by Nic Haygarth | 23/05/25 | Story of the thylacine

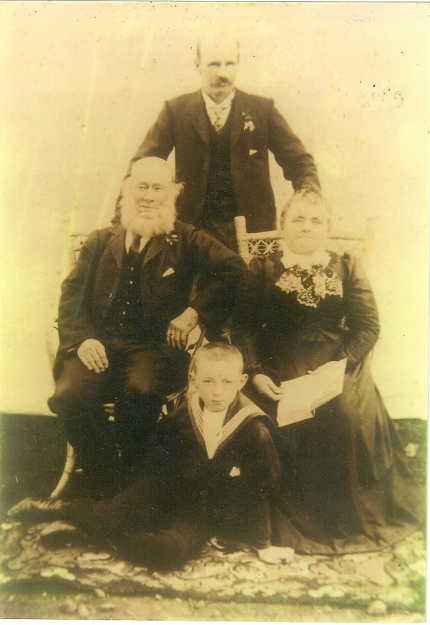

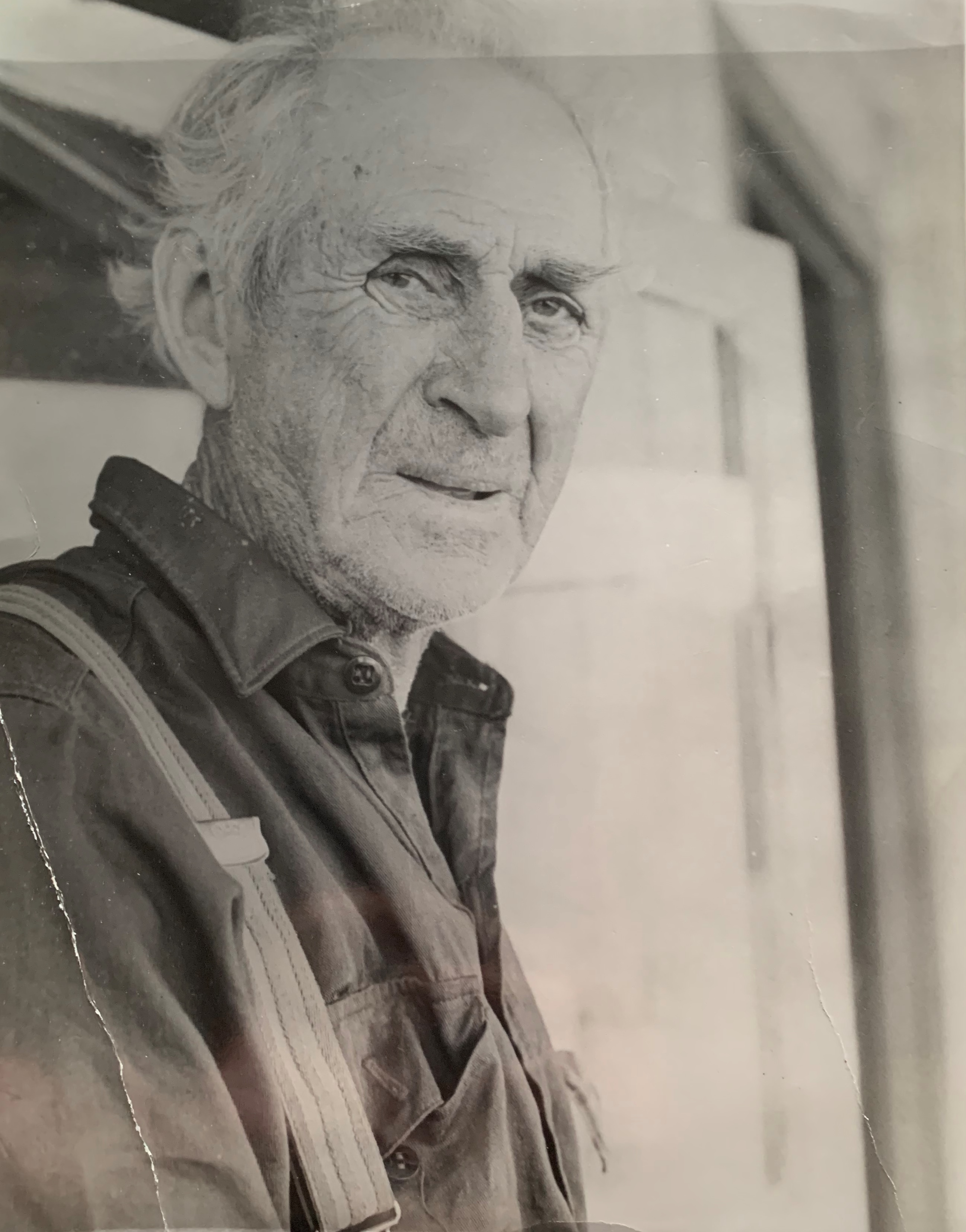

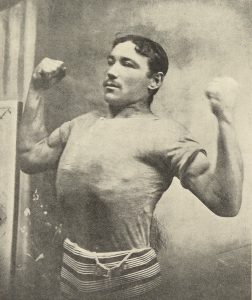

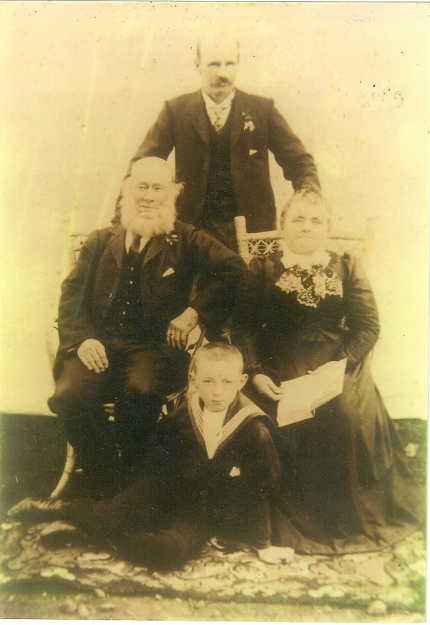

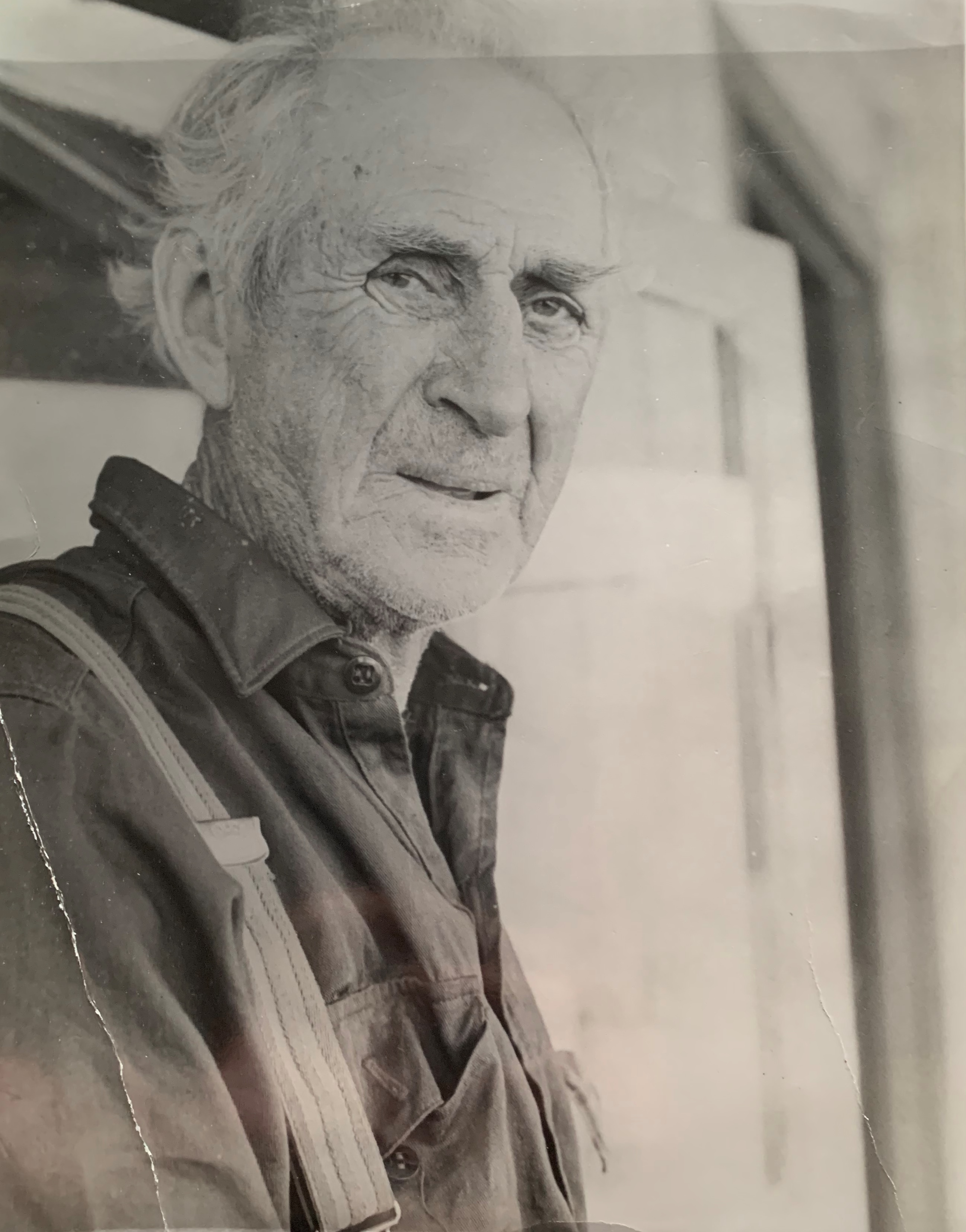

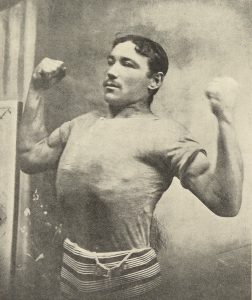

James ‘Tiger’ Harrison, Wynyard native animals dealer, snarer, prospector, track cutter, estate agent, shipping agent, Christian Brethren registrar, tourist chauffeur, human ‘cork’ and Crown bailiff of fossils. Photo from the Norman Larid files, NS1143, Tasmanian Archives (TA).

