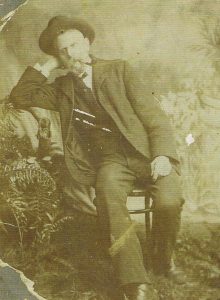

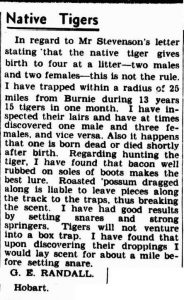

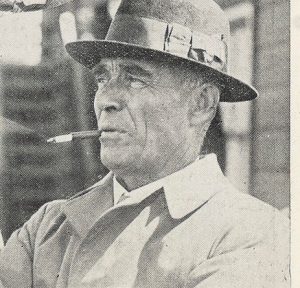

In 1945 one-time wrestler George Randall (1884–1963) recalled catching fifteen thylacines in the space of a month within 25 miles (40 km) of Burnie. He didn’t smother them in a bear hug. Randall reminisced that, upon finding tiger scats, he would lay a scent for half a mile from that point to his snares. The cologne no tiger could resist was actually the smell of bacon rubbed onto the soles of his boots.[1]

Fifteen tigers—a big boast indeed. I was suspicious of those numbers. Who was Randall, and if he was such an ace tiger killer why had he never claimed a government thylacine bounty? Government bounties of £1 for an adult tiger and 10 shillings for a juvenile were paid in the years 1888 to 1909, after all, plenty of time in which he could leave his mark. The production of a carcass at a police station was the basis for a bounty application.

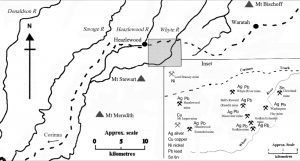

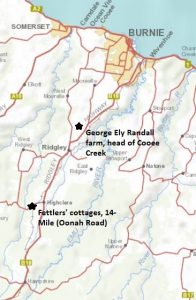

Randall was born at Burnie to George Ely Randall (1857–1907) and Emily Randall, née Charles (1871–1938).[2] By 1891 his father George Randall senior was a ganger maintaining the Emu Bay Railway (EBR) at Ridgley, south of Burnie. There were some tigers about, and it didn’t take much effort to find some Randalls killing one. In May 1892 Tom Whitton, who was aware of tigers coming about the gangers’ camp at night, set some snares and caught a large male. Two Randalls, George senior and his brother Charles, plus a fettler named Ted Powell, were at hand to help throttle the beast.

Wellington Times editor Harris added: ‘The tiger’s head was inspected by a large number of persons up to yesterday, many of whom remarked that they had never seen larger from a native animal; but yesterday the head had to be thrown away as it was manifesting signs of decay.’[3]

Thrown away?! So much for the £1 bounty. Perhaps the killers were too bloated on public admission fees to care about the bounty payment.

Another Randall killing came only two months later, when Powell and Charles Randall’s dogs flushed a tiger out of the bush at the 23-Mile on the EBR. Again the body was hauled into Burnie as a trophy.[4] Was a £1 government reward paid?

The government bounty records for the period May–July 1892 show the difficulty of reconciling newspaper reports with official records. There is no evidence of a bounty application having been made for the tiger killed on the EBR on 13 May 1892, but the one destroyed there in the week preceding 12 July 1892 is problematical. Was James Powell, who submitted a bounty application on 8 July, a relation of Ted Powell, the fettler involved in the two killings on the EBR? I could find no record of a James Powell working or residing in the Burnie area at that time, whereas two James Powells in pretty likely tiger-killing professions—manager of a highland grazing run, and bush farmer under the Great Western Tiers—were easily identified through digitised newspaper and genealogical records (see Table 1):

