by Nic Haygarth | 13/11/16 | Britton family history, Circular Head history

Annie Britton with Lorna (left) and Phil (centre) c1913. Yeomans and Co photo, Melbourne.

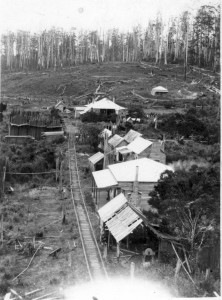

After a couple of years at Christmas Hills, in about 1912 the Brittons sold their little farm to Charlie Wells and moved to a vacant mill worker’s cottage about four kilometres away next to their mill at Brittons Swamp. This was their home for a decade as the business was established.

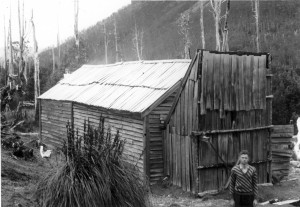

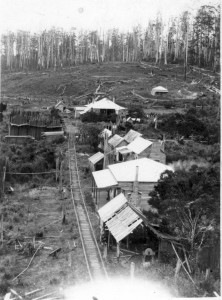

The loco shed (centre) near the mill, with the old chaff house and the hut known as Buckingham Palace to its left in the background.

The big social events of the year for people in the Christmas Hills area were the Boxing Day Picnic, New Year’s Day and, from 1923, the Easter Sports. The Boxing Day Picnic in Tommy Rowe’s paddock featured children’s foot races, tugs-of-war and a concert or theatrical performance by the kids of the school. The real competition, however, was between the ladies, trying to outdo each other with their hams, poultry and Christmas pudding spread under a huge marquee. People came in jinkers (two-wheeled carts for two or three passengers), buggies (two- or four-wheeled carriages for two people drawn by one or two horses), spring carts (two-wheeled carts without sides), on horseback or on foot. Often the road had to be cleared of fallen trees ahead of the event. No alcohol was available, but, almost as sinfully, dancing was indulged in till next morning.[1] Many a courtship began in that paddock. One young couple from Smithton set tongues wagging by disappearing hand-in-hand into the nearby forest for several hours. For kids the lolly scramble was a highlight:

Tommy Hine, the life of all picnics and parties, would take a huge tin of boiled sweets and bang loudly on the side, calling for the kids to rally round. Then he’d throw handfuls of sweets into the crowding children for them to pick up as many as they could find.

The New Year’s Day outing began well before sun-up, when Annie began to organise the whole family:

The cows would have to be milked and sent out, fowls fed, and the horse which was harnessed in the jinker and packed with our picnic basket had to be caught. The fire had to be lighted [lit], and breakfast prepared before we could start the journey to Smithton … the corduroy over the Mowbray Swamp always [being] taken at walking pace.

They had to reach Smithton by 6 am to catch Bill Boote’s motorboat down the Duck River to Seven-mile Beach.[2] Lorna remembered this as

a great adventure to us children as the boat was skillfully guided around the river’s winding watercourse. The air smelt of salt, and the water rushing by was constantly changing, colours of green and blue with white wings [being] flung up by the prow as the ship encountered opposition from the incoming tide.

When a sandbar was reached near the mouth of the river, preventing further progress, a dinghy was brought alongside the vessel to ferry the women and children ashore:

It was not an easy task for the ladies, who dressed in long frocks, but the men enjoyed helping the frightened ones (especially the pretty ones). Clasping them in their arms, they’d squeeze them more than was needed before they set them on terra firma …

The long beach was sheltered by boobyallas. AJ ‘Pelican’ Grey supplied lemonade and other cordials. He was so nicknamed because of his pelican brand lemonade bottles. These contained marble stoppers which had to be pushed into the neck of the bottle in order to release the liquid.

Sports events were held at the New Year’s Day picnic. One year when he was eleven or twelve Phil had a go at the foot running.

I had some bigger boys to compete against, but I came in first, to the amazement of others as well as myself. I seemed to have wings. The prize was only perhaps sixpence or a shilling but it was nice to beat the town lads who I knew only slightly. We lived in the bush with little or no contact with town life.[3]

Lorna remembered a small disaster that befell Annie one year on Seven-mile Beach:

One year Mother was dressed in a beautiful white dress, full length, nipped in at the waist with a waistband. She was wearing a beautifully engraved watch suspended from a gold chain around her neck. It was slipped into the waistband, the fashion at the time … Mother’s watch was a gift from her father, I think, and the pride and envy of many women … someone said to her, ‘There’s something on your neck’.

Mother, thinking in alarm that it could be a spider, rose quickly to her feet and banged her neck area. The watch broke loose and disappeared in the sand and, even with no effort spared, we failed to find it. Mother was inconsolable and, taking us with her, went for a walk along the beach to find shells which were pretty, as well as some to take home for the fowls (shell grit) in a bag. She also got a leech on her leg, a huge one. To get it off she pulled at it and, being full of blood, it burst, and her beautiful white dress was in a horrible state.[4]

Bringing home the meat

The link with the outside world was maintained by Phil and Lorna, who operated the ‘pony mail’ on Ante, a sturdy pony ‘black as coal’. Two or three days a week after school they collected the mail from the Christmas Hills Post Office (the Hine residence). On occasions, to fill in time while waiting for the mail to arrive, they visited the farm of Cornish immigrants the Rowe family, where Phil tasted his first Cornish pasty. Sometimes it would be 8.00 pm before Phil and Lorna arrived home:

The people who ran the carry mail service were wonderful to us, and would give us food and drink, and even bed us down for the night if they considered we were in danger of falling trees in a wind storm. One day the man of the house loaded us up with the usual meat load and any other provisions—two sugar bags tied together and slung over the pony’s neck as evenly as possible—and tossed us up behind, and I heard him say ‘Jee! Those Britton kids are tough. It’s as black as your hat outside.’ But we had Ante and, as he knew all the little side-tracks to avoid deep mud holes in the road, we were not very scared. The occasional branch or tree falling or a native animal jumping across the road (in my imagination only, perhaps) would make me shudder and cling more tightly to Phil up front.

There would be stops to open gates and deliver parcels, and sometimes they would take the shorter route down the tramway which, however, was dangerous in wet weather when the line might be submerged by water. A clever pony made them feel more secure:

I’ve known Ante to place his feet on the timber rails to avoid holes in the path as he smelt his way through. Ponies are very sensitive and clever really. He could push a wire fastener off a gate, open it, and turn around so that we could reach and pull the gate shut without getting off.[5]

Parcels of meat would be secured in saddlebags, but if a parcel was dropped in the dark it would be hard to find or re-secure. On one occasion Phil rode a draught horse named Boxer to school in order to bring a large cut of beef home after school. The meat was so big and heavy that it had to be lifted up to Phil on the back of the horse and balanced in front of him. But

it was a dark wet night. I was getting near home. The road was full of little holes and wet and slippery. The horse stumbled and I lost my balance. The meat fell off in the mud … My reputation was somewhat impaired, and so I gave Aunty [Kate, the Brittons’ housekeeper at the time] the horse and she had one of the men go out and get the meat out of the mud–all in a night’s work.[6]

Like nearly all early 20th-century bush farmers, the Brittons snared wallaby, pademelon and possum for extra income and, in the case of the wallaby or pademelon, extra meat. They pegged out the skins to dry on flat boards awaiting the visit of the skin buyer.

Other marsupials were less welcome. One night a quoll got into the lean-to which housed the meat safe, and when Elijah chased it, it ran into the sitting-room where the family was gather around the fire. ‘Mother grabbed me and rushed into the bedroom’, Lorna remembered. ‘She didn’t know if it was dangerous or not, I suppose’. Elijah battered it to death while it growled at him from the top of the organ.[7] Since the animals were regarded as fowl killers, no mercy was granted them.

