by Nic Haygarth | 06/10/24 | Tasmanian high country history

The collection of farms known as Narrawa in north-western Tasmania produced some tough old buggers. The small community west of Wilmot was home to the Carters, Vernhams, Williamses, Bramichs, Lehmans and others, bush farmers resigned to grubbing out, burning and stump jacking their way to cleared pasture. Crops like potatoes were planted in the ashes of the burnt trees as the beginning of farming operations.

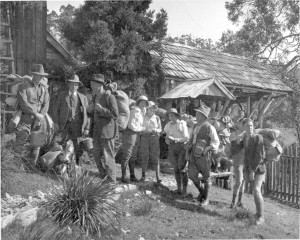

Jack (aka Johnny) Carter, Bill ‘Yorky’ Smith and Jack ‘Boy’ Griffiths clearing land at Narrawa. Griffiths, standing precariously on the log stack, was later killed in a similar operation on the Williams farm. Courtesy of Peter Carter.

After the harvest came the hunt. This was a chance to earn enough money to keep self and family for the rest of the year. Each hunter had his own territory somewhere in the north-western highlands.

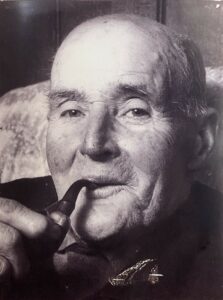

Harry ‘Poke’ Vernham/Vernon/Varnham (c1885–c1954)[1]

By the age of 20 Narrawa farmer Charles Henry Vernham already knew his way around Cradle Mountain, being conscripted in the search for hunter Bert Hanson who had gone missing near there in a winter fog.

[2] Harry excited more legends than probably any other bushman in his neck of the woods. He was a small man who, paradoxically, wore sandshoes (sneakers) in the bush. Harry was ‘square as a brick’ but so tough ‘you could drive nails into him and you wouldn’t hurt him’.

[3] Two stories bear out his toughness. In the snaring season of 1906 Harry cut his knee with an axe in the snow at Henrietta south of Wynyard. He covered the wound with salt and bandaged it with a green wallaby skin, telling his hunting partner ‘You’ll have to do all the snaring. I’ll peg out the skins and do all the cooking’.

[4] Eventually Harry presented himself to a doctor, who told him that he was just in time to prevent the onset of gangrene.

[5] Harry was then admitted to the Devon Cottage Hospital at Latrobe.

[6] Hearing of her son’s accident, Harry’s mother walked about 30 km from Wilmot to Latrobe to prevent a surgeon amputating his leg. She succeeded, but Harry was left with a stiff leg for the rest of his life.

[7]

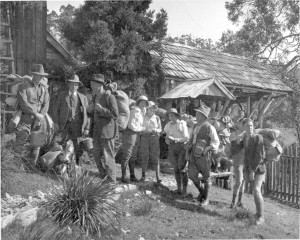

A young Harry Vernham sitting second from right in the second Bert Hanson search party, Weekly Courier, 30 September 1905, p.20.

On another occasion Harry’s nose was virtually detached from his face in a motorcycle accident.

[8] A doctor told him, ‘I’d better give you a whiff of something before I stitch it back on’. Harry is said to have replied, ‘I didn’t have a whiff when it come off so I don’t need one putting it back on’.

[9]

Hunting exploits

In 1914 Harry married Annie Eliza Carter, from the neighbouring family.

[10] They had a boy and three girls over the next four years, but Harry’s nickname Poke suggests that his sex life didn’t end there. At least the hunting seasons were celibate. Harry and his brother George Matthew ‘Native’ Vernham (1889–1966)

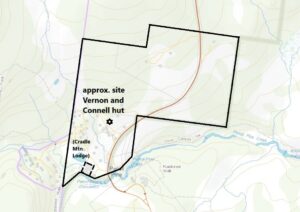

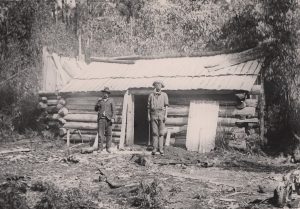

[11] had a hut on the south-eastern side of Mount Kate and a little log hut near the site of the present-day Cradle Mountain Lodge, the latter being pretty schmick as it was a lock-up affair.

[12] Other Harry Vernham hunting companions included Ernest ‘Son’ Bramich (1914) and Harry Leach (1933).

[13] Ted Murfet recalled camping with Harry in later years at Middlesex Station, the Twin Creeks Sawmill huts, the hut at Learys Corner, Daisy Dell and Robertson’s on the track into the Vale of Belvoir.

[14] They took a dozen balls of hemp for a season and used an old eggbeater to make up their treadle snares on a board about 1.2 m long. Usually they’d need 1000 snares for the season. In their worst season the pair shared £300 and in their best the take was £700—£350 each.

[15] By this time Harry had moved beyond the medicinal qualities of a green wallaby skin, developing new home remedies. He treated an ulcer on his leg with a plaster of onion wrapped up in a sock as a bandage and addressed a cold with swigs of Worcestershire sauce.

[16]

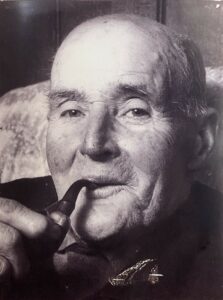

Harry Vernham (right) hunting much later in life. Courtesy of David Ball.

TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST© STATE OF TASMANIA

The slow farm development ritual undertaken at Narrawa also applied to the Connell family when they took up the Dunlavin property at the top of Chinamans Hill, Lower Wilmot, in the 1890s. While his older brother Lionel Connell (1884–1960) became a miner, Gordon stayed on the farm.

[18] He married Alice Jacklin in 1911, and the couple had at least four children during the next decade.

[19] In 1915/16 Lionel Connell and Dick Nichols built a hunting hut in the Little Valley, south of Lake Rodway, and in 1917, when Lionel took a 3-month sabbatical from the Shepherd and Murphy Mine to go hunting, his younger brother Gordon joined him at Cradle.

[20] Known as Bull because of his huge shoulders and great physical strength, Gordon hunted with Lionel as far south as the plains between Barn Bluff and the Fury River. He also worked over the so-called Todds Country at the head of the Campbell River.

[21] Gordon had a big kangaroo dog called Slocum which would take him to his kills. One day Gordon put his feet up and smoked for 30 minutes before Slocum returned. ‘Where is he then?’, the master prompted, setting the dog off towards Lake Carruthers to a big kangaroo he’d killed. But Slocum wasn’t finished, refusing to budge. ‘Well where is he then?’. Off they went again beyond Lake Carruthers to another big kangaroo carcass.

[22]

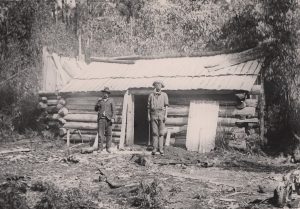

Gordon Connell, courtesy of Malcolm Dick.

Gordon hunted with Harry Vernham at Cradle in 1925 and 1926 and in other years around Middlesex and the Vale of Belvoir.

[23] They developed a regime of line camps or temporary shelters to get around their extensive snare lines, arriving at base camp only every three days. Gordon recalled icicles forming on Harry’s formidable body hair as he lugged his bag of skins about the snare lines. When Harry stripped off his shirt a huge cloud of steam arose from his singlet, an unusual form of enveloping fog. Wild bulls remaining from Field brothers’ Middlesex grazing operation were an occasional problem for hunters. The worst of these was a territorial bull called Bob because of the ‘bob’ in his tail. Another bull they put a bullet in roared back to life as they approached its apparent corpse. Gordon had a way of cutting a cartridge with a knife to concentrate its potency, but on this occasion it seems to have had the opposite effect.

