Old Hooky was no new chum—

All his life he’d chased the gold.

And judging by his ‘skiting’

Won—and squandered—wealth untold.

He’d chased it in the Yukon,

In Alaska’s ice and snow,

And north from hot Coolgardie

Where the toughest only go.[1]

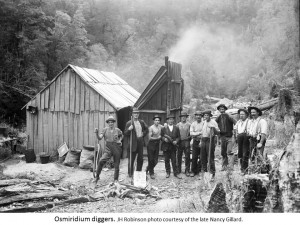

The toughest also tackled Tasmania, chasing osmiridium, and that’s where ossie digger Henry Humphries penned these words about his old mate ‘Hooky Jack’. The one-armed prospector, born as John D’Ahren Baptiste, spent at least three decades on Australian shores chasing everything that glittered. And he had a way of finding it:

A lucky man was Hooky and,

In truth, no matter where

He sank the most unlikely hole

There’d be some ‘metal’ there.[2]

Luck or skill? I fancy the latter. You don’t storm goldfields without learning the how, where and why of finding precious metals.

But who was Hooky Jack, and where did he come from? He is said to have inherited the equivalent of £30,000 ($60,000) in his home town of Madeira, Portugal, back in the 1880s, before embarking on his tour of world goldfields.[3] Perhaps squandering his inheritance was the start of a dissolute life, a rollicking refrain of tramp steamers, bars, brothels and all the trappings of the wild west.

It seems unlikely that Baptise made a fortune on Australian gold or Tasmanian osmiridium, although, admittedly, he is a hard man to track on local soil. Prospectors of a century ago often managed to elude electoral rolls, censuses and other public records. Although ships’ logs, gazetted mining leases and court cases are the historian’s allies, the John Baptistes of Australia take some sorting. Newspapers of his day bore so many references to the biblical John the Baptist, to St John the Baptist churches, guilds, fetes, lodges and French statesmen that following the prospector’s life is a painstaking affair. He wasn’t John Baptiste the Portuguese sailor executed for murder at Perth in 1900.[4] Nor was he the Sydney nurseryman John Baptist, and as for the Parisian sausage maker and confectioner from Wagga Wagga … let’s just say that these would be surprising career moves for a carousing wastrel.[5]

Happily, John D’Ahren Baptiste had some distinguishing characteristics which aid identification. One was his love of rum, another the colour of his skin. Baptiste was referred to as a ‘coloured gentleman’ and a ‘half caste’. There was hilarity in a North Melbourne courtroom when in 1895 he was summoned to answer a paternity suit. Baptiste’s defence submitted that the complainant, Annie Boddington, had no proof that he was the father of her newborn. Boddington’s response was to produce the dark-skinned infant, shouting, ‘Haven’t I! He’s a black man—and there’s no mistake about this lot’. The judge seems to have accepted this rather flimsy ‘evidence’, ordering Baptiste to pay maintenance.[6]

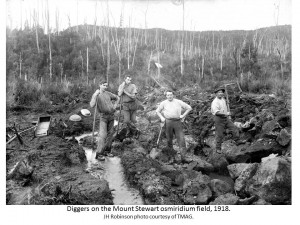

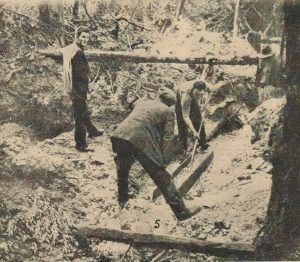

Baptiste’s most distinctive trait was his hook. Various prosthetics led the way on the osmiridium fields. ‘Peg Leg Ted’ Loughnan climbed Mount Stewart on one good leg to peg a reward claim in 1917.[7] Lost Adamsfield schoolteacher Tom Cole was tracked along the Gell River by indentations left in the soil by his wooden leg in 1938.[8] It helped carry him into eternity. Baptiste’s metal hook beat those wooden legs for versatility. It raked the fire, served as a fork in food preparation and hoisted the billy from the hot coals. He could saw with it, swing a pick and chop with it.[9] In a brawl he was even said to have used his hook as a club.[10]

Exactly how or when he lost his hand is unknown. Certainly he had the hook during his time on the Gippsland goldfields, Victoria, during the early 1900s.[11] Max Dyer described Baptiste as

‘probably the best miner to ever sluice gold along the Mitta Mitta. Folks used to say that Hookey [sic] could smell gold, as he was never known to have a useless claim. He had a drinking problem as well, and my mother had often told me of Hookey waving his hook in the air and cursing all and sundry … when he was in town on a bender. This only happened occasionally and when he was working his claim he gave it his undivided attention’.[12]