Lorna and Phil thought they heard the ‘cough’ of ‘hyenas’ (Tasmanian tigers or thylacines) as they rode their pony home at night, although they never saw one.[8] In about 1917 Wynyard marsupial dealer James Harrison paid £5 each for three thylacine cubs secured by the Rowe brothers of Brittons Swamp after the mother thylacine had drowned while caught in a snare.[9] Lorna recalled that the Rowes had two fireside chairs backed with ‘tiger pelts’.[10]

Phil goes to finishing school

Phil was the first to go away to school. He was a sickly child, and Annie hoped his health would benefit from finishing his education with two years at Scotch College in Launceston.[11] This promoted Lorna to the front seat on Ante for mail and parcel collection. Annie was terrified of bushfires, and it was lucky that she was away settling Phil into boarding when a fire threatened the mill and the timber stacks. Lorna was returning down the tramway from the Christmas Hills with a parcel of meat when a fire fighter hurried out of the smoky gloom.

He shouted at me, as if I were to blame, as he rushed past, ‘The swamp’s on fire and before the night you will be lucky not to be burned out’. Nevertheless I was going home, fire or no fire.

Auntie Florrie had assumed control of the kitchen, feeding the fire fighters. The meat parcel suddenly looked meagre as Florrie and Lorna prepared a meal:

Uncle Mark [Britton] had collapsed, overcome by smoke in the thickest and most dangerous area, and he was brought in to rest a while. I got him a billy can of milk and water, his favourite drink, and he was soon ready for attack again. I remember him in his own way of saying thanks—‘Ah, good, this is the best drink, better than that old tea with tannin in it’. Lighting up his smelly pipe (which was full of nicotine, if he had thought about it), he gave me a cheeky grin and disappeared into the smoky area. We didn’t get burned out, but fires smouldered for days.[12]

Annie and the Britton kids, 1921. (Left to right): Phil (in Scotch College uniform), Lorna, Ken (on Annie’s lap), Annie, Frank, Eva.

Lorna’s first ride in a motor car was in 1921, when Annie took her children to visit her retired parents at Middle Brighton in Melbourne. Phil was at Scotch College, but three-year-old Frank Lindsay Britton (born 1918) and one-year old David Kenneth Britton (known as Ken, born 1920) made the trip. From Smithton they travelled to Burnie in Joey Morton’s twice-weekly Model T Ford service:

I was terrified … and held on tightly when the engine was started and away we sped, followed by a dog barking furiously. Joey Morton said not to worry as we would soon lose it when we got around on to the straight where we could do 25 miles [40 kilometres] per hour.

The return Bass Strait crossing on the Marrawah, the tiny Holymans steamer, filled both Lorna and Annie with apprehension. Annie was a poor sailor. Lorna thought, ‘Well, I’ll be able to help with the children anyway’, but soon both were seasick. Frank was sick on the toilet floor, whereupon, as Lorna recalled,

The stewardess, a harsh-tongued woman, shouted at me to clean it up, but as I had nothing excepting the toilet paper to do this I grabbed Frank and quickly retreated to our stuffy cabin.

Fresh air and calmer seas revived the Brittons next day, enabling them to watch the stevedoring work at King Island. Through the afternoon they passed Hunter and Three Hummock Island, and in the evening a full moon provided a silvery path to Stanley, where the ship berthed beneath the huge grey-black rock of the Nut. There was time next morning to explore the tiny town before Tommy Hine picked the family up with his fancy double-seated buggy and pair of lively horses. Back at Christmas Hills, Elijah had freshened up the cottage with the first spring bulbs—golden daffodils, eggs and bacon and tiny snowdrops. ‘It was so lovely’, Lorna remembered, ‘that tears filled my eyes, realising also that we were “home”!’ It was, however, only a temporary home. The permanent one at the mill was two years away.

Meanwhile, Phil remembered his two years at Scotch College (1920–21) as

the best years of my life. I was able to get out of the bush for a while and the Launceston air was good for my health, besides all the friends I made and learnt to play sport as well was education.[13]

Phil was missed at Scotch when he left. In February 1922 his friend Viv wrote from the school to say that the boys had a holiday in honour of Princess Mary’s birthday:

Dear Old Phip [sic]

I wish you were back here now. I miss you terrible much.

Davvy and I went rabbiting yesterday we saw 5 rabbits but we didn’t get any … I lost my fount-pen for about 5 minutes yesterday. It dropped in the river and when I found it only the top was to be seen. In another 2 or 3 minutes I reckon it would have sunk…

Love from Viv

PS Davvy and I went rabbiting to-day and we caught two. We are going to have them for breakfast to-morrow.

Shack sends his love to you[14]

A month later Les Acheson wrote, delighted that Youll from ‘Grammar’ might be joining Scotch College and that ‘Fordy’ might return to the school, increasing its chances of winning the cricket premiership.

There are a good few new chaps this term but nearly all nippers. I am in the 3rds at cricket. I suppose you drive the loco about.[15]

Phil wasn’t the loco driver, but there was plenty to keep him busy. Returning after those two years in Launceston, his first job was to fell all the dry trees which threatened to fall on the house, keeping Annie in a state of anxiety. Phil had ceased to be known by his second name, Raymond, while he was at Scotch. Now, as his sister Lorna recalled, the same change happened at home:

I considered ‘Ray’ was much too sissy for such a tree killer and he should be called by his first name. So he became Philip or Phil—Philip Raymond.[16]

[1] ‘The Holidays: In the Country: Christmas Hills’, Examiner 29 December 1916, p.6.

[2] Phil Britton notes, p.16.

[3] Phil Britton notes, pp.16–17.

[4] Lorna Britton notes 1983, pp.47–48.

[5] Lorna Britton notes 1983.

[6] Phil Britton notes, pp.14–15.

[7] Lorna Britton notes, 1983, pp.12 and 24; Phil Britton notes, p.11.

[8] Lorna Britton notes, 1983, p.23.

[9] ‘Proof of a tiger tale’, Advocate, 25 August 1977.

[10] Lorna Britton notes, 1984, p.23.

[11] In 1920 Phil Britton topped the Scotch College Fourth Form in Scripture (‘Scotch College Annual Speech Night’, Examiner 13 December 1920, p.3).

[12] Lorna Britton notes 1984.

[13] Phil Britton, Memories of Christmas Hills (Brittons Swamp), p.17..

[14] Viv to Phil Britton, undated (probably 27 February 1922).

[15] Les Acheson to Phil Britton 27 March 1922

[16] Lorna Britton notes 1984.

by Nic Haygarth | 13/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

In May 1914 Ron Smith’s former Forth mate Ted Adams invited him to go hiking at Lake St Clair. Smith, who would be one of the major figures in the establishment of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park, could not make the appointed time.[1] He had business to attend to at Cradle Valley, but perhaps when that was done a cross-country short-cut would bring them together. ‘I thought … I could go overland to Lake St Clair to meet you there’, he told Adams.[2] It was perhaps in that instant that Ron Smith conceived the idea of the Overland Track between Cradle Valley and Lake St Clair. Ironically, it would take him another 27 years to walk it.

The opportunity finally came in late December 1940. Now fifty-nine years old and an invalid pensioner as the result of World War I service, Smith was also the secretary of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board, a land owner at Cradle Mountain and the major documenter of the area’s European history, flora and fauna. The Overland Track, the southern section of which was roughly marked by Bert Nichols in 1931, had only become suitable for independent travellers in 1935–36 after additional track and hut work by Nichols, Lionel Connell and his sons.[3] Few people had then taken up the challenge of tramping a track that now attracts about 10,000 per year from all over the world.