[24]

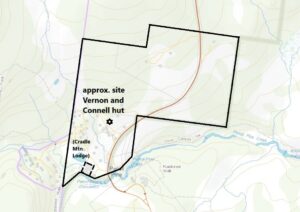

The Vernham and Connell 99-acre block at Pencil Pine Creek. TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST© STATE OF TASMANIA

How the area looked in 1949, showing the position of the hunting hut. Crop from aerial photo 0196_483, 15 April 1949.

In the 1930s Poke and Bull selected and started to pay off a 99-acre-block at Pencil Pine Creek enclosing the log hut and the old FH Haines sawmill site—land now partly occupied by Cradle Mountain Lodge, the Cradle Mountain shop and rangers’ quarters. Presumably they were either safeguarding their hold on valuable hunting territory or foresaw future tourism development. The pair failed to pay it off, and Lionel and Margaret Connell took over the payments. Lionel’s family were still using the log hut in 1940. Like most hunting huts in the area it had a skin shed chimney, that is, a very large timber chimney in which skins were pegged to dry close to the fire.

[25]

The tiger stories

Peter Carter, Harry Vernham’s nephew, claimed that Harry caught thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) in ‘hell-necker’ or ‘hellfire necker’ snares positioned at each end of a hollow log that contained a live wallaby. The ‘hellfire’ appears to have been a heavy-duty neck snare—not terribly surprising, as plenty of tigers were strangled in neck snares. What is surprising is Peter’s claim that his uncle sold skun tigers, that is, tiger carcasses, for £5. Perhaps he meant that he sold tiger skins for £5.

[26] Harry Vernham’s name was never entered on the list of payees for the £1 per head government thylacine bounty, although it is possible he claimed bounties through an intermediary. Still, the question needs to be asked why he went to so much trouble to strangle a tiger in a neck snare, when he could just have easily snared it alive by the paw in a foot or treadle device which would have earned him much more money. The story would only make sense if Harry had learned the whereabouts of a tiger or family of tigers and set up the hollow log trap as above, making sure the wallaby was restrained so that it couldn’t spring the snares while making its escape. Prices paid for tigers, dead or alive, varied wildly, so it’s hard to put even an approximate year on Vernham’s tiger sales.

[27]

Gordon Connell is another name missing from the government tiger bounty register. He once caught a thylacine dead in the snare—presumably a necker snare which strangled it—but he encountered others in the wild. Bull was said to have found a thylacine lair in one of three rock shelters down in the Fury Gorge while hunting nearby. He shouldn’t have been surprised then when, hunting the button-grass plains above it out of season, he heard an animal yelp. A big kangaroo hopped up the slope, as if disturbed, convincing Gordon and his mate that the police were below them. Then a tiger came up the slope in pursuit of the kangaroo. At regular intervals it stopped and gave three sharp yelps before continuing the chase, as did a second tiger behind it.

[28]

What a pity neither Poke nor Bull put pen to paper! We know so little about hunters’ experiences with tigers, but at least these anecdotes give glimpses of what they passed down through family and the hunting community.

[1] Years of birth and death are from Ancestry.com.au, no birth certificate or will was found.

[2] ‘Lost in the snow: a second search party’,

North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 July 1905, p.3.

[3] Peter Carter, interviewed by David Bannear, 16 July 1990, in

What’s the land for?: people’s experiences of Tasmania’s Central Plateau region, Central Plateau Oral History Project, Hobart, 1991, vol.3, p.4.

[4] Warren Connell, interviewed 8 September 1997; David Ball, interviewed 25 April 2020.

[5] Warren Connell.

[6] ‘Latrobe’,

North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 29 August 1906, p.2.

[7] Len Fisher,

Wilmot: those were the days, pp.46–47

[8] ‘Ulverstone’,

Advocate, 26 March 1934, p.6.

[9] David Ball, 24 April 2020. Ted Murfet also told this story to Len Fisher in

Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Devonport, 1990, p.82.

[10] Married 15 October 1914, marriage record no.801/1914, registered at Wilmot (TA).

[11] Born to Blackwood Hill, West Tamar labourer William Varnam [sic] and Christina Bowers on 1 February 1889, birth record no.736/1889, registered at Beaconsfield, RGD33/1/68 (TA),

https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=varnham, accessed 3 October 2023; died 7 February 1966, Will no.47656, AD960/1/105 (TA),

https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=vernham, accessed 3 October 2023.

[12] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 12 July 1914 (Pencil Pine Creek), 23 July 1914 (east side Mount Kate), NS234/27/1/4 (TA); 10 July and 10 August 1925 (Pencil Pine Creek) (QVMAG). Es Connell, interviewed by Nic Haygarth on 23 September 1997, confirmed the location of this hut.

[13] Gustav Weindorfer, in his diary, 16 and 18 June 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TA), recorded Harry Vernham and Bramich hunting Cradle Valley and Hounslow Heath with dogs. For Leach see ‘Taking game in close season alleged’,

Advocate, 12 September 1933, p.2.

[14] Ted Murfet, interviewed 15 October 1995.

[15] Ted Murfet, interviewed 15 October 1995.

[16] Ted Murfet, in Len Fisher,

Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Devonport, 1990, p.81.

[17] Born 29 April 1889 to Michael Connell and Frances Sayer, birth registration no.2639/1889, registered at Port Frederick, RGD33/1/68 (TA),

https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=gordon&qu=murray&qu=connell#, accessed 18 August 2024. The family was living at Torquay (East Devonport).

[18] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.10;

Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office Directory, 1919, p.277.

[19] Married 28 March 1911, file no.1384/1911, registered at Gunns Plains (TA).

[20] Gustav Weindorfer diary 29 December 1915 (Lionel Connell and Dick Nichols arrive at Cradle from Moina), NS234/27/1/5 (TA); 1–26 April 1917, NS234/27/1/7 (TA). Weindorfer possibly also referred to Gordon Connell in diary entries in May and June 1917, NS234/27/1/7 (TA).

[21] Todds Country was a name given by snarers to territory hunted by Bill Todd (1855–1926).

[22] Warren Connell.

[23] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 14 July 1925 and 23 March 1926 (QVMAG).

[24] Warren Connell.

[25] RE Smith diary, 29 June 1940, NS234/16/1/40 (TA).

[26] Peter Carter, p.10.

[27] For example,in James 1928 Harrison sold a tiger carcass to Colin MacKenzie in Melbourne for £12 (Harrison’s notebook). In 1930 Wilf Batty sold the carcass of the tiger he killed at Mawbanna for £5 (Wilf Batty; quoted in ‘The $55,000 search to find a Tasmanian tiger’,

Australian Women’s Weekly, 24 September 1980, p.41).