In the mid-1920s thylacines were still reported by bushmen in remote parts of the north-west. Luke Etchell claimed there was a time when he caught six or seven ‘native tigers’ per season at the Surrey Hills.[1] Like Brown brothers at Guildford, Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) hands at Woolnorth were still doing a trade in live native animals—although the latter property was out of tigers. On 7 July 1925 Hobart City Council paid the VDL Co £60 10 shillings for what can only be described as two loads of ‘animals’—presumably Tasmanian devils and quolls—recorded as being carted out to the nearest post office at Montagu during the previous month.[2] A further transaction of £30 was recorded in October 1925, when it is possible Woolnorth manager George Wainwright junior hand delivered a crate of live native animals to Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo.[3]

James ‘Tiger’ Harrison (1860–1943) of Wynyard took his animals dead or alive. He bought and sold living Tasmanian birds and marsupials, including tigers, but also hunted for furs in winter. In July 1926 Harrison and his Wynyard friend George Easton (1864–1951) secured government funding of £2 per week each to prospect south of the Arthur River for eight weeks.[4] However, their main game was hunting: the two-month season opened on 1 July 1926.

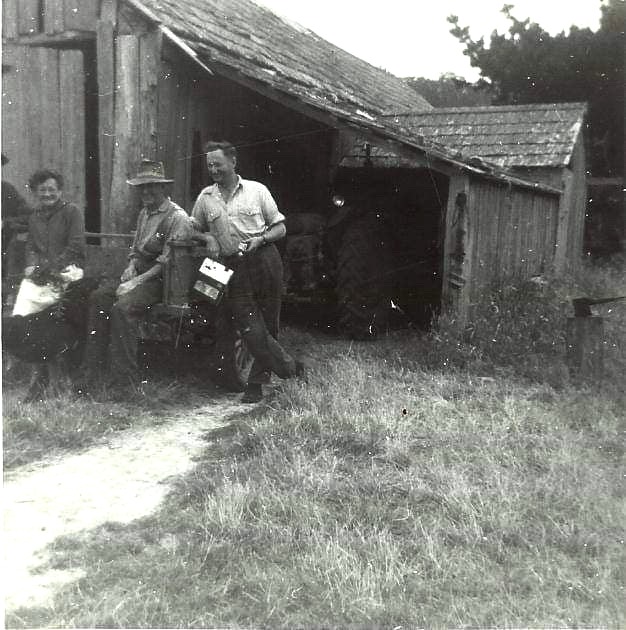

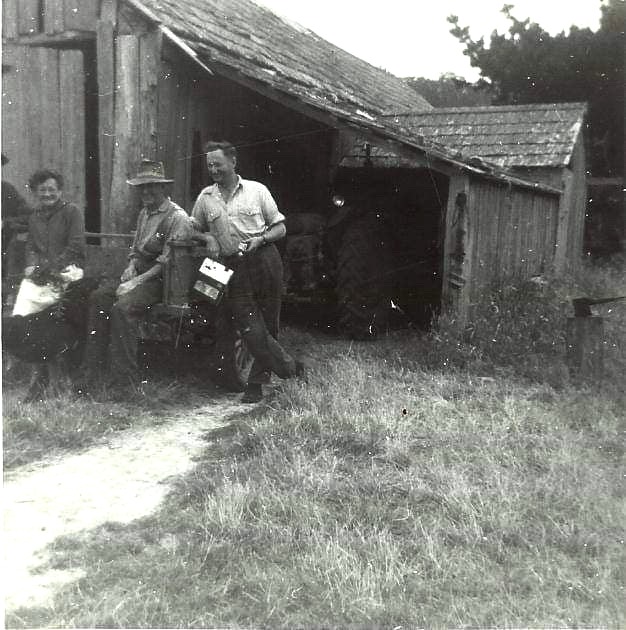

James Harrison’s collaborators George Easton and George Smith with a bark boat used to rescue Easton at the Arthur River in 1929. Photo courtesy of Libby Mercer.

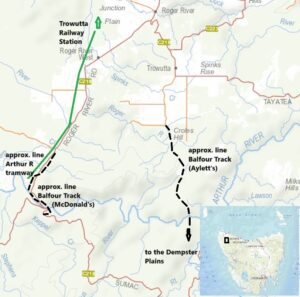

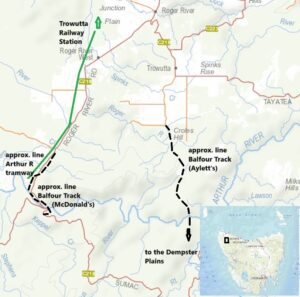

TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST©STATE OF TASMANIA

Easton, an experienced bushman in his own right, made snares most evenings until the pair departed Wynyard on 14 July.[5] At Trowutta Station they boarded the horse-drawn, wooden-railed tram to the Arthur River that jointly served Lee’s and McKay’s Sawmills.[6] Next day, Arthur Armstrong from Trowutta arrived with a pack-horse bearing their stores, and the pair set out along the northern bank of the Arthur towards the old government-built hut on Aylett’s track.[7] However, on a walk to the Dempster Plains to shoot some wallaby to feed their dogs, Harrison injured his knee so badly that he couldn’t carry a pack. So before they had even set some snares the pair was forced to return home.[8] On their slow, rain-soaked journey they sold their stores to the Arthur River Sawmill boarding-house keeper Hayes—the only problem being delivery of said stores from their position up river.[9] While Harrison went home by horse tram and car, Easton had to help Armstrong the packer retrieve the stores.[10]

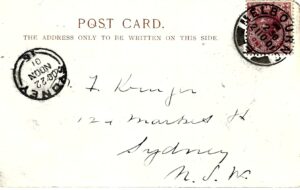

Martha Crole and her daughters. From the Weekly Courier, 10 April 1919, p.22.

The Crole house at Trowutta. From the Weekly Courier, 10 April 1919, p.22.

‘Tiger country’ around the Arthur River

If not for the injury Harrison may have secured more than furs over the Arthur. One of the European pioneers in that area was grazier Fred Dempster (1863–1946), who appears to have rediscovered pastures celebrated by John Helder Wedge in 1828.[11] Out on his run in 1915 Dempster met a breakfast gatecrasher with cold steel. The elderly tiger reportedly measured 7 feet from nose to tail and being something of a gourmet registered 224 lbs on Dempster’s bathroom scales.[12] In dramatising this shooting, anonymous newspaper correspondent ‘Agricola’ mixed familiar thylacine attributes with the fanciful idea of its ferocity:

This part is the home of the true Tasmanian tiger … This animal must not be confounded with the smaller cat-headed species [he perhaps means the ‘tiger cat’, that is, spotted-tailed quoll, Dasyurus maculatus] so prevalent beyond Waratah, Henrietta and other places. The true species is absolutely fearless in man’s presence, and if he smells meat will follow the wayfarer on the lonely bush tracks for miles, stopping when he does and going on when he resumes his walk. It has been proved beyond question that these brutes will not shift off the paths when met by man, and they will always attack when cornered.[13]

One mainland newspaper was apparently so confused by ‘Agricola’s’ account that he called Dempster’s thylacine ‘a huge tiger cat’.[14]

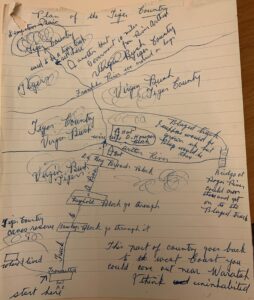

Trowutta people had no problem distinguishing quoll from tiger. They caught the latter unwittingly while snaring. Fred and Martha Crole and family of Trowutta made hundreds of snares on a sewing machine, eating the wallaby meat and selling the skins they caught. One of their boys, Arthur Crole (1895–1972), landed a tiger alive in a snare, killed it, tanned the hide and used it as a bedside rug.[15] While south of the Arthur, Harrison and Easton were unlucky not to run into Trowutta farmers Fred and Violet Purdy, who caught a tiger in a footer snare there during the 1926 season. When the Purdys approached the captured animal it broke the snare and disappeared. However, tigers also frequently visited their hut south of the river at night and they saw their footprints in the mud next morning.[16] Violet Purdy claimed to have spent six months straight living in the ‘wild bush’ (the hunting season in 1926 was only July and August), and her observations of the thylacine suggest someone with at least second-hand knowledge. Like ‘Agricola’, she knew of the tiger’s reputed habit of refusing to move off a track to let a human pass. Unlike him, she attested to the animal’s shyness. Purdy recommended ‘a couple of good cattle dogs’ as the means of tracking it down. She and her husband found thylacine tracks at the Frankland River as they crossed it to reach the Dempster Plains.[17] Decades later Purdy regaled the Animals’ and Birds’ Protection Board with her tales, illustrating them with a map of ‘tiger country’ between Trowutta and the Dempster Plains.

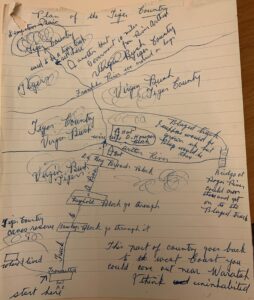

‘Tiger country’ between Trowutta and Dempster Plains, as it looked in 1926, according to Mrs V Kenevan,

formerly Violet Purdy of Trowutta. From AA612/1/59 (TA).

Snaring at Woolnorth

By the time Easton got home to Wynyard, Harrison, apparently recovered from his knee injury, had arranged for them both to snare at Woolnorth, where no swags needed to be carried, since stores were supplied. The VDL Co employed hunters every season to kill ‘game’, this serving the dual purpose of saving the grass for the stock and bringing the company income at a time of low agricultural prices. At this time hunters paid a royalty of one in six skins to the company.

Easton’s diary entries give rare insight into a hunting engagement. Harrison and Easton took the train to Smithton and caught the mail truck to Montagu, from which they were borne by chaise cart to the Woolnorth homestead. That night the snarers were put in a cottage generally reserved for the VDL Co agent, AK McGaw.[18] Next day station manager George Wainwright junior showed them their lodgings (tents next to a lagoon which served as the water supply) and how snaring (using springer snares but also neck snares along fences) and skinning were done at Woolnorth. Wainwright, an old hand, claimed to be able to skin 30 animals per hour.[19] Storms, horse leeches, which had a way of attaching themselves to the human scalp, and cutting springers and pegs kept the snarers very well occupied between snare inspections, an 11-km-long daily routine. The game was nearly all wallaby and ringtails, and Harrison and Easton dried their skins not in a skin shed but by hanging them in trees.[20] Bathing meant a sponge bath with a prospecting dish full of cold water—which also constituted the laundry facilities.[21] The last day of the season at Woolnorth was traditionally an all-in animal shoot, after which the season’s skins were baled, treated with an arsenic solution to kill insects and delivered to a skins dealer.[22] In the two-month 1926 season the VDL Co made £493 from the fur industry, a big reduction on the previous year (£1296) when the season had lasted three months.[23]

However, Harrison didn’t last the distance, calling it quits on 13 August after barely two weeks, leaving Easton to carry on alone until the season ended eighteen days later. Their skin tally at 13 August stood at 16½ dozen—198 skins or 99 apiece.[24]

Returning to ‘tiger country’

Once again ‘Tiger’ Harrison was in the wrong place at the wrong time to live up to his nickname. While he was working at tiger-free Woolnorth, timber worker, hunter and sometime miner Alf Forward snared two tigers, one alive, one choked to death by a stiff spring in a necker snare at the Salmon River Sawmill south of Smithton.[25] Forward is said to have exhibited the living one in Smithton before selling it to Harrison.[26] He almost had another live one in the following month, when a tiger detained by Forward’s snare for two days bit his capturer’s hand, thereby effecting its escape.[27]

Harrison eventually decided to cut out the middle-man. From 1927 he conducted expeditions specifically to obtain living thylacines to sell. He had no luck until in June 1929 he caught one 3 km south-west of Takone.[28] The Arthur River catchment remained ‘tiger country’ in the mid-1930s when ‘Pax’ (Michael Finnerty) and Roy Marthick claimed to have seen them while prospecting.[29] The question of whether they are there today still entertains Tarkine tourists and the worldwide thylacine mafia.