Ron’s early trips from his home at Forth to Cradle Mountain were accomplished on bicycle and on foot, with stopovers at Middlesex Station, but in 1940 he was able to drive from his new home at Launceston to Waldheim Chalet, Cradle Valley, in less than five hours. From 1925 to 1936 the Smiths had had their own house at Cradle Valley, and they would have one again, Mount Kate house, from 1947.[4] However, in 1940 they were content to stay in the late Gustav Weindorfer’s Waldheim Chalet, then managed by Lionel and Maggie Connell. In fact it was almost a second home for the Smith family, since Ron’s oldest son, whom he called Ronny, and Kitty Connell, daughter of Lionel and Maggie, were courting. And yet, despite the stringencies imposed by the war raging in in Europe, people continued to enjoy the major holiday period of the year. On Christmas Day 1940 Waldheim was bursting at the seams with hikers, 50 guests in all. What a peaceful Christmas for head chef Maggie Connell! Ron slept on a sofa in the dining room, his sixteen-year-old son Charlie on the floor of the same room.

Ron Smith was always a formidable record keeper, and in his diary he recorded with typical precision that he and Charlie were on their way at 7.38 next morning, each of their knapsacks weighing 40 lbs (18 kg). After regular bouts of illness, Ron possibly doubted his own endurance. Two fit young men, Wally Connell and Ronny Smith, carried those heavy packs up to Kitchen Hut, sparing the hikers the full rigours of the tough climb up the Horse Track. After breakfast, Ron and Charlie continued alone, being passed by a party of five women who had started from Waldheim after them. Kitchen Hut was then only a three-sided shelter. There was no proper hut between Waldheim and Lake Windermere, making day one of an Overland Track trip a long and potentially dangerous one. Ron and Charlie reached Waterfall Valley before meeting their first fellow hikers—two young Sydney men—walking in the opposite direction (from Lake St Clair to Cradle Mountain, now prohibited).

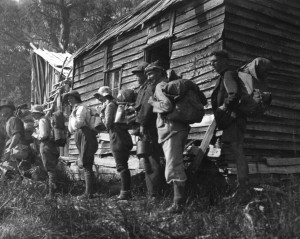

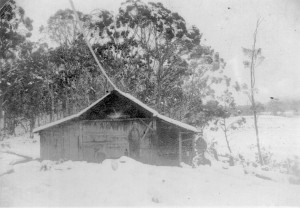

The old miners’ hut at Lake Windermere, 27 December 1940. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

A Fred Smithies shot showing the rest of the old Windermere Hut, taken during an Overland Track tramp. Courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

Father and son reached the Connells’ new Windermere Hut at 4.23 pm, nearly nine hours after setting out from Waldheim. The party of five women camped outside, leaving the hut to the men—and two grey possums, which entered, in what became Windermere tradition, via the chimney in their quest for food. Next morning, Ron and Charlie visited the c1901 Windermere miners’ hut, now in ‘great disrepair; the chimney fallen down and the roof very leaky’. Ron had reached the old hut with Gustav Weindorfer in 1911 and 1914; it was the furthest south he had so far travelled on the route of what became the Overland Track.[5]

Day two, from Windermere along the watershed of the Forth and the Pieman, then around the Forth Gorge and through to Pelion Plain, was another tiring one. They boiled the billy for lunch on the edge of the forest at Pine Forest Moor, with the dolerite ‘organ pipes’ of Mount Pelion West looming large ahead of them. At New Pelion Hut they re-joined the party of five women, greeted a married couple called Calver who arrived from Lake St Clair, plus four Victorian men who were returning to Waldheim after climbing Mount Ossa. There were ten in the Connells’ new hut, which had two rooms so that men and women could be separated. For Ron every new meeting was noteworthy. Names and sometimes addresses were exchanged, and it was a chance to chat and learn. The leisurely experience was far removed from that of more recent times, when the two-way traffic could make the Overland Track feel rather like a scenic Hume Highway.

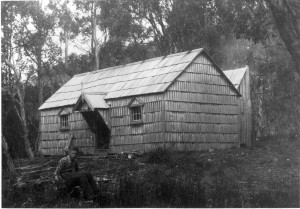

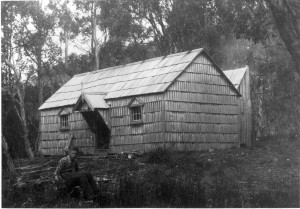

Flourishes of Federation Queen Anne and Arts and Crafts architecture in the Connells’ King Billy pine shingle New Pelion Hut, 28 December 1940, Charles Smith in the foreground. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

With rain threatening, the Smiths decided to spend a day close to shelter at Pelion. Ron had now ventured further south than his departed friend, Gustav Weindorfer, who had taken the census at the Pelion copper mine and climbed Mount Pelion West in April 1921.[6] The mine manager’s hut (Old Pelion) and the workers’ hut from that period were both in good repair. Leaving these huts, Ron and Charlie crossed Douglas Creek and followed the southern edge of Lake Ayr until they met the Mole Creek (Innes) Track near the rock cairns and poles marking the then Cradle Mountain Reserve’s eastern boundary.

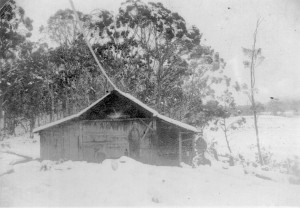

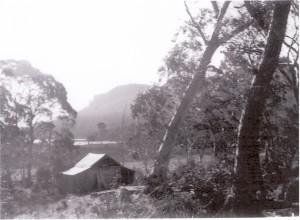

Tommy McCoy’s hunting hut near Lake Ayr. Photo courtesy of the McCoy family.

McCoy’s hut as it looked in 1951, with Mount Oakleigh and Lake Ayr for a backdrop. Photo courtesy of the McCoy family.

The reserve had been a bird and animal sanctuary since 1927. Yet, cheekily poised about 250 metres beyond the boundary, Tommy McCoy’s new hardwood paling hunting hut made his intentions clear. Hobart hikers would become conservation activists, puncturing McCoy’s food tins with a geological pick, when they came across his hut in 1948.[7] However, the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary, a former possum shooter and a man of a different ilk, was much more respectful, leaving payment of threepence for a candle he removed from McCoy’s camp. Ron and Charlie also inspected the old post-and-rail stockyard near the western end of Lake Ayr on their way back to New Pelion. On their second night at Pelion propriety was dispensed with, as the Smiths and Calvers shared a room, leaving the other room for newcomers.

An unsympathetically cropped image of the two-room Du Cane Hut, 29 December 1940, with Cathedral Mountain omitted but Charles Smith in the foreground. Ron Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

An earlier Ray McClinton or Fred Smithies shot of the original one-room Du Cane, taking full advantage of the view of Cathedral Mountain.

The party of five women motored past the Smiths on the climb up to Pelion Gap next day, marching right through to Narcissus Hut, a distance of about 27 km in a day. Ron and Charlie took a leisurely pace, visiting Kia Ora Falls and camping at Du Cane Hut (Windsor Castle or Cathedral Farm), Paddy Hartnett’s old haunt, which had been converted to a two-room building in keeping with New Pelion. Reflecting, perhaps, his reduced stamina, Ron elected to wait on the main track while Charlie viewed Hartnett Falls. The pair also made a diversion to Nichols Hut, the walkers’ hut Bert Nichols had erected beside his old hunting hut. For a man who in his younger days rarely left a bush setting or bush person unsnapped, Ron Smith was relatively parsimonious with his photos on this trip, neglecting these buildings, McCoy’s hut and the old Mount Pelion Mines NL huts. He appears to have been ignorant of the other hunters’ huts located near the track between Pelion Plain and Narcissus River.

