the sale of a sly-grog shop ended up being adjudicated on in the Supreme Court in 1931.[8] The second is that Langdon put his takings from his Adamsfield business into buying the lease of the Wheatsheaf Hotel in Hobart.[9] Did he wow the Licensing Board with ossie field testimonials?

Langdon’s successors in the Adamsfield sly-grog trade, John Gladstone and Elias Churchill, were both nabbed for selling liquor without a licence at ‘The Boozer’ in 1930.[10] Churchill followed Langdon by becoming a Hobart publican. In 1934 Langdon had the Wheatsheaf and Churchill had the Duke of York.[11] William Francis Powell, an old Victorian digger who had come to Adamsfield via Savage River, replaced them in the senior apprentice position at ‘The Boozer’. Powell’s sly-grog shop, which slowly disintegrated among the bracken ferns after his death in 1946, is still marked by an impressive bottle dump—last resting place of ‘The Miner’s Delight’, or the true ‘bank’ of Adamsfield.[12]

[1] ‘Hotel for Adams Field [sic]’, Mercury, 10 December 1925, p.10.

[2] ‘Successful police raid’, News (Hobart), 6 January 1925, p.3.

[3] ‘The “Ossy” field’, News, 5 November 1925, p.1

[4] ‘Whose property?’, Mercury, 1 December 1933, p.6.

[5] ‘Sensation at Adamsfield’, Mercury, 3 June 1926, p.6; ‘Adamsfield: the recent bombing case’, Mercury, 9 June 1926, p.9.

[6] ‘Adamsfield affray’, Mercury, 19 November 1931, p.2.

[7] ‘Alleged sly-grog selling’, Mercury, 8 January 1927, p.2. ‘Registered’ does not refer to holding a liquor licence. Under the various Crown Lands Acts, a residence licence could be obtained to take possession of and occupy up to a quarter of an acre of land.

[8] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 16 September 1931, p.11.

[9] ‘Whose property?’, Mercury, 1 December 1933, p.6.

[10] ‘Sly grog at Adamsfield’, Advocate (Burnie), 30 June 1930, p.5.

[11] ‘Licensing Courts’, Mercury, 29 October 1934, p.2.

[12] ‘Family notices’, Mercury, 9 March 1946, p.10.