Table 1: Government thylacine bounty payments, May–July 1892, from Register of general accounts passed to the Treasury for payment, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

| Name | Identification | Application date | Number |

| G Atkinson | Probably farmer George Elisha Atkinson of Rosevears, West Tamar | 13 June 1892 | 2 adults[5] |

| A Berry | Probably shepherd Alfred James Berry, Great Lake, Central Plateau | 21 July 1892 | 1 adult[6] |

| John Cahill | Farmer/prospector, Stonehurst, Buckland, east coast | 8 July 1892 | 1 adult[7] |

| WF Calvert | Wool-grower/orchardist William Frederick Crace Calvert, Gala, Cranbrook, east coast | 21 July 1892 | 4 adults[8] |

| J Clifford | Probably bush farmer/hunter Joseph Clifford of Ansons Marsh, north-east | 12 May 1892 | 1 adult[9] |

| Harry Davis | Mine manager, Ben Lomond, eastern interior | 31 May 1892 | 2 adults & 1 juvenile[10] |

| CT Ford | Mixed farmer Charles Tasman Ford, Stanley, north-west coast | 21 July 1892 | 1 adult[11] |

| Thomas Freeman | Shepherd at Benham, Avoca, northern Midlands | 12 May 1892 | 1 adult[12] |

| E Hawkins | Shepherd William Edward Hawkins, Cranbrook, east coast | 9 July 1892 | 1 adult[13] |

| E Hawkins | Shepherd William Edward Hawkins, Cranbrook, east coast | 21 July 1892 | 1 adult[14] |

| Thomas Kaye | Labourer at Deddington, northern Midlands | 31 May 1892 | 1 adult[15] |

| John Marsh | John Richard James Marsh of Dee Bridge, Derwent Valley | 27 June 1892 | 1 adult & 1 juvenile[16] |

| W Moore junior | Bush farmer William Moore junior, Sprent, north-western interior | 13 June 1892 | 1 adult[17] |

| E Parker | Probably grazier Erskine James Rainy Parker of Parknook south of Cressy, northern Midlands | 27 June 1892 | 2 adults[18] |

| James Powell | Probably manager, Nags Head Estate, Lake Sorell, Central Plateau, or bush farmer, Blackwood Creek, northern Midlands | 8 July 1892 | 1 adult[19] |

| Charles Pyke | Mail contractor, Spring Vale, Cranbrook, east coast | 27 June 1892 | 1 adult[20] |

| A Stannard | Probably shepherd Alfred Thomas David Stannard, native of Mint Moor, Dee, Derwent Valley but thought to have been in the northern Midlands at this time | 21 July 1892 | 1 adult[21] |

| D Temple | Shepherd David Temple senior, Rocky Marsh, Ouse, Derwent Valley | 21 July 1892 | 1 adult[22] |

| R Thornbury | Farmer Roger Ernest Thornbury, Bicheno, east coast | 12 May 1892 | 1 adult[23] |

| H Towns | Farmer Henry Towns, Auburn, near Oatlands, southern Midlands | 20 June 1892 | 1 adult[24] |

The two EBR slayings are not the only known tiger killings missing from the bounty payment record: two young men reportedly snared a live tiger near Waratah at the beginning of May 1892, but the detained animal accidentally hanged itself on its chain in a blacksmith’s shop; while on 22 July 1892 well-known prospector/sometime postman and seaman Axel Tengdahl shot a tiger that broke a springer snare on the Mount Housetop tinfield.[25] (Another July 1892 killing by ‘Bill the Sailor’ Casey at Boomers Bottom, Connorville, Great Western Tiers, was not rewarded until 5 August 1892, a lag of almost a month.[26]) The reasons for the Waratah and Housetop killings going unrewarded are not clear. While Tengdahl was in an inconvenient place to submit a tiger carcass to a police station, he was probably also snaring for cash as well as meat, so would have needed to leave the bush anyway in order to sell his skins to a registered buyer.

Anyway, back to Randall the tiger tamer. We know that young George Randall junior, eight years old in 1892, grew up with his elders hunting and chasing tigers. Then he went out on his own. He claimed that he trapped within a 40-km radius of Burnie for thirteen years, and that sometime during that period, in the space of a month, he killed fifteen tigers. It should be easy enough to figure out when this was. The ten-year-old would have been still living along the EBR with his family and presumably at school in 1894 when his mother was judged to be of unsound mind and committed to the New Norfolk Asylum.[27] In the years 1897–1901 (from the age of thirteen to seventeen) he was an apprentice blacksmith while living with his father at the 14-Mile (Oonah).[28] [29] He was still in the Burnie area in 1902 when he was cutting wood for James Smillie and driving a float for JW Smithies, but in 1903, as a nineteen-year-old, he was an insolvent fettler at Rouses Camp near Waratah.[30]

