The dolomite swamp that took the name of the Brittons Swamp is thought to be a polje, that is, a centrally-draining dolomite sinkhole. Dismal Swamp, the selectively logged hollow now operated as a tourist venue, is an almost intact version of the same sort of feature.[1]

Beyond the basalt hills, on the dolomite swamp beyond, Mark Britton found huge stands of blackwood and saw a better future than he and his brother expected to get in the Mallee. He and Fred Oehm selected 200 acres each. Summoned over by his brother, Elijah selected 200 acres adjoining Fred’s block and which contained both hardwood and blackwood.

Phil Britton’s earliest memories of Tasmania were of arriving on the Holyman steamer the Marrawah at Burnie as a two-year-old. His sister Lorna was a babe in arms. From Burnie the family travelled by Tatlow’s horse-drawn coach south of the Sisters Hills and along the beach to Stanley, then changed coach to cross the old Sand Track over Tier Hill to Smithton.[2] Smithton had its own port at Pelican Point, from which timber was exported. Blackwood staves were already fetching a market on the mainland. On one occasion when Elijah and Harold braved the rough crossing on a timber ketch to Melbourne,

the skipper said, ‘If you blokes like to hop in and help load up these blackwood staves we will be away quicker.’ A certain Robert Pratt [junior] was also there and he did help. While Dad and Harold carried the staves on by the armful, R Pratt senior took one at a time. ‘For sure’, he said, ‘the pay will be the same’.[3]

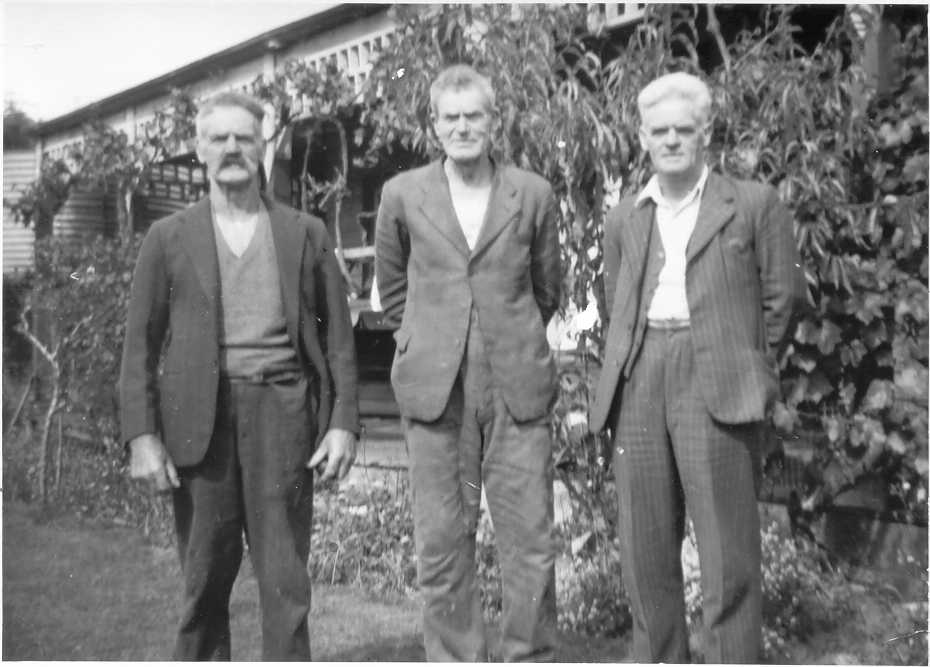

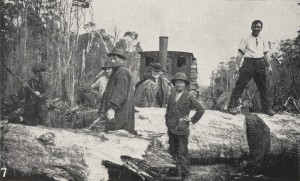

(Left to right) Elijah, Mark and Harold Britton. Twenty-year-old

Harold Britton married nineteen-year-old Laura Fixter

in 1909 and moved to Leongatha, Victoria.

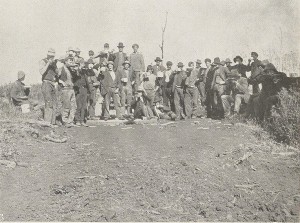

Christmas Hills State School, 1911, with five-year-old Phil Britton (arrowed) front row at left. The teacher pictured is probably Fred Parsons. The original school was a room provided by Tommy and Lizzie Hine, who also lodged the teacher and kept the post office. This was a ‘subsidised’ school, which relied upon the regular attendance of a set number of students and the community providing suitable lodgings for the teacher.

For two years the family lived in a cottage on a small acreage opposite the post office at Christmas Hills, with Elijah only coming home from the mill (four kilometres away) at weekends. While Harold Britton soon dipped out of the business, Mark and Elijah proved an ideal partnership. Elijah, a skilled, mostly self-taught blacksmith, filled the roles of engineer, saw doctor, stoker and timekeeper. He could repair anything mechanical, improvising as needed, and also manned the docker saw. Mark was a fine benchman, an expert at minimising wastage when cutting blackwood. His niece Lorna Haygarth (née Britton) recalled him even bemoaning the fate of heavy timber ends destined for the family fire:

Taking his pipe out of his mouth and putting it carefully on the hearth, he would declare, ‘What a waste, burning this beautiful wood. It should be kept and made into useful articles. Just look at the grain and lovely figure in this piece. It’s real timber, not like some of the pencil wood—it’s heavy, real heavy.’[4]

Mark was a good bullock and horse-driver and had the business brain, keeping the books. Above all, he was a positive thinker. This was essential, because the sight of a five–ton boiler being eased up the Sandhill to the Brittons Swamp site by a twelve–bullock team and a block and tackle signalled the start of a tremendous struggle for survival.

