Hikers love drama. Launceston photographer Steve Spurling (Stephen Spurling III, 1876‒1962) manufactured some in 1908 when he set out on a hike with his mates Knyvet Roberts (1872‒1959) and John Burns (Jack) Scott (1873‒1915). Their journey to Lake St Clair was ‘a terror incognito!’, since they could get ‘no reliable information as to what lay before us, and were not encouraged by rumours of precipitous valleys and impassable bogs …’[1]

In other words, Spurling didn’t know who to ask for information on his proposed route. In 1908 there were no walking clubs which later acted as a repository of local hiking knowledge. Spurling had few useful maps and no access to the shepherds and hunters who had been working the lake country for decades. Had he only known, in five minutes he could have hotfooted it from his office at Spurling Studios down to the legal firm of Law & Weston & Archer, two of the principals of which had, as schoolboys, crossed the lake country to Lake St Clair 22 years earlier.[2] Or called on Delorainite Dan Griffin, the temperamental highland journalist who had scouted the Lake Ina area for a west coast stock route, finding only a thylacine in the business of taking a leg of mutton home to her family.[3] These men could have told him where to go and what to expect.

Spurling was then at the height of his physical powers, being instructor to the Union Jack Gymnasium Club.[4] Knyvet Roberts, a fellow traveller on Spurling’s 1905 Cradle Mountain climb, and Jack Scott, with whom Spurling had sporting connections (Union Jack Gymnasium Club, lacrosse and rifle shooting), are also likely to have been in fine fettle. They sure looked that way when Spurling photographed them gazing steely-eyed across a paddock somewhere between Deloraine and Western Creek. While his mates toted simple haversacks, Spurling, in addition to his swag and photographic case, slung a bag around his neck. How did his glass plates ever survive long enough to be processed, let alone exposed? More importantly, when did the cravat cease to be a bushwalking accessory and are we the poorer for it?

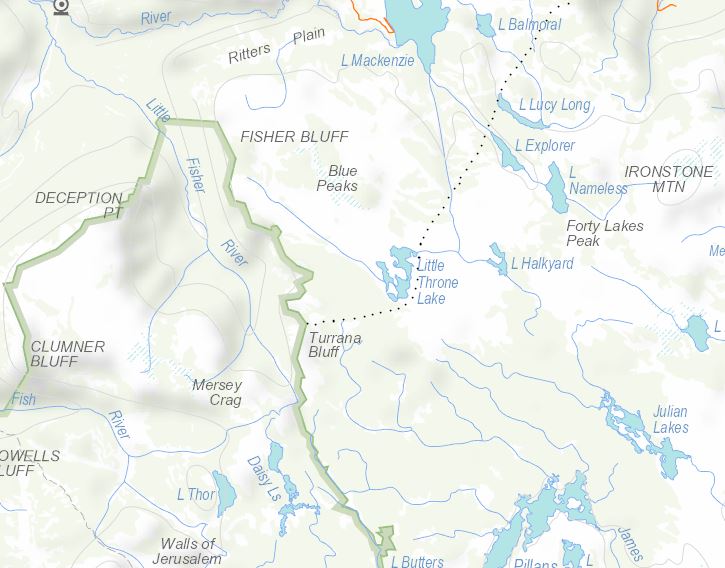

Spurling’s purpose was to supplement the landscape catalogue of Spurling Studios. The Daily Telegraph’s Deloraine correspondent must have been suffering his own ‘terror incognito’, judging by his description of the party’s plans to cross ‘via Mount Ironstone and Lake St Clair for Cradle Mountain’.[5] The trek started inauspiciously. Alighting from the Higgs Track into a Lake Balmoral blizzard, the men set the compass for Mount Olympus, about 50 kilometres away as the crow flew. Twenty-seven-kilo packs barely provisioned them for the five days of tramping ahead, with innumerable detours around tarns, battles with bauera and dense Richea scoparia (‘gas bush’), and even a near thing with quicksand. At nightfall on Day Two they camped near ‘the lakes of the Hay Moon Marshes’ (presumably Chummy Lake and Lake Denton, near Halfmoon Marsh, Pine River) on the Great Pine Tier.

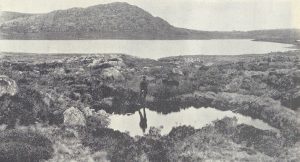

From here the trio must have swung around to the west. On Day Four they approached a large, uncharted, unnamed lake ‘almost due south of Rugged Mt [a named then used to describe the group of peaks from the Walls to Mount Rogoona and those overlooking Lees Paddocks], ’ measuring about three miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide—possibly Lake Norman or Lake Payanna in the Mountains of Jupiter. This was probably the feature Spurling dubbed the Courier Lake. Was he buttering up the Weekly Courier newspaper that bought so many of his photos? Spurling’s companions also named another lake (now Lake Riengeena) after him at the time. The serrated head of the Acropolis now loomed high in the summer haze far across the Narcissus Valley. Rounding the shoulder of ‘an unnamed mountain’ (now Mount Spurling), they scrambled down the Traveller Range to camp at Lake Laura, just to the north-east of Lake St Clair.

