by Nic Haygarth | 25/05/20 | Tasmanian high country history

The man with the possum-skin bag on his back studied the rocks as he sloshed his way down the river with Bravo, his collie-spaniel cross. James ‘Philosopher’ Smith sought the motherlode of the Arthur River gold. Ahead of him, the low summer stream rippled as it received a tributary from the east. Smith’s partly speculative Henry Hellyer map suggested that this was the Waratah River. In its dark mouth he searched for wash—sand and detritus carried down by the current—and promising rock formations. At a sandbar he swirled something black in his dish which in the half-light resembled tin. He had seen tin oxide almost two decades earlier at the Victorian gold rushes, but the tiny quantity in his dish now caused him no excitement. He returned to the Arthur to resume his search for gold.

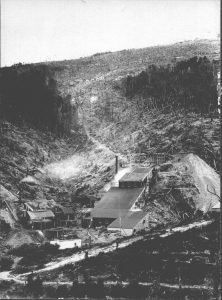

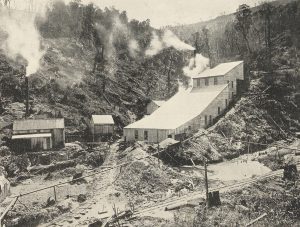

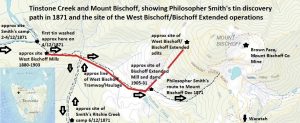

Base map courtesy of LISTmap (DPIPWE).

It was only two days later, when the sun’s rays poked through the myrtle forest, that the opportunity arose to examine the sample under the lens. What struck Smith about it was that many particles were angular. The sample was little waterworn, which meant he had found it close to the matrix.

Smith rushed back to the ‘Waratah’, which was actually today’s Tinstone Creek. For a further two days he panned and picked at the course of the stream, but it wasn’t until he ventured above its Ritchie Creek confluence that his pick opened the bed of porphyry he sought. The adrenalin must have pumped as he climbed the stream. Within a few minutes he obtained a quarter of a kilogram of tin ore. He picked crystals out of crevices in the creek bed, and at the source of one of its tributaries, where Mount Bischoff Co tailings were later piled, Smith washed more than a kilogram of tin to the dish. He had found the motherlode.[1]

The site, at the junction of the Arthur River and Tinstone Creek, where Philosopher Smith washed the first Mount Bischoff tin. Today the startlingly yellow waters of Tinstone Creek tell the tale of Bischoff’s mining legacy. Nic Haygarth photos.

A ‘mountain of tin’, Mount Bischoff, stood above him. Over 74 years the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company would produce 56,000 tonnes of tin metal and pay dividends of more than £2.5 million on paid-up capital of only £29,600, one of the great success stories of Australian mining.

As usual, the company with the first choice of ground and best access to capital dominated the mining field. That wasn’t the West Bischoff Tin Mining Company which, ironically, worked in the valley where Smith made his discovery. Take a walk in Philosopher’s footsteps and you can see the scars of its struggle.

Sacrificial human showing the scale of a West Bischoff Tramway cutting, Tinstone Creek. Nic Haygarth photo.

Ritchie Creek bustling through spindly regrowth. Here Philosopher got side-tracked for a day. Nic Haygarth photo.

Bogey wheels from the horse-drawn tramway. Nic Haygarth photo.

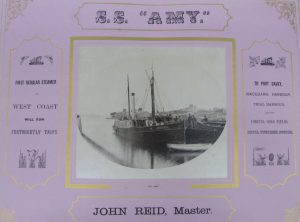

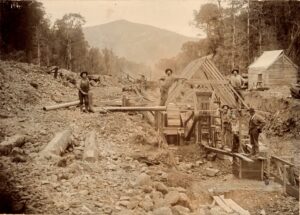

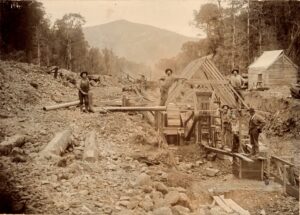

The West Bischoff’s early mill site is not far from Philosopher’s discovery point near the junction of Tinstone Creek and the Arthur. That’s about as close as the company got to success. Here Cornish tin dressers WH Welsey and William White worked with a 15-head stamper battery driven by a 28-foot-diameter waterwheel. The plant was served by races from Ritchie Creek and the Arthur River, an inadequate water supply which probably reduced the company’s viability.[2] Beginning with a paid-up capital of £20,000, between 1878 and 1892 the West Bischoff Co made 26 calls on shares—and paid no dividends whatsoever.[3]

West Bischoff mill and water wheel. Stephen Hooker photo, NS1192-1-1 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

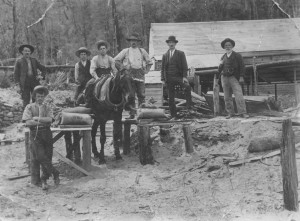

Friends of the water wheel, from the Colin Dennison Collection, University of Tasmania Archive, photo cleaned by Jeff Crowe.

Machinery drive shaft still in place. Nic Haygarth photo.

Some remaining timber fluming on a water

race. Nic Haygarth photo.

Collapsed boiler chimney in the old water wheel pit at the West Bischoff Mill. Nic Haygarth photo.

A 2.5km-long wooden, horse-drawn tramway and haulage connecting the plant to the mine in the western flank of Mount Bischoff included a 30-metre-long bridge over Ritchie Creek. [4] Thanks to Winston Nickols’ dogged research, track cutting and marking, much of the old tramline can now be retraced along the edge of the highly degraded Tinstone Creek. The impressive tramway cuttings and the horrible, spindly regrowth resulting from clearing the old forest give some idea of the original company’s enterprise. The yellow glop in the creek is fed by acid mine drainage (that is, low level sulphuric acid) escaping from the West Bischoff/Bischoff Extended adits.