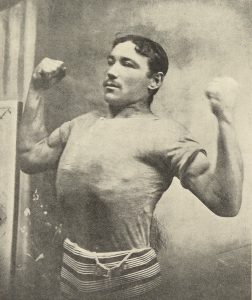

By 1907 Randall was a married man working at Dundas.[31] He did not return to the Burnie region after that, doing the rounds of Tasmania’s mining fields and rural districts for two decades with intermissions at Devonport, Hobart and Hokitika, the little mining port on the west coast of New Zealand’s South Island.[32] At Zeehan he was described as ‘the champion [wrestler] of Tasmania’, and he was noted not as a hunter but as a weightlifter and athlete.[33] More importantly, the blacksmith qualified as an engine driver and a winding engine driver, making him eminently employable in resource industries.[34] Randall finally settled at Hobart in 1929 at the age of 45.[35]

If we consider his Rouses Camp fettling a short aberration, the thirteen-year period in which Randall hunted around Burnie could have been approximately 1894 to 1906, that is, between the ages of ten and 22. The government bounty was available for the whole of this time, so why is there no record of George Randall’s prowess as a tiger tamer?

There are two possibilities. One is that Randall, a born showman, simply lied. The other possibility is that he killed or captured (he doesn’t say which) a lot of tigers but the evidence of same is hard to find.[36] There are few surviving records of the sale of live thylacines to zoos or animal dealers, or of bounty applications made through an intermediary like a hawker or shopkeeper. In some cases suspicion of acting as an intermediary even attaches to farmers—such as Charles Tasman (CT) Ford.

Randall may have been rewarded for fifteen thylacine carcasses through intermediaries such as shopkeepers, hawkers, skin buyers or some regular traveller to Burnie. Hunter/skin buyers such as Thomas Allen (15 adults and a juvenile, 1899–03)[40] and Edward Brown (7 adults, 1904–05)[41] operated in the Ridgley-Guildford area along the railway line, possibly accounting for some bounty payments for the likes of Randall, ‘Black Harry’ Williams, ‘Five-fingered Tom’ Jeffries and Bill Todd.

However, it does seem extraordinary that fifteen tiger captures or kills within the space of a month escaped public attention. We can assume that Randall never anticipated the scrutiny of his life that digitisation of records now allows us, let alone that someone who read his 1945 letter in the next century would try to dissect his life in order to verify his words. It is likely that Randall guessed that he had hunted in the Burnie region for thirteen years. Perhaps it was ten years, and perhaps his tigers took a lot longer to secure. Perhaps in a trunk in an attic somewhere is a mouldering trophy photo of the wrestler who wrangled tigers—dead or alive.

[1] GE Randall, ‘Native tigers’, Mercury, 12 December 1945, p.3.

[2] Born 1 July 1884, birth record no.1298/1884, registered at Emu Bay; died 14 July 1963, will no.44135, AD960/1/95, p.911 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall#, accessed 28 March 2020.

[3] ‘Capture of a native tiger’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 12 May 1892, p.2.

[4] ‘A big tiger’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 12 July 1892, p.2.

[5] Bounty no.147, 13 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[6] Bounty no.207, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[7] Bounty no.190, 8 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[8] Bounty no.203, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[9] Bounty no.118, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[10] Bounty no.136, 31 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[11] Bounty no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] Bounty no.119, 12 May 1892; LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[13] Bounty no.188, 9 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[14] Bounty no.210, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[15] Bounty no.135, 31 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[16] Bounty no.173, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[17] Bounty no.148, 13 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[18] Bounty no.172, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[19] Bounty no.189, 8 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[20] Bounty no.171, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[21] Bounty no.206, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Bounty no.208, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[23] Bounty no.117, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[24] Bounty no.151, 20 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[25] ‘Waratah notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 10 May 1892, p.3; ‘Housetop notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 28 July 1892, p.2.

[26] ‘Longford notes’, Launceston Examiner, 14 July 1892, p.2; bounty no.236, 5 August 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[27] ‘Burnie: Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 7 February 1894, p.1.

[28] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 July 1901, p.3.