[28] Warren Connell.

by Nic Haygarth | 18/04/20 | Tasmanian high country history

When 52-year-old Maria Francis died of heart disease at Middlesex Station in 1883, Jack Francis lost not only his partner and mother to his child but his scribe.[1] For years his more literate half had been penning his letters. Delivering her corpse to Chudleigh for inquest and burial was probably a task beyond any grieving husband, and the job fell to Constable Billy Roden, who endured the gruesome homeward journey with the body tied to a pack horse.[2]

Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

By then Jack seems to have been considering retirement. He had bought two bush blocks totalling 80 acres west of Mole Creek, and through the early 1890s appears to have alternated between one of these properties and Middlesex, probably developing a farm in collaboration with son George Francis on the 49-acre block in limestone country at Circular Ponds.[3]

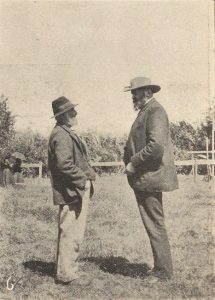

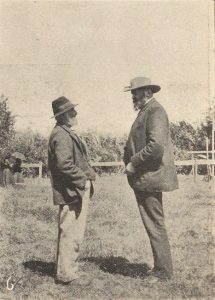

Jack Francis and second partner Mary Ann Francis (Sarah Wilcox), probably at their home at Circular Ponds (Mayberry) in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of Shirley Powley.

Here Jack took up with the twice-married Mary Ann (real name Sarah) Wilcox (1841–1915), who had eight adult children of her own.[4] Shockingly, as the passing photographer Frank Styant Browne discovered in 1899, Mary Ann’s riding style emulated that of her predecessor Maria Francis (see ‘Jack the Shepherd or Barometer Boy: Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis’). However, Mary Ann was decidedly cagey about her masculine riding gait, dismounting to deny Styant Browne the opportunity to commit it to posterity with one of his ‘vicious little hand cameras’.[5]

Perhaps Mary Ann didn’t fancy the high country lifestyle, because when Richard Field offered Jack the overseer’s job at Gads Hill in about 1901 he took the gig alone.[6] This encore performance from the highland stockman continued until he grew feeble within a few years of his death in 1912.[7]

Mary Ann seems to have been missing when the old man died. Son George Francis and Mary Ann’s married daughter Christina Holmes thanked the sympathisers—and Christina, not George or Mary Ann, received the Circular Ponds property in Jack’s will.[8] Perhaps Jack had already given George the proceeds of the other, 31-acre block at Mole Creek.[9]

Field stockmen Dick Brown (left) and George Francis (right) renovating the hut at the Lea River (Black Bluff) Gold Mine for WM Black in 1905. Ronald Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

By the time Mary Ann Wilcox died in Launceston three years later, George Francis had long abandoned the farming life for the high country. He was at Middlesex in 1905 when he renovated a hut and took part in the search for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain.[10] Working out of Middlesex station, he combined stock-riding for JT Field with hunting and prospecting.

Like fellow hunters Paddy Hartnett and Frank Brown, Francis lost a small fortune when the declaration of World War One in July 1914 closed access to the European fur market, rendering his winter’s work officially worthless. At the time he had 4 cwt of ‘kangaroo and wallaby’ (Bennett’s wallaby and pademelon) and 60 ‘opossum’ (brush possum?). By the prices obtaining just before the closure they would have been worth hundreds of pounds.[11] Sheffield Police confiscated the season’s hauls from hunters, who could not legally possess unsold skins out of season.

The full list of skins confiscated by Sheffield Police on 1 August 1914 gives a snapshot of the hunting industry in the Kentish back country. Some famous names are missing from the list. Experienced high country snarer William Aylett junior was now Waratah-based and may have been snaring elsewhere.[12] Bert Nichols was splitting palings at Middlesex by 1914 but may not have yet started snaring there.[13] Paddy Hartnett concentrated his efforts in the Upper Mersey, probably never snaring the Middlesex/Cradle region. His double failure at the start of the war—losing his income from nearly a ton of skins, and being rejected for military service—drove him to drink.[14]

‘Return of skins on hand on the 1st day of August [1914] and in my possession’, Sheffield Police Station.

| Name |

Location |

Kangaroo/wallaby |

Wallaby |

Possum |

| George Francis |

Msex Station |

448 lbs |

|

60 skins |

| Frank Brown |

Msex Station |

562 skins+ 560 lbs |

|

108 skins |

| DW Thomas |

Lorinna |

960 lbs |

|

310 skins |

| William McCoy |

Claude Road |

600 lbs |

|

66 skins |

| Charles McCoy |

Claude Road |

40 lbs |

|

|

| Geo [sic] Weindorfer |

Cradle Valley |

31 skins |

|

4 skins |

| Percy Lucas |

Wilmot |

408 skins |

|

56 skins |

| G Coles |

Storekeeper, Wilmot |

|

5 skins |

|

| Jack Linnane |

Wilmot |

|

15 skins |

|

| WM Black |

Black Bluff |

50 skins |

|

3 skins |

| James Perry |

Lower Wilmot |

|

2 skins |

13 skins |

Most of those deprived of skins were bush farmers or farm labourers who hunted as a secondary (primary?) income, while George Coles was probably a middleman between hunter and skin buyer:

Frank Brown (1862–1923). Son of ex-convict Field stockman John Brown, he was one of four brothers who followed in their father’s footsteps (the others were Humphrey Brown c1855–1925, John Thomas [Jacky] Brown, 1857–c1910 and Richard [Dick] Brown). He appears to have been resident stockman at Field brothers’ Gads Hill Station in 1892.[15] Frank and Louisa Brown were resident at JT Field’s Middlesex Station c1905–17. He died when based at Richard Field’s Gads Hill run in 1923, aged 59, while inspecting or setting snares on Bald Hill.[16]

David William Thomas (c1886–1932) of Railton bought an 88-acre farm on the main road at Lorinna from Harry Forward in 1912.[17] His 1914 skins tally suggests that farming was not his main source of income—so the loss must have been devastating. Other Lorinna hunters like Harold Tuson were working in the Wallace River Gorge between the Du Cane Range and the Ossa range of the mountains.

William Ernest (Cloggy) McCoy (1879–1968), brother of Charles Arthur McCoy below, was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Sheffield.[18] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy and the uncle of the well-known snarer Tommy McCoy (1899–1952).[19]

Charles Arthur (Tibbly) McCoy (1870–1962) was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Barrington.[20] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy. Charles McCoy caught a tiger at Middlesex, depositing its skins at the Sheffield Police Office on 30 December 1901.[21] He was the uncle of the later well-known snarer Tommy McCoy.

Gustav Weindorfer (1874–1932), tourism operator at Waldheim, Cradle Valley, during the years 1912 to 1932. By his own accounts during 1914 he shot 30 ‘kangaroos’, eight wombats, six ringtails and one brush possum, as well as taking one ‘kangaroo’ in a necker snare.[22] While the closure of the skins market would have handicapped this struggling businessman, these skins would have been useful domestically, and the wombat and wallaby meat would have gone in the stew.

Percy Theodore Lucas (c1886–1965) was a Wilmot labourer in 1914, which probably means that he worked on a farm.[23] Nothing is known about his hunting activities.

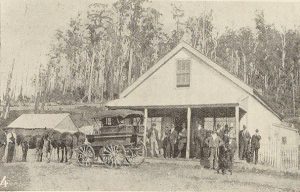

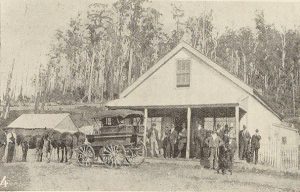

TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store, Percy Lodge photo from the Weekly Courier, 22 April 1905, p.19.