Ron and Charlie were accompanied most of the way from Pelion to Narcissus Hut by the Robinsons, a Sydney couple they had first met at Waldheim. Crossing the suspension bridge over the Narcissus River, Mrs Robinson’s hat landed in the drink and disappeared, despite a group rescue effort. Narcissus Hut, the staging post for the motorboat trip down Lake St Clair, as it is today, replicated the situation at Waldheim, being full to the brim and beyond, with numerous tents being pitched outside. Among the hikers were the economist and statistician, Lyndhurst Giblin, and HR Hutchinson, Chairman of the National Park Board, the subsidiary of the Scenery Preservation Board which oversaw the Lake St Clair Reserve. Indeed, it must have seemed like the veritable busman’s holiday when the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary met the Lake St Clair Reserve Board chairman on the Overland Track that united their realms.

Bert Fergusson’s motorboat loading at Narcissus Landing, 31 December 1940. Seventeen to board, including the party of five women, and a tentative Charles Smith (fourth from right). Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The trip was concluded in six days. It took 1 hour 45 minutes to traverse Lake St Clair in the famous Bert ‘Fergy’ Fergusson motorboat on New Year’s Eve, 1940. This seems extraordinarily slow progress—didn’t Paddy Hartnett row the lake faster than that 30 years earlier, against the wind?— until you realise how overloaded Fergy’s vessel was! Seventeen people were crammed aboard what was certainly not Miss Velocity. Ron and Charlie slept in Hut Twelve of Fergy’s tourist camp at Cynthia Bay, where a housekeeper, Mrs Payne, was also employed. From here Fergy operated a free ‘bus’ service (Jessie Luckman called it a ‘frightful old half bus’ sporting sawn-off kitchen chairs with basket-work seats) to Derwent Bridge, where the departing tourist joined one of Grey’s buses. The Lake St Clair tourist infrastructure of 76 years ago was surprisingly well organised. Charlie having departed with family members, Ron stayed on a day more and caught a bus back to Launceston via Rainbow Chalet at Great Lake and Deloraine, using a short stopover in that town to submit a butcher’s order for Fergy. All this recreational transport at a time when petrol was rationed for the war effort!

On 3 January 1941 Ron Smith rested at home, having at last completed the journey contemplated 27 years earlier. Perhaps the experience strengthened his belief in the need for a motor road from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair, thereby conferring universal reserve access.[8] Age may not have wearied him, but maybe at that moment his swollen right foot felt more comfortable on an accelerator than in a heavy boot.[9]

[1] See ‘Ron Smith: bushwalker and national park promoter’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.132–59.

[2] Ron Smith to GES Adams, 15 May 1914, NS234/17/1/4 (TAHO).

[3] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men, pp.122–27.

[4] See ‘Smith huts’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.36–43.

[5] For the 1911 trip, see Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 29 November and 1 December 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO). The pair’s arrival at the Windermere Hut in 1914 had scared the life out of its incumbent, miner/hunter Mick Rose, who feared he had been he had been nabbed engaging in out-of-season snaring.

[6] Gustav Weindorfer diary, NS234/27/1/8 (TAHO); ‘Mountain beauties: Tasmania’s charms’, Examiner, 6 January 1934, p.11.

[7] Interview with Jessie Luckman.

[8] See, for example, minutes of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board meeting, 25 June 1947, AA595/1/2 (TAHO).

[9] This account of Ron and Charlie Smith’s walk on the Overland Track is derived from Ron Smith’s diary, NS234/16/1/41 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 11/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

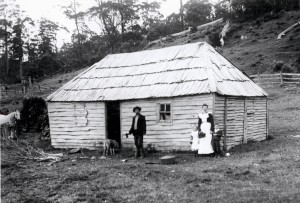

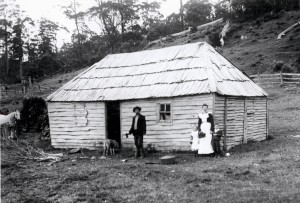

In Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, written with Simon Cubit, I told the story of a visit made to the Browns’ hut at Middlesex Station by the Anglican Bishop of Tasmania, Henry Hutchinson Montgomery and the Vicar of Sheffield, JS Roper, in February 1901.[1] Montgomery’s photo of the Brown family at their hut, featuring an eighteen-year-old Linda Brown with already two children, and the family turned out in Sunday best for the camera, tells us much about their isolated lifestyle, their social expectations and their pride.

Henry Montgomery’s photo of Field stockman Jacky Brown and his wife Linda Brown at their hut, with children Mollie (the babe in arms) and William (standing with his father). The girl standing beside Linda is possibly from the Aylett family and fulfilling the role of maid. PH30-1-3836 (TAHO).

The underlying story in this photo is the decline of the Field grazing empire, which was becoming as rickety as the Middlesex hut. That empire had been established by ex-convict William Field senior (1774–1837) and his four sons William (1816–90), Thomas (1817–81), John (1821–1900) and Charles (1826–57). The death of John Field of Calstock, near Deloraine, in the previous year had closed those generations which had spread half-wild cattle from the Norfolk Plains/Longford area as far as Waratah, intimidating other graziers and dominating its impoverished landlord, the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co). The Fields were notorious for occupation by default, and they knew that legitimately occupying the VDL Co properties of the Middlesex Plains and the Hampshire and Surrey Hills would also allow them to occupy all the open plains of the north-western highlands gratis. The Fields’ power over the VDL Co increased as the company’s fortunes declined. In 1840 the Field brothers leased the 10,000-acre Middlesex from the VDL Co for 14 years at £400 per annum.[2] In 1860, after financial losses forced the VDL Co to retreat to England as an absentee landlord, they obtained a lease of the Hampshire and Surrey Hills plus Middlesex—170,000 acres in all—for the same price, £400.[3] The problem for the VDL Co was that few other graziers wanted such a large, isolated holding, and that any who did dare to take it on would have to first remove the Fields’ wild cattle. In 1888 the Fields screwed the VDL Co down further to £350 for the lot for the first two years of a seven-year lease, raising the price to £400 for the final five years.[4]

Nor were any of these negotiations straightforward. With every lease there was a battle to collect the rent, necessitating letters between the respective solicitors, Ritchie and Parker for the VDL Co, and Douglas and Collins for the Fields. Thomas or John Field would stall, demanding a reduction in rent for fencing, rates or police tax. On one occasion they requested the right to seek minerals, and to make roads and tramways on the leased land—and to take timber for the construction of this infrastructure.[5] Worse yet, in 1871 some of Fields’ wild cattle from the Hampshire or Surrey Hills got confused with VDL Co stock and ended up on the Woolnorth property at Cape Grim, and the VDL Co couldn’t figure out how to get rid of them.[6] Since Fields would soon ask to rent Woolnorth—and be refused—it was as if their advance guard had infiltrated the property ahead of a storming of the battlements.[7] The VDL Co’s solicitor told them that to shoot the offending animals would be to risk a Field law suit, leaving the company no option but to buy them from Fields and then weed them out for slaughter.[8]

However, now things were changing. By the 1890s reduced meat prices and natural attrition had taken their toll on the Field empire. John Field was the only one of the four brothers still standing. The VDL Co was now fielding offers from potential buyers of the large Surrey Hills block, as the company looked to land sales and timber for financial redemption. John Field’s final gesture in 1900 was to offer the VDL Co £75 per year for Middlesex.[9] The VDL Co wanted £125, and in the new year of 1901 the executors of John Field’s estate haggled for a concession. They wanted their landlord to offset some of the increased rental by paying for improvements to the station. ‘The place is greatly out of repair and the house would require to be a new one throughout’, WL Field told VDL Co local agent James Norton Smith. ‘The outbuildings are none and there is not a fence on the place’.[10]

We can see for ourselves that some of this, at least, was true. The unfenced, out-of-repair Middlesex ‘house’ in Montgomery’s photo had already undergone renovations, a chimney having been removed from its eastern end. However, Field was probably exaggerating a little. Perhaps there were no outbuildings, but Fields probably always kept a second hut at Middlesex for the stockmen who came up for the muster.

