The story of Balfour is told by two graves in a highland cemetery in north-western Tasmania. For more than a century, lying side by side, William Murray and Sylvia McArthur have been fixed silently in their interlocking roles in what historian Geoffrey Blainey called the ‘Indian summer’ of Tasmania’s first mining boom. Why did they ever live in this remote place?

They were both casualties of frenzied speculation that Balfour would become a second Mount Lyell copper field. Part one of this story concerns William Wallace Fullarton Murray junior (1861–1912), manager of the Copper Reward (Murrays’ Reward) mine which generated this excitement. He received a fighting pedigree from both parents. William Murray’s paternal grandfather, a captain in the 91st regiment, was reputedly a hero of the Battle of Trafalgar. His father, William Wallace Fullarton Murray senior (1820–94), a Church of England minister, was brought to Tasmania from England to tutor the children of Governor Sir William Dennison, after which he served as chaplain of New Norfolk (St Matthew’s Church) for 39 years. William senior married Augusta Schaw, the sixth daughter of Major Schaw, a police magistrate formerly of the 21st Fusiliers.[1]

Such an impressive lineage demanded a private school education, which young William and his brother Thomas Charles Murray (1862–1938) received, but their upbringing, along with that of their six sisters, was relatively modest.[2] Although Tom was a mad-keen prospector, it was actually their sister Kate who led the Murray brothers to what became known as the Copper Reward mine near Mount Balfour, far from their home town of New Norfolk. Kate married William Wilbraham Ford, a Circular Head farmer, who grub-staked a prospector, Frederick Henry Smith.[3] Smith discovered copper on Tin Creek near Mount Balfour, which had been a sparsely-visited alluvial tin field for two decades. In 1901 Tom Murray helped him peg the discovery and applied for a reward claim under the Mining Act (1900). Tom and William Murray, Fred Smith and William Ford took a quarter share each in the mine, Ford apparently helping to finance and promote its development.[4] The remote claim was not surveyed until 1905, by which time Smith’s whereabouts were unknown. The lease was finally issued in 1907 to Tom Murray and in trust for others interested. Having abandoned their unprofitable gold leases at Woody Hill near Queenstown, the Murray brothers worked their reward claim continuously from February 1907.[5] To relieve financial pressure a fifth share in the mine (rumoured to be Robert Sticht, general manager of the Mount Lyell Company) was introduced.[6]

The Murrays built a farm—now known as Kaywood—with an extensive vegetable garden near the hazardous port of Whales Head (Temma). Six-horse wagons delivered ore from the mine to the brothers’ store shed at Temma, awaiting the fortnightly visits of the auxiliary ketch Gladys which bore it to market. Without even a jetty, loading and offloading at Temma involved a rowboat meeting a dray driven into the water.[7]

By the spring of 1909, investors were agog at the 1100 tons of ore, averaging about 30% copper, which the Murrays had reportedly dispatched. In addition, three or four times as much high grade ore was said to have been ‘at grass’ on the property. In October 1909 a report circulated that the brothers had sold the Copper Reward mine for £50,000 and an interest in a company with a big working capital—a claim the Murrays denied.[8] Meanwhile a township named after nearby Mount Balfour developed.

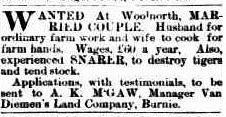

The entire mining field appears to have been invigorated by developments at the Copper Reward. Mount Lyell was stamped all over the speculation boom that followed. The Central Mount Balfour Company, with Mt Lyell Co directors Aloysius Kelly and Herman Schlapp in prominent roles, was floated in Melbourne with £25,000 subscribed capital. The adjoining Balfour Blocks Company had Mount Lyell supremo Bowes Kelly as chairman of directors. Meanwhile, veteran prospector and explorer Thomas Bather (TB) Moore dug away at the Norfolk Ranges at the behest of his boss, Robert Sticht.[9] In May 1910 the first sod was turned on the Stanley to Balfour Railway, a farcical grab at timber and hydro-electric power concessions by the Melbourne promoters of the Mount Balfour Copper Mines NL, now styling themselves the Mount Balfour Mining and Railway Company—mimicking the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company.[10]