George Coles (1855–1931) was the Wilmot storekeeper whose sons, including George James Coles (1885–1977), started the chain of Coles stores in Collingwood, Victoria.[24] George Coles bought TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store in 1912, operating it until after World War One. In 1921 the store was totally destroyed by fire, although a general store has continued to operate on the same site up to the present.[25] The five skins in George Coles’ possession had probably been traded by a hunter for stores. Coles probably sold them to a visiting skin buyer when the opportunity arose.[26]

John Augustus (Jack) Linnane (1873–1949) was born at Ulverstone but arrived in the Wilmot district in 1893 at the age of nineteen, becoming a farmer there.[27] Like George Francis, Linnane joined the search party for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain in 1905, suggesting that he knew the country well.[28] His abandoned hunting camp near the base of Mount Kate was still visible in 1908.[29] Enough remained to show that Linnane was one of the first to adopt the skin shed chimney for drying skins.[30] He also engaged in rabbit trapping.[31] In 1914 he was listed on the electoral roll as a Wilmot labourer, but exactly where he was hunting at that time is unknown.[32]

Kate Weindorfer, Ronald Smith and WM Black on top of Cradle Mountain, 4 January 1910. Gustav Weindorfer photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Walter Malcolm (WM) Black (1864–1923) was a gold miner and hunter at the Lea River/Black Bluff Gold Mine in the years 1905–15. The son of Victorian grazier Archibald Black, WM Black was a ‘remittance man’, that is, he was paid to stay away from his family under the terms an out-of-court payment of £7124 from his father’s will.[33] He joined the First Remounts (Australian Imperial Force) in October 1915 by falsifying his age in order to qualify.[34] See my earlier blog ‘The rain on the plain falls mainly outside the gauge, or how a black sheep brought meteorology to Middlesex’.[35]

James Perry (1871–1948), brother of a well-known Middlesex area hunter, Tom Perry (1869–1928), who was active in the high country by about 1905. Whether James Perry’s few skins were taken around Wilmot or further afield is unknown.

No tigers at Middlesex/Cradle Mountain?

George Francis survived the financial setback of 1914. Gustav Weindorfer in his diaries alluded to collaboration with him on prospecting and mining activities, but they hunted in different areas. In 1919 Francis co-authored the three-part paper ‘Wild life in Tasmania’ with Weindorfer, which documented their extensive knowledge of native animals, principally gained by hunting them. At the time, the authors claimed, they were the only permanent inhabitants of the Middlesex-Cradle Mountain area, boasting nine years (Weindorfer) and 50 years’ (Francis) residency. They also made the interesting claim that the ‘stupid’ wombat survived as well as it did in this area because it had no natural predators, since the thylacine did not then and probably never had frequented ‘the open bush land of these higher elevations’.[36] While this suggests that George Francis had never encountered a thylacine around Middlesex, it’s hard to believe that his father Jack Francis didn’t, especially given the story that Jack’s early foray into the Vale of Belvoir as a shepherd for William Kimberley was tiger-riddled.[37] It’s also a pity the authors didn’t consult the likes of Middlesex tiger slayers Charlie McCoy (see above) and James Mapps—or rig up a séance with the late George Augustus Robinson and James ‘Philosopher’ Smith.

The dog of GA Robinson, the so-called ‘conciliator’ of the Tasmanian Aborigines, killed a mother thylacine on the Middlesex Plains in 1830.[38] Decades later, ‘Philosopher’ Smith the mineral prospector came to regard Tiger Plain, on the northern edge of the Lea River, as the most tiger-infested place he visited during his expeditions. It was popular among the carnivores, he thought, because the Middlesex stockman’s dogs by driving game in that direction provided a ready food source. ‘I thought it necessary’, he wrote about his experience with tigers,

‘to be on my guard against them by keeping a fire as much as I could and having at hand a weapon with which to defend myself in the event of being attacked by one or more of them … ‘[39]

Smith killed a female tiger on Tiger Plain and took its four pups from her pouch but found they could not digest prospector food (presumably damper, potatoes, bully beef, wallaby or wombat).[40] Philosopher’s son Ron Smith had no reason to doubt his father, as he found a thylacine skull on his property at Cradle Valley in 1913 which is now lodged in Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery.[41] There were still tigers in the Middlesex region at the cusp of the twentieth century. Like ‘Tibbly’ McCoy, James Mapps claimed a government thylacine bounty at this time, probably while working as a tributor at the Glynn Gold Mine at the top of the Five Mile Rise near Middlesex.[42]

George Francis in his will described himself as a ‘shepherd of Middlesex Plains’, yet he met his maker in the Campbell Town Hospital. His parents were dead and he had no remaining relatives. The sole beneficiary of his will was Golconda farmer and road contractor William Thomas Knight (1862–1938), probably an old hunting mate.[43] Francis’s job at Middlesex was filled by the so-called ‘mystery man’ Dave Courtney (see my blog ‘Eskimos and polar bears: Dave Courtney comes in from the cold’), whose life, as it turns out, is an open book compared to that of his elusive predecessor.

[1] Died 11 October 1883, death record no.167/1883, registered at Deloraine, RGD35/1/52 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=maria&qu=francis#, accessed 15 February 2020; inquest dated 13 October 1883, SC195/1/63/8739 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-63-8739, accessed 15 February 2020. A pre-inquest newspaper reporter incorrectly attributed her death to suicide by strychnine poisoning (editorial, Launceston Examiner, 23 October 1883, p.1).

[2] It is likely that Jack Francis and Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley conveyed Maria Francis’s body to Gads Hill Station, where Roden took delivery of it. See ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4; and ‘Supposed case of poisoning at Chudleigh’, Launceston Examiner, 13 October 1883, p.2. Later Roden had the job of removing Stanley’s body for an inquest at Chudleigh (Dan Griffin, ‘Deloraine’, Tasmanian Mail, 13 August 1898, p.26).

[3][3] For the land grant, see Deeds of land grants, Lot 5654RD1/1/069–71In 1890, 1892 and 1894 John and George Francis were both listed as farmers at Mole Creek (Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1890–91, p.200; 1892–93, p.288; 1894–95, p.260). Jack Francis was reported to have left Middlesex in March 1885, being replaced by Jacky Brown (James Rowe to James Norton Smith, 10 March 1885; and to RA Murray, 24 September 1885, VDL22/1/13 [TAHO]). However, he appears to have returned periodically.

[4] She was born to splitter John Wilcox and Rosetta Graves at Longford on 17 July 1841, birth record no.3183/1847 (sic), registered at Longford, RGD32/1/3 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=sarah&qu=wilcox, accessed 14 March 2020; died 25 October 1915 at Launceston (‘Deaths’, Examiner, 8 November 1915, p.1). Mary Ann’s youngest child, Eva Grace Lowe, was born in 1879.

[5] Frank Styant Browne, Voyages in a caravan: the illustrated logs of Frank Styant Browne (ed. Paul AC Richards, Barbara Valentine and Peter Richardson), Launceston Library, Brobok and Friends of the Library, 2002, p.84.

[6] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory for the period 1901–08 listed Jack Francis as an overseer at Gads Hill or Liena, while Mary, as she was described, was listed as a farmer at Liena, meaning Circular Ponds (1901, p.322; 1902, p.341; 1904, p.204; 1906, p.189; 1907, p.192; 1908, p.197).

[7] ‘A veteran drover’.

[8] ‘Return thanks’, Examiner, 2 March 1912, p.1; purchase grant, vol.36, folio 116, application no.3454 RP, 1 July 1912.