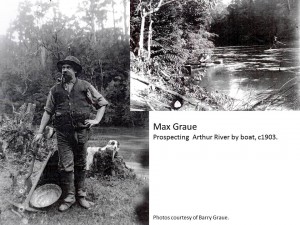

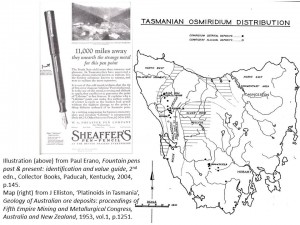

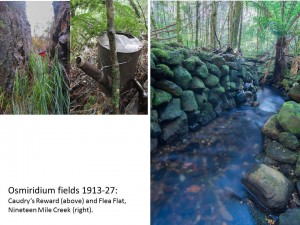

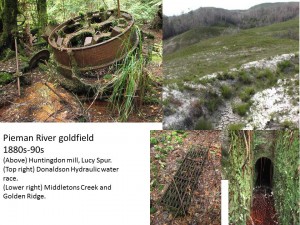

Yes, Hooky Jack knew his business and had plenty of nous. This was apparent when he arrived on the Nineteen Mile Creek osmiridium field nineteen miles west of Waratah. In 1914 stockpiling caused a dramatic slide in the osmiridium price, so he stashed nineteen ounces at the Waratah Post Office and returned to Gippsland, where he registered the Hard to Seek gold claim.[13] Negotiations over sale of that osmiridium stash continued while he was in New Zealand 1916–17, and he probably disposed of it in 1918 when the price almost doubled.[14]

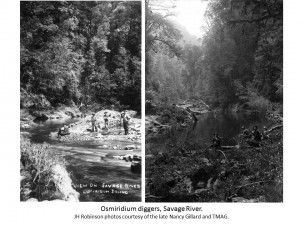

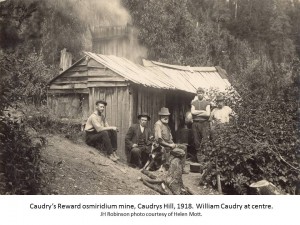

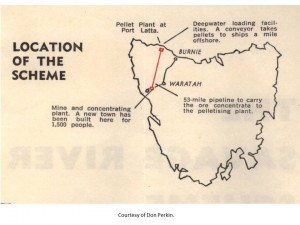

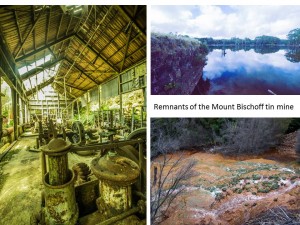

With Russia engulfed in civil war, Tasmania suddenly had a world monopoly on the point metal osmiridium used to tip the nibs of gold fountain pens. Baptiste hit the new Mount Stewart ossie field in the foothills of the Meredith Range. Later he tried Savage River, working firstly with Harry Stanley, then with Charles Connors. His partnership with the latter ended in 1923 after the Portuguese spent nineteen days in the Waratah Hospital recovering from several blows to the head with a vase.[15]

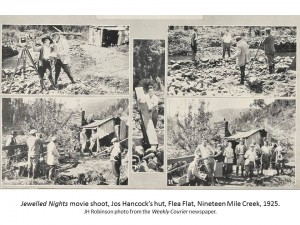

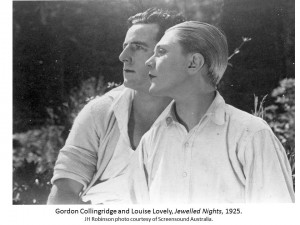

Baptiste fared better with former policeman Percy Marsh. The pair was among the first diggers to follow the Stacey parties to the Adams River osmiridium field in June 1925. There the Adamsfield poet ‘Mulga Mick’ O’Reilly claimed to have found Baptiste doing so well that he employed two men: one carried his stores in from the Florentine River, while another ‘did his cooking, fetched his whisky from the sly-grog shop, and put him to bed at night’. One report was that he sold his claim for a bottle of rum.[16] Another had Baptiste making £8000 in three months with Marsh at Keep it Dark Gully—a sly reference to his skin colour?—before selling the claim for £350.[17] Again, however, rum may have been his downfall, as he claimed to have been robbed of £200 of his winnings in Hobart in December 1925.[18] Perhaps this is what caused him to default on payments for a block of land at Prince of Wales Bay, Glenorchy, in 1927, losing his investment.[19] By then Hooky Jack was back on the west coast, prospecting for tin in the Norfolk Range.[20]

Baptiste was done with the ossie, but what happened to his winnings? Was it a case of easy come, easy go in a string of Hobart pubs and brothels? And what happened to him? He was not the supposed 64-year-old Frenchman John Baptiste who died at Broken Hill in 1938.[21] Nor did he go missing on the Great Depression gold trail like Harry Bell Lasseter. Baptiste appears to have seen out his days prospecting for gold in Gippsland, a naturalised Australian who passed the age of 80.[22] Perhaps, like Sammy Dwyer, last man at the Nineteen Mile, he was content to scrape a subsistence living from an old field he knew well, cooking in a camp oven, growing a few vegetables and reading about a world that had passed him by.