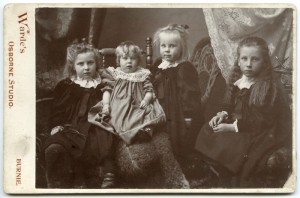

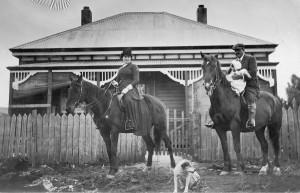

It must have been tempting for the Murray brothers to start living the good life that the speculation promised, and which could easily have landed them in debt. Forty-eight-year-old William took an eighteen-year-old wife, Melbourne-born Hazel, née Myers (1891–1973).[11] Married in Sydney, the couple honeymooned first at Jenolan Caves, then in England while their Balfour home was built.[12] The Circular Head Chronicle noted that the house, with its concrete double chimneys, would provide ‘a magnificent contrast to our present canvas and paling humpies, to say nothing of those described by a recent visitors as being made of opened out sardine tins’.[13] TB Moore referred to the Murrays’ house as ‘the mansion’.[14] It is possible that Hazel Murray wasn’t quite so impressed with it when, in mid-1911, following on from their antipodean jaunt, William brought his young bride, baby and maid to Balfour via stage coach and the new horse-drawn tramway from Temma.[15] How happy the couple seems in the photo, with Hazel astride her horse, and William clutching their first daughter, Jean Wallace Murray.[16] Did Hazel adjust to frontier living, or did she ‘fly’ back to ‘civilisation’?

The fate of the Murray brothers is a staple of Tasmanian mining folklore, even being the subject of a play.[17] William Murray shot himself in his home at Donald Street, Balfour, in November 1912, reputedly as part of an unfulfilled double suicide pact with his brother Tom.[18] William was a quiet and private man: only he would know why he suicided. In her description of William and Hazel Murray’s wedding, the social writer for the Star newspaper referred to the brothers by their second names, Wallace and Charles: perhaps they had new social pretensions in Sydney. Had the Murrays missed their big chance to sell the mine, had dreams of marriage and riches crashed? It has been claimed that they refused an offer of £30,000 for a mine that ultimately proved a failure.[19] However, it had not failed at the time of William Murray’s death, and the copper price was starting to recover from the 1907 crash. It was sadly appropriate that William’s death was overshadowed by the tragedy of the North Mount Lyell fire, which killed 42 miners.[20]

William Murray bequeathed Hazel his life insurance policy to the value of £250—providing death by suicide was covered. She would not have been able to claim on an accident policy to the same value. She also received half the value of his mining interests, the other half being divided between his brother Tom Murray and others.[21] Perhaps debts absorbed all this and more. In 1913, 22-year-old mother-of-two Hazel was operating a boarding house at Battery Point, Hobart, but later she appears to have returned to her family.[22] Little is known about her life in Sydney. Her second daughter, Mary Fullarton Murray, married in 1937, but the other, Jean, had an unhappy love affair, suing her lover for £1000 in 1942 for breach of marriage contract.[23]

Tom Murray reputedly suffered a mental breakdown after his brother’s suicide, although he was apparently fit enough to walk from Hobart to Balfour to tend William’s grave.[24] Certainly he seems to have led a listless life, returning to Balfour in 1916 and 1920, then selling up his farm at Forest in 1924 with the intention of leaving the state.[25] Tom hunted osmiridium at Adamsfield two years later.[26] Described as having ‘no occupation’ and being ‘late of Roger River’, he died intestate at Latrobe in 1938, aged 75.[27] The Copper Reward mine remains untested at depth.

[1] ‘The Late Rev WWF Murray, MA’, Church News, October 1894, p.156; Whitfield Index (LINC Tasmania, Launceston)

[2] The Tasmanian Pioneers Index records that William Wallace Fullarton Murray senior and Louisa Augusta Schaw married at Richmond, Tasmania, in 1851 and produced five children at New Norfolk, Louisa Augusta Murray (born 1854), Mary Wallace Murray (born 1857), Eleanor Carter Murray (born 1859), then the two boys. William Wallace Fullarton Murray junior’s birth, recorded without given names, was 23 April 1861 (RGD33, 1664/1861). Thomas Charles Murray was born 5 October 1862 (RGD33, 1188/1862). However, the author of ‘The Late Rev WWF Murray, MA’, Church News, October 1894, p.156, records that he was survived by six girls, two of them married, and two unmarried sons.

[3] Valentia Kate (Kate Valencia) Murray (died 1948) married William Wilbraham Ford at Hobart in 1897, registration no.270/1897. For Ford as Smith’s grub-staker, see ‘A Balfour mining case: decision reserved’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 August 1910, p.2.

