by Nic Haygarth | 18/04/20 | Tasmanian high country history

When it comes to mythology, James ‘Philosopher’ Smith (1827–97), discoverer of the phenomenal tin deposits of Mount Bischoff in north-western Tasmania, has copped the lot. He was a mad hatter who ripped off the real discoverer, didn’t know tin when he saw it, threw away a fortune in shares (didn’t collect a single Mount Bischoff Co dividend) and ended up having to be saved from himself with a government pension.[1] Some of this hot air is still in circulation today—hopefully giving no one Legionnaire’s disease.

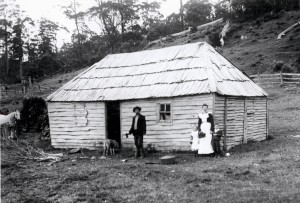

James ‘Philosopher’ Smith, wife Mary Jane and children Annie (left) and Leslie (right) at their near the Forth Bridge, 1877 or 1878. Peter Laurie Reid photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Unbeknownst to Fields’ Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis, he has also been mired in Smythology. My favourite version of how Jack Francis rescued—or might have rescued, given the chance—Philosopher Smith during his Mount Bischoff expedition is this published poem by E Slater:

‘How Mount Bischoff was found’

Philosopher Smith was full of go,

He tried lots of times to get through the snow,

With his swag on his back he was not very slow,

And he crawled through the bush when his tucker was low.

So he had to turn back, to Jack Francis he came,

To the stockriders’ hut on Middlesex Plains,

I was in the hut when the old man came in,

And gave him some whisky, I think it saved him.

He told us quite plain that the tin it was there,

So he never gave in, or did not despair,

He got some more tucker and went out again,

This time he found Bischoff (it was teeming with rain).[2]

Not content with having Francis save a teetotaller with a bottle of whisky, this bold author decided to mooch in on the tall tale and make himself the saviour. The poem continues, inexplicably, to describe Smith’s triumphant return from Bischoff to the Middlesex Hut after finding the tin and his exit right via Gads Hill and Chudleigh.

Why would Smith take that circuitous route home? At the time, he owned the property Westwood at Forth, but he was also renting land at Penguin while he was involved in opening up the Penguin Silver Mine.[3] At least one author has claimed that Smith’s definitive prospecting expedition was mounted from Penguin up the Pine Road he had had cut in 1868 to enable piners to exploit the forests at Pencil Pine Creek near Cradle Mountain.[4]

However, in his notes Smith made it clear that he travelled from Forth via Castra, the logical route from Westwood to the gold-bearing streams of the Black Bluff Range and the mineralised country around the Middlesex Plains. His main plan was to test the headwaters of the Arthur River for a gold matrix, in support of which he had had a stash of supplies packed out to the base of the Black Bluff Range.

And so, according to Tasmania’s late-nineteenth-century Book of Genesis, James Smith unearthed hope and prosperity in the form of tin at Mount Bischoff on 4 December 1871. What Smith’s notes tell us is that, after a week of work at Mount Bischoff, he ran out of food and—with apologies to those who have claimed he ate his dog[5]—retreated to the hut of Field’s Surrey Hills stockman-hunter Charlie Drury to beg a feed. Drury, not Francis, was the stockman Smith recalled meeting during his Mount Bischoff expedition.[6]

Action from the

Slaughteryard Gully Face of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mine, c1876, showing the yarding and slaughter of stock reflected in its name. Courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Regardless of Jack Francis’s non-glorification in the discovery of Bischoff, the tin mine brought a benefit to the denizens of Middlesex Station. The advent of the town of Mount Bischoff (Waratah), from about 1873, brought them closer to civilisation. However, there was no Mount Bischoff Tramway until 1877, and in its early days the town had no resident doctor. This meant that when a kick from a horse broke Jack Francis’s thigh at Middlesex in 1875, the nearest medical help was the unqualified ‘Dr’ Edward Brooke Evans (EBE) Walker of Westbank, Leven River (West Ulverstone). The round trip from the coast to Middlesex Station via the VDL Co Track—about 240 km—must have taken several days each way. ‘I had a nice jaunt to Middlesex’, Walker reported,

