The roadrunner: William Byrne, mining fields mailman. Part Two: The West Coast mail.

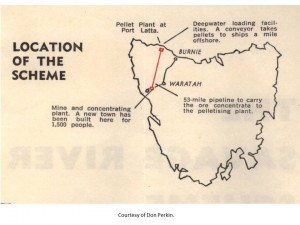

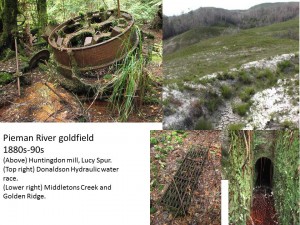

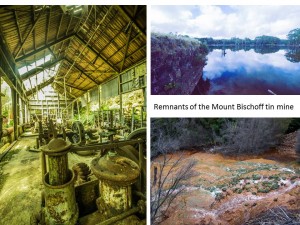

In the story ‘An “island” within an island: the maritime/riverine culture of Tasmania’s Pieman River goldfield 1877–85’, I discussed how that goldfield was virtually an island within the island of Tasmania, in that it was remote, served almost entirely by sea, took sustenance from the waterways and used them for transport.[1] The telegraph reached Corinna in 1879 but for years the only other land service was the mail run from Waratah.

The mailmen were roadrunners, men compelled to walk and run—whatever it took to make up lost time—the godforsaken track on the Bischoff–Heemskirk–Pieman service. Imagine your business dealings or your affairs of the heart hinging on news that takes ten days between destinations—and there is no resort to telephone or email should that vital letter disappear in transit, as it so often did.

Estimates of William Byrne’s mileage as West Coast postman mounted impressively during his career: 32,000 by 1884, 38,000 by 1886, more than 40,000 by 1887 and 43,000 (about 69,000 km) by the time of his death in 1911.[2] By the mid-1880s the weight on his back, and perhaps sheltering in the hollows of trees, had left him ‘slightly stooped’, but it is a wonder that wasn’t the least of his physical ailments.[3] Because the West Coast mailman never rested, battling the elements in all seasons.

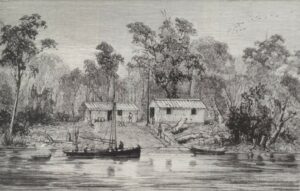

The Government Store at Corinna, on the Pieman River. Sketch by O Jarman, from the Tasmanian Mail, 14 May 1881.

A sketch of the old Trial Harbour Post Office, at the

Montagu Mine, South Heemskirk tin field.

Mine manager Alex Ingleton served as the postmaster.

From the Tasmanian Mail, 11 September 1913, p.23.

How Heemskirk was left in the dark

After losing the Bischoff mail service, Byrne won the contract for the far more strenuous one between Mount Bischoff, the Heemskirk tin field and the Pieman River goldfield. This would have meant finding accommodation at Waratah. The hazards associated with delivering the mail on time included the VDL Co service arriving late into Waratah, fallen trees, flooded streams, broken bridges and sunken rowboats. The journey was by foot, since the track cut by local subscription between Waratah and the Middleton Creek diggings near the Pieman was not fit for a horse.[4] It included the infamous ‘Underground Railway’, a stretch of almost a mile which compelled users to crawl under burnt spars.[5]

The remaining stamper battery at the Carn Brea Tin Mine near Granite Creek, Heemskirk. Nic Haygarth photo.

The Peripatetic Tin Mine stamper battery standing outside the Trial Harbour History Room. Nic Haygarth photo.

Yet it was on this track that Byrne earned his reputation as an indomitable marathon runner, setting a cracking pace in order to meet his deadline. He became famous for sleeping in hollow trees and carrying only blankets for bedding—no tent or tent fly, not even so much as a change of clothes. Arriving at camp, he would dry himself by the fire and retire to his blankets.[6] He had camps—hollow trees—at the Whyte River and Long Plain, but his favourite hollow tree was on the Magnet Range.[7] In this hollow it was said that, with his belly full of Waratah rum, he would lighten his load by stashing newspapers according to his unique system of dispensing social justice. A Heemskirk resident accompanying Byrne across the Magnet Range once witnessed the mailman take no less than 73 newspapers from the hollow tree—seventeen of which were addressed to the witness. When asked about the newspaper stash, Byrne

‘replied that he could not see why people required so many newspapers, and he made a point of here sorting them over, according to the several merits of the persons to whom they were directed. First some were directed to a Frenchman, who could not read English, and what good could newspapers be to him. They went into the tree. Next, others were directed to a man who was half blind, and reading could only injure his eyes; tree again. In the third case, newspapers were directed to a man who could not see at all; tree again, as a matter of course’.[8]