[4] For WW Ford as promoter, see ‘Mt Balfour Copper Mines’, Circular Head Chronicle, 15 April 1908, p.2, in which Ford invites the newspaper’s reporter to the mining field as a guest of the Murray brothers.

[5] ‘A Balfour mining case: decision reserved’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 August 1910, p.2. For William and Tom Murray’s gold leases, see Queenstown Assessment Roll for 1908, Tasmanian Government Gazette, 15 October 1907, p.1504. Tom Murray was then the owner/occupier of a cottage in Peters Street, Queenstown (p.1497). The Tasmanian Post Office Directory for 1907 (p.437) and 1908 (p.439) lists both Murrays as ‘mine owner, Queenstown’, whereas the 1909 edition (p.417) has them both as ‘mine owner, Mt Balfour’.

[6] ‘A Balfour mining case: decision reserved’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 August 1910, p.2. In 1910 the Court of Mines adjudicated that Smith’s one-fifth share now belonged to Ernest Plummer and James Loftus Wells of Stanley (a one-tenth share each), to each of whom Smith had sold half his interest before he disappeared (‘Murray’s [sic] Reward Mine: Balfour mining action’, Circular Head Chronicle, 31 August 1910, p.2). A Murray brothers appeal to the Supreme Court in 1911 overturned this decision, denying Plummer and Wells any interest in the Murrays’ Copper Reward mine (‘A mining dispute: the Murray Reward claim: judgment for defendants’, Circular Head Chronicle, 3 May 1911, p.2).

[7] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 13 July 1910, p.3.

[8] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 26 October, p.3; and 4 November 1911, p.2.

[9] See TB Moore diaries for 1908 and 1909, ZM5640 (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery [hereafter TMAG]).

[10] ‘The Balfour Railway: turning the first sod’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 May 1910, p.2.

[11] ‘Personal’, Circular Head Chronicle, 19 January 1910, p.2.

[12] ‘Social news’, Star (Sydney), 29 January 1910, p.16.

[13] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 9 February 1910, p.3.

[14] TB Moore diaries, 30 April 1912, ZM5641 (TMAG).

[15] ‘Balfour: general news’, Circular Head Chronicle, 30 August 1911, p.2.

[16] Did the maid hand the baby over to her father so that she could take the photo?

[17] The play is Heather Nimmo’s ‘Murrays’ Reward: a play in two acts’.

[18] The Circular Head Chronicle (‘Deaths at Balfour’, 6 November 1912, p.2) reported merely that Murray had ‘died suddenly’. The coroner found that Murray died of a self-inflicted ‘gunshot wound to the head … while of unsound mind’ (see SC195-1-82-13112, [TAHO]).

[19] E Payne, ‘Balfour mine’, Examiner, 19 March 1951, p.2.

[20] ‘Deaths at Balfour’, Mercury, 7 November 1912, p.4; death notice, Mercury, 20 November 1912, p.1.

[21] Will no.9043, AD960-1-34 (TAHO).

[22] The Hobart Assessment Roll for 1913 places her as a tenant in De Witt Street, Battery Point (Tasmanian Government Gazette, 8 December 1913, p.2426).

[23] ‘Out of town news’, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 March 1937, p.3; ‘Woman to receive £1000 damages’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 September 1942, p.7.

[24] For Tom’s reputed mental breakdown see, for example, Kerry Pink and Annette Ebdon, Beyond the ramparts: a bicentennial history of Circular Head, Tasmania, Circular Head Bicentennial History Group, Smithton, 1988, p.249. For Tom’s return visits to tend William’s grave, see Joan Foss, Memories of the Marrawah Sand Track (held by Circular Head Heritage Centre, Smithton). Tom Murray reportedly asked to be relieved of the management of the Copper Reward in 1913 because of ill health (‘The Balfour field’, Circular Head Chronicle, 17 December 1913, p.2).

[25] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 13 June 1916, p.3; ‘Personal’, Circular Head Chronicle, 30 June 1920, p.3; advert, Advocate, 3 May 1924, p.8.

[26] ‘Forest’, Circular Head Chronicle, 14 July 1926, p.5.

[27] ‘Deaths’, Mercury, 16 August 1938, p.1. Probate was valued at only £168, see AD963-1-3-2352 (TAHO). He was buried at Cornelian Bay Cemetery, Hobart. An Examiner correspondent later claimed that Tom Murray ‘just sold me the machinery and left’, predicting that ‘we have not heard the last of Balfour yet’ (E Payne, ‘Balfour mine’, Examiner, 19 March 1951, p.2).