[1] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate (Burnie), 31 March 1962, p.13.

[2] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate (Burnie), 31 March 1962, p.13.

[3] ‘Along the “ossy” track’, News (Hobart), 10 September 1925, p.1.

[4] ‘The Ethel mutiny and murders’, West Australian (Perth), 18 June 1900, p.2.

[5] See, for example, ‘Progress of the suburbs’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 February 1914, p.8; and advert, Wagga Wagga Express, 15 August 1895, p.4.

[6] ‘A black bit of evidence’, Age (Melbourne), 18 October 1895, p.6.

[7] For Loughnan’s application for a monetary reward for his and Stanton’s discovery, see Edward Loughnan to Sir Elliott Lewis 23 December 1920, AB948/1/98 107B ‘Correspondence: osmiridium’ (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart).

[8] ‘Feared that missing prospectors have been drowned’, Advocate, 17 June 1938, p.6.

[9] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate, 31 March 1962, p.13.

[10] ‘Waratah assault case’, Advocate, 19 November 1923, p.5.

[11] The Commonwealth of Australia electoral rolls for 1903, 1908 and 1909, State of Victoria, Division of Gippsland, roll of electors for the Subdivision of Omeo, described John Baptiste as a miner at Mitta Mitta. In 1911 his 30-acre gold lease on the Bemm River, Gippsland, was gazetted as abandoned (‘Gazette notifications’, Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (Victoria), 2 September 1911, p.2). He was naturalised on 29 November 1911 at the age of 49, Victoria, Index to naturalisation certificates, no.12861, https://www.ancestry.com.au/interactive/60711/44441_346529-02210?pid=16656&backurl=http://search.ancestry.com.au/cgi-bin/sse.dll?_phsrc%3DAEX134%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource%26usePUBJs%3Dtrue%26gss%3Dangs-g%26new%3D1%26rank%3D1%26gsfn%3Djohn%26gsfn_x%3DNIC%26gsln%3Dbaptista%26gsln_x%3DNN%26msbdy%3D1865%26msbpn__ftp%3DPortugal%26msbpn%3D5184%26msypn__ftp%3DMelbourne,%2520Victoria,%2520Australia%26msypn%3D97862%26cpxt%3D1%26cp%3D2%26MSAV%3D1%26MSV%3D0%26uidh%3D2l5%26pcat%3DROOT_CATEGORY%26h%3D16656%26recoff%3D6%25208%26dbid%3D60711%26indiv%3D1%26ml_rpos%3D1&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=AEX134&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true, accessed 17 June 2017.

[12] Max Dyer, Hot air, bee stings & echoes: more bush yarns, the author, Bairnsdale (Victoria), 2006, pp.5 and 49.

[13] HB Silberberg to Bert Osborne, 8 May 1914, File 64-2-14, HB Selby & Co Papers (Noel Butlin Business Archive, Canberra); advert, Snowy River Mail (Orbost, Victoria), 11 December 1914, p.2.

[14] HB Selby to John Baptiste, 14 December 1916 and 19 January 1917, File 64-2-17, HB Selby & Co Papers (Noel Butlin Business Archive, Canberra);

[15] ‘Waratah assault case’, Advocate, 19 November 1923, p.5.

[16] MJ O’Reilly (‘Mulga Mick’), Bowyangs and boomerangs: reminiscences of 40 years’ prospecting in Australia and Tasmania, Hesperian, Carlisle (Western Australia), 1984 reprint, p.160.

[17] ‘The sifting out’, Examiner, 25 December 1925, p.5; ‘Adams River osmiridium field’, News (Hobart), 9 September 1925, p.1.

[18] ‘The morning after’, Daily News (Perth), 30 December 1925, p.1.

[19] Advert, Mercury, 16 November 1927, p.12.

[20] ‘Reported missing: prospector returns to camp, Mercury, 29 July 1927, p.6.

[21] ‘Wilcannia-Forbes Diocese’, Catholic Press, 22 September 1937, p.27.

[22] The Commonwealth of Australia electoral rolls for 1931, 1934 and 1943, State of Victoria, Division of Gippsland, roll of electors for the Subdivision of Leongatha, described John A Baptista as a prospector at Walkerville, via Fish Creek.