By March 1892 the West Bischoff Co had driven its no.3 tunnel more than 400 metres, but the cost of all the infrastructure left it unable to afford a calciner which could have purified its ore by roasting out the arsenic.[5] The company was wound up, being replaced by another inadequately funded company, the New West Bischoff. The infrastructure on the property was by now so run down that it was cheaper to crush at the adjoining Stanhope Tin Mining Company battery than use its own, so the company employed Stanhope Co manager Richard Bailey to run the two mines concurrently.[6] While the New West Bischoff facilitated this change by building another tramway, in January 1893 its own plant was destroyed by bushfire.[7]

Stamper rods and part of the camshaft of the battery, West Bischoff/New West Bischoff Mill.

(Right) Charred remains of the blacksmith’s shop. Nic Haygarth photos.

The signs of this fire remain today at the multi-levelled site of the old mill, where the stamper rods, blacksmith’s shop, boiler stack and water wheel pit are still evident. The New West Bischoff lurched towards defeat. No Australian buyer wanted its unroasted arsenical tin ore, forcing it to ship it to England for treatment and sale.[8] The bank foreclosed on the company, finally selling the property to Wynyard investor Robert Quiggin in 1895.[9] After seventeen years of work at this site, the first dividend remained elusive.

The route from Waratah down Tinstone Creek to the Arthur River and over the Magnet Range was cut as a track in 1879, and when the mining settlement of Magnet was established in the 1890s it became an 8km pedestrian conduit between Waratah and its satellite mining town. Come night or day people padded between the centres, attending dances, courting darlings, cutting firewood and even moving stock. Today you rarely glimpse the ‘glorious’ walk of yesteryear, that ‘never-ending avenue of most beautiful greenery which arches overhead so closely at times as to form a veritable living tunnel’.[10]

No record survives of anyone hitching a ride up the hill on the West Bischoff tram, but those passing the old burnt-out mill site in 1901 would have dodged horse teams, haulage contractors and carpenters. A third company, the Mount Bischoff West Tin Mining Company, registered in Victoria, was building a new mill. It had paid-up capital of only £16,000, but a higher tin price in its favour.[11] Another crushing device, a Krupp ball mill, replaced the original battery and two concentrating tables were installed to separate the ore. The machinery was driven by a water-driven 98-horsepower turbine.[12] Drop in to see the concentrating tables and the amalgamating pan that possibly replaced the ball mill. The latter must have proven too hard to salvage when in 1903 the plant was abandoned and the property left in limbo again.

Pesky photo-bombing photographer with the amalgamating pan.

Phoenix Weir concentrating tables. Thanks to Winston Nickols for his technical research.

Nic Haygarth photos.

So far we have tarried in the bottom end of the Tinstone Creek valley. Now we cross Ritchie Creek, up which Philosopher camped after getting side-tracked trying to trace the tin. Above this confluence he rediscovered the black waterworn particles of the cassiterite or tin oxide that later made the Mount Bischoff Co famous. By the late 1890s this company had bought out most of its early rivals, but it saw no advantage in buying the West Bischoff property. Instead, in 1905 company number four, the West Bischoff Extended Tin Mining Company (later simply the Bischoff Extended), took over the leases and erected a new mill much higher up Tinstone Creek below its mine. When the scrub was lower than present you could still see the brick chimney and roaster shafts of its 1910 calciner, the first on the Bischoff field.[13]

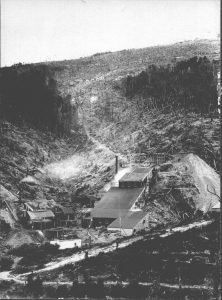

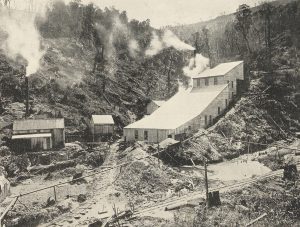

The first, steam-driven Bischoff Extended plant on Tinstone Creek, showing the tramway connecting it to the workings above it on the western side of Mount Bischoff. Photo courtesy of the Waratah Museum.

Bischoff Extended Mill, 1911. Photo probably by JH Robinson from the Weekly Courier, 25 May 1911, p.24.

From here on Mount Bischoff was a two-horse tin field. The better capitalised Mount Bischoff Co threw its weight around, alleging that the Bischoff Extended had encroached onto its lease. The expensive High Court law suit which resulted hampered the struggling company’s progress.[14] So did reduced production when World War One closed the European metal market.[15] The first dividend, 39 years in the making, was declared in 1917, but although several more followed up until 1920, the company soon returned to making calls on shares. Further technical advances, including electrification of the plant in 1925, were made in the face of rising costs and falling metal prices.[16] Mostly sporadic operation continued until the mine was abandoned in 1931.[17] A six-bullock team hauled a large boiler up the hill to Waratah, but much of the plant remains on site rusting ever deeper in the regrowth.[18] Welcome to the Tarkine industrial wilderness.

Life at the Bischoff Extended in 2004. Tiger snake sunning himself on burnt remains of the feed floor at the top of the mill.

Calciner chimney.

Three lichen-encrusted roasting shafts crowned with gear wheels, Bischoff Extended Calciner. Nic Haygarth photos.

Your walk in Philosopher’s footsteps has now reached the base of the hill below Mount Bischoff. It’s a hard slog to the top, but imagine how much worse it was for the man on a daily ration of 100g of bread and a pint of tea.[19] That dish full of ‘black gold’ he won at the head of Tinstone Creek was the only tonic Smith needed. He had no food but he had a fortune. For the Mount Bischoff Co’s smaller rivals, destined to collect ‘the crumbs from the rich man’s table’, there was no pay-lode and no payday, just bread-and-butter toil for the working man and a poisonous legacy for the upper Arthur River.