[9] Jack Francis bought purchase grant vol.18, folio 113, Lot 5654, on 25 November 1872. He divided it in half, selling the two lots on 6 May 1902 to Arthur Joseph How and Andrew Ambrose How for £30 each.

[10] ‘The mountain mystery: search for Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[11] 1 August 1914, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] See ‘William Aylett: career bushman’ in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.42–43.

[13] See ‘Bert Nichols: hunter and overland track pioneer’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.114.

[14] See ‘Paddy Hartnett: bushman and highland guide’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.93.

[15] On 20 April 1892 (p.179) Frank Brown reported stolen a horse which was kept at Gads Hill, Deloraine Police felony reports, POL126/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Well-known stockrider’s death’, Advocate, 4 June 1923, p.2.

[17] ‘Lorinna’, North West Post, 28 August 1912, p.2; ‘Obituary: Mr DW Thomas, Railton’, Advocate, 21 April 1932, p.2.

[18] Born 21 March 1879, birth record no.2069, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/57 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=william&qu=ernest&qu=mccoy. Accessed 10 April 2020.

[19] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[20] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[21] 30 December 1901, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Gustav Weindorfer diaries, 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TAHO).

[23] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.27.

[24] ‘About people’, Age, 22 December 1931, p.8.

[25] ‘Fire at Sheffield [sic]’, Mercury, 8 November 1921, p.5.

[26] Coles held a tanner’s licence in 1914 (‘Tanners’ licences’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 1 May 1914, p.109), but the legal requirement was that skins had to be sold to a registered skin buyer. Despite this, plenty of people tanned and sold their own skins privately.

[27] ‘”Back to Wilmot” celebration’, Advocate, 12 April 1948, p.2.

[28] 10 July 1905, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[29] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[30] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[31] On 18 April 1910, Linnane reported the theft of 200 rabbit skins from his hut valued at £2, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[32] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.26.

[33] ‘Supreme Court’, Age, 27 February 1885, p.6.

[34] World War One service record, https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1791278/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[35] Nic Haygarth website, http://nichaygarth.com/index.php/tag/walter-malcom-black/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[36] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Victorian Naturalist, vol.36, March 1920, p.158.

[37] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ’In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.2.

[38] George Augustus Robinson, Friendly mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (ed. Brian Plomley), Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1966; 22 August 1830, p.159.

[39] James Smith to James Fenton, 14 November 1890, no.450, NS234/ 2/1/15 (TAHO).

[40] ‘JS (Forth)’ (James Smith), ‘Tasmanian tigers’, Launceston Examiner, 22 November 1862, p.2.

[41] Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 26 September 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO); email from Tammy Gordon, QVMAG, 2019.

[42] Bounty no.242, 30 August 1898, LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO); ‘Court of Mines’, Launceston Examiner, 22 September 1897, p.3; 30 September 1897, p.3.

[43] Will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis, accessed 15 March 2020; ‘Funeral of Mr WF [sic] Knight’, Examiner, 15 April 1938, p.15.

by Nic Haygarth | 18/04/20 | Tasmanian high country history

When it comes to mythology, James ‘Philosopher’ Smith (1827–97), discoverer of the phenomenal tin deposits of Mount Bischoff in north-western Tasmania, has copped the lot. He was a mad hatter who ripped off the real discoverer, didn’t know tin when he saw it, threw away a fortune in shares (didn’t collect a single Mount Bischoff Co dividend) and ended up having to be saved from himself with a government pension.[1] Some of this hot air is still in circulation today—hopefully giving no one Legionnaire’s disease.

James ‘Philosopher’ Smith, wife Mary Jane and children Annie (left) and Leslie (right) at their near the Forth Bridge, 1877 or 1878. Peter Laurie Reid photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Unbeknownst to Fields’ Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis, he has also been mired in Smythology. My favourite version of how Jack Francis rescued—or might have rescued, given the chance—Philosopher Smith during his Mount Bischoff expedition is this published poem by E Slater:

‘How Mount Bischoff was found’

Philosopher Smith was full of go,

He tried lots of times to get through the snow,

With his swag on his back he was not very slow,

And he crawled through the bush when his tucker was low.

So he had to turn back, to Jack Francis he came,

To the stockriders’ hut on Middlesex Plains,

I was in the hut when the old man came in,

And gave him some whisky, I think it saved him.

He told us quite plain that the tin it was there,

So he never gave in, or did not despair,

He got some more tucker and went out again,

This time he found Bischoff (it was teeming with rain).[2]

Not content with having Francis save a teetotaller with a bottle of whisky, this bold author decided to mooch in on the tall tale and make himself the saviour. The poem continues, inexplicably, to describe Smith’s triumphant return from Bischoff to the Middlesex Hut after finding the tin and his exit right via Gads Hill and Chudleigh.

Why would Smith take that circuitous route home? At the time, he owned the property Westwood at Forth, but he was also renting land at Penguin while he was involved in opening up the Penguin Silver Mine.[3] At least one author has claimed that Smith’s definitive prospecting expedition was mounted from Penguin up the Pine Road he had had cut in 1868 to enable piners to exploit the forests at Pencil Pine Creek near Cradle Mountain.[4]

However, in his notes Smith made it clear that he travelled from Forth via Castra, the logical route from Westwood to the gold-bearing streams of the Black Bluff Range and the mineralised country around the Middlesex Plains. His main plan was to test the headwaters of the Arthur River for a gold matrix, in support of which he had had a stash of supplies packed out to the base of the Black Bluff Range.

And so, according to Tasmania’s late-nineteenth-century Book of Genesis, James Smith unearthed hope and prosperity in the form of tin at Mount Bischoff on 4 December 1871. What Smith’s notes tell us is that, after a week of work at Mount Bischoff, he ran out of food and—with apologies to those who have claimed he ate his dog[5]—retreated to the hut of Field’s Surrey Hills stockman-hunter Charlie Drury to beg a feed. Drury, not Francis, was the stockman Smith recalled meeting during his Mount Bischoff expedition.[6]

Action from the

Slaughteryard Gully Face of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mine, c1876, showing the yarding and slaughter of stock reflected in its name. Courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Regardless of Jack Francis’s non-glorification in the discovery of Bischoff, the tin mine brought a benefit to the denizens of Middlesex Station. The advent of the town of Mount Bischoff (Waratah), from about 1873, brought them closer to civilisation. However, there was no Mount Bischoff Tramway until 1877, and in its early days the town had no resident doctor. This meant that when a kick from a horse broke Jack Francis’s thigh at Middlesex in 1875, the nearest medical help was the unqualified ‘Dr’ Edward Brooke Evans (EBE) Walker of Westbank, Leven River (West Ulverstone). The round trip from the coast to Middlesex Station via the VDL Co Track—about 240 km—must have taken several days each way. ‘I had a nice jaunt to Middlesex’, Walker reported,

‘JT Field wrote asking me to go there to see a poor fellow a stock rider who had broken his thigh eight weeks before offering me £10!! to go there … I had to break it as it was 4 inches [9 cm] too short … I wrote and told him [JT Field] that he ought to supplement his offer but have had no answer … ‘[7]

Despite the pain, Jack—and/or his wife Maria Francis—made good use of this ‘down’ time, assembling a 30-shilling possum skin rug. ‘The rivers are not always fordable otherwise you would have the rugs more certain’, Jack told a customer, Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) local agent James Norton Smith.[8] He could ride, but for years the thigh injury still prevented him from walking far. In 1881 he asked the VDL Co to give him free passage to Waratah on the company’s horse-drawn tramway, enabling him to ride there after hitching his horse at the Surrey Hills stop.[9]

The establishment of Waratah also raised the Francis family’s social profile. One-time recipients of Her Majesty’s pleasure (they were both ex-convicts) became vice-regal hosts. In January 1878 Jack, Maria and possibly young George Francis put up Lieutenant Governor Frederick Weld at Middlesex Station. Escorted by a young Deloraine Superintendent of Police, Dan Griffin, and guided by Thomas Field, the vice-regal party negotiated Gads Hill on its way to visit the new mining capital—Weld being the first governor since George Arthur to tackle the VDL Co Track.[10] So it was that Jack Francis scored his moment of glory without even tempting the temperate Philosopher.