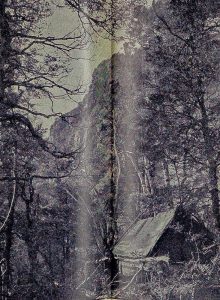

On Day Seven Spurling’s party resettled at the mouth of the Narcissus River, a site which would find favour with future Lake St Clair campers. After a week’s exertion, the photographer was too knackered to attend the usual dawn service of his profession. He had not stirred from his bed next morning when one of his mates roused him, ‘Steve, get up, there’s a cloud over Mount Olympus!’ By the time the lens was brought to bear, the rising mist cloaked only the mountain’s lower baffles, resulting in one of Spurling’s most striking compositions.

Food supplies were now desperately low. After conquering Mount Olympus, base camp was moved to the Byron Gap in hope of landing some game. ‘Hedgehog’ (echidna) stew had fed the party for a while, but their snares continued to draw a blank. Lake Marion, Mount Gould and the Cuvier Valley completed the sightseeing, before the visitors made a dash for the accommodation house at the southern end of the lake, hoping to beg provisions from other tourists. The place was empty—but for a small packet of flour. Spurling, Scott and Roberts quickly turned this into a barely edible rock-hard damper. Appetites whetted, they determined to partake of the superior cuisine available at the Pearce residence, 20 kilometres away. There the ‘three wild eyed haggard bearded sun-downers’ must have presented quite a sight hoeing into their ‘Lord Mayors Banquet’.

Homeward bound, they took the stock track from Bronte to Great Lake, reaching the shepherd’s hut at the Skittleball Plains near Great Lake on the twelfth night of their journey. The 4139-acre sheep run between the Ouse and Little Pine Rivers was stocked by Edmund Johnson of Lonsdale, near Kempton. The identity of his shepherd is unknown, but he kindly offered the party his floor. Revived by their hearth-side sleep, Spurling, Scott and Roberts pulled out all stops for the final dash along the lake and down Warners Track, taking their tally for the last three days of the tramp to 130 kilometres. The reason for their haste was that at the Pearce homestead arrangements had been made to have a driver await the party with a dray at Jackeys Marsh. ‘The luxury of driving was unspeakable’, Spurling wrote in an excursion diary which, like the 1840s survey maps that might have aided him, was never published.

Spurling’s photos from the trip featured in the Weekly Courier newspaper over many months.[6] They also appeared as postcards (they are collectables today) and in ‘bioscope’ lantern slide performances which Spurling conducted in Launceston, that is, as slides incorporated into a moving picture show.[7] In 1913 he would return to Lake St Clair with a movie camera, as Simon Cubit and I detailed in Historic Tasmanian mountain huts.[8]

Major Jack Scott was killed in action at Gallipoli on 8 October 1915, having joined up in Western Australia alongside his brother Joe Scott—who likewise lost his life during the Dardanelles Campaign.[9] Knyvet Roberts, after whom Knyvet Falls, Pencil Pine Creek, are named, became a Flowerdale farmer. His son, the writer Bernard (Barney) Roberts, treasured an album of 30 photos which Spurling had given his father after the 1908 Lake St Clair trip. Barney used these photos to introduce me to the photography of Steve Spurling, for which, 30 years later, I am extremely grateful.

[1] Spurling’s unpublished account of the trip, ‘Across the Plateau’, is held by the Spurling family in Devonport. It appears to be a typed version of hand-written Spurling notes and is wrongly dated February 1913, giving the impression that the author and the typist were not one and the same.

[2] For the accounts of this trip see ‘The Tramp’ (William Dubrelle Weston), ‘About Lake St Clair’, The Paidophone, (Launceston Church of England Grammar School magazine), vol.II, no.7, September 1887, pp.7‒8; and ‘Shanks’s Ponies’ (William Dubrelle Weston), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Examiner, 22 December 1888, p.2 and 29 December 1888, p.13. For Weston and Law’s hiking careers, see Nic Haygarth, ‘”The summit of our ambition”: Cradle Mountain and the highland bushwalks of William Dubrelle Weston’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.56, no.3, December 2009, pp.207‒24.

[3] ‘Lake Ina’, Daily Telegraph, 24 May 1907, p.4.

[4] ‘Union Jack Gymnasium Club Annual Meeting’, Daily Telegraph, 17 March 1908, p.8.

[5] ‘Deloraine’. Daily Telegraph, 18 February 1908, p.7.

[6] Photos from the 1908 trip appeared in the Weekly Courier on 16 April 1908, p.27; 23 April 1908, p.19; 30 April 1908, p.17; 7 May 1908, p.17; 14 May 1908, p.17; 21 May 1908, pp.21 and 22; 28 May 1908, p.17; 11 June 1908, p.24; 2 July 1908, p.17; 9 July 1908, pp.17 and 23; 16 July 1908, p.22; 23 July 1908, p.23; 6 August 1908, pp.20 and 24; 31 December 1908, pp.21 and 24.

[7] See, for example, ‘Bioscope entertainment’, Daily Telegraph, 29 September 1908, p.3.

[8] ‘Hartnett’s huts’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.76‒83.

[9] ‘Major JB Scott killed: brothers make the supreme sacrifice’, Examiner, 16 October 1915, p.6.