[1] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (Tasmanian Archives, henceforth TA).

[2 Payment recorded 7 July 1925. On 9 June 1925: ‘W Simpson taken animals to Montagu’; 22 June 1925: ‘W Simpson went to Montagu with load of animals’, Woolnorth farm diary, VDL277/1/53 (TA).

[3] Payment recorded on 13 October 1925. On 4 October 1925 George Wainwright junior and his wife departed Woolnorth for the Launceston Agricultural Show (Woolnorth farm diary VDL277/1/53). It is possible that he took a crate of animals on the train to Hobart.

[4] GW Easton diary, 1 July 1926 (held by Libby Mercer, Hobart).

[5] GW Easton diary, 1–14 July 1926.

[6] GW Easton diary, 15 July 1926.

[7] GW Easton diary, 16 July 1926.

[8] GW Easton diary, 18 July 1926.

[9] GW Easton diary, 23 July 1926.

[10] GW Easton diary, 25 and 26 July 1926.

[11] JH Wedge, ‘Official report of journeys made by JH Wedge, Esq, Assistant Surveyor, in the North-West Portion of Van Diemen’s Land, in the early part of the year 1828’, reprinted in Venturing westward: accounts of pioneering exploration in northern and western Tasmania by Messrs Gould, Gunn, Hellyer, Frodsham, Counsel and Sprent [and Wedge], Government Printer, Hobart, 1987, p.38.

[12] See for example ‘Boat Harbour’, North West Post, 22 February 1915, p.2. Dempster probably didn’t have any bathroom scales with him. Rather mysteriously, the author of ‘A huge tiger cat’, Westralian Worker, 19 March 1915, p.6, put the animal’s weight as ‘2 cwt’ (224 lbs).

[13] ‘Agricola’, ‘Farm jottings’, North West Post, 24 February 1915, p.4. In another column ‘Agricola’ claimed with equal dubiousness that under Mount Pearse trappers caught tigers in pits, and that if more than one tiger was collected in the same pit at the same time the captured animals would fight to the death. See ‘Agricola’, ‘Farm jottings’, North West Post, 10 July 1914, p.4.

[14] ‘A huge tiger cat’, Westralian Worker, 19 March 1915, p.6.

[15] Fred and Graham Crole, in Women’s stories: different stories—different lives—different experiences: a Circular Head oral history project (compiled and edited by Pat Brown and Helene Williamson), Forest, Tas, 2009, p.192.

[16] The hut was on Aylett’s Track to Balfour.

[17] Violet Kenevan, Kingswood, New South Wales, to secretary of the Animals’ and Birds’ Protection Board, 30 October 1956, AA612/1/59 (TA).

[18 GW Easton diary, 27 July 1926.

[19] GW Easton diary, 30 July 1926.

[20] GW Easton diary, 18 August 1926.

[21] GW Easton diary, 15 August 1926.

[22] GW Easton diary, 31 August and 6–9 September 1926; Woolnorth farm diary, 31 August 1926, VDL277/1/54 (TA).

[23] The figures are from VDL129/1/7 (TA).

[24] GW Easton diary, 13 August 1926.

[25] ‘Hyena choked in snare at Salmon River’, Circular Head Chronicle, 11 August 1926, p.5.

[26] ‘TT, from New Town’, ‘Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 24 August 1954, p.4, claimed that Alf Forward caught the animal in a kangaroo snare at the Salmon River ‘less than 30 years ago’ and sold it to Harrison after putting it on show in Smithton.

[27] ‘Hand bitten by a hyena’, Circular Head Chronicle, 29 September 1926, p.5.

[28 GW Easton diary, 17 June 1929; Circular Head Chronicle, 29 May 1929.

[29] See ‘Pax’ (Michael Finnerty), ‘A “bush-whacker’s” experience in the north-west’, Mercury, 6 May 1937, p.8; Roy Marthick to the Fauna Board, 10 February 1937 (TA); Roy Marthick quoted by Charles Barrett, ‘Out in the open: nature study for the schools’, Weekly Times (Melbourne), 10 July 1937, p.44.

by Nic Haygarth | 10/08/24 | Story of the thylacine

At Pisa Cemetery the Parkers, O’Connors, Gatenbys and Smiths are all equals. Some of course are more equal than others, having large, decorated headstones and obelisks, but their bones moulder in the same clay and their spirits, should they have any, mingle on the same windswept plain rolling back to the blue profile of the Great Western Tiers. It is remarkable that the graves of John (c1822–1903) and Hannah Jane Smith (c1819–1903) are marked at all. It doesn’t get more anonymous than being John Smith, and the anonymity of a bare patch between the plinths of their betters awaited most of the likes of these two. Perhaps their old employer Roderic O’Connor (1849–1908) gave them a monument as a mark of respect.

Pisa (St Mark’s Anglican, Lake River) Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

The irony of that action wouldn’t have been lost on John Smith, one of 314 bearers of that name conscripted to Van Diemen’s Land. A native of Nottingham, Jack was a single, semi-literate, 170-cm-tall labourer when sentenced to 7 years’ transportation for stealing a pair of shoes and a hatchet as a 20-year-old in 1842. The hatchet was a token of a combative life. He had a prior conviction and five short prison terms under his belt, being, apparently, ‘a bad irreclaimable lad, connected to other lads who live by plunder’. Transported on the Forfarshire, he appears to have laboured in a probation gang at Westbury before his attempts to abscond landed him in the Port Arthur Gaol. Jack spent 3½ years in the probation system, enduring 179 lashes, 88 days of solitary confinement and 21 months of hard labour in chains before being released for private service in 1847 at the age of about 25. What would his opinion have been at that time about whether transportation was a sentence or an opportunity?

The monument marking the graves of John and Hannah Jane Smith, Pisa Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photos.

Jack then worked for Edward Archer of Northbury, Longford (nearly two years), and Joseph Oakley of Oatlands, achieving freedom by servitude at the expiry of his sentence in 1849.[1]

Perhaps he still brandished that hatchet, because within a few years Jack was living by plunder once more, working out of a hide-out near Millers Bluff. Known as ‘Jack the Hunter’, in the mould of the Irish outlaw ‘Jack the Shepherd’, he was accused of rustling sheep from the large properties adjoining the slopes of the Great Western Tiers. In 1856 graziers Arthur O’Connor of Connorville and Charles Parker of Parknook tracked him down and sent a volley his way. Jack raised his weapon at O’Connor but it failed to discharge, and he made his escape.[2] The threat Jack posed to wool-growing was raised in parliament.[3] An armed police party sent to apprehend him mistakenly pounced on a roving entomologist at the Hummocky Hills.[4] A posse led by District Constable Thomas Kidd of George Town did better, finally arresting Jack the Hunter or ‘Hellfire Jack’[5] at Hells Bottom on the slopes of Millers Bluff in 1858. Here they also found the evidence of his ovine crimes in a veritable maze of hideouts, including an underground wool store. Jack was shot in the arm while trying to escape, newspaper reports varying in their accounts of his injuries.[6] His victims, the Gatenbys and O’Connors, secured two of his hunting dogs as a form of recompense.[7] The ex-convict was sentenced to four years’ gaol for stealing 15 sheep worth £8 from George Gatenby of Barton.[8]

In 1870 a newspaper writer recounting Jack’s tale commented that ‘Poor Jack, now in confinement, must look back with harrowing regret to his wild hut high on the tier’.[9] In fact Jack was already back on the tier.[10] Somehow Arthur O’Connor had forgiven his depredations and allowed him back onto Connorville—presumably as a shepherd! After all, there’s no substitute for local knowledge. Jack’s residence was Boomers Bottom, a sheep run where the Lake River cut a passage down through the mountains. Adam Jackson’s 1847 survey of the upper Lake River didn’t recognise Hells Bottom but mapped Scrubby Den and the even more tantalising Tigers Bottom.

Adam Jackson’s 1847 survey of the upper Lake River where there be tigers. Copyright State of Tasmania.

Jack was certainly at Connorville in 1885 when ‘Jimmy the Sailor’ Casey saved his five-year-old from drowning in the mill race.[11] But Jack was more than a father and a hunter: he was a serial thylacine decapitator. He buried his hatchet in tigers’ necks. The submission of severed animal heads to unsuspecting public officials sounds like something out of The Godfather.[12] However, this seems to have been acceptable behaviour at the time. At least twelve thylacine heads were presented to the Longford warden or police office for payment in the years 1888–97, Connorville and Parknook being star killing fields.[13] Jack produced eight of these, probably securing them in necker snares.[14] In 1897 he claimed to have killed about 130 tigers during 30 years’ residence at Boomers Bottom.[15] It is possible that Jack managed a line of necker snares across a gully through which tigers were thought to be entering the Connorville property, in the fashion of the Woolnorth ‘tigerman’ at Green Point in the far north-west. Even so, four tigers per year hardly constitutes an invasion, and we do not know if any of those 130 savaged any of Connorville’s 14,000-strong grazing flock.[16]

Jack’s partner Hannah Jane Smith predeceased him by nine months.[17] Her story, like those of so many other anonymous wives and female partners, is unknown. Their child or children are also untraceable, their births seemingly evading the registrar. Perhaps Hannah helped Jack secure his sixteen £1 government tiger bounties.[18] That would have paid for some sugar, tea, tobacco and snaring hemp or wire but not saved them from kangaroo leather ensembles and a diet of macropod and potato. Perhaps Jack’s hunting was a lot more lucrative than that in the backblocks of Connorville. Perhaps Jack and Hannah lived at a distance in mutual contempt. We will never know. They keep their secrets beneath the loam at St Mark’s, Lake River, where the tigers once roamed.

[1] Conduct record for John Smith per Forfarshire, CON33/1/44, p.197 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA), https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON33-1-44/CON33-1-44p197; Conduct record for John Smith per Forfarshire, CON37/1/9, image 216 (TA), https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON37-1-9, both accessed 4 August 2024.

[2] ‘Bushranging’, Launceston Examiner, 18 September 1856, p.3.

[3] ‘House of Assembly—last night’, Courier, 9 October 1858, p.2.