[1] For Smith finding the Mount Bischoff tin in the hut of stockman Charles Drury (‘Dicey’), see ‘The story of Bischoff’, Advocate, 24 April 1923, p.4. For Smith failing to identify the tin when he saw it, see, for example, Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science (ed. A Morton), vol.iv, Hobart, 1892, p.342. For Smith squandering a fortune and having to be saved by the Tasmanian Parliament see, for example, ‘Parliamentary notes’, Launceston Examiner, 21 October 1878, p.2. For Smith ‘not making a cent’ out of Mount Bischoff tin and not collecting a single dividend from the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, see, for example, Carol Bacon, ‘Mount Bischoff’; in (ed. Alison Alexander), The companion to Tasmanian history, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 2005, p.243.

[2] E Slater, ‘How Mount Bischoff was found’, Waratah Whispers, no.15, March 1982; reprinted there from ‘an old newspaper cutting’.

[3] Application to register the Penguin Silver Mines Company was gazetted on 23 August 1870. The assessment roll for the district of Port Sorell for 1870 lists Smith as the occupant of a hut on 47 acres at Penguin owned by Thomas Giblin of Hobart (Hobart Town Gazette, 22 February 1870, p.298).

[4] See ‘Penguin old and new: record of great development’, Weekly Courier, 17 December 1927, p.35.

[5] See, for example, ‘Nomad’, ’Correspondence: Philosopher Smith’, Circular Head Chronicle, 25 May 1927, p.3.

[6] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (TAHO).

[7] EBE Walker to James Smith, 8 July 1875, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[8] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 13 October 1875, VDL22/1/5 (TAHO).

[9] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO).

[10] ‘Vice-regal’, Tribune, 28 January 1878, p.2; ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

by Nic Haygarth | 06/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

DYI dentistry would make for intriguing reality TV (Channel Seven’s new blockbuster The chair anyone?) but in the nineteenth-century Tasmanian backwoods it was an everyday reality. Many people were far removed from medical services, and if you owned forceps you were licensed to operate. Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis (c1828–1912) was a model of self-sufficiency—hunter, stock rider, tanner, bootmaker, rug maker, leather worker, blacksmith, tool maker and dentist. Whether he aspired to more advanced surgery is unknown, but his prowess with the pincers must have made for some tense moments around the family dinner table.

From Chudleigh to Waratah, including the Field brothers’ stations of Middlesex Plains and Gads Hill. Map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Given that 40,000 years of Aboriginal custodianship are unrepresented on official charts of the area, it shouldn’t be surprising that Francis’s comparatively miniscule 40-year familiarity with this former Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) highland run is not recorded on its landmarks. Unlike his notable successor, Dave Courtney (recalled by Courtney Hill), the short, stocky Francis cut no memorable figure. He had no moustaches he could tie behind his back or thick beard to hide his face. Nor was he a ‘man of mystery’, as much as some might have preferred him to be. Francis’s convictism was unpalatable in some quarters even after his death. One newspaper editor omitted the words ‘though a prisoner for some trifling offence’ from his obituary.[1] Highland journalist Dan Griffin was less mealy-mouthed but confused Jack Francis the stockman with Jack Francis the builder and failed assassin.[2] Both men were transported from England to Van Diemen’s Land, the latter for taking pot shots at Queen Victoria, but Jack Francis the stockman was the most benign and pathetic of transportees, being a boy convicted of stealing a barometer.[3] These beginnings make his nickname ‘Jack the Shepherd’, recalling the notorious Irish outlaw, even more ironic.[4]

Jack Francis and Dan Griffin at the Chudleigh Races, from the Weekly Courier, 23 January 1904, p.23.

A native of County Armagh, Northern Ireland, Francis was apparently apprenticed as a ‘rough shoemaker’ when he faced court in Lancaster, Lancashire, England.[5] He probably had no idea how those skills would serve him in future years. Measuring all of 167 cm, he must have had a basic education. He could write, but with apparent difficulty, clearly preferring to dictate letters rather than write them himself.[6] Transported for seven years on the Egyptian in 1838, the boy convict served Launceston bootmaker Amos Langmaid before being assigned to rural masters James Grant at Tullochgorum near Fingal and Theodore Bartley at Kerry Lodge near Breadalbane.[7]

By now Francis was getting his leather in the field as well as at the end of an awl. After securing a certificate of freedom in 1845, he was a shepherd at Bentley near Chudleigh before securing his first posting to the highlands.[8] If childhood transportation to the antipodes hadn’t shaken his being to the core, his life now got a mite more adventurous. Because of Legislative Council parsimony, there were few public road bridges in northern Tasmania before 1865, but the VDL Co Track by which the highlands grazing runs were accessed from Chudleigh had dangerous fords much later than that. Negotiating the track for the first time, Francis and his two companions found the Mersey River almost impassable. Jim Garrett took the other two men’s clothes across on horseback, but with such difficulty that he could not return for the men, who of course had no chance of wading the torrent. They therefore had to spend the night without warm clothes or bedding, and were without food until late the next day when crossing became possible.[9]

This was probably in 1851 when grazier William Kimberley became the first victim of a beautiful mirage called the Vale of Belvoir. In that year Kimberley leased 1000 acres of this snowy glacial valley as a summer sheep run, posting Francis as their protector.[10] Barometer boy apparently had more of an issue with ‘wolves’ than with the highland weather. Thylacines—but more likely wild dogs—were said to have decimated Kimberley’s flock, although the survivors thrived, some being too fat to travel.[11]

Perhaps tubby sheep were Francis’s passport to the overseer’s position at Fields’ Middlesex Plains Station. This was a lonely, isolated job, with only the annual muster party and the occasional prospector like James ‘Philosopher’ Smith or surveyor like Charles Gould to interrupt proceedings. However, a routine of maintaining fences, preventing liver fluke in sheep, rescuing stock from bogs and patch-burning the runs left plenty of time for the hunter-stockman’s real occupation, snaring and hunting—primarily for the fur industry, secondarily for meat.

Middlesex Station, 1905, photo by RE Smith, courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Same view of Middlesex Station in 1993, 88 years on. Nic Haygarth photo.

The stock-in-trade of the highland stockman was the brush-possum-skin rug. The cold highland climate necessitated thick furs, and Francis, with his expertise in leatherworking, was well placed to take advantage of the demand for this specifically Tasmanian product.[12] Possum-skin carriage rugs and stock-whips he sold to VDL Co agent James Norton Smith fetched £2 and 16 shillings each respectively.[13] This was useful money, given that a stockman or shepherd’s annual wage was in the range of only £20–£30, supplemented by rations (flour, sugar, tea, tobacco, perhaps potatoes and some meat) delivered to a depot on Ration Tree Creek at the foot of Gads Hill, the milk he could wring from a cow, a few skilling sheep and an abundance of wallaby and wombat meat. He would have grown a few hardy vegetables, guarding them against frost and snow.