[29] ‘For sale’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 31 January 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Arson: case at Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 20 March 1902, p.3; ‘New insolvent’, Examiner, 29 April 1903, p.4.

[31] He married Ethel May Jones on 22 May 1907 at North Hobart (‘Silver wedding’, Mercury, 23 May 1932, p.1). Dundas: ‘To-night at the Gaiety’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 7 September 1907, p.3.

[32] Zeehan: Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 August 1908, p.2; ‘Macquarie district’, Police Gazette Tasmania, vol.48, no.2595, 16 April 1909, p.81; Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Darwin, Subdivision of Zeehan, 1914, p.2. Devonport: Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Devonport, 1914, p.36. Waratah: ‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 17 October 1918, p.2; Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Darwin, Subdivision of Waratah, 1919, p.14. Hobart: Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Denison, Subdivision of Hobart East, 1922, p.30. Mathinna: ‘Personal’, Daily Telegraph, 30 September 1924, p.5. Cygnet: ‘Shooting at electric lines’, Mercury, 28 June 1926, p.4. Taranna: ‘Centralisation of school teaching’, Mercury, 12 May 1927, p.6. Hokitika: ‘Macquarie district’.

[33] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 August 1908, p.2; ‘Macquarie district’.

[34] Certificate of competency as second class engine drive, 1916, AA80/1/1, p.424, image 63 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall; Certificate of competency as mining engine driver, 1926, LID24/1/4, pp.109 and 109b (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall#, accessed 28 March 2020.

[35] ‘Motor cycle registrations’, Police Gazette Tasmania, vol.68, no.3629, 8 February 1929, p.33.

[36] Randall mentioned using springers, the supple saplings used to ‘spring’ the snare, generally employed in footer snares, which caught the animal by the paw, not being designed to kill it. Many thylacines sent to zoos were captured in footer snares.

[37] Bounties no.365, 31 July 1891 (2 adults); no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.402, 9 January 1893; no.71, 27 April 1893 (2 adults); no.91, 5 May 1893; no.125, 19 June 1893; no.183, 24 July 1893, no.4, 23 January 1894 (2 adults); no.239, 22 September 1897 (3 adults, ‘August 2’); no.276, 4 November 1897 (2 adults, ’27 October’); no.379, 1 February 1898 (‘4 December’); no.191, 2 August 1898 (2 adults, ‘7 July’); no.158, 30 May 1899 (’26 May’); no.253, 30 August 1899 (3 adults, ’24 August’); no.254, 30 August 1899 (2 juveniles, ‘24 August’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[38] Bounties no.43, 27 February 1900 (3 adults, ’22 February’); no.250, 16 August 1900 (5 adults, ’26 July’); no.316, 3 October 1900 (4 adults, ’27 September’); no.398, 15 November 1900 (4 adults and 4 juveniles, ’28 October’); no.79, 13 March 1901 (2 adults, ’28 February’); no.340, 31 July 1901 (7 adults, ’25 July’); no.393, 28 August 1901 (6 adults, ‘2/3 August’); no.448, 3 October 1901 (’26 September’); no.509, 5 November 1901 (’24 October 1901’); no.218, 7 May 1903 (2 adults, ’24 April’); no.724, 17 November 1903 (4 adults); no.581, 21 June 1906, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[39] Woolnorth farm journals, VDL277/1/1–33 (TAHO). The Woolnorth figure for 1900–06 excludes one adult and one juvenile killed by Ernest Warde and for which he claimed the government bounty payment himself (bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, LSD247/1/2 [TAHO]).

[40] Bounty no.374, 12 January 1899 (3 adults, ‘3 December’); no.401, 15 November 1900 (3 adults, ’15 June’); no.482, 21 January 1901 (3 adults, ’17 December’); no.22, 4 February 1901 (3 adults, ‘4 January’); no.985, 25 July 1902 (‘July’); no.1057, 27 August 1902 (’15 August’); no.1091, 17 September 1902 (‘4 September 1902’); no.462, 6 August 1903, (1 juvenile, ’24 July’), LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO). See ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 15 December 1900, p.2.

[41] Bounty no.233, 16 June 1904 (5 adults); no.125, 28 September 1905 (2 adults, ’31 August and 8 September’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).