Silence spoke for the VDL Co. Receiving no reply to his request, WL Field agreed to the annual rental of £125 for seven years, with an option of seven years more at £150 per annum, noting that ‘we have the 10,000 acres of govt land adjoining it at a rental of £60 and I consider the block as good as the co’s and it will save a lot of fencing having both …’.[11]

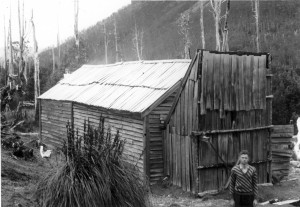

The Middlesex Station huts in February 1905, with Jacky, Linda Brown and two children standing in front of the second (mustering) hut. The hut occupied by the family can be seen at the extreme left in the left-hand photo, set well away from the others. The curl of smoke from the distant hut confirms the location of the chimney at its rear.

Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

A close-up of the Browns in front of the mustering hut. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

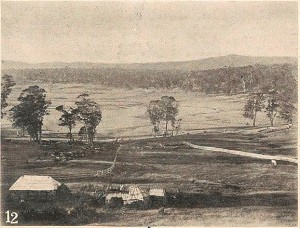

Perhaps the VDL Co did eventually submit to improvements. By 1905, when Jacky and Linda Brown were still in residence, there was a collection of buildings at Middlesex Station, including a ramshackle hut with a boarded-up window which was used by mustering stockmen and travellers. The main hut used by the Browns was set further east, away from these buildings, outside the House Paddock, which had now been fenced.

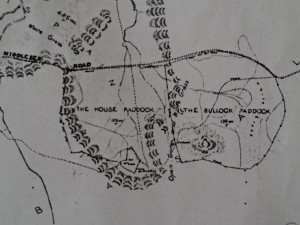

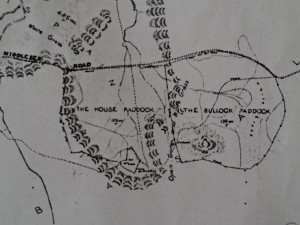

However, on the down side, the Fields were losing their unfettered reign over the highlands. A small land boom occurred in the upper Forth River country when a track was pushed through from the Moina region to Middlesex. The Davis brothers from Victoria tried to cultivate the Vale of Belvoir, and highland grazing runs were selected.[12] Frank and Louisa Brown were Fields’ Middlesex residents in November 1906 when Jack Geale, the new owner of the Weaning Paddock, asked new VDL Co agent AK McGaw to pay half the cost of fencing the eastern side of the Middlesex block, which would enable him to separate his herd from the Fields’.[13] McGaw sent surveyor GF Jakins with a team of men to Middlesex to re-mark the boundaries. The resulting survey shows the fenced paddock, the collection of buildings and the separate stockman’s hut.

A crop from GF Jakins’ 1908 survey of the Middlesex Plains block, showing the House and Bullock Paddocks and the collection of buildings at the head of the House Paddock. From VDL343-1-359, TAHO, courtesy of the VDL Co.

Jakins also marked Olivia Falls (‘falls 300 ft’, ‘falls 60 ft’)—better known today as Quaile Falls—just outside the south-east corner of the Middlesex block. This casts doubt on the story of Quaile Falls being discovered by Roy Quaile while searching for stock.[14] The falls were probably known to the miners who worked the Sirdar silver mine nearby in the Dove River gorge from 1899—and were possibly given their present name in recognition of Wilmot farmer Bob Quaile’s visits there with tourists.[15] And what did the Aborigines call this ‘second Niagara’ long before that?

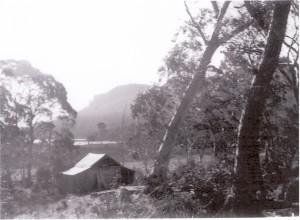

Perhaps it was knowledge of the ‘red’ pine growing on the south-western corner of the Middlesex Plains block that prompted Ron Smith of Forth to enquire about buying the block from the VDL Co.[16] That land owner would have enjoyed this attention. In 1908 Fields signed up for their second seven-year lease on Middlesex, at the increased rental of £150 per year. They had to agree to allow the VDL Co to sell any part of the Middlesex Plains block during that term excepting the 640 acres around the ‘homestead’.[17] As a regular visitor to Middlesex Station on his way to and from Cradle Mountain, Smith had no illusions about the standard of accommodation provided there. In January 1908 he and his party stayed in a new hut that had been built for the mustering stockmen. ‘We were very glad to do so’, Smith noted, ‘as the old hut was very much out of repair … ‘ It was a two-room hut with a moveable partition, so that it could be converted into one room as needed.[18]

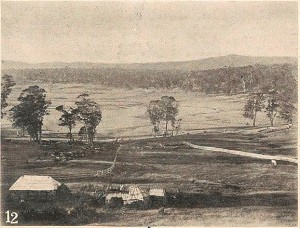

A collection of Middlesex buildings in December 1909 or January 1910. These seem to be the same buildings visible in the 1905 photo. The main hut further east is not shown here. Ron Smith photo from the Weekly Courier, 22 September 1910, p.17.

Louisa Brown with a pet wallaby, January 1910. This appears to be the same main hut photographed by Montgomery in 1901. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

By December 1910 that hut was also in a state of disrepair. The Fields asked the VDL Co to renew or extend the two-roomed hut in time for the muster in the following month: ‘Up to now they have lived in the old house, but it is really unsafe. Mr Sanderson [VDL Co accountant] has seen the house that was built by us about four years ago, as he was there and stayed in it just after it was built. There is a man living there [Frank Brown] who would split the timber & do it’.[19]

Main hut at Middlesex Station, Christmas 1920. The figure second from right appears to be Dave Courtney, with moustaches but as yet no beard.

Ray McClinton photo, LPIC27-1-2 (TAHO)

Such is the incomplete photographic record of Middlesex Station at the time that it is unknown whether the mustering hut was replaced. However, we can say more about the main hut used by the stockman. The hut shown in the 1901 and 1910 photos appears to have remained the stockman’s hut in 1920 when Ray McClinton snapped it, this time with Dave Courtney the resident stockman. The chimney had been rebuilt with a vertical arrangement of palings, and a skillion had been added at the back. A prominent stump standing beside the hut in this photo must have been just out of picture in Montgomery’s 1901 shot.

After Fields had rented Middlesex from the VDL Co for 82 years, in 1922 JT Field, son of the late John Field of Calstock, bought the block, ending the uncertainty about its future. However, the lone figure of 49-year-old stockman Dave Courtney was emblematic of the Fields’ dwindling presence in the highlands, and his long, flowing beard of the 1920s and 1930s would not have allayed the impression of a once vigorous enterprise slowly grinding to a halt.

[1] Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.24–29.

[2] Edward Curr, Outward Despatch no.215, 18 November 1840, VDL1/1/5 (TAHO).