‘JT Field wrote asking me to go there to see a poor fellow a stock rider who had broken his thigh eight weeks before offering me £10!! to go there … I had to break it as it was 4 inches [9 cm] too short … I wrote and told him [JT Field] that he ought to supplement his offer but have had no answer … ‘[7]

Despite the pain, Jack—and/or his wife Maria Francis—made good use of this ‘down’ time, assembling a 30-shilling possum skin rug. ‘The rivers are not always fordable otherwise you would have the rugs more certain’, Jack told a customer, Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) local agent James Norton Smith.[8] He could ride, but for years the thigh injury still prevented him from walking far. In 1881 he asked the VDL Co to give him free passage to Waratah on the company’s horse-drawn tramway, enabling him to ride there after hitching his horse at the Surrey Hills stop.[9]

The establishment of Waratah also raised the Francis family’s social profile. One-time recipients of Her Majesty’s pleasure (they were both ex-convicts) became vice-regal hosts. In January 1878 Jack, Maria and possibly young George Francis put up Lieutenant Governor Frederick Weld at Middlesex Station. Escorted by a young Deloraine Superintendent of Police, Dan Griffin, and guided by Thomas Field, the vice-regal party negotiated Gads Hill on its way to visit the new mining capital—Weld being the first governor since George Arthur to tackle the VDL Co Track.[10] So it was that Jack Francis scored his moment of glory without even tempting the temperate Philosopher.

[1] For Smith finding the Mount Bischoff tin in the hut of stockman Charles Drury (‘Dicey’), see ‘The story of Bischoff’, Advocate, 24 April 1923, p.4. For Smith failing to identify the tin when he saw it, see, for example, Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science (ed. A Morton), vol.iv, Hobart, 1892, p.342. For Smith squandering a fortune and having to be saved by the Tasmanian Parliament see, for example, ‘Parliamentary notes’, Launceston Examiner, 21 October 1878, p.2. For Smith ‘not making a cent’ out of Mount Bischoff tin and not collecting a single dividend from the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, see, for example, Carol Bacon, ‘Mount Bischoff’; in (ed. Alison Alexander), The companion to Tasmanian history, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 2005, p.243.

[2] E Slater, ‘How Mount Bischoff was found’, Waratah Whispers, no.15, March 1982; reprinted there from ‘an old newspaper cutting’.

[3] Application to register the Penguin Silver Mines Company was gazetted on 23 August 1870. The assessment roll for the district of Port Sorell for 1870 lists Smith as the occupant of a hut on 47 acres at Penguin owned by Thomas Giblin of Hobart (Hobart Town Gazette, 22 February 1870, p.298).

[4] See ‘Penguin old and new: record of great development’, Weekly Courier, 17 December 1927, p.35.

[5] See, for example, ‘Nomad’, ’Correspondence: Philosopher Smith’, Circular Head Chronicle, 25 May 1927, p.3.

[6] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (TAHO).

[7] EBE Walker to James Smith, 8 July 1875, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[8] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 13 October 1875, VDL22/1/5 (TAHO).

[9] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO).

[10] ‘Vice-regal’, Tribune, 28 January 1878, p.2; ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

by Nic Haygarth | 11/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

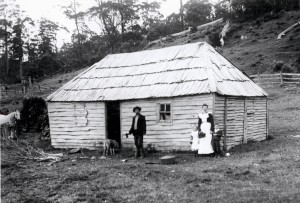

In Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, written with Simon Cubit, I told the story of a visit made to the Browns’ hut at Middlesex Station by the Anglican Bishop of Tasmania, Henry Hutchinson Montgomery and the Vicar of Sheffield, JS Roper, in February 1901.[1] Montgomery’s photo of the Brown family at their hut, featuring an eighteen-year-old Linda Brown with already two children, and the family turned out in Sunday best for the camera, tells us much about their isolated lifestyle, their social expectations and their pride.

