To the edge of the Walls: Stephen Spurling’s 1903 hike to the Little Fisher ‘Gulf’

It would be easy to dismiss hiking trips as frivolous. Urban people taking the airs. Weekenders marvelling at ‘new’ landscapes others work in all week. Spiritual awakenings in firestick farmlands. Bushwalkers are rarely explorers even in the European sense of discovering a place known to the Aborigines for 60,000 years. Generally they tread a well-trodden path.

But I do get interested when bushwalking accounts give us historical insights. They can tell us when something happened, when a structure was built or destroyed or a track cut. They can help trace the development of technology. Take, for example, the story of photographer Stephen Spurling III (1876–1962) lugging 12 x 10-inch glass plates up Stacks Bluff through snow drifts on home-made snow-shoes to take the first Tasmanian highland snow scenes.[1]

There is a charming naivety about all Spurling’s accounts of hiking the northern ranges in the years 1895–1913. These were young men plunging agreeably into what was to them the unknown. In his report of a 1908 trip from Ironstone Mountain to Lake St Clair Spurling described the Central Plateau as ‘A Terror Incognito’, his party being unable to score reliable information as to what lay ahead of them, just ‘rumours of precipitous valleys and impassable bogs dense belts of scrub and other obstacles to progress …’[2] Highland stockmen and hunters, or experienced Launceston hikers such as William Dubrelle (WD) Weston and Richard Ernest ‘Crate’ Smith could have advised him, had he known to ask them. There were no walking clubs then to act as a repository of hiking knowledge. There was no digital newspaper index to search. This was a world not over-stimulated by visual images. No internet, no TV, no neon billboards. You could buy albums of Tasmanian views from photographers like John Watt (JW) Beattie, but the era of press photography was just dawning.

Spurling could see a market for Tasmanian scenery in both albums and illustrated weekend newspapers. He loved the Central Plateau. In 1899 he and a group of friends climbed the Great Western Tiers at Caveside and crossed the Plateau to see Devils Gullet.[3] In early 1901 he was part of a group that ascended the Tiers above Meander and worked its way west past Lake Mackenzie, once again to Devils Gullet.[4] Spurling scenes of the Tasmanian highlands were a striking feature of the Weekly Courier from its inception in July 1901.

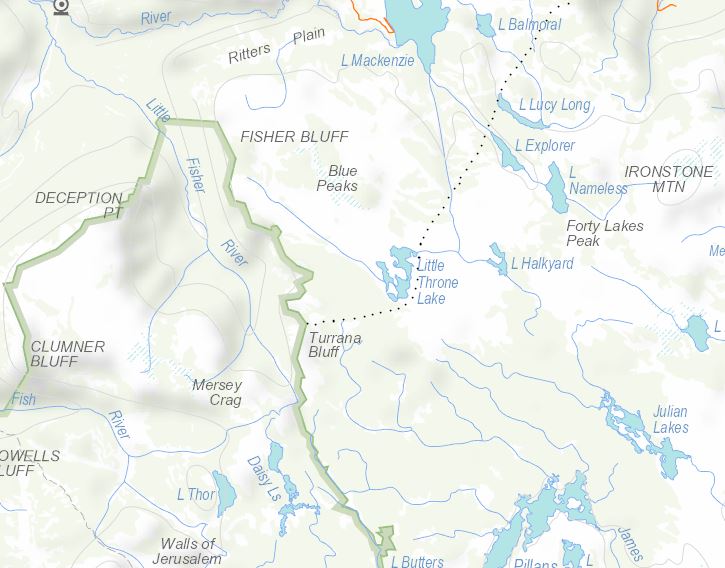

Devils Gullet was then known as ‘The Gulf’. However, Spurling had heard of a ‘magnificent’ ‘Second Gulf’ ten miles (sixteen kilometres) back from the escarpment where the Fish River—actually the Little Fisher River—made its escape to the Mersey. Spurling’s map placed this gulf, quite correctly, in the vicinity of the Walls of Jerusalem—something of a mythic land for bushwalkers well into the twentieth century. Although surveyor James Scott had charted the Walls of Jerusalem as early as 1849, and the mountain complex was well known to highland graziers and hunters, hikers were in the dark about it. Scott’s map was not in circulation, nor were the earlier exploratory accounts of John Beamont and Jorgen Jorgensen.[5] Launceston walkers WD Weston and probably Ernest Law had visited the Walls of Jerusalem and the so-called Rugged Mountains after Christmas in 1888, but the only copy of their account of the expedition disappeared in the Daily Telegraph newspaper office and was never published.[6]

Blissful in their ignorance, Spurling and his three mates set out for the Second Gulf one autumn weekend in 1903. This time they chose the Higgs Track up the Great Western Tiers near Western Creek. Although Spurling’s report of the trip was not his most entertaining, he observed familiar picaresque conventions of the time. A ‘Jehu’ (biblical chariot driver) delivered the party from Deloraine Railway Station to Dale Brook and back. Only one of the party, the ‘Infant’, received a nickname, that being punishment for describing photography as ‘funny business’.