[4] ‘An Old Vet’, ‘Jack the Hunter: an episode in a VDL policeman’s life’, Daily Telegraph, 4 January 1895, p.6.

[5] ‘Capture of another bushranger’, Courier, 8 October 1858, p.3. ‘Hellfire Jack’ was also the nickname of the ex-convict John Snelson.

[6] ‘Bushranging in Tasmania’, Courier, 8 October 1858, p.3.

[7] George Gatenby diary, 31 August and 1 September 1858, NS1255/1/1 (TA).

[8] ‘Oatlands Supreme Court’, Hobart Town Advertiser, 3 January 1859, p.7.

[9] ‘Aegles’, ‘Notes in north Tasmania’, Launceston Examiner, 15 February 1870, p.5 (reprinted from the Leader [Melbourne]).

[10] ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[11] ‘Cressy’, Mercury, 22 September 1885, p.4.

[12] The Godfather, a 1972 movie directed by Francis Ford Coppola, included a scene in which a severed horse’s head was placed in the bed of a sleeping man.

[13] Longford notes’, Launceston Examiner, 2 August 1888, p.5; ‘Longford notes’, Launceeston Examiner, 2 July 1889, p.4; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 13 March 1890, p.3; ‘Longford’, Mercury, 4 October 1890, p.2; ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 30 September 1891, p.2; ‘Country intelligence’, Tasmanian, 27 August 1892, p.30; ‘Longford’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1893, p.2; ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[14] ‘Longford’, Launceston Examiner, 13 March 1890, p.3; ‘Longford notes’, Tasmanian, 4 October 1890, p.22; ‘Country intelligence’, Tasmanian, 27 August 1892, p.30; ‘Longford’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1893, p.22;

[15] ‘Longford Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 February 1897, p.5.

[16] The size of the sheep flock is from E Richall Richardson, ‘A tour through Tasmania (letter no.73): Connorville’, Tribune, 12 November 1877, p.2.

[17] Headstone, Pisa Cemetery.

[18] Bounties no.582, 17 December 1889; no.81, 18 March 1890; no.354, 20 August 1890; no.463, 7 October 1890; no.62, 26 March 1891; no.184, 22 May 1891; no.822, 1 April 1892; no.272, 12 September 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.123, 19 June 1893 (2 adults); no.13, 5 March 1895; no.37, 30 [sic] February 1896; no.39, 5 March 1897 (3 adults); no.45, 17 March 1898 (‘2 March’), LSD247/1/2 (TA).

by Nic Haygarth | 26/09/21 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

Stephen Spurling III (1876–1962) rode the rails and marched the mountains in his quest to snap Tasmania. Revelling in ‘bad’ weather and ‘mysterious’ light, this master photographer shot the island’s heights in Romantic splendour. His long exposures of the lower Gordon River are likely to have helped shape the reservation of its banks in 1908.[1] Snow-shoed, ear-flapped and roped to a tree, he captured Devils Gullet in winter and froze the waters of Parsons Falls. But Spurling wanted to record the full gamut of life. He was there when the whales beached, the bullock teams heaved, the apple packers boxed antipodean gold and floodwaters smashed the Duck Reach Power Station. His lens was ever ready.

Stephen Spurling III in 1913, photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Oddly, just about the only thing Spurling didn’t snap was a sack full of thylacine heads which he claimed to have seen at the Stanley Police Station in 1902. Forty-one years after the event, Spurling wrote that he watched ‘cattlemen from a station almost on the W coast [produce] two sacks of tigers’ heads (about 20 in number) and [receive] their reward’.[2] One-hundred-and-nineteen years after the event, this claim is hard to reconcile with the records of the government thylacine bounty. It adds a puzzle to the story of the so-called Woolnorth tigermen.

The Woolnorth tigermen

About 170 thylacines were killed at the Van Diemen’s Land (VDL Co) property of Woolnorth in the years 1871–1912, mostly by the company’s tigermen—a lurid title given to the Mount Cameron West stockmen. The tigermen had a standard job description for stockmen, receiving a low wage for looking after the stock, repairing fences, burning off the runs and helping to muster the sheep and cattle. They supplemented their income by hunting kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons, ringtail and brush possums. The only departure from the normal shepherd’s duty statement was keeping a line of snares across a neck of land at Green Point—now farming land at Marrawah—where the supposedly sheep-killing thylacines were thought to enter Woolnorth. The VDL Co paid their employees a bounty of 10 shillings for a dead thylacine, which was changed to match the government thylacine bounty of £1 for an adult and 10 shillings for a juvenile introduced in 1888. To make a government bounty application the tiger killer needed to present the skin at a police station, although sometimes thylacine heads sufficed for the whole skin.

It is not easy to work out how or even whether the Woolnorth tigermen generally collected the government thylacine bounty in addition to the VDL Co bounty. It is reasonable to think that the VDL Co would have encouraged its workers to do this, since doubling the payment doubled the incentive to kill the animal on Woolnorth. However, only two men are recorded as receiving a government thylacine bounty while acting as tigerman, Arthur Nicholls (6 adults, in 1889) and Ernest Warde (1 adult, 1 juvenile, in 1904).[3] This suggests that if Woolnorth tigermen and other staff received government thylacine bounties they did so through an intermediary who fronted up at the police station on their behalf.

Charles Tasman Ford and family, PH30/1/6928 (Tasmanian Archives Office).

Charles Tasman Ford and William Bennett Collins

The most likely candidates for the job of Woolnorth proxy during the government bounty period 1888–1909 were CT (Charles Tasman) Ford and WB (William Bennett) Collins. In the years 1891–99 Ford, a mixed farmer (sheep cattle, pigs, poultry, potatoes, corn, barley, oats) based at Norwood, Forest, near Stanley, claimed 25 bounties (23 adults and 2 juveniles), placing him in the government tiger killer top ten.[4] If you include bounty payments that appear to have been wrongly recorded as CJ Ford (5 adults, 1896) and CF Ford (1 adult, 1897), his tally climbs to an even more impressive 29 adults and 2 juveniles—lodging him ahead of well-known tiger tacklers Joseph Clifford of The Marshes, Ansons River (27 adults and 2 juveniles) and Robert Stevenson of Blessington (26 adults).[5] After Ford’s death in September 1899, Stanley storekeeper Collins claimed bounties for 40 adults and 4 juveniles 1900–06, his successful bounty applications neatly dovetailing with those of Ford.[6]

William Bennett Collins (standing at back) and family, courtesy of Judy Hick.

WB Collins’ Stanley store, AV Chester photo, Weekly Courier, 25 February 1905, p.20.

Where did their combined 75 tigers come from? The biggest source of dead thylacines in the far north-west at this time was Woolnorth. Twenty-six adult tigers were taken at Woolnorth in the years 1891–99, and 44 adults in the years 1900–06, making 70 in all. Tables 1 and 2 show rough correlations between Woolnorth killings and government bounty claims made by Ford and Collins. Ford, for example, received 7 payments 1892–93, the same figure for Woolnorth, while in the years 1894–97 his figure was 13 adults and theirs 16. Similarly (see Table 2), Collins claimed 16 adult and 4 juvenile bounties in 1900, a year in which 22 adult tigers were killed at Woolnorth; while in 1901 the comparative figures were 17 and 9. (Some of the data for Woolnorth is skewed by being recorded only in annual statements, which makes it look as though most tigers were killed in December. This was not the case: the December figures represent killings over the course of the whole year.) Clearly the Woolnorth tigers did not represent all the bounties claimed by Ford and Collins, but likely these made up the majority of their claims.

Table 1: CT Ford bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1891–99

| CT Ford |

29 – 2 |

Woolnorth |

26 – 0 |

| 31 July 1891 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 21 July 1892 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 9 Jany 1893 |

1 adult |

31 Dec 1892 |

2 adults |

| 27 April 1893 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 5 May 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 19 June 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 24 July 1893 |

1 adult |

18 Dec 1893 |

5 adults |

| 23 Jany 1894 |

2 adults |

20 Dec 1894 |

3 adults |

| 24 Feby 1896 |

5 adults |

30 Dec 1895 |

4 adults |

| 5 March 1897 |

1 adult |

7 Jany 1896 |

2 adults |

| 22 Sept 1897 |

3 adults |

19 Dec 1896 |

3 adults |

| 4 Nov 1897 |

2 adults |

Dec 1897 |

4 adults |

| 1 Feby 1898 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 2 August 1898 |

2 adults |

Dec 1898 |

3 adults |

| 30 May 1899 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

2 young |

|

|

Table 2: WB Collins bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1900–12

| WB Collins |

40 – 4 |

Woolnorth |

44 |

| 27 Feby 1900 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 16 Aug 1900 |

5 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1900 |

4 adults |

|

|

| 15 Nov 1900 |

4 adults, 4 young |

Dec 1900 |

22 adults |

| 13 Mar 1901 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 31 July 1901 |

7 adults |

|

|

| 28 Aug 1901 |

6 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1901 |

9 adults |

| 5 Nov 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1902 |

3 adults |

| 7 May 1903 |

2 adults |

Nov 1903 |

8 adults |

| 17 Nov 1903 |

4 adults |

1904 |

1 adult, 1 young (Warde) |

| 21 June 1906 |

1 adult |

1906 |

1 adult |

It would not have been difficult for Ford to act as a go-between for Woolnorth workers.[7] He had grazing land at Montagu and Marrawah/South Downs, east and south of Woolnorth respectively, and would have travelled via Woolnorth to reach the latter. He was also a supplier of cattle and other produce to Zeehan, a wheeler and dealer who bought up Circular Head produce to add to his consignments of livestock to the West Coast.[8] It would have been a simple thing for him on his way home from a Zeehan cattle drive to collect native animal skins and tiger skins/heads from the homestead at Woolnorth, presumably taking a commission for himself in his role as intermediary.

Of course that is not the only possible explanation for Ford’s bounty payments. His brothers Henry Flinders (Harry) Ford (three adults) and William Wilbraham Ford (6 adults) both claimed thylacine bounties. They had a cattle run at Sandy Cape, while William had another station at Whales Head (Temma) on the West Coast stock route.[9] It is possible that all the Ford government thylacine bounty payments represented tigers killed on their own grazing runs and/or in the course of West Coast cattle drives. CT Ford did, after all, take up land at Green Point, the place where the VDL Co killed most of its tigers in the nineteenth century. However, if the Fords killed a lot of tigers on their own properties or during cattle drives you would expect to see some evidence for it, such as in newspaper reports or letters. The Fords were, after all, not only VDL Co manager James Norton Smith’s in-laws, but variously his tenants, neighbours and fellow cattlemen. No evidence has been found in VDL Co correspondence. Oddly, when CT Ford shot himself at home in 1899, it was reported to police by his supposed employee George Wainwright—the same name as the Woolnorth tigerman of that time.[10] Perhaps this was the tigerman’s son George Wainwright junior, who would then have been about sixteen years old, and if so it shows that tigerman and presumed proxy bounty collector knew each other.

