The rapaciousness of the Circular Head timber industry was captured in Bernard Cronin’s novel Timber Wolves, published in 1920, the year before the establishment of the Tasmanian Forestry Department in an effort to make the industry sustainable. Mainland timber contractors and local operators tried to squeeze out competitors by securing strategic leases in front of existing working leases, cutting off transport routes and making expansion impossible:

‘Did you ever hear of “dummying”? These timber wolves go to the limit [of their timber quota] in their own names and put up dummy agents to cover the rest. It’s illegal, but what does that matter. They’s [sic] no one ever asts [sic] the question so long as the rental and royalties and so on are paid regularly. The while system is rotten to the core … We got to take the price they offer us, or let the timber rot …’[1]

Conservator of Forests Llewellyn Irby read Timber Wolves before visiting Smithton in 1922. ‘This is the worst place in Tasmania for toughs’, he wrote

and is part of the locality referred to in ‘Timber Wolves’ so you can imagine what we have to deal with. We have had a lot of trouble with a chap who is the worst scoundrel in the district. He has the reputation of being a man eater, has nearly killed two men by kicking them when down, while two or three others go through life minus half an ear, a piece he has bitten off.

This was Bill (William Henry) Etchell, whom Phil Britton described somewhat tactfully as ‘a notorious strong man, opportunist leader of men, hard drinker’. According to Phil, Etchell would pay his men well, then win back much of their wages in card games at the pub. Irby feared stronger tactics:

As he was looking for me I felt a tingling in my ears and as when drunk he is absolutely murderous and we had seized his logs; I carried my gun … if they are the ‘Timber Wolves’ we are the forest bloodhounds and intend to clean them up …[2]

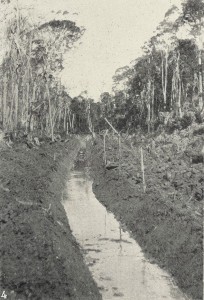

Nor were rough tactics restricted to sawmillers. By 1921 the success of the Mowbray Swamp reclamation had convinced the government to drain the Welcome, Montagu, Brittons and Arthur River Swamps. The Surveyor-General stressed the importance of reclaiming

a large area of swamp lands, now lying in useless waste, but which when reclaimed and opened up will form one of the largest and best agricultural and dairying propositions in the state.[3]

Disappointment followed. The development of the Smithton dolomite Welcome Swamp near East Marrawah (Redpa) was a comparative disaster. Drainage was inadequate, the scheme was extremely expensive, and superintendent of the works, Thomas Strickland, faced accusations of foul play. Strickland resigned with the job incomplete after being criticised by a Royal Commission into the reclamation scheme.[4] For years afterwards no land on the Welcome Swamp was ploughed.

The summer of 1923–24 was so wet that it was impossible to haul logs out on flat land by bullock team, reducing productivity, but by February 1924 the bush was drying out. ‘We may have to get a bullock driver ourselves’, Mark Britton told Jim Livingstone, ‘as you cannot depend on CW [Charlie Wells] …’ Wet weather also prevented laying down more tramway, so the chance was taken to overhaul the locomotive instead. With blackwood hard to remove from the bush, attention was switched to cutting hardwood from Robinson’s land, where tracks were opened up for the winder to work. Brittons also applied to remove blackwood from a block of crown land which they believed could only be reached by log hauler from spur lines on their own lease. At least £30 of work was done in anticipation of gaining the lease—only to discover it had been granted to Frank Fenton, one of the sons of CBM Fenton and a grandson of James Fenton, pioneer settler at Forth. He was a new player in the timber game who had built a steam sawmill at the foot of the Sandhill. Mark Britton continued:

We do not know if Fenton knows about it [the blackwood on his lease] anyway we do not intend to tell him at present … some of the mills are going bung around here and more will follow we are thinking soon.[5]

To Mark, as he explained to Llewellyn Irby, this was a clear case of dummying by Fenton. He went on to explain that there was no longer enough timber on Crown land to keep a small mill cutting for three months of the year. Brittons could have attacked the disputed blackwood by steam hauler. Fenton could not, making it impossible for him to obtain the whole of the timber.[6] Not only would timber be wasted, Mark claimed, but Fenton’s method of removing the timber could destroy roads designed for lighter traffic and built by men working legitimately.[7]