[1] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, afterwards TAHO).

[2] HK Wellington; in DI Groves, EL Martin, H Murchie and HK Wellington, A century of tin mining at Mount Bischoff, 1871–1971, Geological Survey Bulletin, no.54, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1972, pp.61 and 64.

[3] Journal of the West Bischoff Tin Mining Company, NS1012/1/51 (TAHO).

[4] James FitzHenry, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Tasmanian Mail, 9 July 1881, p.21.

[5] Pretyman to FA Blackman, 23 March 1892, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[6] Pretyman to Robert Mill, 25 August 1892, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[7] For the tramway, see Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 7 December 1892, 14 December 1892 and 18 January 1893. For the fire, see Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 17 January 1893, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[8] Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 29 September 1892; Pretyman to Claperton, 24 January 1894; NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[9] Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 9 August 1895, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[10] ‘WGT’, ‘Further rambles with the Scouts’, Advocate, 26 January 1924, p.12.

[11] ‘Mount Bischoff West’, Examiner, 14 March 1901, p.2.

[12] ‘West Bischoff tin mine’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 26 September 1901, p.3.

[13] ‘Mount Bischoff Extended’, Advocate, 6 September 1907, p.2.

[14] ‘Bischoff Extended’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 May 1913, p.1.

[15] ‘Mount Bischoff Extended’, Daily Post, 18 May 1915, p.8.

[16] HK Wellington, A century of tin mining, p.58.

[17] HK Wellington, A century of tin mining, p.61.

[18] ‘Waratah: 8-ton boiler raised from Bischoff Extended’, Advocate, 24 March 1933, p.8.

[19] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 31/01/17 | Tasmanian high country history

Five-head battery at the Carn Brea tin mine, the only battery remaining in situ on the Heemskirk field. Nic Haygarth photo.

A lode tin mining boom in western Tasmania followed Inspector of Mines Gustav Thureau’s poorly considered 1881 claim that ‘the Mount Heemskirk and Mount Agnew tin deposits appear to be … of grave importance to the Colony at large’ and that ‘their permanence has already been proved …’[1] As Thureau discovered, when he arrived there unwisely in winter, the difficulties of working the remote field were enormous. It was an exposed coastal area characterised by cold winters, driving rain, dense vegetation and steep terrain. There were no roads, and no useful supply routes. The closest thing to a port was Trial Harbour, a shallow inlet open to the winds which crashed the Southern Ocean onto the coast.

Tasmanians subscribed to the idea that Cornish miners were the model of practical, economical tin mining. Trained-on-the-job Cornish miners were in great demand at Heemskirk, and they encouraged their excited employers with ludicrous allusions to their homeland. In August 1881, for example, one of the Heemskirk mine managers, Robert Hope Carlisle, was said to be trying to trace the continuation of the famous Dolcoath tin lode from Cornwall across the oceans to Heemskirk.[2] However, their assertions that Tasmanian tin lodes would ‘live down’ like Cornish ones proved disastrous on a field where the deposits were actually small and inconsistent. Ironically, the fortunes of one novice Cornish miner, Josiah Thomas (JT) Rabling, in Tasmania suggest that Heemskirk was indeed the ‘Cornwall of the antipodes’, that is, it proved as hard to make a living on the Tasmanian tin fields as it was in the depressed Cornwall he had escaped.

Josiah Thomas Rabling

Rabling was the Cornishman chosen to work the Carn Brea Tin Mine at Heemskirk. He was born into a well-known Camborne, Cornwall mining family in about 1843, the fourth of eight children.[3] As the nephew of William Rabling senior, who had made his name and fortune in the Mexican silver mines, and also the nephew of Charles Thomas, manager of the famous Dolcoath Mine at Camborne, he was born with a mining pedigree.[4] Josiah’s father, Henry Rabling, mined in Mexico, but does not appear to have succeeded there, leaving effects to the value of less than £450 when he died in 1875.[5] The fact that Josiah Rabling was in the workforce at the age of seventeen suggests that his mining education was on the job, rather than in the class room—and there was no Camborne School of Mines until 1888. Rabling grew up at a time when England lagged behind countries like Germany and the United States of America in not having a mining academy system.[6] In 1861 young Rabling was a smith, in 1871 he was a mining clerk at Camborne, near the Great Flat Lode of tin mines and the Dolcoath Mine, which produced copper and tin for centuries.[7]

However, the crash of the copper price in the second half of the nineteenth century, the effect of the cost book system and Cornwall’s lack of a coal resource on its industrial economy, and additional failures in agriculture and fishing placed great stress on Cornish mine workers and labouring families. By 1873 the tin price was also falling, and 132 Cornish tin mines closed over the next three years.[8]

It is likely that the death of Rabling’s father in 1875 and the downturn in the local mining industry necessitated a search for work elsewhere. Competition to Cornwall from the Australian tin mines had begun with almost simultaneous discoveries on the New England tableland in northern New South Wales and at Mount Bischoff in Tasmania. Rabling arrived in Tasmania on the Argyle in 1876, perhaps being sent by British capitalists interested in Tasmanian mines.[9] During 1877 and 1878 he secured commissions to report on various mines, but by the following year was down on his luck. In August 1879, after making a little money by paling splitting, he forged a signature on a cheque which he presented in the town of Waratah (Mount Bischoff) to pay a small cartage fee incurred by a friend. He pleaded guilty to a crime committed in ‘such a childish manner’, according to a reporter for the Mercury (Hobart) newspaper, ‘with so little gain attached to it that it really looked as if he wanted to get into prison’.[10] Despite this being a first offence, Rabling was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment.[11] The effects of this experience are unknown, but one subsequent effort to make a living in Tasmania also landed him in trouble. In July 1881, along with three other men, he was tried in the Supreme Court, Hobart, on a charge of unlawfully conspiring to defraud Peter McIntyre to the tune of £400 by salting the Band of Hope Mine. Rabling and one other were found not guilty.[12]

Despite these events, such was the allure of the Cornish ‘practical miner’ that only a month later Rabling was one of two men engaged by the British Lion Prospecting Association to prospect on the Heemskirk tin field.[13] The Heemskirk tin deposits, like those of Mount Bischoff, occurred in granite—and who knew more about working tin in granite than Cornishmen?