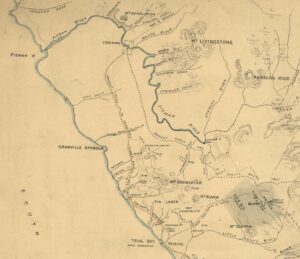

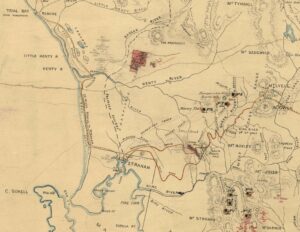

A crop from George Lovett’s 1888 exploration chart showing the track from Corinna on the Pieman River to the Heemskirk tin field, including Climie’s Track (the coastal route) used by the mailman and the Montagu Tin Mine above Trial Harbour (Bay). Cropped from AF395/1/29 (TAHO).

When in 1879 the Pieman overtook Heemskirk as a mining centre, the order of delivery was reversed—Pieman first, then onto Heemskirk. In order to service the separate goldfields on the Savage and Donaldson Rivers, Byrne had to increase his pedestrianism from the contracted two visits per month to three. River crossings were a trial. If a river was flooded his options were to fall a tree or wait for the water to subside: on one occasion the Whyte River detained him for four days.[9] For crossing the Pieman, Byrne kept a rowboat chained to a tree inside the mouth of the Savage River. He once had to fetch it down from a fork in a high tree, where it had been deposited by rising waters.[10]

Tengdahl sails into the mail run

After two years on the Pieman/Heemskirk run Byrne lost the contract—allegedly because he mistakenly tendered a price for three years instead of the required one.[11] The new mailman was well-known prospector Axel Tengdahl (1853–1919), and the successful tender £156.[12] The Swede had entered west coast lore in 1879 when he and Harry Middleton sent 250 diggers splashing in the gold-laden Middleton Creek, on the Pieman River goldfield.[13] The discoverers probably felt fortunate to be there. Tengdahl, an old salt, had ensured their safe arrival from Launceston by spontaneously piloting the steamer Sarah over the dreaded Pieman River bar.[14] These skills should have put him in good stead for the regular river crossings on the mail run.

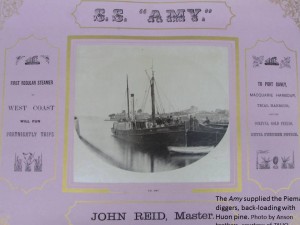

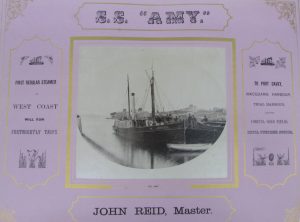

An 1881 advert for the Amy’s West Coast service to Corinna and Trial Harbour, from the Anson Brothers’ Just the thing album (no.2), LPIC14/1/46 (Libraries Tasmania).

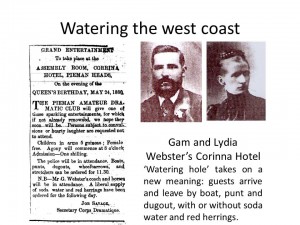

Tengdahl had tent camps at the Thirteen Mile (near the site of the later Heazlewood village) and Long Plain (near the latter-day Savage River township)—luxury by Byrne’s standards. The pedestrian mail service must have been exhausting. If the track wasn’t bad enough, the volume of mail was increasing, the weight of the consignment reaching about 28 kg in August 1881.[15] A regular West Coast shipping service was established in September 1881 when the steamer Amy began visiting the Pieman and Heemskirk every ten days—but this was only considered a supplement to rather than a replacement for the marathon mailman.

Meanwhile, Byrne would have been able to leave his Waratah lodgings and return full-time to the farm on Mooreville Road behind Burnie, his swag laid to rest for two years at least.