As Mark complained, by October 1925 Brittons were watching blackwood logs that they themselves had felled being removed by Fenton to his mill, using tracks they had cut and cleared:

Does your department allow such proceedings if not to whom must we apply for justice please reply at once re the matter, we do not want those tracks cut up and if your department is not responsible we will take proceedings ourselves.[8]

In truth, this was a case of Brittons letting an opportunity slip. The Forestry Department had advised the company to take up the lease, but they did not see its value, as Phil Britton remembered:

I blamed myself too, as I was told to have a look at it which I did, but not having the knowledge of assessing the volume of timber let the offer slip.[9]

Fenton saw its worth. He applied for the area, built a steam sawmill at the foot of the Sandhill and added to his holdings another 15,000 acres held by Chapman, a clerk for Cumming Bros in Burnie. He built a tramline to this new area but cleaned up the handy timber at Christmas Hills with trucks and Aub Sheen’s horse team:

Wet or fine those logs kept coming into Frank Fenton’s mill. Hazel Jacklyn was the steam engine man who kept the steam up and sharpened the circular saws. A twin sawmill and breast bench and docker were common in those days and turned out large quantities of furniture boards and flooring, all quarter cut and racked and held in stock till the Depression passed.[10]

Fenton would be the only sawmiller to beat the slump of the mid to late 1920s.

Bill Etchell was another who gave rival sawmillers a run for their money. In the early 1920s he ran out of logs on private property at Christmas Hills. He moved his portable steam engine and spot sawmill to Edith Creek, and in October 1924 relocated again, this time at the Salmon River to exploit the stands of blackwood in that area. At that time hardwood was almost unsaleable, whereas there was a strong market for blackwood.[11]

Etchell was in the habit of applying for large timber leases in front of another sawmiller, cutting off his future supply. After moving his mill, in March 1925 Etchell applied for and won a lease beyond where Brittons were working at Edith Creek. Mark Britton complained that his company should be given preference in this area,

seeing that we have opened up the way to obtain the timber having spent the best part of our time and money in the venture and then to find ourselves outdone by what appears to us speculators and adventurers that just take up areas wherever they see a blank space on the chart …

Mark pointed out that the Edith Creek mill to which Etchell was supposed to be going to mill the timber was now at the Salmon River. Anyone acquainted with the rough country concerned, Mark claimed, ‘would realise the absurdity’ of trying to build a tramway into it, although, apparently, the timber on it would have been accessible from Brittons’ existing tramway network.[12] Brittons won out on this occasion.

Careful assessment of costs had to be made ahead of taking up a permit, taking into consideration the cost of constructing and maintaining tramways and haulage. By December 1925 Brittons had cut all the blackwood on their leases with the exception of an 800-acre lease and were looking for new leases.[13]

A consummate ‘land shark’: Major Musson

Tasmania was in a perilous economic state during the 1920s. As well as sawmillers, many farmers, including returned soldiers, struggled for survival. The Primary Producers’ Association (a forerunner of today’s Tasmanian Farmers and Graziers’ Association) was established to lobby politicians about the needs of farmers.

However, not everyone was on the side of the farmer. Major Richard William Musson (not to be confused with promoter of the pulp and paper mill at Burnie, Gerald Musson) first appeared in Tasmania in December 1922 as a representative of ‘one of the leading insurance businesses’. He was noted as ‘a singer of great repute, well known in Manchester’, and had been a member of the Welsh Fusiliers during World War I.[14] The businesses he was involved in included the Flax Corporation of Australia, the Renown Rubber Ltd, the Rapson Tyre Company and the Primary Producers’ Bank of Australia, which opened its first branch at Wynyard in December 1923 before extending its custom across the state.[15] In the years 1923–25 Musson lived in Wynyard, demonstrating his talent for instant rapport by being elected president of the Wynyard Football Club and a vice-president of the Wynyard Homing Society. In February 1924 he and an associate were reported to be undertaking successful negotiations with farmers in the Marrawah district, his aim being, apparently, ‘to give the best advantages to primary producers’.[16]