Henry Montgomery’s photo of Field stockman Jacky Brown and his wife Linda Brown at their hut, with children Mollie (the babe in arms) and William (standing with his father). The girl standing beside Linda is possibly from the Aylett family and fulfilling the role of maid. PH30-1-3836 (TAHO).

The underlying story in this photo is the decline of the Field grazing empire, which was becoming as rickety as the Middlesex hut. That empire had been established by ex-convict William Field senior (1774–1837) and his four sons William (1816–90), Thomas (1817–81), John (1821–1900) and Charles (1826–57). The death of John Field of Calstock, near Deloraine, in the previous year had closed those generations which had spread half-wild cattle from the Norfolk Plains/Longford area as far as Waratah, intimidating other graziers and dominating its impoverished landlord, the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co). The Fields were notorious for occupation by default, and they knew that legitimately occupying the VDL Co properties of the Middlesex Plains and the Hampshire and Surrey Hills would also allow them to occupy all the open plains of the north-western highlands gratis. The Fields’ power over the VDL Co increased as the company’s fortunes declined. In 1840 the Field brothers leased the 10,000-acre Middlesex from the VDL Co for 14 years at £400 per annum.[2] In 1860, after financial losses forced the VDL Co to retreat to England as an absentee landlord, they obtained a lease of the Hampshire and Surrey Hills plus Middlesex—170,000 acres in all—for the same price, £400.[3] The problem for the VDL Co was that few other graziers wanted such a large, isolated holding, and that any who did dare to take it on would have to first remove the Fields’ wild cattle. In 1888 the Fields screwed the VDL Co down further to £350 for the lot for the first two years of a seven-year lease, raising the price to £400 for the final five years.[4]

Nor were any of these negotiations straightforward. With every lease there was a battle to collect the rent, necessitating letters between the respective solicitors, Ritchie and Parker for the VDL Co, and Douglas and Collins for the Fields. Thomas or John Field would stall, demanding a reduction in rent for fencing, rates or police tax. On one occasion they requested the right to seek minerals, and to make roads and tramways on the leased land—and to take timber for the construction of this infrastructure.[5] Worse yet, in 1871 some of Fields’ wild cattle from the Hampshire or Surrey Hills got confused with VDL Co stock and ended up on the Woolnorth property at Cape Grim, and the VDL Co couldn’t figure out how to get rid of them.[6] Since Fields would soon ask to rent Woolnorth—and be refused—it was as if their advance guard had infiltrated the property ahead of a storming of the battlements.[7] The VDL Co’s solicitor told them that to shoot the offending animals would be to risk a Field law suit, leaving the company no option but to buy them from Fields and then weed them out for slaughter.[8]

However, now things were changing. By the 1890s reduced meat prices and natural attrition had taken their toll on the Field empire. John Field was the only one of the four brothers still standing. The VDL Co was now fielding offers from potential buyers of the large Surrey Hills block, as the company looked to land sales and timber for financial redemption. John Field’s final gesture in 1900 was to offer the VDL Co £75 per year for Middlesex.[9] The VDL Co wanted £125, and in the new year of 1901 the executors of John Field’s estate haggled for a concession. They wanted their landlord to offset some of the increased rental by paying for improvements to the station. ‘The place is greatly out of repair and the house would require to be a new one throughout’, WL Field told VDL Co local agent James Norton Smith. ‘The outbuildings are none and there is not a fence on the place’.[10]

We can see for ourselves that some of this, at least, was true. The unfenced, out-of-repair Middlesex ‘house’ in Montgomery’s photo had already undergone renovations, a chimney having been removed from its eastern end. However, Field was probably exaggerating a little. Perhaps there were no outbuildings, but Fields probably always kept a second hut at Middlesex for the stockmen who came up for the muster.