A tributary of Granite Creek was the site of one of three Heemskirk sections leased by Rabling. The creek, he said, would be sufficient to drive machinery.[14] Even today the site, within a several hundred metres of the sea, is a remote one, three hours’ walk from shack settlements at Trial Harbour and Granville Harbour. It is hard to imagine what a young man from Camborne made of tent life exposed to the roaring surf of the Southern Ocean.

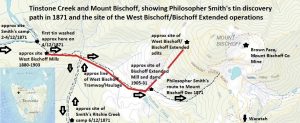

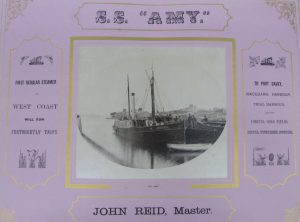

The ss Amy at dock.

Anson Brothers photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Even being delivered to the Heemskirk field was an endurance test. Rabling first ventured westward out of Launceston on the small steamer the ss Amy, which had begun to unload if not dock at Boat (later Trial) Harbour.[15] Seventeen passengers plus stores for the Pieman River goldfield were crammed aboard the tiny vessel, which took on further stores at Latrobe on the Mersey River during a five-day stopover. When the Amy got underway again, overloading had made it so unsteady that the bulk of the cargo had to be put ashore at the Mersey heads. Another layover occurred at the port of Stanley, in the far north-west, this time for bad weather. On the seventh day out of Launceston the steamer put in at the remote sheep and cattle station of Woolnorth, on the north-western tip, again delayed by buffeting winds, the passengers having enough time ashore to go rabbiting, inspect the bones of a stranded whale and hold a meeting in which they established their own west coast prospecting association! Reaching the Pieman River heads ten days out of Launceston brought good news —the dreaded bar was passable, for the first time in many days. So many vessels had come to grief on the Pieman River bar that a successful crossing was invariably met with an address of thanks to the captain and his chief officer and a hearty round of cheers. Passengers had time to develop an opinion on nearby gold workings before re-embarking for Heemskirk.[16]

Sections of the metalwork of the overshot waterwheel remain on site next to the Carn Brea wheelpit today. Nic Haygarth photo.

Developing the Carn Brea Tin Mine

At the inaugural meeting of the Carn Brea Tin Mining Company, held in Hobart in January 1883, Rabling was appointed mine manager and promptly adjourned to the west coast with eight assistants. While publicly, at least, Rabling made no grandiose comparisons with the Cornish tin field, he did name the mine Carn Brea, after the hill that stands over his home town, Camborne, in Cornwall, perhaps a reflection of homesickness as well as an assurance of worth to cheer the shareholders. In February 1883 Carn Brea shareholders authorised a loan to pay for a battery and a 24-foot iron overshot waterwheel manufactured at WH Knight’s Phoenix Foundry in Launceston.[17] A road had to be built to North Heemskirk before the equipment was delivered by steamer at the dangerously exposed port of Trial Harbour.[18] However, when the machinery came to be hauled up the road by horse team the carters ran out of horse feed, causing further delay.[19] When visiting the Carn Brea Mine, the Mercury newspaper’s ‘special’ reporter Theophilus Jones was only able to inspect the stone cutting and wheel pit prepared for its reception, Rabling’s 84-foot drive and 20-foot winze and a lode said to be four to five feet wide. He was reassured by the manager serving him steaming Royal Blend tea, preserved meat and ‘excellent’ bread and butter. Furthermore, Rabling had

‘pitched his camp in a snug corner formed by the junction of two banks above a small creek. He has not wasted the shareholders’ money by erecting large and substantial houses, stable and blacksmith’s shops, with a store and a post office thrown into the bargain, but has contented himself with putting up tents, and cutting chimneys and fireplaces in the bank’. [20]

The battery and a rock face that appears to have been cut away to accommodate a work site, Carn Brea tin mine. Nic Haygarth photo.

The most settled weather in western Tasmania is in February and March, but many water-powered mines found it too dry to operate in those months. April, May and the winter and spring months would normally provide abundant rainfall, but the west coast weather would then be bracing, to say the least. Rabling would have had no choice but to stay put and do his shareholders’ bidding by preparing the claim for crushing as soon as possible, much of his time being spent huddled in a sturdy tent.

The fatal first crushing

The first half-yearly meeting of the Carn Brea Tin Mining Company in July 1883 glowed with a happy anticipation. Neither the £1800 advance on machinery, nor the six calls on shares, had disturbed the shareholders’ equanimity. Stone assaying a payable 7.5 to 14% had been paddocked awaiting the crusher, demonstrating the admirable ‘energy and skill’ of the company’s mining manager.[21]

The Carn Brea was one of nine mines on the Heemskirk field to erect a battery during the boom period. In all, 75 or 80 head of stampers were raised.[22] By October 1883 Thomas Williams was ready to crush at the Orient tin mine.[23] The Cliff and Carn Brea were almost ready to crush, the Montagu and the Cumberland were erecting machinery and mine manager George Lightly of the West Cumberland was preparing to receive machinery.[24]

However, the failure of the Orient crushing one month later threw ‘a great damper … on lode tin mining at Mount Heemskirk …’[25] Confidence in the field evaporated. The Carn Brea Tin Mining Company kept going until at its second half-yearly meeting in March 1884 it was revealed that, although assay results from the first shipment of 30 bags of crushed ore were not yet available, directors regarded mining operations as a failure. Not surprisingly, expenditure due to work delays and heavy freight costs had far exceeded Rabling’s estimates. Work had been suspended, and many shares in the company had been forfeited. One of the directors, Grubb, condemned Rabling’s management, and several disputed that he had secured any tin from the mine. Eventually, shareholders voted to accept Rabling’s offer to take the mine on tribute (that is, working the company’s lease for a percentage of the value of ore won, so at no cost to the shareholders), the unknown value of the 30 bags of tin being taken as part payment for the wages the company owed him.[26] All work seems to have been abandoned soon after. No further substantial work appears to have taken place at the Carn Brea Mine.