[3] Inward Despatch no.291, 16 November 1857, VDL 1/1/6 (TAHO).

[4] Minutes of VDL Co Court of Directors, 16 February 1888, VDL201/1/10 (TAHO).

[5] Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 16 April 1875, VDL22/1/5 (TAHO).

[6] John Field offered to settle the matter by selling the wild cattle to the VDL Co for £100. See Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 7 July 1871. See also Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 14 October 1871 and 3 September 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[7] Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 16 February 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[8] Ritchie & Parker to James Norton Smith, 31 October 1871, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[9] Minutes of VDL Co Court of Directors 3 October 1900, VDL201/1/11 (TAHO).

[10] WL Field to James Norton Smith, 19 January 1901, VDL22/1/32 (TAHO).

[11] WL Field to James Norton Smith, 30 April 1901 and 15 June 1901, VDL22/1/32 (TAHO).

[12] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.18–23.

[13] JW Geale to EK McGaw, 26 November 1906, VDL22/1/38 (TAHO).

[14] Leonard C Fisher, Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Port Sorell, 1990, p.150.

[15] See, for example, ‘The Cradle Mountain’, Examiner, 5 January 1909, p.6.

[16] AK McGaw to Ron Smith, 23 January 1905, NS234/1/18 (TAHO). The term ‘red pine’ was often used indiscriminately to describe both the King Billy (Athrotaxis selaginoides) and pencil (Athrotaxis cupressoides) pine timber.

[17] WL Field to AK McGaw, 24 September 1908, VDL22/1/40 (TAHO).

[18] Ron Smith, ‘Trip to Cradle Mountain: RE Smith and the Adams Brothers, January 1908’, in Ron Smith, Cradle Mountain, with notes on wild life and climate by Gustav Weindorfer, the author, Launceston, 1937, pp.67–77.

[19] WT and JL Field, writing on behalf of WL Field, to AK McGaw, 7 December 1910, VDL22/1/42 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 06/11/16 | Britton family history, Circular Head history

‘Manuka’, originally known as ‘Glen Valley’, was built by Elijah Britton for his family at Brittons Swamp, with the help of his cousin Fred Britton and a plumber, Jack Bailey. The blackwood and hardwood for the inside walls and floors were air-seasoned, then dressed with a steam planer. Elijah’s one failing was brickwork, his chimneys leaving much to be desired. Nevertheless, in April 1922 the house was christened:

The seven-roomed 1922 bungalow ‘Glen Valley’, with the steam sawmill in the background at left, and the loco shed to the right.

‘Glen Valley’ with lattice added to the veranda and the garden further developed.

HOUSE-WARMING. — Mr E Britton has built a spacious residence at Christmas Hills. On Easter Saturday night the residents wended their way to give Mr and Mrs Britton a house-warming. A very pleasant evening was spent and cheers were given for Mr and Mrs Britton. During the evening items were rendered by Mrs P Streets, Miss E Dunn, and Messrs S Rowe, O Murphy, T Hine, A Rowe, R Dunn, and E Rowe. Excellent music for the dancing was supplied by Mr Y Wilson. Mr P Streets very capably carried out the duties of MC.[1]

View from the chimney of the original sawmill, showing the blacksmith’s shop (foreground), workers’ cottages (middle distance) and the Britton family house (background). The tramway pictured was used to supply wood to the house. The Bass Highway would later separate ‘Manuka’ from the other buildings.

This was long before electricity or sewerage came to the bush. The toilet was a kerosene tin in a little hut behind the house. Once or twice a week the kerosene tin was emptied, the effluent being buried in a hole.[2]

The mill workers’ cottage vacated by Elijah’s family became Mark Britton’s quarters, where he slept and did the office work. Once a year Lorna washed his blankets and scrubbed his dirty floors. Mark was in the habit of piling bark, sticks and firewood against the inside wall of his office. ‘This was clean dirt, so I’d take that out and scrub that room, but the bedroom was the worst’.

‘Our home was his real home’, Lorna remembered. ‘He had his special place at the table and sat one side of the fireside of an evening in the lounge chair opposite Father all the years he lived with us’.[3]

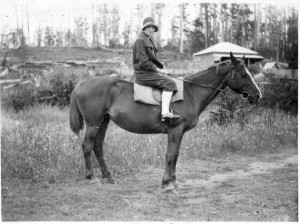

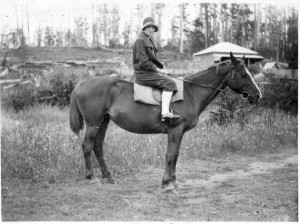

Lorna Britton leaving for a painting lesson on the ‘scary’ light chestnut draughthorse Boxer. She wrote that this horse was ‘so skittish he could toss me off his back easily, but boy could he trot. On the way to Smithton with the drains on each side of the Mowbray Swamp, it was a nightmare to have this scary horse. A passing car could make him jump sideways and you’d end up in the huge drain’. In the background is the cottage behind ‘Manuka’ which was used by workers at the mill, and in which Philip and Maria Britton also stayed.

An unusual shot of a middle-aged Annie Britton smiling.

Right from the start, Annie had recognised the need to diversify and, especially that farming, as well as timber, was needed to sustain her family. Her duties in the home were so many and so laborious that she was run off her feet. Even as her children were growing up and leaving home, Annie suffered with quinsy and a sore throat. She had her tonsils removed late in life in hope of fixing the latter problem. During the winters, her seasons of greatest suffering, the burden of the housework and childcare fell upon her eldest daughter Lorna:

Mother was either too sick or too busy to give the children much love, and I lavished all my affection on those kids. I never knew Mother to be affectionate to me or Phil, and we missed out there.

I was amazed to hear someone say they didn’t know I did anything other than play the violin and piano, paint, and be a lady. Maybe I did when they knew me, but who did the helping where there was no hot water and electric power and light? I would do the last tea dishes in a dish of hot water on the kitchen table by the light of one candle, and put away the meat that came late. It had to be lightly salted and put in the meat safe in a cool place. Mother would already be in bed, and I’d still be working till 8 or 9 o’clock.

Lorna remembered the young Ken as ‘The Little Comforter’ because with a twinkle in his eye he could bring a smile to Annie’s face

He loved the farm animals and could find a calf that had strayed or been hidden by its mother, or a hen’s nest. At that time the common swear word was ‘cussed’, heavily emphasised. I never heard my father, uncle or brothers swear, so Ken came running in at the lisping stage, clutching an egg and shouting ‘I heard a dusserd hen dackle, and I runned over and bruted her off the nest’. It was a favourite saying around the mill for a long time and caused many a happy moment.

Ken Britton at six months of age in 1921.

The next-youngest boy John was ‘a frail little chap’ who developed eczema so badly that, despite medical treatment, Lorna feared his earlobes would drop off:

But he survived, and I cared for him until I was sent away to school in Launceston for one year. When I left school he was still weak and sickly, suffering many colds and Mother and I sat up more nights than I wish to remember when he had croup and we tried with limited medical care to ease his suffering.

One night he was so distressed that Mother, with her face set in anguish, left the room and brought in a spoonful of something which she poured down his little throat and soon brought relief. What it was I never really knew, but it was probably something that her mother had given her as a child. I think the mixture contained turpentine.

Both feared he would not ‘make old bones’, but John would prove them wrong.[4] Unfortunately, to do so, he would have to survive an accident in which his legs were crushed.

Lorna Britton at Broadland House, Launceston, 1923.