For all his 44 bounty claims, storekeeper WB Collins possibly never saw a living thylacine, let alone killed one. After Ford’s death, Collins appears to have established an on-going relationship with Woolnorth, being paid for three bounties in February 1900 before his store even opened for business. The VDL Co correspondence contains plenty of evidence that Collins dealt regularly with Woolnorth as a supplier and skins dealer.

The puzzle of Spurling’s sack of tiger heads

The only problem is Spurling. His claim about the 20 tiger heads being presented to the Stanley Police as a bounty claim doesn’t make a lot of sense. There is no record of such an event in the Stanley Police Station books, although, admittedly, tiger bounty payments rarely turn up in police station duty books or daily records of crime occurrences.[11] Still, 20 bounty claims presented at once would constitute a noteworthy event. The ‘almost W coast’ cattle station to which Spurling referred can only have been Woolnorth or a farm south of there, but his recollection seems wildly inaccurate..

If we assume Spurling got the year right, 1902, we can try to fix on an approximate date for his sack of tiger heads. Spurling photos of Stanley appeared in the Weekly Courier newspaper on 26 April 1902. If we assume that taking these photos provided the occasion for the photographer to meet the tiger heads, we are confined to government bounty payments for the first four months of that year. Less than 20 bounties were paid across Tasmania during that time, and there were no bulk payments of the kind described by Spurling—nor did any bulk payments occur at any time during the year 1902.

Did Spurling get the year wrong? If the 20 heads came from Woolnorth and were supplied in bulk, the time was probably late 1900, the first year in decades in which more than 20 tigers were taken there. Did Spurling see someone from Collins’ store bring in heads from Woolnorth? Not even that seems likely. In February 1900 Collins collected bounties for three adult thylacines; another 5 adults followed in July; in September he collected on another 4; and in October he presented 4 adults and 4 cubs: 20 animals in all, spread over a period of eight months, not in one hit.[12] Saving those 20 heads secured over a period of months for presentation in one hit would be a—frankly—disgusting task given their inevitable state of putrefaction. Spurling’s sack of heads didn’t represent Collins or Woolnorth. No one—no bounty applicant from any part of Tasmania, let alone a group of Woolnorth employees—was ever paid 20 bounties in one hit. The basis of his claim remains a mystery.

[1] See Nic Haygarth, Wonderstruck: treasuring Tasmania’s caves and karst, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.63–69.

[2] Stephen Spurling III, ‘The Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus’, Journal of the Bengal Natural History Society, vol.XVIII, no,2, October 1943, p.56.

[3] Nicholls: bounties no.289, 14 January 1889, p.127 (4 adults); and no.126, 29 April 1889, p.133 (2 adults), LSD247/1/1. Warde: bounty no.190, 20 October 1904 (1 adult and 1 juvenile), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[4] Bounties no.365, 31 July 1891 (2 adults); no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.402, 9 January 1893; no.71, 27 April 1893 (2 adults); no.91, 5 May 1893; no.125, 19 June 1893; no.183, 24 July 1893, no.4, 23 January 1894 (2 adults); no.239, 22 September 1897 (3 adults, ‘August 2’); no.276, 4 November 1897 (2 adults, ’27 October’); no.379, 1 February 1898 (‘4 December’); no.191, 2 August 1898 (2 adults, ‘7 July’); no.158, 30 May 1899 (’26 May’); no.253, 30 August 1899 (3 adults, ’24 August’); no.254, 30 August 1899 (2 juveniles, ‘24 August’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[5] Bounties no.304, 24 February 1896 (5 adults); and no.37, 5 March 1897, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[6] Bounties no.43, 27 February 1900 (3 adults, ’22 February’); no.250, 16 August 1900 (5 adults, ’26 July’); no.316, 3 October 1900 (4 adults, ’27 September’); no.398, 15 November 1900 (4 adults and 4 juveniles, ’28 October’); no.79, 13 March 1901 (2 adults, ’28 February’); no.340, 31 July 1901 (7 adults, ’25 July’); no.393, 28 August 1901 (6 adults, ‘2/3 August’); no.448, 3 October 1901 (’26 September’); no.509, 5 November 1901 (’24 October 1901’); no.218, 7 May 1903 (2 adults, ’24 April’); no.724, 17 November 1903 (4 adults); no.581, 21 June 1906, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[7] Woolnorth farm journals, VDL277/1/1–33 (TAHO). The Woolnorth figure for 1900–06 excludes one adult and one juvenile killed by Ernest Warde and for which he claimed the government bounty payment himself (bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, LSD247/1/2 [TAHO]).

[8] ‘Circular Head harvest prospects’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 19 January 1895, p.2.

[9] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1898, p.184; 1899, p.305.

[10] 10 September 1899, Daily record of crime occurrences, Stanley Police Station, POL93/1/1 (TAHO).

[11] Stanley Police Station duty book, POL92/1/1; Daily record of crime occurrences, POL93/1/1 (TAHO). Daily records of crime occurrences often include information not of a criminal nature.

[12] Bounties no.43, 22 February 1900 (three adults); no.250, 16 August 1900 (five adults); no.316, 27 September 1900 (four adults); and no.398, 28 October 1900 (four adults and four juveniles), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 28/08/21 | Story of the thylacine

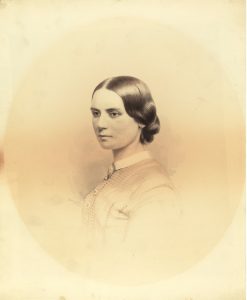

One of north-eastern Tasmania’s greatest hunters was Joseph Clifford (1856–1932), a bush farmer at The Marshes, on Ansons River.[1] Clifford was an incidental snarer of tigers who cottoned onto the live tiger trade as they grew scarcer and more valuable. He was born to ex-convict farmer John Clifford (c1822–1919) and bounty immigrant Mary Ann Lock (aka Anne Viney, c1828–94) at Georges Bay (St Helens).[2] In 1879, as an illiterate 23-year-old farmer, Joseph married 20-year-old farmer’s daughter Emma Summers (c1859–1937).[3] Their four sons and two daughters grew up at The Marshes, where the marshland stretched along both sides of the Anson River and the herbage was plentiful for the stock.[4]

A young Joseph Clifford, courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

Emma and Joseph Clifford at The Marshes, courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

Tigers were also relatively plentiful. In August 1889 a ‘case of native tigers’ was shipped out of Boobyalla to Launceston on the coastal trader Dorset.[5] It was a mother and three cubs destined for William McGowan, manager of the zoo in Launceston’s City Park, who received 21 live thylacines, mostly from the north-east, between June 1885 and July 1893.[6] Perhaps some of them came from Grodens Marsh, across the river from the house at The Marshes. Here Joseph Clifford claimed to have seen a tiger sneak amongst the sheep in order to kill a lamb. He believed that tigers struck the sheep at dusk or dawn, particularly in foggy conditions, taking motherless lambs and any weak ewes. He claimed to have seen as many as nine tigers at one time and developed the belief that they hunted in packs. When the working dogs dragged their chains into their kennels with fear, Joseph released the so-called staghounds, hunting dogs, to tackle the interlopers.[7] These dogs were a mix of great Dane and greyhound, and while used chiefly in possuming they had no fear of tigers.[8]

The Marshes, Ansons River, as it looked from the air in 1969, when the old home and barn still stood. At centre left, across the river from the house, is Grodens Marsh. From aerial photo 528_161, courtesy of DPIPWE.

On one occasion, at a place called the Thomas, Joseph came across five tigers chasing a bandicoot. Most of his staghounds pursued the group, but one dog went after a tiger that broke away on its own. His third son Harry Clifford (c1891–1974) recalled that:

‘When he [Joseph] got down to where the other two [the lone dog and the lone tiger] was they was [sic] both standing up on their hind legs like two dogs fighting’.[9]

The old house at The Marshes, courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

Harry and Emma, his mother, were both scared of tigers. Harry recalled his mother telling him that she saw tigers killing their sheep. One time as Joseph arrived home from a hunting trip, Emma said, ‘Oh the tigers have been here again after the sheep.’ ‘Why didn’t you let the dogs loose?’, Joseph replied. ‘Of course’, said Harry, looking back, ‘she was too scared to go out’. On another occasion when the dogs were let loose they ran down a tiger at Dead Horse Creek, east of the homestead. Harry recalled that ‘the next day the others [other tigers] set up in the little paddock down there howling like dogs’, as if lamenting a missing family member.[10]

Joseph claimed government bounties for perhaps 27 adult and 2 juvenile thylacines (worth £28) in the period 1892–1903, including at least 5 adults in 1897.[11] These would have been incidental killings in the course of landing thousands of kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons and brush and ringtail possums. Snaring was essential to the survival of many poor bush families, and the temptation to snare illegally out of season, tanning skins to sell locally, was strong. In 1905 Joseph suffered a serious setback when a zealous constable found a stash of 337 possum skins and some kangaroo skins concealed under a hay stack at The Marshes out of season, for which he was fined a very hefty £59 17 shillings.[12] He would have needed a very good legal hunting season to make up for it.

The switch to the live tiger trade

While the demand for live tigers was low, there was insufficient inducement for some hunters to undertake the considerable trouble involved in keeping them alive and getting them to market. Sarah Mitchell of Lisdillon near Swansea, for example, was offered £6 for a live tiger by the Sydney Zoological Society in 1890 but ended up £5 out of pocket when it died in transit.[13]

The price of a live tiger had probably increased by 1901, when Joseph Clifford brought a thylacine threesome home on the back of a horse, apparently having snared the mother without killing her.[14] He kept the mother and two pups in a barn at The Marshes, with the idea of selling them, but he couldn’t get them to eat. He caught live native hens and wallabies to feed them but the captives took no interest. Finally the thylacine family starved to death, leaving Joseph to claim £2 for presentation of their carcasses under the government bounty scheme and whatever additional money he could get for the skins themselves.[15]

The barn at The Marshes in which Joseph Clifford kept the live tigers. Harry Clifford is the man in the hat. Photo courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

This incident brought about a change in thinking. Joseph originally used necker snares, with the intention of killing his prey, but now he switched over to footer or treadle snares in order to spare tiger lives and collect a bigger prize.[16] Reasoning that thylacines might survive longer in something resembling their natural habitat, he built an enclosure for them on a marsh at nearby Wurrawa. It was a chicken-wire pen about six metres long by two wide, with tall timber posts.[17] It was here that Harry Clifford remembered his father teaching him, as a teenager, to immobilise a tiger by grabbing its tail from behind and lifting its hind quarters off the ground.[18] How many live tigers the Cliffords caught in the early 1900s and who they sold them to is unknown. The most likely recipient is William McGowan of Launceston’s City Park Zoo, who received six tigers June 1898–June 1901 (three of those are known to have come from the Great Western Tiers), and another 24 June 1901–February 1906.[19] Mary Grant Roberts of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point in Hobart also started buying tigers in 1909, followed by James Harrison of Wynyard in 1910, but as mentioned previously there were also mainland buyers.