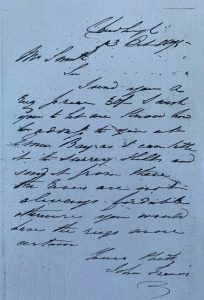

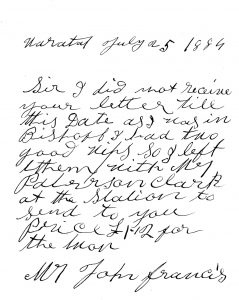

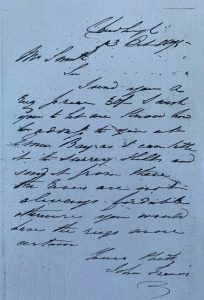

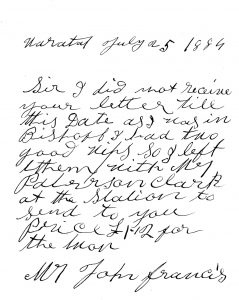

Jack Francis letters to the VDL Co’s James Norton Smith in 1875 and 1884 respectively, showing the difference between Maria’s fluent hand (above) and Jack’s laboured one (below).

From VDL22/1/9 and VDL22/1/12 (TAHO) respectively.

Not every woman would have fancied the lifestyle, but plenty of Jack’s contemporaries were accustomed to hardship. Jack Francis married 29-year-old house maid and factory worker Maria Bagwell (c1830–83) at Deloraine in 1860, subordinating his Roman Catholicism to her Protestantism.[14] She had been transported for seven years for stealing barley meal in Somerset in 1849. Perhaps she needed the nourishment, measuring only 166 cm as a nineteen-year-old. Her prison record is littered with the phrase ‘existing sentence of hard labour extended’. In 1852 she had been ‘delivered of’—deprived of?—an ‘illegitimate child’ at the Female House of Correction.[15] What happened to this unnamed girl from an unnamed father? Just as elusive is George Francis (?–1924), the child apparently born to Jack and Maria Francis during their time at Middlesex.[16]

The house maid seems to have taken to station life. In 1865 Maria Francis escorted surveyors James Calder and James Dooley from Middlesex Station to Chudleigh. To their ‘amazement’, their guide sat astride her horse like a man

‘and thus rode the whole way … with an amount of unconcern that surprised us not a little; and as if determined that we should not lose sight of this extraordinary feat of horsewomanship, she rode in front of us almost the whole distance, smoking a dirty little black pipe from one end of the journey to the other’.[17]

The couple’s son George Francis had arrived by 1871, when a child was mentioned by a visitor to Middlesex. Now Jack Francis revealed himself to be not just a skilled shoemaker and possum-skin rug maker but an expert tanner, clothing himself and his family in leather. They lived

‘in a clean and comfortable hut. A very few minutes sufficed for Mrs Francis to give us a cup of good tea, with abundance of milk, toast, and bread and butter, and when bedtime came she provided us with flealess bed-clothes, an unusual luxury in the bush….’

Jack Francis was ‘a very handy fellow … adept at shoeing a horse or drawing a tooth, having himself made a first-rate pair of forceps with which to perform this last-named operation …’ [18]

Final resting place for Jack and Maria Francis, Old Chudleigh Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

Headstone of Maria Francis, Old Chudleigh Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

Today not even a headstone in the Old Chudleigh Cemetery records this go-getter’s existence. Around Middlesex Station the ‘old’ European names are forgotten: Misery (now Courtney Hill), the Sirdar (after Horatio Herbert Kitchener of the South African War), Pilot, Sutelmans Park, Vinegar Hill, Twin Creeks. Who named them all and why? No journalist interviewed the old station hands. Yet while the Francises left their mark only in written history, digitisation of archival records is enriching our knowledge of displaced people like them, who lived remarkable lives in remote places.

[1] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[2] ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

[3] See conduct record for John Francis, transported on the Egyptian for seven years in 1839, CON31/1/12, image 175 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-12$init=CON31-1-12p175, accessed 16 February 2020.

[4] For the nickname see, for example, ‘River Don’, Weekly Examiner, 4 October 1873, p.11; ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[5] Francis’s obituarist in, for example, ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4, claimed that he was born at Woodburn, Buckinghamshire, 5 February 1828. Francis’s convict records make him a native of County Armagh.

[6] Indent for John Francis, CON14/1/48, images 25 and 26 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/tas/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fARCHIVES_DIGITISED$002f0$002fARCHIVES_DIG_DIX:CON14-1-48/one, accessed 16 February 2020. Compare, for example, his letter to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO), written by his wife Maria Francis, with his letter to James Norton Smith, 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO), written in his own hand after Maria’s death.

[7] Conduct record, as above.

[8] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[9] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[10] ‘Crown lands’, Courier, 5 February 1851, p.2; ‘Surveyor-General’s Office’, Courier, 3 December 1851, p.2; ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[11] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[12] HW Wheelright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[13] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 10 October 1873, NS22/1/4; and 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO).

[14] Married 24 December 1860, marriage record no.657/1860, at St Mark’s (Anglican) Church, Deloraine, RGD37/1/19 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages&qf=NI_NAME_FACET%09Name%09Francis%2C+John%09Francis%2C+John, accessed 15 February 2020. On his marriage certificate, Jack underestimated his age as 28 years.

[15] See conduct record for Maria Bagwell, transported on the St Vincent, CON41/1/25, image 16 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON41-1-25$init=CON41-1-25p16, accessed 15 February 2020. See also birth record for Maria Bagwell’s unnamed illegitimate female child, born 7 September 1852, birth record no.1780/1852, registered at Hobart, RGD33/1/4 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=NI_NAME%3D%22Bagwell,%20Maria%22#, accessed 15 February 2020.

[16] George Francis died 12 January 1924, will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages+%7C%7C+Deaths%09Deaths+%7C%7C+Wills%09Wills&qf=PUBDATE%09Year%091906-1976%091906-1976, accessed 16 February 2020.

[17] James Erskine Calder, ‘Notes of a journey’, Tasmanian Times, 18 May 1867, p.4.

[18] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

by Nic Haygarth | 12/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian nature tourism history

William Dubrelle Weston, aka ‘Peregrinator’. Photo from the Launceston Family Album, courtesy of the Friends of the Launceston LINC.

Ernest Milton Law, Weston’s hiking and legal partner. Photo from the Launceston Family Album, courtesy of the Friends of the Launceston LINC.

In March 1886 the pastoralist Alfred Archer of Palmerston, south of Cressy, guided two Launceston schoolboys across the Central Plateau through poorly charted country to Lake St Clair.[1] This was the first in a series of extraordinary highland excursions for sixteen-year-old William Dubrelle Weston (1869–1948) and fifteen-year-old Ernest Milton Law (1870–1909). Later adventures would include probably the first bushwalk to the Walls of Jerusalem, visits to Great Lake and Mount Barrow, and the first two tourist trips to Cradle Mountain—‘the summit of our ambition’.[2]

On most of these expeditions they would be joined by two chums they knew from the Launceston Grammar School, the brothers Richard Ernest Smith (1864–1942), known as Ernest or ‘Old Crate’, and Alfred Valentine ‘Moody’ Smith (1869–1950). Weston’s letters from the period show the friends’ high-spirited camaraderie, and how hiking relieved the stresses of study, career, faith, self-discipline and social life during the transition from adolescence to manhood. Bushwalking was already popular in Tasmania, with accounts of highland excursions appearing regularly in newspapers.

