To Lake St Clair with car and camera

Starting out from the Ouse River in the Hupmobile, 1914-15 trip. Ray McClinton photo from the Weekly Courier, 28 January 1915, p.18.

It was the first motor trip to Lake St Clair. In 1915 pioneering motor tourers Ray and Edith McClinton mounted a two-week expedition from Launceston to the highland lake, with ‘Nina’, social pages and women’s editor of the Weekly Courier newspaper, as their guest. The Hupmobile party, towing an additional 120 kg of motor boat engine and luggage, battled rocks, ruts, rain and button grass up the Derwent Valley, breaking their trip at Ouse, the Ellises’ house near the Dee River, Weeding’s at Marlborough and Pearce’s at the Clarence River.[1]

McClinton, a San Francisco dentist who with his wife lived in Launceston 1904–28, would soon become one of Tasmania’s great tourism ‘boosters’.[2] Like fellow Launceston rev-heads Stephen Spurling III, Fred Smithies and HJ King, McClinton worshipped both nature and technology. He wanted to crash deep into the highlands, breaking down the physical and virtual isolation with carburettors and cameras. He was also imbued with fervour for worthy objects and the nineteenth-century tradition of public education that made him a consummate lantern slide lecturer on anything from x-raying teeth to colour photography.[3] Soon he would turn those skills to promoting Tasmania’s scenic wonders. Visiting Lake St Clair was one of the foundation stones of his eventual campaign in support of plans for a Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair national park.[4]

The Hup party at the government log cabin, Cynthia Bay, Lake St Clair, 1914-15 trip, with the unmistakable figure of Paddy Hartnett closest to the camera. Ray McClinton photo from the Weekly Courier, 28 January 1915, p.18.

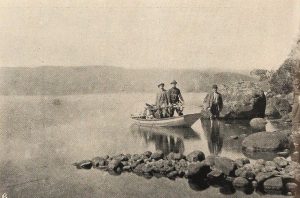

The motorboat and Paddy Hartnett in the lake, 1914-15 trip. Ray McClinton photo from the Weekly Courier, 28 January 1915, p.18.

Already there was rudimentary infrastructure at the lake. The Hup party took advantage of the government-built three-room log cabin at Cynthia Bay. On foot at last they crossed the Cuvier River on a rustic bridge. McClinton attached his engine to the boat at the lake, enabling communication with the Perrin party —a pedestrian party—camped near the Narcissus at the northern end of the lake. Highland guide Paddy Hartnett had led them to Lake St Clair via the Mersey River.[5] ‘Nina’ marvelled at the reflections in the Narcissus River and the gambolling of a platypus. She made even the ‘perfume of petrol’ mingle poetically with the ‘sweet scent of the woods’, as the first propeller churned the waters of Lake St Clair. A storm disrupted the return journey down the lake but, with the aid of axe, saw, lamp and candles, McClinton soon fashioned ‘Nina’ a comfortable bower in the forest:

‘Imagine myrtle trees towering over a hundred feet high, and their branches interlaced, so that only patches of sky could be seen above, and only glimpses of the lake between. Then picture tree-ferns all around, and green moss for a carpet. Add to his a vision of remnants of fallen trees of age untold, coated with moss inches thick, like green plush. The imagine crystal streams trickling down the mountain side … The whole scene was fairyland …’[6]

But who was ‘Nina’? She was an outstanding journalist called Kate Farrell, better known by her pseudonyms ‘Nina’ and ‘Sylvia’. Her literary career spanned 33 years and included both Launceston dailies, the Daily Telegraph and the Examiner, plus their respective weekend newspapers, the Colonist and the Weekly Courier.[7] The scale of her anonymity can be tested quite easily by searching the Trove digital database: during her literary career c1894–1927 the name Kate Farrell has only 7 hits, while ‘Woman’s World’ by ‘Sylvia’ occurs 1933 times.[8] ‘Woman’s World’ was generally frocks, recipes and home hints. In 1914 Farrell published her 96-page Sylvia’s cookery book.[9] During World War One she turned her attention to bringing comfort to those at the front, and she was also a ‘booster’, penning tourist guide The charm of the north in 1922.[10] Farrell had been motor touring with the McClintons for years, having accompanied them to Lake Sorell in their Winton Four and on Edith McClinton’s one-woman non-stop run from Launceston to Richmond in the Hupmobile. [11] Farrell preceded Ray McClinton as a tourism ‘booster’, and at Lake St Clair she quickly got into her stride:

‘The beauty of the scene is inexpressible. One can imagine the crowds of tourists who would visit Lake St Clair if the road were made. A number of small chalets built, with a caretaker in charge, and a motor boat available for the use of visitors, would help matters along considerably. I hope it will not be long before such dreams come true’.[12]

Stuck in a wash-out near Ellendale, 1916-17 trip, King and McClinton in action. HJ King photo courtesy of Daisy Glennie.

The Hupmobile, containing the two ladies, and McClinton in the ‘Baby Grand’ Chevrolet, posed as if tackling the corded track, 1916-17 trip. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

‘The darkroom at Lake St Clair’, HJ King despairs over the photographic facilities, 1916-17 trip. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

The 1916-17 party at Bushy Park, Sir Philip Fysh with the white beard, the McClintons at centre, with Kate Farrell fourth from left. Bushwalker and park administrator WJ Savigny is second from left. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

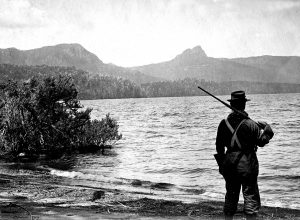

The McClintons and Farrell repeated their Lake St Clair excursion two years later, this time with the established amateur photographer HJ King. While King drove McClinton’s faithful old Hupmobile (registration number 586), the dentist was at the helm of his new ‘Baby Grand’ Chevrolet (number 4465). Both vehicles survived—but, in the true tradition of motor touring, it was a near thing for much of the way. The government accommodation house had been destroyed by fire in the intervening two years. However, rather than repeat herself, Farrell minimised her tourism boosting and concentrated on describing the route taken and the social pleasantries of a visit to former premier Sir Philip Fysh’s Bushy Park estate.[13] The real reporter was King. McClinton deferred to the superior shutterbug, allowing him to be the official tour photographer, and many King photos from this trip appeared in the Weekly Courier during 1917, including his light-hearted ‘Lake St Clair Darkroom’.[14] King’s keen eye captured the logistical difficulties of the corrugated track, with block and tackle deployed near Ellendale, some pick and shovel work on the Sandhill at Lawrenny and rescue by a bullock team near Derwent Bridge. McClinton also appears to have had a long stint with a hand saw clearing a fallen tree. One of the most interesting images from the trip was McClinton, the ex-patriate American, recalling his military training by posing with a gun upon his shoulder, as if guarding the beauty of Lake St Clair.[15] How far they were from the European War (King was a conscientious objector, McClinton effectively neutral), yet the connection remained even here.[16]

Ray McClinton posed militarily in front of Mount Ida, 1916-17. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

‘To Lake St Clair with car and camera’ became one of first outings of the McClinton–King lantern lecturing team.[17] Later, with Fred Smithies, they would add Cradle Mountain and the Pelion region to their lecturing repertoire. At her retirement in 1927 Kate Farrell was ‘Launceston’s senior press woman’ and the last of the Weekly Courier’s original staff. [18] The McClintons were there to farewell her, just ahead of their departure from Tasmania.[19] Farrell died in 1933, after a long battle with illness, leaving only King to enjoy the road they had craved, the ‘missing link’—forerunner of the Lyell Highway—between Marlborough and Queenstown.[20] By then Lake St Clair was well on its way to becoming a tourism hub.