Harry Clifford’s tiger experiences

Harry Clifford saw at least fifteen tigers during the first half of his life, without even going out of his way.[20] ‘We didn’t go shooting tigers’, he asserted. ‘They came to us’, that is, they entered the Clifford property and ended up in Clifford snares mostly set for other animals. However, Harry did set two tiger traps at The Marshes, both like heavy duty rabbit traps. He placed one on a crossing log on the Anson River, a typical setting for a snarer, but it seems he never landed his intended prey.

Harry Clifford, photo courtesy of Andrea Richards and Deb Groves.

On one occasion while snaring Harry Clifford met a female tiger on a track. He had just slung a wallaby over his shoulder which he had taken out of a snare. As he advanced towards the next snare his dogs grew excited and began to retreat behind him, betraying what lay ahead. Harry was not the first person to assert that a tiger on a track would not move out of the way of a human.[21] The female sat steadfastly on the track ahead of him. Guessing that the object of her interest was the large slab of fresh meat on his shoulder, he slowly lowered it to the ground in front of him and backed off. As the tiger grabbed the wallaby, three pups emerged from the scrub to feed. Next day when Harry returned only the skeleton of the wallaby remained.

Harry believed that a thylacine would rip a hole in a sheep under the front leg where there was no wool and bore a hole into the rib cage in order to eat the internal organs. It would eat the kidneys, heart and lungs, and also take the meat off the back legs. A tiger, he said, could eat bandicoots and rabbits whole. It would catch bandicoots in tussocks, pouncing like a cat nose first, holding the tussock with its front paws as it pulled the prey out with its teeth.[22]

[1] ‘Priory: late Mr Joseph Clifford’, Examiner, 16 November 1932, p.5.

[2] Born 2 January 1856, birth record no.276/1856, registered at Fingal, RGD33/1/34 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=joseph&qu=clifford#, accessed 22 April 2019. For John Clifford as a convict, see marriage permission 31 March 1848, CON52/1/2, p.307 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=clifford&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriage+Permissions%09Marriage+Permissions, accessed 22 April 2019.

[3] Married 15 December 1879, marriage record no.656/1879, married at Georges Bay, registered at Portland, RGD37/1/38 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=joseph&qu=clifford, accessed 22 April 2019. Emma Clifford died 17 November 1937, aged 78, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery. The four sons were Joseph (born 1880), John (‘Ginger Jack’, born 1889), Henry (Harry, c1891–1974), James (1893–1920). The two daughters were Emma Ann Jane (born 1896) and Amy Florence (‘Florrie’) (1899–1923).

[4] ‘Priory: late Mr Joseph Clifford’, Examiner, 16 November 1932, p.5. Henry (Harry) Clifford died 19 November 1974, aged 83, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery. See will no.60025, AD960/1/151 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=henry&qu=clifford&isd=true, accessed 10 June 2020. James Clifford died 25 June 1920, aged 26, buried at the St Helens General Cemetery.

[5] ‘Shipping intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 19 August 1889, p.2.

[6] ‘Local and general’, Tasmanian, 24 August 1889, p.23; Robert Paddle, ‘The thylacine’s last straw: epidemic disease in a recent mammalian extinction’, Australian Zoologist, vol. 36, no.1, 2012, p.76.

[7] ‘Anson Marshes’, Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1922, p.6; Clifford family information from Deb Groves, 16 November 2019.

[8] John Morling, St Helens, interviewed by Deb Groves, 2019.

[9] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[10] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970.

[11] That is, 15 adults and 2 juveniles in the name of Josh Clifford, and 12 adults in the name of J Clifford. Josh Clifford: bounties no.283, 21 September 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.30, 6 March 1893; no.251, 16 October 1893 (2 adults); no.177, 10 July 1897 (5 adults); no.336, 23 November 1898 (‘5 November’); no.375, 12 January 1899 (‘5 December’); no.88, 27 April 1899 (’15 April’); no.375, 5 December 1899 (’13 November’); no.436, 27 September 1901 (1 adult and 2 juveniles, ’26 August’); no.354, 23 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO). J Clifford: bounties no.734, 11 January 1892; no.118, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.160, 5 July 1893 (2 adults); no.185, 10 October 1895 (2 adults); no.338, 31 July 1901 (5 adults, ’10 July’); no.984, 25 July 1902 (‘9 June’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO). For Joseph Clifford’s 1897 tiger killings see ‘The country’, Daily Telegraph, 22 April 1897, p.4; ‘St Helens’, Daily Telegraph, 23 August 1897, p.3; ‘St Helens’, Mercury, 27 August 1897, p.3.

[12] ‘Gladstone’, Examiner, 7 March 1905, p.6; ‘A heavy fine’, Examiner, 27 March 1905, p.5.

[13] Sarah Mitchell diary, 17 and 19 May, 9 and 26 June 1890 (University of Tasmania Special Collections).

[14] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[15] Jeff Richards, nephew of Harry Clifford; interviewed by Deb Groves. Jeff remembered Harry specifying that there were four or five young with the mother.

[16] John Morling, St Helens, interviewed by Deb Groves, 2019.

[17] Clifford family information from Deb Groves, 16 November 2019.

[18] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[19] Robert Paddle, ‘The thylacine’s last straw …’, pp.76 and 81.

[20] Harry Clifford, interviewed for Radio 7SD, Scottsdale, c1970 (audio held by Deb Groves, Gladstone).

[21] See Robert Stevenson to David Cunningham, 13 November 1941, QVM1/59, part 4, Inward correspondence 1941 (QVMAG). The same incident was reported in ‘Adventure with a native tiger’, Launceston Examiner, 22 March 1899, p.5.

[22] Harry Clifford, interviewed by Deb Groves, c1970.

by Nic Haygarth | 22/10/20 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

By the 1890s farmers like Joseph Clifford and Robert Stevenson were effectively adding Tasmanian tiger farming to their portfolios of raising stock, growing crops and hunting. Since thylacines appeared on their property, they made a conscious effort to catch them alive in a footer snare or pit rather than dead in a necker snare. A tiger grew no valuable wool, but in 1890 a live wether might fetch 13 shillings, compared to £6 for an adult thylacine delivered to Sydney.[1] A dead adult thylacine, on the other hand, was worth only £1 under the government bounty scheme.

The problem with these special efforts to catch tigers alive was that hunters only had a certain amount of control over what animals ended up in their snares or pits. Twentieth-century hunters often complained about city regulators who thought it feasible to close the season on brush possum but open it for wallabies and pademelons. Inevitably, hunters caught some brush possum in their wallaby and pademelon snares during the course of the season, which could land them a hefty fine in court unless they destroyed the precious but unlawful skins.[2] John Pearce junior in the upper Derwent district claimed that he and his brothers caught seventeen tigers in ‘special neck snares’ set alongside their kangaroo snares.[3] How did the tigers recognise the ‘special neck snares’ provided for their specific use? All you could do was vary the height of the necker snare to catch the desired animal’s head as it walked. Too bad if something else stuck its head in the noose. Wombats, for example, were a hazard. Gustav Weindorfer of Cradle Valley set snares at the right height to catch Bennett’s wallabies by the neck, but also caught wombats in them.[4] Wombats were good for ‘badger’ stew and for hearth mats but the skins had no value. Robert Stevenson of Aplico, Blessington, caught wombats alive in his tiger pits—which they then set about destroying by burrowing their way out.[5]

George Wainwright senior, Matilda Wainwright and children at Mount Cameron West (Preminghana) c1900. Courtesy of Kath Medwin.

These problems aside, it seems odd that the pragmatic Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co), which later added fur hunting to its income stream, didn’t cotton on to the live tiger trade. They could have followed the example of George Wainwright senior, who sold a Woolnorth tiger to Fitzgerald’s Circus in 1896.[6] In 1900, for example, 22 thylacines were killed on Woolnorth, a potential income of more than £100 had the animals been taken alive. Even when, later, four living Woolnorth tigers were sold, the money stayed with the employees, with the VDL Co not even taking a commission. (It should be noted that four young tigers caught by Walter Pinkard on Woolnorth in 1901 were not accounted for in bounty payments.[7] It is possible that they were sold alive—but there are no records of a sale or even correspondence about the animals. Their fate is unknown.)

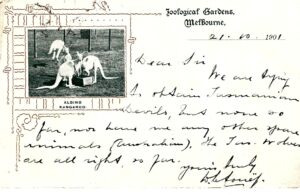

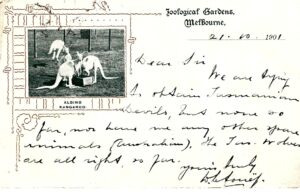

William Le Souef to Kruger, 22 October 1901: ‘The Tasmanian Wolves are all

right, so far’. Did he get them from Woolnorth? Postcard courtesy of Mike Simco.

The VDL Co’s failure to exploit the live trade for its perceived arch enemy can possibly be explained by the tunnel vision of its directors and departing Tasmanian agent and the inexperience of his successor. James Norton Smith resigned as local manager in 1902. His replacement, Scotsman Andrew Kidd (AK) McGaw, harnessed Norton Smith’s 33-year corporate knowledge by re-engaging him as farm manager. It would not have been easy for McGaw to learn the ropes in a new country, among business associates cultivated by his predecessor, and the re-engagement of Norton Smith as his second allowed him to transition into the manager position. As would be expected, McGaw stamped his authority on the agency by criticising some of Norton Smith’s policies and distancing himself from them.[8] Ahead of Ernest Warde’s engagement as ‘tigerman’, the VDL Co’s shepherd at Mount Cameron West, he scrapped Norton Smith’s recent bounty incentive scheme of £2 for a tiger killed by a man out hunting with dogs.