Lorna Britton recalled Elijah and Mark Britton losing a great deal of money by signing up for one of Musson’s schemes, presumably the Primary Producers’ Bank. She believed that they were susceptible to cultured English accents like Musson’s. His sales pitch began by giving Lorna a pair of spurs

which he said had served him well during World War I, when he rode his trusty steed into the thick of battle in France. He said they were spurs of pure silver, but I never used them, and they have since disappeared. What use could I have had for such a cruel method of getting more speed out of poor Old Nag, who did her best with only a twitchy stick as an urge. He was a huge man, and even brought his wife with him on one occasion out through the muddy road astride a pair of horses. He used all the charismatic charm, playing the piano and singing. One favourite was ‘The Mountains of Mourne’, which he sang with such fervour that the mountains really did ‘sweep down to the sea’. He wooed the brothers so they signed eagerly on the dotted line, which cost them a great deal of money, and Mother shed many tears.[17]

Frank Britton, nine years younger than Lorna, remembered things a little differently, with Musson driving a big flashy car which, because of the muddy track, could only visit Brittons Swamp in the summer. Musson was, according to Frank,

instrumental in taking Dad down for a lot of money, with a lot of bogus companies. And the old Primary Producers’ Bank of course which was paying interest on current account that Dad never ever said you could ever do. Anyhow they did, and they went broke.[18]

The Primary Producers’ Bank closed its doors in 1931 and was liquidated. By then the fraudster’s schemes were catching up with him. In December 1931 Musson was arrested along with three other men in Texas, Queensland, on a charge of conspiracy to commit fraud by enticing people to invest in the Tasmanian Credits Ltd.[19] The men were convicted, but on appeal their convictions were quashed.[20] There was no escape in 1933, however, when Musson was one of three men arrested in Queensland on charges of conspiracy for selling land to which they had no title in relation to the Texas Tobacco Plantation Pty Ltd of Queensland.[21] The men played on their military bearing, calling themselves Captain Brough, Major Field and Major Musson, although Musson admitted that he had not held the substantive rank of major during World War I.[22] All three were convicted and imprisoned for three years.[23] Frank Britton believed that Musson’s deceit cost him [Frank] an education like the one that his brothers and sisters enjoyed in Launceston and, with it, the chance to become a lawyer or doctor.[24]

[1] Bernard Cronin, The timber wolves, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1920.

[2] Llewellyn Irby to his family from Smithton 27 October 1922 (copy held by the author).

[3] Surveyor-General to Minister for Lands 12 May 1921, ‘Exploration survey Salmon River Wellington’, file LSD344/1/1 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

[4] ‘Welcome Swamp: Royal Commission’s Report’, Examiner, 13 March 1924, p.8.

[5] Mark Britton to Jim Livingstone 11 February 1924, Journal pp.102–06.

[6] Mark Britton, Britton Timbers, to Llewellyn Irby, Conservator of Forests, 11 February 1924, Journal pp.107–10.

[7] Mark Britton, Britton Timbers, to Llewellyn Irby, Conservator of Forests, 19 February 1924, Journal pp.111–12.

[8] Mark Britton, Britton Brothers, to S Moore, Forestry Office, Smithton, 14 October 1925, Journal p126.

[9] Phil Britton, ‘Memories of Christmas Hills (Brittons Swamp): the Story of the Sawmilling Industry and Farming in the Circular Head District 1900–1980’, pp.25–26 (manuscript held by the Britton Family).

[10] Phil Britton, ‘Memories of Christmas Hills (Brittons Swamp)’, p.26.

[11] JJ Dooley, ‘Far north-west’, Advocate, 8 October 1924, p.6.

[12] Mark Britton, Britton Brothers, to the Conservator of Forests 30 March 1925, Journal p.123.

[13] Mark Britton, Britton Brothers, to Garrett, District Forest Officer14 December 1925, Journal pp.127–28.

[14] ‘Men and women’, Advocate, 19 December 1922, p.2.

[15] ‘Primary Producers’ Bank’, Advocate, 6 December 1923, p.2.

[16] ‘Marrawah’, Advocate, 25 February 1924, p.4.

[17] Lorna Haygarth (née Britton) notes 1984.

[18] Frank Britton memoir 16 December 1992 (QVMAG).

[19] ‘Tasmanian Credits’, Advocate, 14 December 1931, p.8.

[20] ‘Tasmanian Credits’, Mercury, 31 May 1933, p.7.

[21] ‘Land in Queensland’, Mercury, 8 March 1933, p.8.

[22] ‘Tobacco Land’, Brisbane Courier, 11 March 1933, p.15.

[23] ‘Land fraud’, Canberra Times, 15 March 1933, p.1.

[24] Frank Britton memoir 16 December 1992 (QVMAG).