Byrne returns as sub-contractor for Gaffney and Harvey

In December 1881 James Gaffney and Frank Harvey, Waratah butchers, building contractors, billiard hall and store proprietors, continued their rapacious expansion.[16] The contract for the Heemskirk and Pieman mail service would have fitted in well with their stores at the 20-Mile (Long Plain) and Corinna and their maintenance contract for the track to Corinna.[17] Gaffney carried the mail himself for a time, before summoning Byrne as a sub-contractor.[18]

As the weight of his load grew, Byrne extended his war on newspapers to include parcels. When someone at the Pieman or Heemskirk ordered books from a Hobart store he refused to carry the parcel without payment of a five-shilling surcharge.[19] Perhaps some of the standard mail was also disappearing into his unofficial post office on the Magnet Range, since one man complained that ‘scarcely one half of the number [of letters] posted to him … ever reached him’.[20]

After the Brown Plain rush of 1882, the Pieman River goldfield was in the doldrums. However, in April 1883, when the Amy was replaced on West Coast service by the Wakefield, the Heemskirk hard rock tin boom was at fever pitch. Nine mines equipped themselves with crushers, 75 or 80 head of stampers being erected across the field.[21] The low yield from the first crushing at the Orient Tin Mine in October 1883 put a great dampener on proceedings.[22] Confidence in the field evaporated, and the focus of attention changed to the Mount Lyell goldfield.[23]

A crop from George Lovett’s 1888 exploration chart showing the track from Trial Harbour (Bay) across the sand dunes to Strahan. Cropped from AF395/1/29 (TAHO).

The Bischoff to Strahan Mail

Heemskirk residents presented Byrne with a gold watch at the end of his contract in September 1883, as thanks for ‘energy displayed in carrying mails from Mount Bischoff to Heemskirk’.[24]

However, that was not a retirement gift. Byrne’s final mail service was the run via the Pieman and Heemskirk to Strahan 1884–87. In 1884 Gaffney and Harvey began to re-establish themselves as storekeepers, hoteliers and general contractors at Long Bay (West Strahan), Macquarie Harbour, anticipating that this would become the port for the Mount Lyell gold (and later copper) field. They presumably had no interest in the new Waratah–Heemskirk–Strahan–Long Bay mail contract other than receiving their own mail. In December 1884 Byrne won the three-year contract for £295, that is, about £98 per year.[25] Why so cheap? In 1880, after all, Tengdahl had successfully tendered the Heemskirk contract with £156. Perhaps it was envisaged that the mailman would take a ship from the Pieman to Trial Harbour, thereby reducing his legwork. Government-provided traveller accommodation along the route would have obviated Byrne’s need of hollow trees: there were huts at the Thirteen-Mile (near the site of the later Heazlewood village), Eighteen-Mile (near the Heazlewood River), and the so-called Bauera Hut (between Long Plain and Browns Plain), about 25 miles from Waratah.[26]

However, most of the same problems obtained as before. The track was a sea of mud covered with fallen trees. Byrne would have been used to dealing with the Pieman, and the other major obstacle—the Henty River—had a ferry service, but the Tasman River was also known to flood. On one occasion the rowboat at the Little Henty lay at the bottom of the river.[27] Such unavoidable delays were not taken into account when Byrne was fined for breaches of contract.[28]

The mail service graduates to pack-horse

In 1887 new tenders were called for the Strahan mail contract—the successful mailman being required to provide a weekly service by pack-horse. Byrne would have found the new ways restrictive. New mailman WH Cole revealed that it was now impossible to lighten the load as the ex-mailman had done, since bags were sealed before he received them and each contained a list of contents.[29] Thus was Byrne’s personal post office on the Magnet Range consigned to history.

The insistence on pack-horse transport reflected increasing demand for an up-to-date service but not, unfortunately, improved infrastructure. In October 1889 mailman John Mayne described negotiating slippery corduroy (logs embedded in the ground as a track surface) and waist-deep mud between Waratah and the Pieman. A punt now existed at Corinna, but dangerous bridges, sand, bogs and onerous river crossings made the trip to Strahan ‘one of the most miserable tramps in Tasmania’.[30] It took extension of the VDL Co’s railway to Zeehan in 1900 to alleviate the mail misery.

Byrne was said to have suffered no ill effects from his marathon efforts, returning to his farm, devoting himself to the Roman Catholic Church and attaining the advanced age of 83.[31] Dodge the Hiluxes on Climies’ Track today, and across the exposed moors you might hear the Roadrunner’s footsteps echoing where rain, sleet and hail still hold court–but more likely it will just be your knees knocking together, or the hammering of a geological pick on some old Heemskirk tourmaline.

[1] See Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.10, October 2012, pp.55–71, https://www.mininghistory.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/5.-Haygarth.COMPLETED5.Vol-10.compressed.pdf, accessed 2 October 2020.

[2] ‘Shaughraun’, ‘Notes off and on’, Launceston Examiner, 17 May 1884, supplement, p.1; ‘The overland route to the Mount Lyell goldfields’, Launceston Examiner, 4 September 1886, p.3; ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 30 August 1887, p.2; ‘Passing of a pioneer’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 June 1911, p.2.