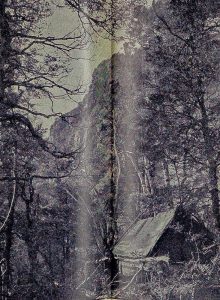

Campsite on the Higgs Track below the lip of the plateau. Stephen Spurling III photo from the Weekly Courier, 4 April 1903, pp.20-21.

Moist westerly winds impeded their progress up the valley of Dale Brook. The four made base camp in a canvas-roofed shelter just below the lip of the plateau, and spent the rest of the day battling the wind as they reconnoitred around Lake Balmoral. From a hill they sized up the ‘unknown’ country to the south-west that they hoped to penetrate.

One of the Blue Peaks and its accompanying lake, Stephen Spurling III photo, from the Weekly Courier, 4 April 1903, p.21.

Next day they made their push for the Second Gulf. Leaving Lake Balmoral to their right, they reached lake Lucy Long, forded Explorer Creek and the Fisher River, and by 9 am had attained the summit of one of the Blue Peaks. A tongue of land separating Little Throne Lake from its northern neighbour provided a bridge, and by 11.30 am, after six hours’ hard walking, the party stood near Turrana Bluff on the brink of ‘a tremendous gorge, known to a few hunters and shepherds as the Second Gulf, and which corresponds on the map with the Walls of Jerusalem’.

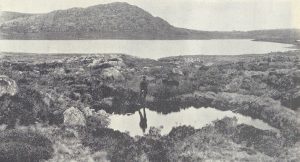

View of the ‘Second Gulf’ (Little Fisher River ‘Gulf’), Stephen Spurling III photo from the Weekly Courier, 4 April 1903, p.20.

Dazzled, perhaps, by his view of the Walls, Spurling described only the ‘wild, serrated form’ of the ‘Rugged Mount’, which made ‘a most impressive background’. Four long silvery streaks of waterfalls dropped over the chasm in the distance. Despite tramping from Ironstone Mountain to Lake St Clair in 1908, this is as close as he would ever get to the Walls of Jerusalem.

Mist cut short the day’s exploration. Yet, with practical ingenuity typical of the time, Spurling’s party cornered and killed a wallaby, part of which they roasted for their evening meal back at base camp. Their final day was spent revisiting Devils Gullet and exploring the course of the Fisher River above it without, apparently, finding the Parsons Hut which Spurling would photograph on his next expedition to these parts—the winter 1904 snow-shoe extravaganza.[7]

[1] Stephen Spurling, ‘Ben Lomond in winter’, Weekly Courier, 19 September 1903, pp.25–26; 26 September 1903, p.26; 3 October 1903, pp.25–26; 10 October 1903, p.35.

[2] S Spurling Junior (Stephen Spurling III), ‘Across the plateau’, unpublished account held by the Spurling family, Devonport. The account is dated February 1913, but the numbering of Spurling’s photos from this trip suggests 1908. The many typographical errors in the paper suggest that someone else transcribed it from Spurling’s handwritten original. The date may be another transcription error.

[3] ‘Union Jack’ (Stephen Spurling III), ‘A trip to the Gulf and Westmoreland [sic] Falls’, Examiner, 20 January 1900, p.7.

[4] ‘The Hermit’ (Stephen Spurling III), ‘In the highlands of Tasmania’, Weekly Courier, 20 July 1901, pp.123–24.

[5] For Beamont: ‘Copy of Mr Beamont’s journal taken on his tour to the Western Mountains, Van Diemen’s Land, Monday, 1st Decr, 1817’, Historical Records of Australia, series III, vol.III, Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, Canberra, 1921, pp.586–90. For Jorgensen: His travels were deciphered by Arch Meston and CJ Binks, see Binks, Explorers of western Tasmania, Mary Fisher Bookshop, Launceston, 1980, pp.48–57.

[6] Weston alludes to the Walls of Jerusalem trip twice in an account of a Cradle Mountain trip in 1890–91. See ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain’, Examiner, 4 March 1891, supplement, p.2 and 11 March 1891, supplement, p.1. Weston also appears to allude to this trip in a letter to AV Smith (2 May 1889, CHS47 2/56, QVMAG) and comments on its disappearance in a letter to RE ‘Crate’ Smith (24 September 1889, CHS47 2/55, QVMAG). For

[7] S Spurling jun, ‘On the Western Tiers: trip to the Fish River Gulf’, Tasmanian Mail, 4 April 1903, p.4. For the winter 1904 snow-shoe extravaganza, see Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, ‘Sandy Beach Lake Hut’, in Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.84–91.