Although Trial Harbour would enjoy a brief resurgence as the port for the Zeehan–Dundas silver-lead field, the Heemskirk tin field would never fulfil early expectations. Former Peripatetic Tin Mine manager Con Curtain estimated that at least £100,000 were spent at Heemskirk 1880–84 for a return of about 70 to 100 tons of dressed tin.[27] By 1962 total production on the field had not progressed substantially, amounting to a mere 668 tons of metallic tin.[28]

[1] Gustav Thureau, West coast, Legislative Council Paper 77/1882, p. 27.

[2] ‘Mt Heemskirk’, Mercury (Hobart), 5 October 1881, supplement, p. 1.

[3] Census for England 1851 and 1861.

[4] ‘Miss Eliza Rabling’, Cornishman, 19 January 1889, p. 2; Sharron P Schwartz, Mining a shared heritage: Mexico’s ‘Little Cornwall’, Cornish–Mexican Cultural Society, England, 2011, pp. 51–52.

[5] England and Wales Probate Calendar, 1858–1966.

[6] Rod Home, ‘Science as a German export to nineteenth century Australia’, Working Papers in Australian Studies, no. 104, London, 1995, pp. 7–11, 17.

[7] Census for England 1861 and 1871.

[8] Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, pp. 215–20; Allen Buckley, The story of mining in Cornwall, p. 140.

[9] ‘Gold news’, Launceston Examiner, 3 March 1877, p. 5.

[10] ‘Our Launceston letter’, Mercury, 4 October 1879, p. 3.

[11] Conduct record, CON37/1/11, p. 6063 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart [hereafter TAHO]).

[12] ‘Second Court’, Mercury, 28 July 1881, p. 3.

[13] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 30 August 1881, p. 3; ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 31 August 1881, p. 3.

[14] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 27 April 1882, p. 3.

[15] ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 31 August 1881, p. 3.

[16] ‘The west coast goldfields’, Mercury, 17 September 1881, p. 2.

[17] ‘Heemskirk’, Mercury, 23 October 1883, p. 3; ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 9 March 1883, p. 3.

[18] ‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 8 May 1883, p. 3.

[19] ‘Managers’ reports’, Mercury, 30 June 1883, p. 2.

[20] ‘Our Special Reporter’ (Theophilus Jones), ‘The west coast tin mines’, Mercury, 31 May 1883, p. 3.

[21] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 1 August 1883, p. 3.

[22] According to Con Curtain and LJ Smith, companies which installed batteries included the Carn Brae (JT Rabling; 10 heads, from .H Knight’s Phoenix Foundry, Launceston), Orient (John Williams; Thomas S Williams; 10, Salisbury Foundry, Launceston), Cliff (John Hancock; William Williams; W Thomas; PT Young; Edward Perrow, 5), the West Cumberland (George Lightly; 5), the Wakefield (5), Cumberland (AB Gallacher; 10), the Montagu (Alex Ingleton; 15), the Victorian-registered Cornwall Tin Mining Co (Mark Gardiner; 10, WH Knight), and Peripatetic (Con Curtain; 10). Companies which did not install machinery included the Montagu Extended (Robert Hope Carlisle), Prince George (John Addis), St Clair (James Henry Nance), Champion (WG Hensley), Mount Heemskirk and Agnew (John Greenwood), Heemskirk River (Edwin Tremethick) and the St Dizier (Nicholas St Dizier). The Empress Victoria (Thomas Fowler) had a steam hoisting plant but no treatment plant. See Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’, Examiner, 27 February 1928, p. 5; and LJ Smith, ‘South Heemskirk tin mine’, Advocate, 11 August 1928, p. 14. Curtain claimed there were 75 heads of stampers on the field, but Smith’s list of batteries added up to 80 heads.

[23] Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old Times: Heemskirk Mines and Mining’. There is a five-head battery at the Carn Brea mine today.

[24] ‘Heemskirk’, Mercury, 23 October 1883, p. 3.

[25] Editorial review of 1883, Launceston Examiner, 1 January 1884, p. 2.

[26] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 3 April 1884, p. 3.

[27] Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’.

[28] AH Blissett, Geological survey explanatory report, One Mile Geological Map Series, Zeehan, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1962, p. 112.

by Nic Haygarth | 17/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Herbert and Rosina Murray with their daughters Esma and Doreen, c1922. Courtesy of the Goddard family.

In January 1906 Herbert Villiers Murray (1892–1959) was walking from the town of Waratah to work at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, a small open cut tin mine operated by Anthony Roberts at which his brother was battery manager. Thirteen years old, he was fresh out of school. Herbert was an orphan, both his parents having died in his home state of South Australia. Since his Waratah guardian would not allow him to stay at the mine, he had no option but to tramp 8 km each day along the North Bischoff Road.[1]

Eighteen-foot-diameter water wheel and two-head battery being erected at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, North Bischoff Valley, in about 1905.