Silence spoke for the VDL Co. Receiving no reply to his request, WL Field agreed to the annual rental of £125 for seven years, with an option of seven years more at £150 per annum, noting that ‘we have the 10,000 acres of govt land adjoining it at a rental of £60 and I consider the block as good as the co’s and it will save a lot of fencing having both …’.[11]

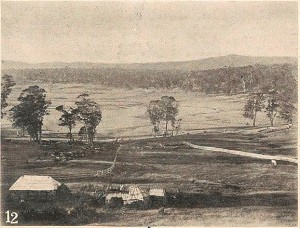

The Middlesex Station huts in February 1905, with Jacky, Linda Brown and two children standing in front of the second (mustering) hut. The hut occupied by the family can be seen at the extreme left in the left-hand photo, set well away from the others. The curl of smoke from the distant hut confirms the location of the chimney at its rear.

Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

A close-up of the Browns in front of the mustering hut. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

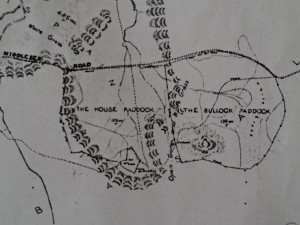

Perhaps the VDL Co did eventually submit to improvements. By 1905, when Jacky and Linda Brown were still in residence, there was a collection of buildings at Middlesex Station, including a ramshackle hut with a boarded-up window which was used by mustering stockmen and travellers. The main hut used by the Browns was set further east, away from these buildings, outside the House Paddock, which had now been fenced.

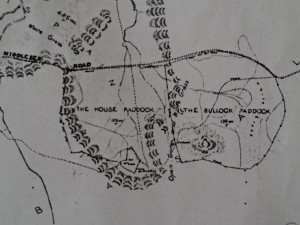

However, on the down side, the Fields were losing their unfettered reign over the highlands. A small land boom occurred in the upper Forth River country when a track was pushed through from the Moina region to Middlesex. The Davis brothers from Victoria tried to cultivate the Vale of Belvoir, and highland grazing runs were selected.[12] Frank and Louisa Brown were Fields’ Middlesex residents in November 1906 when Jack Geale, the new owner of the Weaning Paddock, asked new VDL Co agent AK McGaw to pay half the cost of fencing the eastern side of the Middlesex block, which would enable him to separate his herd from the Fields’.[13] McGaw sent surveyor GF Jakins with a team of men to Middlesex to re-mark the boundaries. The resulting survey shows the fenced paddock, the collection of buildings and the separate stockman’s hut.

A crop from GF Jakins’ 1908 survey of the Middlesex Plains block, showing the House and Bullock Paddocks and the collection of buildings at the head of the House Paddock. From VDL343-1-359, TAHO, courtesy of the VDL Co.

Jakins also marked Olivia Falls (‘falls 300 ft’, ‘falls 60 ft’)—better known today as Quaile Falls—just outside the south-east corner of the Middlesex block. This casts doubt on the story of Quaile Falls being discovered by Roy Quaile while searching for stock.[14] The falls were probably known to the miners who worked the Sirdar silver mine nearby in the Dove River gorge from 1899—and were possibly given their present name in recognition of Wilmot farmer Bob Quaile’s visits there with tourists.[15] And what did the Aborigines call this ‘second Niagara’ long before that?

Perhaps it was knowledge of the ‘red’ pine growing on the south-western corner of the Middlesex Plains block that prompted Ron Smith of Forth to enquire about buying the block from the VDL Co.[16] That land owner would have enjoyed this attention. In 1908 Fields signed up for their second seven-year lease on Middlesex, at the increased rental of £150 per year. They had to agree to allow the VDL Co to sell any part of the Middlesex Plains block during that term excepting the 640 acres around the ‘homestead’.[17] As a regular visitor to Middlesex Station on his way to and from Cradle Mountain, Smith had no illusions about the standard of accommodation provided there. In January 1908 he and his party stayed in a new hut that had been built for the mustering stockmen. ‘We were very glad to do so’, Smith noted, ‘as the old hut was very much out of repair … ‘ It was a two-room hut with a moveable partition, so that it could be converted into one room as needed.[18]

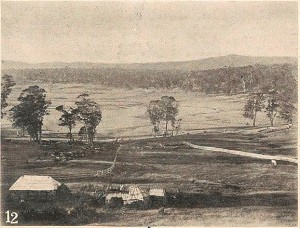

A collection of Middlesex buildings in December 1909 or January 1910. These seem to be the same buildings visible in the 1905 photo. The main hut further east is not shown here. Ron Smith photo from the Weekly Courier, 22 September 1910, p.17.