Building the Marrawah Tramway: bridging the Welcome River, 1913. From the Weekly Courier, 13 March 1913, p.20.

Free beer celebration for the construction party at Christmas. From the Weekly Courier, 13 March 1913, p.20

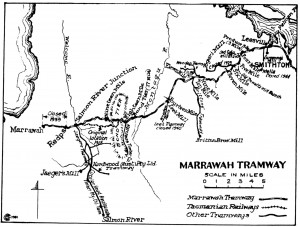

With government reluctant to build roads to bush selections, economic survival in almost impenetrable forest depended on sawmillers making their own path to market. The Marrawah Tramway (1912?–61) was started by JS Lee in order to harvest the timber on the Mowbray Swamp, epitomising the self-sufficiency and initiative of the early Circular Head sawmilling industry. The state government took over the tramway and extended it to Marrawah on the west coast. Then private timber tramways radiated from the Marrawah Tramway into the Montagu, Brittons, Arthur River and Welcome Swamps.[5]

The Marrawah Tramway enters the dolomite Mowbray and Montagu Swamps on its journey from Smithton to Marrawah. Brittons’ branch tramway penetrates Brittons Swamp.

Map by ‘Wanderer’, ‘Railways and Tramways of the Circular

Head District’, Australian Railway Historical Bulletin no.168, October 1951.

Brittons’ line linked their mill to the 9¼-mile mark of the Marrawah Tramway. The 3’6”-gauge Britton Tramway cost about £2,000, a small fortune then. It originally used white myrtle spars for stringers, and was closely corded and ballasted with sawdust so that the five-horse team could haul the trucks of sawn timber (two at a time) without tripping. After a few years, heavy, long hardwood stringers were substituted for the white myrtle ones, and iron rails were placed on the outside bends. Twelve loading ramps enabled twenty-four loads of timber to be left at the junction with the Marrawah Tramway. The timber was then delivered to the Pelican Point jetty at the Duck River heads, where it was loaded on ships bound for Melbourne or Adelaide.[6]

Specialisation in blackwood, supplemented by production of hardwood and other timber, established the Britton’s seasonal regime. The swampy habitat of blackwood made haulage in the drier months essential, with strong, stoic bullocks being favoured for this task. (Horses were preferred to haul hardwood from the drier eucalypt forest.) Logging, cutting and carting in summer gave most of the men a job under cover, milling, in winter, when the weather was bad. In the winter of 1919, for example, Brittons milled about 8,000 super feet (24 cubic metres) of logs per day.

Loss of valuable horses to colic and falling trees prompted the purchase of a 1910 Buffalo and Pitts traction steam engine, which crushed culverts beneath it as it chugged from Forest to its new home. It was fuelled by the abundant wood and water. Elijah Britton devised a cog system which enabled the steam engine to be converted from road to rail, and the tramway was upgraded accordingly. The Buffalo and Pitts hauled sawn timber out to market on the tramway, back-loading with stores. When its boiler eventually rusted out, the engine was replaced by a 1904 Marshall single-cylinder traction engine, which had a better boiler and was a better steamer.

Bush engineering. The Marshall loco, seen here hauling a load of blackwood, was a triumph of improvisation.

Brittons also had this Model T-Ford converted into a dynamic rail motor by Arthur Schmidt of Burnie.

Brittons’ transport problems didn’t end with delivery of timber to the Marrawah Tramway, as the following example illustrates. In 1918 Brittons reached an agreement with Cummings & Co to share the 20,000 super feet of space available on the Holyman steamer ss Hall Cain after JS Lee & Sons had loaded up their guaranteed shipment of 50,000 super feet. Brittons were to ship 15,000 super feet of hardwood to its agents in Melbourne, and delivered this timber to its junction on the Marrawah Tramway. However, timber was already stacked in the way at the junction, including seasoned blackwood owned by Cummings. This forced Brittons to load Cummings’ blackwood onto the vessel before they could load their own hardwood, leading to a dispute between the two companies. Brittons demanded and eventually gained compensation from Cummings.

[1] See Kevin Kiernan, An atlas of Tasmanian karst, Research report no.10, Tasmanian Forest Research Council Inc, Hobart, 1995.

[2] Phil Britton, ‘First Impressions of Brittons Swamp’; ‘The Britton Family’ (notes held by Britton family).

[3] Phil Britton, ‘First Impressions of Brittons Swamp’ (notes held by Britton family).

[4] Lorna Haygarth (nee Britton), ‘The Britton Story’ (notes held by the Britton family).

[5] ‘Wanderer’, ‘Railways and Tramways of the Circular Head District’, Australian Railway Historical Bulletin, no.168, October 1951, pp.151–52.

[6] Phil Britton, ‘The Britton Family’, pp.5–7 (notes held by Britton family).

Loving reading all about history etc. Thankyou Nic. I will download it all and print and laminate and share with our children and grandchildren.

Thanks, Ann, this material will be part of a book some time in the future. The hardest part of writing this family history will be getting around the living, rather than dealing with past events and people who are gone. I hope by posting some of the past on this site that I can engage with members of the greater Britton family and get their input.

Great start Nic. I’m loving reading the story Mum told me over the years & with the added pieces of research you have included the story is coming to life.

Thanks, Jean, of course I have written a lot more than this but I didn’t want to post anything that wasn’t in a coherent draft form. I will post some more pieces from this story in the coming days.