[1] See ‘Nina’ (Kate Farrell), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Weekly Courier, 21 January 1915, p.29; 28 January 1915, pp.27–28; 4 February 1915, pp.28 and 29; and 11 February 1915, p.28.

[2] Edith McClinton actually left Tasmania for Honolulu in June 1927 (‘Social notes’, Daily Telegraph, 22 June 1927, p.2), Ray MClinton joining her there in November 1928 (‘Dr Ray McClinton’, Mercury, 8 November 1928, p.11).

[3] See, for example, ‘X-rays and the teeth’, Examiner, 18 June 1925, p.5.; and ‘Local and general’, Daily Telegraph, 5 July 1923, p.4. For Launceston rev-head photographers generally, see Nic Haygarth, The wild ride: revolutions that shaped Tasmanian black and white wilderness photography, National Trust of Australia (Tasmania), Launceston, 2008.

[4] McClinton and Smithies had visited the Du Can Range area in 1913, and may have visited Lake St Clair at that time, but that was a pedestrian trip.

[5] See ‘The adventures of Paddy’s Gang: an account of a Perrin family trip to Lake St Clair guided by Hartnett over the Christmas–New Year period in 1914–1915’, diary in possession of Bessie Flood.

[6] ‘Nina’ (Kate Farrell), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Weekly Courier, 28 January 1915, p.28.

[7] ‘Miss K Farrell’s death’, Examiner, 4 July 1933, p.9. Thanks to Ross Smith for identifying ‘Nina’.

[8] The Weekly Courier is not yet indexed on Trove, making it impossible to search on ‘Social notes’ by ‘Nina’. Propriety of the time contributed to this disparity, insisting that she be referred to simply as ‘Miss Farrell’ throughout her life.

[9] ‘Social notes’, Daily Telegraph, 25 May 1927, p.2. The full details are K Farrell, Sylvia’s cookery book: tested recipes and items of interest, Launceston, 1914.

[10] K Farrell, The charm of the north, Launceston City Council, Launceston, 1922.

[11] ‘Nina’ (Kate Farrell), ‘Camping at Interlaken’, Weekly Courier, 21 January 1909, p.29; ‘Exhaust’, ‘Motor notes’, Daily Telegraph, 9 November 1911, p.11.

[12] ‘Nina’ (Kate Farrell), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Weekly Courier, 11 February 1915, p.28.

[13] ‘Nina’ (Kate Farrell), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Weekly Courier, 11 January 1917, p.27. The trip was also written up by ‘Spark’ (Charles George Saul), ‘Motoring’, Examiner, 13 January 1917, p.4. Thanks to Ken Young for identifying ‘Spark’.

[14] See Weekly Courier, 11 January 1917, p.17; 18 January 1917, p.18; 25 January 1917, p.17; 1 February 1917, p.17; 15 February 1917, p.17; 22 March 1917, p.20; 5 April, pp.17, 20 and 21; 31 May, p.21; 13 September, p.17; 18 October 1917, p.17; and 1 November 1917 (Christmas issue), p.22.

[15] Ray McClinton performed military training 1900–02 in California, film no.981549, MF4:2, National Guard Registers v.61, 1st Infantry, 2nd Brigade, Enlisted Men, 1883–1902, California, Military Registers, 1858–1923.

[16] McClinton supported the Allied war effort, but America did not enter World War One until April 1917.

[17] See ‘Spark’ (Charles George Saul), ‘Motoring’, Examiner, 3 February 1917, p.4; ‘Plug’, ‘Motor notes’, Daily Telegraph, 13 February 1917, p.6.

[18] ‘Journalist honoured’, Examiner, 24 May 1927, p.7, ‘Social notes’, Daily Telegraph, 25 May 1927, p.2.

[19] The McClintons’ names were accidentally omitted from the Examiner’s story of this event. See the correction, Examiner, 25 May 1927, p.7.

[20] ‘Miss K Farrell’s death’, Examiner, 4 July 1933, p.9.