As Elijah and Annie’s children grew, the role of mail and meat bearers fell to Eva, Frank and Ken in turn. By that stage the house the Brittons formerly occupied at Christmas Hills had been enlarged to become the new school, and a public hall had also been raised nearby by public subscription. In 1922 the school graduated from a subsidised school to an ordinary state school, with Irene Dunn continuing as teacher.[5] It was in the unfinished school building that 15–year–old Lorna Britton was farewelled when she left for Launceston to finish her education at Broadland House Ladies’ College (now part of Launceston Church Grammar School):

Dancing was the order of the evening … a presentation of an Xylonite brush and comb and a very handsome box of writing material was made by Mr. C. Burton on behalf of the residents of Christmas Hills to Miss Britton to remind her of those she was leaving behind. Mr. Roy [sic: Phillip Raymond] Britton on behalf of his sister, thanked all for the kind wishes and the presents given to Lorna. The singing of “For she’s a jolly good fellow” terminated a very enjoyable evening.”[6]

[1] ‘Christmas Hills’, Circular Head Chronicle, 26 April 1922, p.3.

[2] Frank Britton memoir, 16 December 1992 (QVMAG).

[3] Lorna Britton notes1983.

[4] Lorna Britton notes 1983.

[5] ‘Xmas Hills Picnic Sports’, Advocate, 21 March 1923, p.6.

[6] ‘Christmas Hills: farewell’, Circular Head Chronicle, 14 February 1923, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 06/11/16 | Britton family history, Circular Head history

The dolomite swamp that took the name of the Brittons Swamp is thought to be a polje, that is, a centrally-draining dolomite sinkhole. Dismal Swamp, the selectively logged hollow now operated as a tourist venue, is an almost intact version of the same sort of feature.[1]

Beyond the basalt hills, on the dolomite swamp beyond, Mark Britton found huge stands of blackwood and saw a better future than he and his brother expected to get in the Mallee. He and Fred Oehm selected 200 acres each. Summoned over by his brother, Elijah selected 200 acres adjoining Fred’s block and which contained both hardwood and blackwood.

Phil Britton’s earliest memories of Tasmania were of arriving on the Holyman steamer the Marrawah at Burnie as a two-year-old. His sister Lorna was a babe in arms. From Burnie the family travelled by Tatlow’s horse-drawn coach south of the Sisters Hills and along the beach to Stanley, then changed coach to cross the old Sand Track over Tier Hill to Smithton.[2] Smithton had its own port at Pelican Point, from which timber was exported. Blackwood staves were already fetching a market on the mainland. On one occasion when Elijah and Harold braved the rough crossing on a timber ketch to Melbourne,

the skipper said, ‘If you blokes like to hop in and help load up these blackwood staves we will be away quicker.’ A certain Robert Pratt [junior] was also there and he did help. While Dad and Harold carried the staves on by the armful, R Pratt senior took one at a time. ‘For sure’, he said, ‘the pay will be the same’.[3]

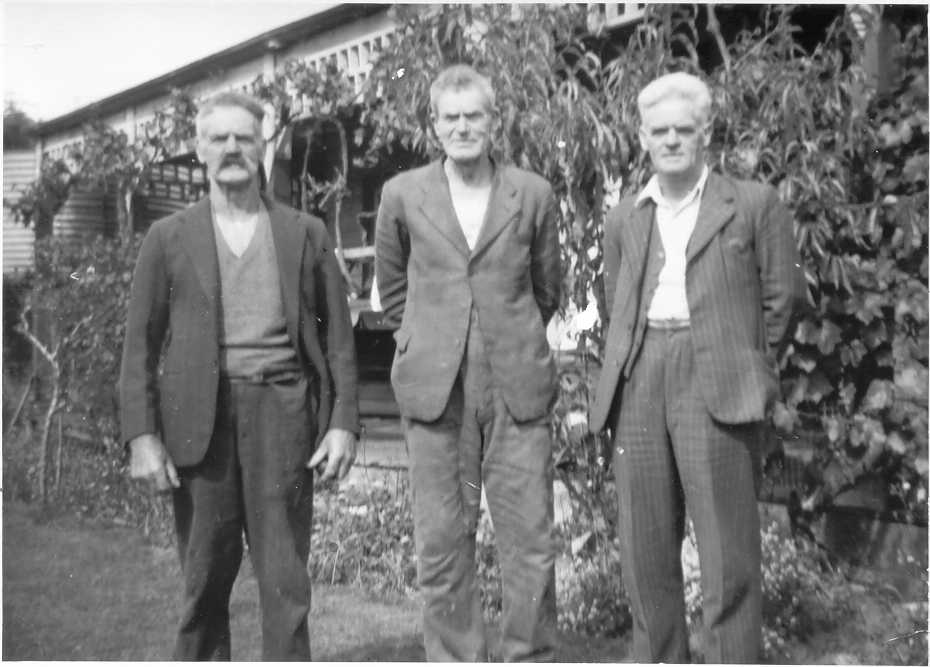

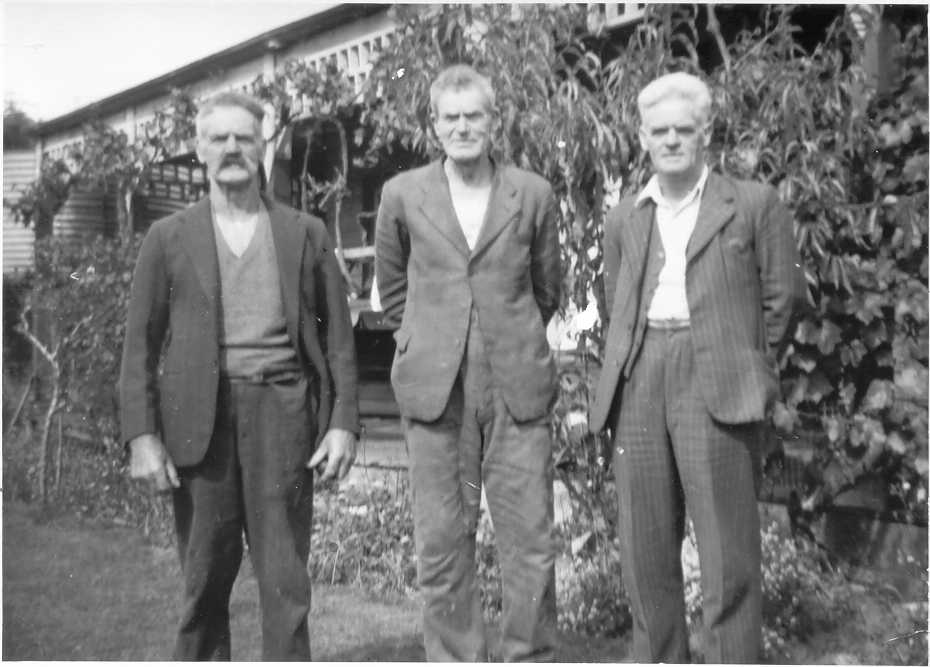

(Left to right) Elijah, Mark and Harold Britton. Twenty-year-old

Harold Britton married nineteen-year-old Laura Fixter

in 1909 and moved to Leongatha, Victoria.

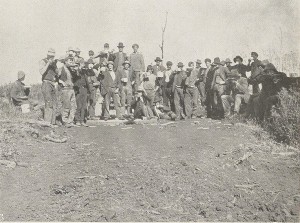

Christmas Hills State School, 1911, with five-year-old Phil Britton (arrowed) front row at left. The teacher pictured is probably Fred Parsons. The original school was a room provided by Tommy and Lizzie Hine, who also lodged the teacher and kept the post office. This was a ‘subsidised’ school, which relied upon the regular attendance of a set number of students and the community providing suitable lodgings for the teacher.