[3] ‘Shaughraun’, ‘Notes off and on’, Launceston Examiner, 17 May 1884, supplement, p.1.

[4] See ‘Mount Bischoff’, Launceston Examiner, 18 July 1879, p.3; and ‘Gossan’, ‘Burnie to Corinna’, Examiner, 29 June 1900, p.7.

[5] See ‘The West Coast to Bischoff’, Tasmanian Mail, 26 March 1881, p.3.

[6] ‘Remarkable endurance’, Examiner, 10 June 1911, p.7.

[7] ‘A Traveller’, ‘From the Pieman to Bischoff’, Mercury, 16 October 1880, supplement, p.1.

[8] ‘Enquirer’, ‘Notes from North Heemskirk’, Mercury, 17 June 1882, p.2.

[9] ‘Tasmanian telegrams’, Mercury, 13 May 1879, p.2.

[10] ‘A Traveller’, ‘From the Pieman to Bischoff’, Mercury, 16 October 1880, supplement, p.1.

[11] ‘Mount Bischoff’, Mercury, 13 January 1881, p.3.

[12] ‘The Gazette’, Mercury, 29 December 1880, p.2.

[13] Glyn Roberts, The role of government in the development of the Tasmanian metal mining industry: 1803–1883, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, Hobart, 1999, p.101.

[14] CJ Binks, Pioneers of Tasmania’s West Coast, Blubber Head, Hobart, 1988, pp.100–01. For his death, see ‘Death of Mr Axel Tengdahl: a pioneer of 1878’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 7 September 1919, p.2.

[15] ‘Tasmanian telegrams’, Mercury, 30 August 1881, p.2.

[16] For Gaffney and Harvey see Nic Haygarth, ‘Frontiersmen five: the Gaffney brothers, building, supplying and hosting Tasmania’s west coast mining fields’.

[17] ‘Official notices’, Launceston Examiner, 14 December 1881, p.3; ‘The Corinna goldfield’, Mercury, 21 January 1882, supplement, p.1; ‘Long Plains’, Tasmanian, 2 September 1882, p.973; ‘Long Plain’, Mercury, 21 October 1882, p.1; ‘West Coast notes’, Tasmanian, 10 June 1882, p.632; ‘Gazette notices’, Launceston Examiner, 26 June 1883, p.3.

[18] ‘Corinna goldfield’, Mercury, 21 January 1882, p.1; ‘The Rambler’, ‘North Heemskirk notes’, Mercury, 18 November 1882, p.3.

[19] ‘The Rambler’, ‘West Coast notes’, Mercury, 26 September 1882, p.3.

[20] ‘Visit of the Hon the Minister of Lands and Works to North Mount Heemskirk’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1882, p.3.

[21] See Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’, Examiner, 27 February 1928, p.5; and LJ Smith, ‘South Heemskirk Tin Mine’, Advocate, 11 August 1928, p.14.

[22] Editorial review of 1883, Launceston Examiner, 1 January 1884, p.2.

[23] For the Heemskirk hard rock tin boom, see Nic Haygarth, ‘”Cornwall of the Antipodes”: the “Cornish” tin boom at Mount Heemskirk, Tasmania, 1881–84’, Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.15, October 2017, pp.65–80.

[24] Richard Hilder, ‘Among the pioneers of Emu Bay: a character sketch of Mr William Byrne’, Advocate, 2 April 1925, p.2.

[25] ‘Conveyance of mails’, Tasmanian News, 16 December 1884, p.2.

[26] ‘The West Coast’, Mercury, 19 January 1882, p.1; ‘The Corinna goldfields’, Tasmanian, 12 August 1882, p.885; ‘Shaughraun’, ‘Notes off and on’, Tasmanian, 17 May 1884, p.15; ‘West Coast notes’, Daily Telegraph, 3 June 1887, p.3.

[27] ‘Prospector’, ‘West Coast mails’, Daily Telegraph, 16 August 1887, p.3.

[28] ‘Tasmanian telegrams’, Mercury, 28 November 1887, p.3.

[29] WH Cole, ‘West Coast mails’, Mercury, 3 November 1888, p.3.

[30] John M Mayne, ‘Main road to West Coast’, Tasmanian, 12 October 1889, p.14.

[31] ‘Remarkable endurance’; Richard Hilder, ‘Among the pioneers of Emu Bay’.