Cradle Mountain and Dove Lake, as Peregrinator’s party would have seen them, without tourist infrastructure. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Why did they choose Cradle Mountain in 1888? The peak received few visitors. No ascents are recorded between James Sprent’s trigonometrical survey in about 1854 and that by Dan Griffin and John McKenna in March 1882.[3] The discovery of gold on the Five Mile Rise on the western side of the Forth River gorge had increased traffic towards Cradle on the old Van Diemen’s Land Company Track, but the peak itself remained more remote from Launceston than even Lake St Clair was.

However, the Launceston Grammar old boys were now confident, independent bushwalkers. The Smith brothers were in charge of the commissariat. Alf was the hunter of the party, armed with a rifle. Currawongs and green parrots were landed on the way to Cradle Mountain, although a snake despatched by two weapons was left off the menu. Porridge, bread and butter, johnny cakes and beef fed the party at other times. Water proved so scarce that on the Five Mile Rise (near today’s Mail Tree or Post Office Tree on the Cradle Mountain Road) it was squeezed out of moss, a decoction that not even the addition of the emergency brandy and whisky could make palatable.

The party attempted to reach Cradle not by today’s tourist route across the Middlesex Plains, then south to Pencil Pine Creek, but by the direct route which took them into the deep, scrubby Dove River and Campbell River gorges. This was the hunters’ route to Cradle, but Weston’s party soon lost their way. With supplies dwindling on their fifth day out, there was nothing for it but to turn for home. Weston, who had taken to writing under the pseudonym of ‘Peregrinator’ or ‘Mr Peregrinator’, had been tantalised by Cradle’s ethereal heights:

‘Before us rose the imposing mass of the mountain; to our right was another stupendous gorge; and high above it and us a splendid eagle sailed in clam serenity, above all the ups and downs of terrestrial life and toil.’[4]

Ernest Smith wrote of the same vista months late: ‘I have that scene as vividly before me now while I am writing as if I were there, and I shall have until I die’.[5] There was no question but that they would return.

Two summers passed before ‘the old Company’ could reassemble, and they did it without ‘Moody’ Smith. ‘At last Mr Peregrinator and two friends got loose from their respective occupations’, Weston opened his second Cradle Mountain narrative. Infrastructure had improved in the three years since their last Cradle adventure. The Mole Creek branch railway, a new Mersey River bridge and the Forth River cage (flying fox) expedited travel. For a second time Fields’ Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley doubled as their official weighbridge. That this time their packs averaged about 49 lbs (22 kg) each, compared to 43.5 lbs (20 kg) on the previous trip, suggests heavier provisioning in an effort to secure their goal. Extra cocoa, ship’s biscuit, porridge, rice and tea probably came in handy—as did bushranger Martin Cash’s autobiography—when time lost to rain extended the trip to thirteen days.

The four chose the easier route via Middlesex Station, which proved a useful staging-post, and provided a stockman to guide them onwards. Like other early Cradle climbers, Peregrinator’s party mistook the more obvious north-eastern end of the mountain for the summit. They then had to dodge the series of intervening spires to reach the true summit at the south-western end, where they found the timber remains of James Sprent’s trigonometrical station.[6] Standing on Cradle’s pinnacle—the ‘summit of our ambitions’—in perfect stillness, with the island spread out below him, Weston struck a melancholic note:

‘We had been seeking grandeur of nature and now we beheld its plaintive softness … Sound, there was none. Yonder stood the frowning buttresses of the mountain … many a glistening silver line revealed a stream plunging in headlong fury down the distant slopes, and there asleep in the very arms of nature herself lay a tiny lakelet [probably Lake Wilks], whose breast was sacred e’en to the evening zephyr. How comes it that so much of this world’s intensest scenes of beauty are set in a minor key?’

Sadly, Weston recognised that the party’s hiking career ended then and there on the summit. Now aged from 20 to 26 years, the men would soon sacrifice their youth and their physical prime to adult responsibilities. Yet Weston’s usual picaresque banter, historical footnotes and topical commentary enlivened their extraordinary ‘final push’ home—about 45 km from Middlesex Station to Sheffield by foot in a day. Peregrinator’s romantic description of the jewels of the night guiding his descent from the Mount Claude saddle must have raised eyebrows among those who knew the place only for labour with pack-horse and bullock team on their way to the gold mines on the upper Forth River. After alighting from the train in Launceston, the trio made straight for the photographer’s studio and there immortalised ‘the old Co’s’ swansong. ‘The closing scene was enacted some days later when we called for our proofs’, Peregrinator concluded.

‘On our appearance we were some time making our photographer perceive that we were the same individuals, who had called in with the black billies and aspiring beared a few days before. And now the Cradle trip like many like it remains a please reminiscence of the past and a joy for the future.’[7]

William Dubrelle Weston (2nd from left) with guide Bert Nichols (3rd from left) before setting out from Waldheim to climb Cradle Mountain in 1933. Fred Smithies photo courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

It is unlikely that Alf ‘Moody’ Smith, who became a Church of England minister in New South Wales, ever stood on the summit of Cradle Mountain. Ernest Law never repeated the adventure, dying, tragically, of typhoid in 1909, aged only 38. Neither Ernest Smith nor Weston renounced hiking altogether, with the former leading boys on mountain treks in his career as a school-teacher. But only Weston returned to the top. In 1933, 45 years after he first tackled Cradle Mountain and now 64 years old, he noted in the Waldheim Chalet visitors’ book at Cradle Valley:

‘With thankfulness to God’s goodness it is recorded that WD Weston who led the first Launceston party (late Ernest M Law and Mr Richard Ernest Smith) in December 1890–January 1891 (ascent Jan 2nd 1891) reascended to the trig on the Cradle 28th December 1933’.[8]

Ironically, the urban conqueror of Lake St Clair, the Walls of Jerusalem and Cradle Mountain more than four decades earlier, was now led to the summit by Overland Track guide Bert Nichols, a bushman fifteen years his junior. It is fitting that such an early spruiker of highland tourism should return to walk part of the ‘new’ track that popularised the region.

[1] ‘The Tramp’ (WD Weston), ‘About Lake St Clair’, The Paidophone, vol.II, no.7, September 1987, pp.7–8; ‘Shanks’ Ponies’ (WD Weston), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Launceston Examiner, 22 December 1888, p.2.

[2] See Nic Haygarth, “’The summit of our ambition”: Cradle Mountain and the highland bushwalks of William Dubrelle Weston’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.56, no.3, December 2009, pp.207–24.

[3] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Cradle country’, Tasmanian Mail, 8 February 1897, p.4.

[4] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Notes of a trip in the vicinity of the Cradle Mountain’, Colonist, 17 March 1888, p.4.

[5] RE Smith to WD Weston, date illegible, CHS47, 2/55 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [henceforth QVMAG]).

[6] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain: no.3’, Launceston Examiner, 4 March 1891, supplement, p.2.

[7] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain: no.5’, Launceston Examiner, 11 March 1891, supplement, p.1.

[8] Waldheim Visitors’ Book, vol.2, p.8, 1991:MS0004 (QVMAG).