Passing the Happy Valley Face of Mount Bischoff, armed with his snake stick and crib bag, he followed the road until about 3 km further it turned into a sledge track cut for the old Phoenix battery. Rounding a spur, he saw a dog about 50 metres ahead of him, padding in the same direction. He whistled at the dog, which failed to respond as it trotted around the next spur. Herbert hurried on in his hob-nailed boots. He anticipated meeting the dog’s owner but, bafflingly, neither dog nor man came to greet him.

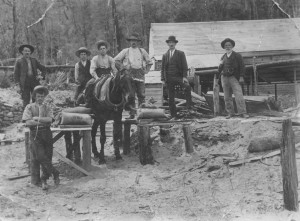

Are the Murray boys posed here on the pack-horse? This is another shot of the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise mine, with Cornish tin miner Anthony Roberts at right. Photo courtesy of Colin Roberts.

He reached the steep incline at the end of the metal road where the haulage was for the old Phoenix tin-dressing mill, then continued on along the sledge track, aware that the area was ‘the home and play-ground of a fair variety of snakes that travelled quite a lot in January and February—their mating period’. At last he came to the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise sawmill, and the plumber’s shop where the sluicing pipes were made. Had anyone seen a man or a dog? No. Herbert described the dog, and ‘to my surprise they told me that it was a Tasmanian tiger I was endeavouring to catch up to’.

In those days, herd of semi-wild goats roamed the valleys around Waratah and Magnet, sometimes being shot for their meat. Herbert wondered if a goat was the focus of the thylacine’s attention that day on the North Bischoff Road. He was not keen to be the tiger’s prey:

‘Fear must have obsessed me for I cut a much stouter snake-stick, also my eyes became more searching as each turn of the track or road came into view, also I heard many more bush noises when travelling to and from “The Valley”. My fear subsided as the days passed, yet the years and the ears were always on the alert.’

There were regular sightings of thylacines in the Waratah region at that time, especially along mining infrastructure in the bush: ‘A reliable prospector told me that he knew that four pups found in the decayed butt of a large fallen tree in the Savage River, had died from one shot from a gun, as they were of little or no value in those days’.[2] However, with scarcity the value of a live one grew. In 1925 the Waratah snarer Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray advertised his captured tiger for sale in the newspaper before delivering it to the zoo in Hobart.[3]

By then the Mount Bischoff mine was a marginal operation, the tin price was low and there was little work in Waratah. Herbert Murray had married English girl Rosina Goddard and moved to Melbourne, leaving the likes of his namesake, ‘Cutter’ Murray, and Luke ‘Stiffy’ Etchell, to extricate the occasional tiger—dead or alive—from their necker snares.

[1] See Goddard family research, ancestry.com,

http://person.ancestry.com.au/tree/408869/person/-2071601523/facts

accessed 17 December 2016.

[2] Herbert V Murray, 6 Renown Street, North Coburg, Victoria, to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, Hobart, 11 July 1957, AA612/1/59 (TAHO).

[3] ‘For sale’, Examiner, 15 June 1925, p.8.

by Nic Haygarth | 10/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history

The diversion tunnel at Mayne’s tin mine, a later development near the Orient Tin Mine.

The view of Mount Agnew from the Orient Tin Mine site, where the first west coast church and reading room stood in 1883.

In 1902 you could get a tertiary education at Zeehan, a place dominated by frogs, snakes and marsupials a dozen years earlier. The Zeehan School of Mines was affiliated with the University of Tasmania, putting it on equal academic footing. The university issued the school’s diplomas and certificates, and appointed its examiners. Subjects studied at Zeehan could be counted towards a degree from the University of Tasmania.[1]

Yet the first educational institute on the west coast was established nearly two decades earlier. It stood on the claim of the Orient Tin Mine at Cumberland Creek, near Trial Harbour. Strictly speaking, it was a Methodist church—the first church on the mining fields south of Waratah.

Travelling journalist Theophilus Jones described the site when he accompanied the Minister for Lands, Nicholas Brown, on a visit to the Heemskirk tin field in May 1883. The Orient Tin Mine was then considered the premier mine in the district. Such impressive assay values had been obtained here that the future of the Heemskirk tin field seemed assured. Anticipation was then building about the first crushing at the Orient, which would follow soon after.

Thomas Stephens Williams, manager of the Orient Tin Mine, photo courtesy of Mr Barnard.

On arrival at the mine, Minister Brown, who happened to be the chairman of directors of the Orient Tin Mining Company, was ushered into Cornish mine manager Thomas Williams’ (c1826‒1901) ‘snug little’ cottage. Here the Devon-born Fanny Williams served home-made cake and tea. The new church, built by Williams and his sons Luke and Tom from sawn timber, with a split shingle roof, and a blackwood interior adorned with chandeliers, had recently been opened with a traditional Wesleyan Methodist tea meeting. Fanny Williams and other mining folk had provided sandwiches, sponge cakes and blanc manges for the occasion.[2] (Later, a collection of books would be obtained and, with Luke Williams acting as the librarian, during week days the church would act as a reading room, like a tiny mechanics’ institute.[3]) The machinery was also impressive. A Robey And Co steam engine imported from England had been installed as an auxiliary to the waterwheel which would drive the 10-head stamper battery. Five Munday’s self-emptying concave buddles were ready for tin separation.[4] Nearby was another Cornish legacy, a grave with a picket fence which represented the final resting place of the wife of the original Orient mining manager, John Williams.[5]

The surprise failure of the Orient crushing in October 1883 threw ‘a great damper … on lode tin mining at Mount Heemskirk …’[6] Confidence in the field evaporated. Thomas Williams resigned his post, and the little church and reading room was removed. Mayne’s Tin Mine later produced 140 tons of metallic tin near the site of the Orient, showing that the area had at least limited potential.[7]

Two of Williams’ sons later followed in his footsteps. Richard Williams (c1866–1919) managed the Colebrook Mine on the west coast of Tasmania, then copper mines at Chillagoe and Cloncurry in Queensland, the Byron Reef Gold Mine in Victoria before dying at Southern Cross, Western Australia.[8] Former Orient librarian Luke Williams (c1859‒1931) became a well-known Tasmanian mine manager, operating, among others, the Mount Read Mine and the Chester Mine. The village of Williamsford was named in his honour.[9] He had a long association with Robert Sticht, general manager for the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company.