Woolnorth, showing main property features and the original boundary. Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

After Warde’s departure in 1905, the tiger snares at Mount Cameron and Studland Bay were checked intermittently. Woolnorth overseer Thomas Lovell killed a tiger at Studland Bay in 1906, but the number of tigers and dogs reported on the property was now negligible.[9] This reflected the statewide situation, with only eighteen government thylacine bounties being paid in 1907, and only thirteen in 1908.[10]

However, the value of live tigers continued to climb as they became rarer. The first documented approach to the VDL Co for live tigers came in July 1902 from AS Le Souef of the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne, who offered £8 for a pair of adults and £5 for a pair of juveniles. He also wanted devils and tiger cats, in response to which George Wainwright junior supplied two tiger cats (spotted quolls, Dasyurus maculatus).[11] Given the tiger’s reputation as a sheep killer, native animal farming might have been a hard sell to the directors, and the company continued to use necker snares which were generally fatal to thylacines. What price would it take to change that behaviour? In July 1908 McGaw read a newspaper advertisement:

‘WANTED—Five Tasmanian tigers, handsome price for good specimens. Apply Beaumaris, Hobart.’[12]

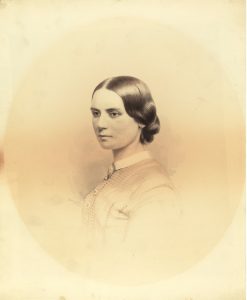

He discovered that the proprietor of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point, Mary Grant Roberts, wanted a pair of living tigers immediately to freight to the London Zoo.[13] The Orient steamer Ortona was departing for London at the end of the month. She offered McGaw £10 for a living, uninjured pair of adults. Roberts hoped to secure the tiger caught recently by George Tripp at Watery Plains, but felt that she was competing for live captures with William McGowan of the City Park Zoo, Launceston, who advertised in the same month.[14] Eroni Brothers Circus was also in the market for living tigers.[15]

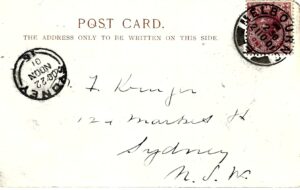

A young Mary Grant Roberts, from NS823/1/69 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

Almost as Roberts made her offer, George Wainwright junior tracked a tiger at Mount Cameron West, but it evaded capture.[16] In the meantime Roberts was able to secure her first thylacine from the Dee River.[17]

Almost a year passed before the chance arose for the VDL Co do business, when in May 1909 Wainwright retrieved a three-quarters-grown male tiger uninjured from a necker snare.[18] Perhaps not appreciating the tiger’s youth, Roberts offered £5 plus the rail freight from either Burnie or Launceston. She wanted the animal delivered to her in Hobart within ten days in order to ship it to the London Zoo on the Persic. It would thereby replace one which had died of heat exhaustion in transit to the same destination a few months earlier.[19]

However, the overseer of a remote stock station could not meet that deadline. The delay came with a bonus—the capture of three more members of the first tiger’s family, his sisters and mother.[20] Bob Wainwright recalled his stepfather Thomas Lovell and brother George placing the animals in a cage. There was also a familiar story of tigers refusing to eat dead game: ‘They had to catch a live wallaby and throw it in, alive, and then they [the thylacines] killed it’.[21] With McGaw continuing to act as intermediary between buyer and supplier, a price of £15 was settled on for the family of four.[22]

Roberts and McGaw communicated as social equals, but their social inferiors—hunters, stockmen and an overseer—were not named in their correspondence. This made for frustrating reading when Roberts discussed hunters (‘the man’) with whom she was dealing over live tigers. She had been expecting to receive two young tigers from a Hamilton hunter for her own zoo, but these had now died, causing her to reconsider her plans for the Woolnorth family.[23]

The mother thylacine (centre) and her three young captured at Woolnorth in 1909. W Williamson photo from the Tasmanian Mail, 25 May 1916, p.18.

It wasn’t until the first week in July 1909 that the auxiliary ketch Gladys bore the crate of thylacines to Burnie, where they began the train journey to Hobart.[24] A week later they were said to be thriving in captivity.[25] Roberts was so pleased with the animals’ progress that after eight months she sent a postal order to Lovell and Wainwright as a mark of appreciation. She was impressed with the mother’s devotion to her young, believing that the death of the two Hamilton cubs was attributable to their mother’s absence.[26] However, money was becoming a concern. Buying all the tigers’ feed from a butcher was expensive, and when she received a potentially lucrative order for a tiger from a New York Zoo, she found the cost of insuring the animal over such a long journey prohibitive. On 1 March 1910 she ‘very reluctantly’ broke up the family group by dispatching the young male to the London Zoo. ‘I am keeping on the two [other juveniles]’, she wrote, ‘in the hope that they may breed, and the mother all along has been very happy with the three young ones’.[27]

Roberts was now offering £10 per adult thylacine—but there was none to sell at Woolnorth. Seventeen months later she paid Power £12 10s for his large tiger from Tyenna, and scored £30 shipping to London the last of the three young from the 1909 family group.[28] Her tiger breeding program was over, probably defeated by economics—but what might have been the rewards for perseverance? Perhaps she would have been the greatest tiger farmer of all.

[1] See, for example, ‘Commercial’, Mercury, 5 August 1890, p.2; Sarah Mitchell diary, 9 June 1890, RS32/20, Royal Society Collection (University of Tasmania Archives).

[2] See, for example, ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[3] ‘Direct communication with the west coast initiated’, Mercury, 1 September 1932, p.12.

[4] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Journal of the Victorian Naturalists Society, vol.36, March 1920, p.159.

[5] Lewis Stevenson, interviewed by Bob Brown, 1 December 1972 (QVMAG).

[6] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[7] Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 19 July 1901, VDL22/1/27 (TAHO).

[8] In Outward Despatch no.46, 4 January 1904, p.366, McGaw criticised Norton Smith for not doing more to arrest the encroachment of sand at Studland Bay and Mount Cameron (VDL7/1/13).

[9] Woolnorth farm diary, 30 September 1906 (VDL277/1/34). This VDL Co bounty was not paid until the following year (December 1907, p.95, VDL129/1/4). C Wilson was paid for killing two dogs found worrying sheep in 1906 (December 1906, p.58, VDL129/1/4 (TAHO).

[10] See thylacine bounty payment records in LSD247/1/3 (TAHO).

[11] AS Le Souef to James Norton Smith, 11 July 1902; Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 4 August 1902, VDL22/1/28 (TAHO).

[12] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 July 1908, p.3.

[13] For Roberts, see Robert Paddle, ‘The most photographed of thylacines: Mary Roberts’ Tyenna male—including a response to Freeman (2005) and a farewell to Laird (1968)’, Australian Zoologist, vol.34, no.4, January 2008, pp.459–70.

[14] In ‘Wanted to buy’, Mercury, 18 July 1908, p.2, McGowan asked for tigers ‘dead or alive’. He had also advertised for ‘tigers … good, sound specimens, high price; also 2 or 3 dead or damaged specimens’ in the previous year (‘Wanted’, Mercury, 21 June 1907, p.2). George Tripp’s tiger must have died before it could be sold alive, since he claimed a government bounty for it (no.35, 25 July 1908, LSD247/1/3 [TAHO]).

[15] See, for example, ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 March 1908, p.6.

[16] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 17 July 1908, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[17] ‘The Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 7 October 1908, p.4.

[18] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 24 May 1909, VDL22/135 (TAHO). This thylacine was originally thought to be a young female, but McGaw later stated that it was a young male.

[19] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 31 May 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[20] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 1 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[21] Bob Wainwright, 86 years old, interviewed in Launceston, 27 October 1980.

[22] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 9 June 1909, VDL52/1/29; Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 10 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[23] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 21 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[24] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 7 July 1909, VDL52/1/29 (TAHO); ‘Stanley’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 July 1909, p.2.

[25] W Roberts to AK McGaw, 15 July 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[26] In May 1912 she received two young tigers from buyer EJ Sidebottom in Launceston, paying him £20 in the belief that they were adults. They died three days later (Mary Grant Roberts diary, 6, 7 and 10 May 1912, NS823/1/8 [TAHO]).

[27] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 14 March 1910, VDL22/1/36 (TAHO).

[28] Mary Grant Roberts diary, 12 August, 26 September and 24 December 1911, NS823/1/8 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 03/04/20 | Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

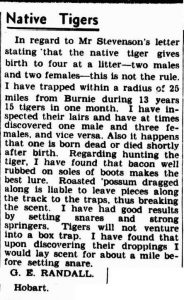

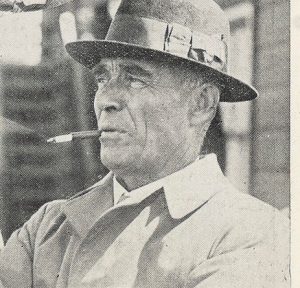

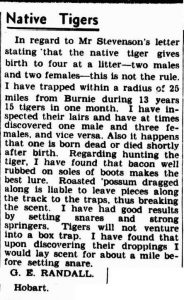

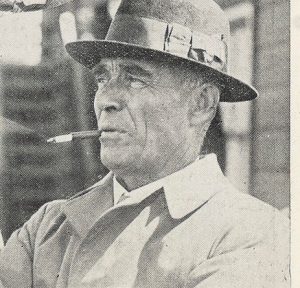

In 1945 one-time wrestler George Randall (1884–1963) recalled catching fifteen thylacines in the space of a month within 25 miles (40 km) of Burnie. He didn’t smother them in a bear hug. Randall reminisced that, upon finding tiger scats, he would lay a scent for half a mile from that point to his snares. The cologne no tiger could resist was actually the smell of bacon rubbed onto the soles of his boots.[1]

Champion wrestler George Randall, from the Weekly Courier, 18 February 1909, p.18.

George Randall in the Mercury, 12 December 1945, p.3.

Fifteen tigers—a big boast indeed. I was suspicious of those numbers. Who was Randall, and if he was such an ace tiger killer why had he never claimed a government thylacine bounty? Government bounties of £1 for an adult tiger and 10 shillings for a juvenile were paid in the years 1888 to 1909, after all, plenty of time in which he could leave his mark. The production of a carcass at a police station was the basis for a bounty application.

Randall was born at Burnie to George Ely Randall (1857–1907) and Emily Randall, née Charles (1871–1938).[2] By 1891 his father George Randall senior was a ganger maintaining the Emu Bay Railway (EBR) at Ridgley, south of Burnie. There were some tigers about, and it didn’t take much effort to find some Randalls killing one. In May 1892 Tom Whitton, who was aware of tigers coming about the gangers’ camp at night, set some snares and caught a large male. Two Randalls, George senior and his brother Charles, plus a fettler named Ted Powell, were at hand to help throttle the beast.

Wellington Times editor Harris added: ‘The tiger’s head was inspected by a large number of persons up to yesterday, many of whom remarked that they had never seen larger from a native animal; but yesterday the head had to be thrown away as it was manifesting signs of decay.’[3]

Thrown away?! So much for the £1 bounty. Perhaps the killers were too bloated on public admission fees to care about the bounty payment.

Another Randall killing came only two months later, when Powell and Charles Randall’s dogs flushed a tiger out of the bush at the 23-Mile on the EBR. Again the body was hauled into Burnie as a trophy.[4] Was a £1 government reward paid?