Louisa Brown with a pet wallaby, January 1910. This appears to be the same main hut photographed by Montgomery in 1901. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

By December 1910 that hut was also in a state of disrepair. The Fields asked the VDL Co to renew or extend the two-roomed hut in time for the muster in the following month: ‘Up to now they have lived in the old house, but it is really unsafe. Mr Sanderson [VDL Co accountant] has seen the house that was built by us about four years ago, as he was there and stayed in it just after it was built. There is a man living there [Frank Brown] who would split the timber & do it’.[19]

Main hut at Middlesex Station, Christmas 1920. The figure second from right appears to be Dave Courtney, with moustaches but as yet no beard.

Ray McClinton photo, LPIC27-1-2 (TAHO)

Such is the incomplete photographic record of Middlesex Station at the time that it is unknown whether the mustering hut was replaced. However, we can say more about the main hut used by the stockman. The hut shown in the 1901 and 1910 photos appears to have remained the stockman’s hut in 1920 when Ray McClinton snapped it, this time with Dave Courtney the resident stockman. The chimney had been rebuilt with a vertical arrangement of palings, and a skillion had been added at the back. A prominent stump standing beside the hut in this photo must have been just out of picture in Montgomery’s 1901 shot.

After Fields had rented Middlesex from the VDL Co for 82 years, in 1922 JT Field, son of the late John Field of Calstock, bought the block, ending the uncertainty about its future. However, the lone figure of 49-year-old stockman Dave Courtney was emblematic of the Fields’ dwindling presence in the highlands, and his long, flowing beard of the 1920s and 1930s would not have allayed the impression of a once vigorous enterprise slowly grinding to a halt.

[1] Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.24–29.

[2] Edward Curr, Outward Despatch no.215, 18 November 1840, VDL1/1/5 (TAHO).

[3] Inward Despatch no.291, 16 November 1857, VDL 1/1/6 (TAHO).

[4] Minutes of VDL Co Court of Directors, 16 February 1888, VDL201/1/10 (TAHO).

[5] Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 16 April 1875, VDL22/1/5 (TAHO).

[6] John Field offered to settle the matter by selling the wild cattle to the VDL Co for £100. See Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 7 July 1871. See also Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 14 October 1871 and 3 September 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[7] Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 16 February 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[8] Ritchie & Parker to James Norton Smith, 31 October 1871, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[9] Minutes of VDL Co Court of Directors 3 October 1900, VDL201/1/11 (TAHO).

[10] WL Field to James Norton Smith, 19 January 1901, VDL22/1/32 (TAHO).

[11] WL Field to James Norton Smith, 30 April 1901 and 15 June 1901, VDL22/1/32 (TAHO).

[12] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.18–23.

[13] JW Geale to EK McGaw, 26 November 1906, VDL22/1/38 (TAHO).

[14] Leonard C Fisher, Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Port Sorell, 1990, p.150.

[15] See, for example, ‘The Cradle Mountain’, Examiner, 5 January 1909, p.6.

[16] AK McGaw to Ron Smith, 23 January 1905, NS234/1/18 (TAHO). The term ‘red pine’ was often used indiscriminately to describe both the King Billy (Athrotaxis selaginoides) and pencil (Athrotaxis cupressoides) pine timber.

[17] WL Field to AK McGaw, 24 September 1908, VDL22/1/40 (TAHO).

[18] Ron Smith, ‘Trip to Cradle Mountain: RE Smith and the Adams Brothers, January 1908’, in Ron Smith, Cradle Mountain, with notes on wild life and climate by Gustav Weindorfer, the author, Launceston, 1937, pp.67–77.

[19] WT and JL Field, writing on behalf of WL Field, to AK McGaw, 7 December 1910, VDL22/1/42 (TAHO).