For two years the family lived in a cottage on a small acreage opposite the post office at Christmas Hills, with Elijah only coming home from the mill (four kilometres away) at weekends. While Harold Britton soon dipped out of the business, Mark and Elijah proved an ideal partnership. Elijah, a skilled, mostly self-taught blacksmith, filled the roles of engineer, saw doctor, stoker and timekeeper. He could repair anything mechanical, improvising as needed, and also manned the docker saw. Mark was a fine benchman, an expert at minimising wastage when cutting blackwood. His niece Lorna Haygarth (née Britton) recalled him even bemoaning the fate of heavy timber ends destined for the family fire:

Taking his pipe out of his mouth and putting it carefully on the hearth, he would declare, ‘What a waste, burning this beautiful wood. It should be kept and made into useful articles. Just look at the grain and lovely figure in this piece. It’s real timber, not like some of the pencil wood—it’s heavy, real heavy.’[4]

Mark was a good bullock and horse-driver and had the business brain, keeping the books. Above all, he was a positive thinker. This was essential, because the sight of a five–ton boiler being eased up the Sandhill to the Brittons Swamp site by a twelve–bullock team and a block and tackle signalled the start of a tremendous struggle for survival.

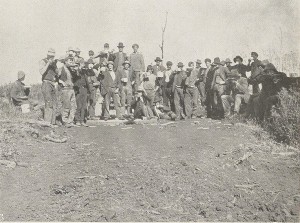

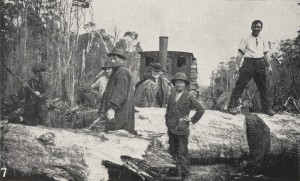

Building the Marrawah Tramway: bridging the Welcome River, 1913. From the Weekly Courier, 13 March 1913, p.20.

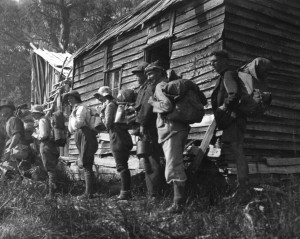

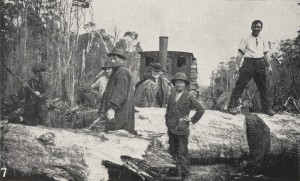

Free beer celebration for the construction party at Christmas. From the Weekly Courier, 13 March 1913, p.20

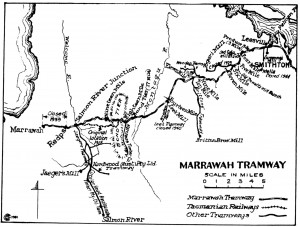

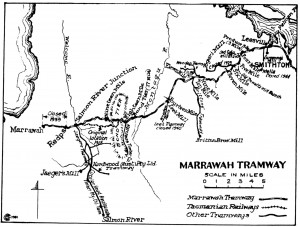

With government reluctant to build roads to bush selections, economic survival in almost impenetrable forest depended on sawmillers making their own path to market. The Marrawah Tramway (1912?–61) was started by JS Lee in order to harvest the timber on the Mowbray Swamp, epitomising the self-sufficiency and initiative of the early Circular Head sawmilling industry. The state government took over the tramway and extended it to Marrawah on the west coast. Then private timber tramways radiated from the Marrawah Tramway into the Montagu, Brittons, Arthur River and Welcome Swamps.[5]

A blockage on the Marrawah Tramway. From the Weekly Courier, 13 October 1921, p.28.

The Marrawah Tramway enters the dolomite Mowbray and Montagu Swamps on its journey from Smithton to Marrawah. Brittons’ branch tramway penetrates Brittons Swamp.

Map by ‘Wanderer’, ‘Railways and Tramways of the Circular

Head District’, Australian Railway Historical Bulletin no.168, October 1951.

Brittons’ line linked their mill to the 9¼-mile mark of the Marrawah Tramway. The 3’6”-gauge Britton Tramway cost about £2,000, a small fortune then. It originally used white myrtle spars for stringers, and was closely corded and ballasted with sawdust so that the five-horse team could haul the trucks of sawn timber (two at a time) without tripping. After a few years, heavy, long hardwood stringers were substituted for the white myrtle ones, and iron rails were placed on the outside bends. Twelve loading ramps enabled twenty-four loads of timber to be left at the junction with the Marrawah Tramway. The timber was then delivered to the Pelican Point jetty at the Duck River heads, where it was loaded on ships bound for Melbourne or Adelaide.[6]

Specialisation in blackwood, supplemented by production of hardwood and other timber, established the Britton’s seasonal regime. The swampy habitat of blackwood made haulage in the drier months essential, with strong, stoic bullocks being favoured for this task. (Horses were preferred to haul hardwood from the drier eucalypt forest.) Logging, cutting and carting in summer gave most of the men a job under cover, milling, in winter, when the weather was bad. In the winter of 1919, for example, Brittons milled about 8,000 super feet (24 cubic metres) of logs per day.

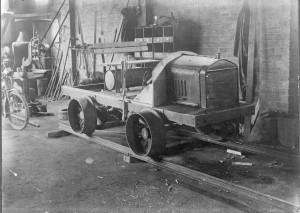

Loss of valuable horses to colic and falling trees prompted the purchase of a 1910 Buffalo and Pitts traction steam engine, which crushed culverts beneath it as it chugged from Forest to its new home. It was fuelled by the abundant wood and water. Elijah Britton devised a cog system which enabled the steam engine to be converted from road to rail, and the tramway was upgraded accordingly. The Buffalo and Pitts hauled sawn timber out to market on the tramway, back-loading with stores. When its boiler eventually rusted out, the engine was replaced by a 1904 Marshall single-cylinder traction engine, which had a better boiler and was a better steamer.

Bush engineering. The Marshall loco, seen here hauling a load of blackwood, was a triumph of improvisation.

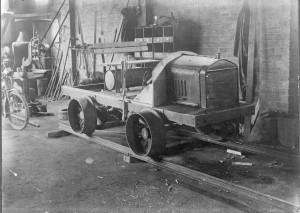

Brittons also had this Model T-Ford converted into a dynamic rail motor by Arthur Schmidt of Burnie.

Brittons’ transport problems didn’t end with delivery of timber to the Marrawah Tramway, as the following example illustrates. In 1918 Brittons reached an agreement with Cummings & Co to share the 20,000 super feet of space available on the Holyman steamer ss Hall Cain after JS Lee & Sons had loaded up their guaranteed shipment of 50,000 super feet. Brittons were to ship 15,000 super feet of hardwood to its agents in Melbourne, and delivered this timber to its junction on the Marrawah Tramway. However, timber was already stacked in the way at the junction, including seasoned blackwood owned by Cummings. This forced Brittons to load Cummings’ blackwood onto the vessel before they could load their own hardwood, leading to a dispute between the two companies. Brittons demanded and eventually gained compensation from Cummings.

[1] See Kevin Kiernan, An atlas of Tasmanian karst, Research report no.10, Tasmanian Forest Research Council Inc, Hobart, 1995.

[2] Phil Britton, ‘First Impressions of Brittons Swamp’; ‘The Britton Family’ (notes held by Britton family).

[3] Phil Britton, ‘First Impressions of Brittons Swamp’ (notes held by Britton family).

[4] Lorna Haygarth (nee Britton), ‘The Britton Story’ (notes held by the Britton family).

[5] ‘Wanderer’, ‘Railways and Tramways of the Circular Head District’, Australian Railway Historical Bulletin, no.168, October 1951, pp.151–52.

[6] Phil Britton, ‘The Britton Family’, pp.5–7 (notes held by Britton family).