The government bounty records for the period May–July 1892 show the difficulty of reconciling newspaper reports with official records. There is no evidence of a bounty application having been made for the tiger killed on the EBR on 13 May 1892, but the one destroyed there in the week preceding 12 July 1892 is problematical. Was James Powell, who submitted a bounty application on 8 July, a relation of Ted Powell, the fettler involved in the two killings on the EBR? I could find no record of a James Powell working or residing in the Burnie area at that time, whereas two James Powells in pretty likely tiger-killing professions—manager of a highland grazing run, and bush farmer under the Great Western Tiers—were easily identified through digitised newspaper and genealogical records (see Table 1):

Table 1: Government thylacine bounty payments, May–July 1892, from Register of general accounts passed to the Treasury for payment, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

| Name |

Identification |

Application date |

Number |

| G Atkinson |

Probably farmer George Elisha Atkinson of Rosevears, West Tamar |

13 June 1892 |

2 adults[5] |

| A Berry |

Probably shepherd Alfred James Berry, Great Lake, Central Plateau |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[6] |

| John Cahill |

Farmer/prospector, Stonehurst, Buckland, east coast |

8 July 1892 |

1 adult[7] |

| WF Calvert |

Wool-grower/orchardist William Frederick Crace Calvert, Gala, Cranbrook, east coast |

21 July 1892 |

4 adults[8] |

| J Clifford |

Probably bush farmer/hunter Joseph Clifford of Ansons Marsh, north-east |

12 May 1892 |

1 adult[9] |

| Harry Davis |

Mine manager, Ben Lomond, eastern interior |

31 May 1892 |

2 adults & 1 juvenile[10] |

| CT Ford |

Mixed farmer Charles Tasman Ford, Stanley, north-west coast |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[11] |

| Thomas Freeman |

Shepherd at Benham, Avoca, northern Midlands |

12 May 1892 |

1 adult[12] |

| E Hawkins |

Shepherd William Edward Hawkins, Cranbrook, east coast |

9 July 1892 |

1 adult[13] |

| E Hawkins |

Shepherd William Edward Hawkins, Cranbrook, east coast |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[14] |

| Thomas Kaye |

Labourer at Deddington, northern Midlands |

31 May 1892 |

1 adult[15] |

| John Marsh |

John Richard James Marsh of Dee Bridge, Derwent Valley |

27 June 1892 |

1 adult & 1 juvenile[16] |

| W Moore junior |

Bush farmer William Moore junior, Sprent, north-western interior |

13 June 1892 |

1 adult[17] |

| E Parker |

Probably grazier Erskine James Rainy Parker of Parknook south of Cressy, northern Midlands |

27 June 1892 |

2 adults[18] |

| James Powell |

Probably manager, Nags Head Estate, Lake Sorell, Central Plateau, or bush farmer, Blackwood Creek, northern Midlands |

8 July 1892 |

1 adult[19] |

| Charles Pyke |

Mail contractor, Spring Vale, Cranbrook, east coast |

27 June 1892 |

1 adult[20] |

| A Stannard |

Probably shepherd Alfred Thomas David Stannard, native of Mint Moor, Dee, Derwent Valley but thought to have been in the northern Midlands at this time |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[21] |

| D Temple |

Shepherd David Temple senior, Rocky Marsh, Ouse, Derwent Valley |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[22] |

| R Thornbury |

Farmer Roger Ernest Thornbury, Bicheno, east coast |

12 May 1892 |

1 adult[23] |

| H Towns |

Farmer Henry Towns, Auburn, near Oatlands, southern Midlands |

20 June 1892 |

1 adult[24] |

The two EBR slayings are not the only known tiger killings missing from the bounty payment record: two young men reportedly snared a live tiger near Waratah at the beginning of May 1892, but the detained animal accidentally hanged itself on its chain in a blacksmith’s shop; while on 22 July 1892 well-known prospector/sometime postman and seaman Axel Tengdahl shot a tiger that broke a springer snare on the Mount Housetop tinfield.[25] (Another July 1892 killing by ‘Bill the Sailor’ Casey at Boomers Bottom, Connorville, Great Western Tiers, was not rewarded until 5 August 1892, a lag of almost a month.[26]) The reasons for the Waratah and Housetop killings going unrewarded are not clear. While Tengdahl was in an inconvenient place to submit a tiger carcass to a police station, he was probably also snaring for cash as well as meat, so would have needed to leave the bush anyway in order to sell his skins to a registered buyer.

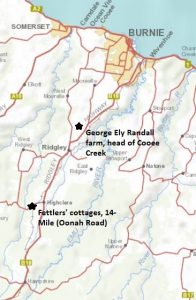

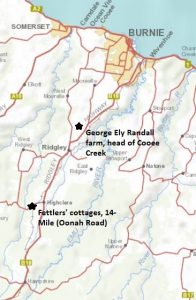

Anyway, back to Randall the tiger tamer. We know that young George Randall junior, eight years old in 1892, grew up with his elders hunting and chasing tigers. Then he went out on his own. He claimed that he trapped within a 40-km radius of Burnie for thirteen years, and that sometime during that period, in the space of a month, he killed fifteen tigers. It should be easy enough to figure out when this was. The ten-year-old would have been still living along the EBR with his family and presumably at school in 1894 when his mother was judged to be of unsound mind and committed to the New Norfolk Asylum.[27] In the years 1897–1901 (from the age of thirteen to seventeen) he was an apprentice blacksmith while living with his father at the 14-Mile (Oonah).[28] [29] He was still in the Burnie area in 1902 when he was cutting wood for James Smillie and driving a float for JW Smithies, but in 1903, as a nineteen-year-old, he was an insolvent fettler at Rouses Camp near Waratah.[30]

Emu Bay Railway south of Burnie, showing sites that George Randall may have hunted from. Base map courtesy of DPIPWE/

By 1907 Randall was a married man working at Dundas.[31] He did not return to the Burnie region after that, doing the rounds of Tasmania’s mining fields and rural districts for two decades with intermissions at Devonport, Hobart and Hokitika, the little mining port on the west coast of New Zealand’s South Island.[32] At Zeehan he was described as ‘the champion [wrestler] of Tasmania’, and he was noted not as a hunter but as a weightlifter and athlete.[33] More importantly, the blacksmith qualified as an engine driver and a winding engine driver, making him eminently employable in resource industries.[34] Randall finally settled at Hobart in 1929 at the age of 45.[35]

If we consider his Rouses Camp fettling a short aberration, the thirteen-year period in which Randall hunted around Burnie could have been approximately 1894 to 1906, that is, between the ages of ten and 22. The government bounty was available for the whole of this time, so why is there no record of George Randall’s prowess as a tiger tamer?

There are two possibilities. One is that Randall, a born showman, simply lied. The other possibility is that he killed or captured (he doesn’t say which) a lot of tigers but the evidence of same is hard to find.[36] There are few surviving records of the sale of live thylacines to zoos or animal dealers, or of bounty applications made through an intermediary like a hawker or shopkeeper. In some cases suspicion of acting as an intermediary even attaches to farmers—such as Charles Tasman (CT) Ford.

In later life Guildford’s Edward Brown assumed respectability as a breeder of race horses and hotelier. Stephen Spurling III photo from the Weekly Courier, 16 November 1922, p.28.

Randall may have been rewarded for fifteen thylacine carcasses through intermediaries such as shopkeepers, hawkers, skin buyers or some regular traveller to Burnie. Hunter/skin buyers such as Thomas Allen (15 adults and a juvenile, 1899–03)[40] and Edward Brown (7 adults, 1904–05)[41] operated in the Ridgley-Guildford area along the railway line, possibly accounting for some bounty payments for the likes of Randall, ‘Black Harry’ Williams, ‘Five-fingered Tom’ Jeffries and Bill Todd.

However, it does seem extraordinary that fifteen tiger captures or kills within the space of a month escaped public attention. We can assume that Randall never anticipated the scrutiny of his life that digitisation of records now allows us, let alone that someone who read his 1945 letter in the next century would try to dissect his life in order to verify his words. It is likely that Randall guessed that he had hunted in the Burnie region for thirteen years. Perhaps it was ten years, and perhaps his tigers took a lot longer to secure. Perhaps in a trunk in an attic somewhere is a mouldering trophy photo of the wrestler who wrangled tigers—dead or alive.

[1] GE Randall, ‘Native tigers’, Mercury, 12 December 1945, p.3.

[2] Born 1 July 1884, birth record no.1298/1884, registered at Emu Bay; died 14 July 1963, will no.44135, AD960/1/95, p.911 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall#, accessed 28 March 2020.

[3] ‘Capture of a native tiger’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 12 May 1892, p.2.

[4] ‘A big tiger’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 12 July 1892, p.2.

[5] Bounty no.147, 13 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[6] Bounty no.207, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[7] Bounty no.190, 8 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[8] Bounty no.203, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[9] Bounty no.118, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[10] Bounty no.136, 31 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[11] Bounty no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] Bounty no.119, 12 May 1892; LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[13] Bounty no.188, 9 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[14] Bounty no.210, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[15] Bounty no.135, 31 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[16] Bounty no.173, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[17] Bounty no.148, 13 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[18] Bounty no.172, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[19] Bounty no.189, 8 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[20] Bounty no.171, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[21] Bounty no.206, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Bounty no.208, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[23] Bounty no.117, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[24] Bounty no.151, 20 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[25] ‘Waratah notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 10 May 1892, p.3; ‘Housetop notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 28 July 1892, p.2.

[26] ‘Longford notes’, Launceston Examiner, 14 July 1892, p.2; bounty no.236, 5 August 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[27] ‘Burnie: Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 7 February 1894, p.1.

[28] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 July 1901, p.3.

[29] ‘For sale’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 31 January 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Arson: case at Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 20 March 1902, p.3; ‘New insolvent’, Examiner, 29 April 1903, p.4.

[31] He married Ethel May Jones on 22 May 1907 at North Hobart (‘Silver wedding’, Mercury, 23 May 1932, p.1). Dundas: ‘To-night at the Gaiety’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 7 September 1907, p.3.

[32] Zeehan: Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 August 1908, p.2; ‘Macquarie district’, Police Gazette Tasmania, vol.48, no.2595, 16 April 1909, p.81; Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Darwin, Subdivision of Zeehan, 1914, p.2. Devonport: Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Devonport, 1914, p.36. Waratah: ‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 17 October 1918, p.2; Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Darwin, Subdivision of Waratah, 1919, p.14. Hobart: Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Denison, Subdivision of Hobart East, 1922, p.30. Mathinna: ‘Personal’, Daily Telegraph, 30 September 1924, p.5. Cygnet: ‘Shooting at electric lines’, Mercury, 28 June 1926, p.4. Taranna: ‘Centralisation of school teaching’, Mercury, 12 May 1927, p.6. Hokitika: ‘Macquarie district’.

[33] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 August 1908, p.2; ‘Macquarie district’.

[34] Certificate of competency as second class engine drive, 1916, AA80/1/1, p.424, image 63 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall; Certificate of competency as mining engine driver, 1926, LID24/1/4, pp.109 and 109b (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall#, accessed 28 March 2020.

[35] ‘Motor cycle registrations’, Police Gazette Tasmania, vol.68, no.3629, 8 February 1929, p.33.

[36] Randall mentioned using springers, the supple saplings used to ‘spring’ the snare, generally employed in footer snares, which caught the animal by the paw, not being designed to kill it. Many thylacines sent to zoos were captured in footer snares.