Luke Williams was innovative. Under his management, in the winter of 1917, the Copper Reward Mine at Balfour switched from raising copper underground to raising tin from the button-grassed surface. The button-grass was burnt and the land ploughed by horse-team. The loose earth was then scooped into a sluicing race, down which a horse drew a ‘puddling harrow’ (sluicing fork) to break down lumps and reduce the material to a pulp. Two dams built from button-grass sods cemented together by clay supplied a hydraulic sluicing operation which worked the lower face of the tin-bearing ground. Operations ceased when the price of tin dropped in 1921.[10] Williams died in comfortable retirement in Hobart a decade later as a well-known pig breeder and orchardist, his early efforts to enlighten the west coast having been long forgotten.[11]

[1] Patrick Howard, The Zeehan El Dorado, Mount Heemskirk Books, Blackmans Bay, 2006, pp.186‒87.

[2] ‘Our Special Reporter’ (Theophilus Jones), ‘The west coast tin mines’, Mercury, 28 May 1883, p.3;

[3] (Theophilus Jones), ‘West coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 December 1896, p.1; Luke Williams, ‘The Orient Library, Heemskirk’, Mercury, 27 September 1883, p.3.

[4] Gustav Thureau, Report on the present condition of the western mining districts, Parliamentary Paper 89/1884, p.1.

[5] (Theophilus Jones), ‘West coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 December 1896, p.1. She died in June 1882 (‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 14 June 1882, p.3).

[6] Editorial review of 1883, Launceston Examiner, 1 January 1884, p.2.

[7] AH Blissett, Geological Survey explanatory report, One Mile Geological Map Series, Zeehan, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1962, p.106.

[8] ‘About people’, Examiner, 1 October 1919, p.6.

[9] Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’, Examiner, 27 February 1928, p.5.

[10] ‘Balfour notes’, Circular Head Chronicle, 16 February 1921, p.3.

[11] ‘Mr Luke Williams’, Advocate, 29 July 1931, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 09/12/16 | Circular Head history, Tasmanian high country history

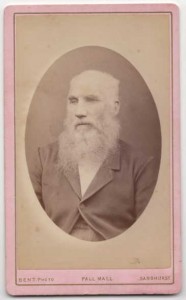

Henry Thom Sing, from the Weekly Courier, 30 May 1912, p.22.

A downtown Launceston store is the face of a forgotten immigrant success story. The building at 127 St John Street was commissioned by Ah Sin, aka Henry Thom Sing or Tom Ah Sing, Chinese gold digger, shopkeeper, interpreter and entrepreneur. He was born at Canton, China on 14 March 1844, arriving in Tasmania on the ship Tamar in 1868.[1] Sing appears to have come from to Tasmania from the Victorian goldfields, and he was quick to seize on this experience when the northern Tasmanian alluvial goldfields of Nine Mile Springs (Lefroy), Back Creek and Brandy Creek (Beaconsfield) opened up. Like Launceston’s Peters, Barnard & Co, who hired Chinese miners through Kong Meng & Co in Melbourne, Sing began to recruit Chinese diggers on the Victorian goldfields.[2] His good English skills were an asset in trade and communication, and throughout his time in Launceston his services were drawn upon regularly as an interpreter in court cases involving Chinese speakers as far afield as Wynyard and Beaconsfield.

Circular Head farmer Skelton Emmett had been washing specks of gold in the Arthur River for years before a minor rush was sparked by two sets of brothers, Robert and David Cooper Kay, and Michael and Patrick Harvey, in April 1872.[3] Within three months, 160 miner’s rights had been issued and 70 claims registered.[4]

Claims were spread over about 2 km around the confluence of the Arthur and Hellyer Rivers. The European diggers generally preferred to work ‘beaches’ in the river.[5] Two European claims, the Golden Crown and the Golden Eagle, were on the Arthur downstream of the junction. The Golden Eagle party, who included William Jones and John Durant, strung a suspension bridge consisting of a single two-inch rope across the river in order to work both banks and for easy access: effectively it was a ‘bosun’s chair’ or flying fox. They worked their claim with a sluice box and Californian pump.[6] James West and party’s claim known as the Southern Cross was in a small gully on the southern side of the Arthur. The Kays’ claim was ‘in the gulch of a ravine’ a little further inland from the river. The claim of Frank Long, who later found fame on the Zeehan–Dundas silver field, was further down the same gulch.[7] The British Lion claim of W King was at the junction of the Arthur and the Hellyer, the Harvey brothers’ claim on the Arthur above it.[8] Waters from Circular Head and a man named House also held claims.[9]

Most of the gold obtained in the area by Chinese came from working the sand bars and shallows of the Arthur River. Sing had several roles on the field. Although Seberberg & Co had also engaged Chinese diggers for Tasmania, the 50 or so Chinese at the Arthur appear to have represented only two agents, Sing and Peters, Barnard & Co, both Launceston based.[10] Because he had a Launceston business to maintain, Sing’s time at the diggings would have been limited. He appears to have had two claims which were worked by Chinese parties, and he acted as an interpreter for other parties.[11] He also bought gold from diggers.[12] In November 1872, with the river low enough to permit an attack on its dry bed, both Sing parties engaged in ‘paddocking’, that is, diverting part of or the entire stream by damming it on their claim. On the upper claim the resulting wash dirt was put through a cradle, but the eight men expected to achieve better results when their sluice boxes were complete. Likewise, Lee Hung was building a sluice box.[13] The upper party once took 10 oz of gold in a day.[14] Wha Sing’s claim on the Arthur above the confluence included a vegetable garden, which would have provided his party with both food and cash, since stores would have been at a premium on the isolated field.[15]

One of the Chinese parties was said to have ‘turned’ the Arthur River in order to work its bed. While the Arthur is a large river, this is not as difficult an undertaking as it sounds. The idea is to drive a short tunnel or channel through a hairpin bend in the river, diverting its flow. A quick scan of the map makes it obvious where this could have been done. In fact the diversion channel would not have been on the Arthur River, but on the Hellyer, just above its junction with the parent river. This ingenious method of exposing a stream bed was employed on many gold fields and in Tasmania by osmiridium miners on Nineteen Mile Creek and other places.

The largest nugget obtained by February 1873―1 oz 3½ dwts―was found by a Chinese party in the river, but, generally, bigger nuggets were taken in the creeks.[16] Frank Long claimed to have got his best gold about 10 km from the Arthur River, and his was ‘much more nuggety’ than that of James West, who worked closer to the river. The gold appears to have been patchy. All the productive claims were above that of the Kays.[17] Working the creeks was harder in summer, but diggers made up for the lack of sluicing water by using chutes to bring the washdirt to the river.[18]

The Arthur River gold field was deserted by the end of 1873, and the Chinese soon switched to alluvial tin mining in the north-east. Sing built up his Launceston business. By the time he was naturalised as a British subject in 1882, he was renting a shop and residence at 127 St John Street, Launceston.[19] In 1883 he bought the site and erected a new premises designed by Leslie Corrie.[20] Here he sold imported Chinese groceries, ‘fancy goods’, preserved fruits, silk, tobacco, fireworks and the Chinese drinks and remedies Engape, Noo Too and Back Too.[21] Sing’s residence also served as a staging-post of Chinese tin miners arriving in Launceston. In 1885 he cemented his position in the north-east by buying out the store of Ma Mon Chin & Co at Weldborough, which afterwards operated as Tom Sing & Co.[22]

While a £10 poll tax was levied on Chinese entering the colony in 1887, Launceston’s established Chinese population became part of the community, with local businessmen Chin Kit, James Ah Catt and Henry Thom Sing supporting the work of the Launceston City and Suburbs Improvement Association by staging spectacular Chinese carnivals at City Park in 1890 and the Cataract Gorge in 1891. Fire gutted the Sing premises in 1895, and as a result it was either altered or rebuilt to the design of Launceston architect Alfred Luttrell.[23] This building remains today.

Sing married twice, and fathered at least seven children.[24] Both his brides appear to have been European. His death, in May 1912, aged 68, after 44 years in the Launceston business community, passed almost without comment in the Tasmanian press, perhaps indicating that, despite his naturalisation, a racial barrier between Chinese and Europeans remained.[25] Probate valued at £1738 suggested modest success.[26] Like the former Chung Gon store in Brisbane Street, today Henry Thom Sing’s St John Street store remains part of Launceston’s commercial sector.

[1] Naturalisation application, 22 July 1882, CSD13/1/53/850 (TAHO), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=tom&qu=sing, accessed 10 December 2016.

[2] ‘New Chinese diggers’, Tasmanian, 11 February 1871, p.11.

[3] ‘Gold discoveries at King’s Island and Rocky Cape’, Cornwall Chronicle, 29 April 1872, p.3.

[4] Charles Sprent to James Smith from Table Cape, 21 July 1872, NS234/3/1/25 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

[5] ‘The Hellyer goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicle, 22 November 1872, p.2.

[6] ‘Notes on the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 20 December 1872, p.2.

[7] ‘A look round the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 3 February 1873, p.2.

[8] ‘Notes on the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 20 December 1872, p.2.

[9] ‘The Hellyer gold-field’, Cornwall Chronicle, 16 December 1872, supplement, p.1.

[10] ‘The Nine Mile Springs goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicle, 13 May 1872, p.2; ‘Chinese immigration’, Tasmanian, 18 May 1872, p.8.

[11] See, for example, ‘More gold from the Hellyer diggings’, Tasmanian, 25 January 1873, p.12.

[12] ‘Table Cape’, Tasmanian, 25 January 1873, p.5.

[13] ‘The Chinese diggers at the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 November 1872, p.3.

[14] ‘The Hellyer goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicl,e 22 November 1872, p.2.

[15] ‘The Chinese diggers at the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 November 1872, p.3.

[16] ‘The Hellyer diggings’, Mercury, 13 February 1873, p.3.

[17] ‘Table Cape’, Cornwall Chronicle, 17 January 1873, p.3.

[18] SB Emmett, ‘The western gold field’, Launceston Examiner, 1 February 1873, p.3.

[19] Naturalisation application, 22 July 1882, CSD13/1/53/850 (TAHO), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=tom&qu=sing, accessed 10 December 2016.

[20] ‘Tenders’, Launceston Examiner, 26 July 1884, p.1..

[21] ‘Law Courts’, Tasmanian, 26 May 1883, p.563.

[22] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 19 September 1885, p.1.

[23] ‘Tenders’, Launceston Examiner, 7 March 1895, p.1.

[24] ‘Deaths’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1882, p.2; marriage registration no.966/1884, https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=henry&qu=thom&qu=sing#; accessed 10 December 2016.

[25] ‘Deaths’, Weekly Courier, 30 May 1912, p.25.

[26] Will AD96/1/11, LINC Tasmania website, accessed 10 December 2016.