In the mid-1920s thylacines were still reported by bushmen in remote parts of the north-west. Luke Etchell claimed there was a time when he caught six or seven ‘native tigers’ per season at the Surrey Hills.[1] Like Brown brothers at Guildford, Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) hands at Woolnorth were still doing a trade in live native animals—although the latter property was out of tigers. On 7 July 1925 Hobart City Council paid the VDL Co £60 10 shillings for what can only be described as two loads of ‘animals’—presumably Tasmanian devils and quolls—recorded as being carted out to the nearest post office at Montagu during the previous month.[2] A further transaction of £30 was recorded in October 1925, when it is possible Woolnorth manager George Wainwright junior hand delivered a crate of live native animals to Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo.[3]

James ‘Tiger’ Harrison (1860–1943) of Wynyard took his animals dead or alive. He bought and sold living Tasmanian birds and marsupials, including tigers, but also hunted for furs in winter. In July 1926 Harrison and his Wynyard friend George Easton (1864–1951) secured government funding of £2 per week each to prospect south of the Arthur River for eight weeks.[4] However, their main game was hunting: the two-month season opened on 1 July 1926.

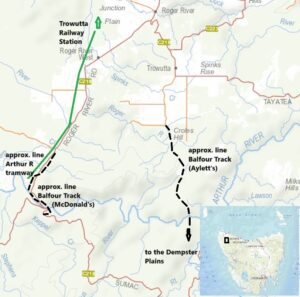

Easton, an experienced bushman in his own right, made snares most evenings until the pair departed Wynyard on 14 July.[5] At Trowutta Station they boarded the horse-drawn, wooden-railed tram to the Arthur River that jointly served Lee’s and McKay’s Sawmills.[6] Next day, Arthur Armstrong from Trowutta arrived with a pack-horse bearing their stores, and the pair set out along the northern bank of the Arthur towards the old government-built hut on Aylett’s track.[7] However, on a walk to the Dempster Plains to shoot some wallaby to feed their dogs, Harrison injured his knee so badly that he couldn’t carry a pack. So before they had even set some snares the pair was forced to return home.[8] On their slow, rain-soaked journey they sold their stores to the Arthur River Sawmill boarding-house keeper Hayes—the only problem being delivery of said stores from their position up river.[9] While Harrison went home by horse tram and car, Easton had to help Armstrong the packer retrieve the stores.[10]

‘Tiger country’ around the Arthur River

If not for the injury Harrison may have secured more than furs over the Arthur. One of the European pioneers in that area was grazier Fred Dempster (1863–1946), who appears to have rediscovered pastures celebrated by John Helder Wedge in 1828.[11] Out on his run in 1915 Dempster met a breakfast gatecrasher with cold steel. The elderly tiger reportedly measured 7 feet from nose to tail and being something of a gourmet registered 224 lbs on Dempster’s bathroom scales.[12] In dramatising this shooting, anonymous newspaper correspondent ‘Agricola’ mixed familiar thylacine attributes with the fanciful idea of its ferocity:

This part is the home of the true Tasmanian tiger … This animal must not be confounded with the smaller cat-headed species [he perhaps means the ‘tiger cat’, that is, spotted-tailed quoll, Dasyurus maculatus] so prevalent beyond Waratah, Henrietta and other places. The true species is absolutely fearless in man’s presence, and if he smells meat will follow the wayfarer on the lonely bush tracks for miles, stopping when he does and going on when he resumes his walk. It has been proved beyond question that these brutes will not shift off the paths when met by man, and they will always attack when cornered.[13]

One mainland newspaper was apparently so confused by ‘Agricola’s’ account that he called Dempster’s thylacine ‘a huge tiger cat’.[14]

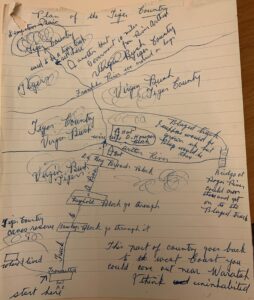

Trowutta people had no problem distinguishing quoll from tiger. They caught the latter unwittingly while snaring. Fred and Martha Crole and family of Trowutta made hundreds of snares on a sewing machine, eating the wallaby meat and selling the skins they caught. One of their boys, Arthur Crole (1895–1972), landed a tiger alive in a snare, killed it, tanned the hide and used it as a bedside rug.[15] While south of the Arthur, Harrison and Easton were unlucky not to run into Trowutta farmers Fred and Violet Purdy, who caught a tiger in a footer snare there during the 1926 season. When the Purdys approached the captured animal it broke the snare and disappeared. However, tigers also frequently visited their hut south of the river at night and they saw their footprints in the mud next morning.[16] Violet Purdy claimed to have spent six months straight living in the ‘wild bush’ (the hunting season in 1926 was only July and August), and her observations of the thylacine suggest someone with at least second-hand knowledge. Like ‘Agricola’, she knew of the tiger’s reputed habit of refusing to move off a track to let a human pass. Unlike him, she attested to the animal’s shyness. Purdy recommended ‘a couple of good cattle dogs’ as the means of tracking it down. She and her husband found thylacine tracks at the Frankland River as they crossed it to reach the Dempster Plains.[17] Decades later Purdy regaled the Animals’ and Birds’ Protection Board with her tales, illustrating them with a map of ‘tiger country’ between Trowutta and the Dempster Plains.

formerly Violet Purdy of Trowutta. From AA612/1/59 (TA).

Snaring at Woolnorth

By the time Easton got home to Wynyard, Harrison, apparently recovered from his knee injury, had arranged for them both to snare at Woolnorth, where no swags needed to be carried, since stores were supplied. The VDL Co employed hunters every season to kill ‘game’, this serving the dual purpose of saving the grass for the stock and bringing the company income at a time of low agricultural prices. At this time hunters paid a royalty of one in six skins to the company.

Easton’s diary entries give rare insight into a hunting engagement. Harrison and Easton took the train to Smithton and caught the mail truck to Montagu, from which they were borne by chaise cart to the Woolnorth homestead. That night the snarers were put in a cottage generally reserved for the VDL Co agent, AK McGaw.[18] Next day station manager George Wainwright junior showed them their lodgings (tents next to a lagoon which served as the water supply) and how snaring (using springer snares but also neck snares along fences) and skinning were done at Woolnorth. Wainwright, an old hand, claimed to be able to skin 30 animals per hour.[19] Storms, horse leeches, which had a way of attaching themselves to the human scalp, and cutting springers and pegs kept the snarers very well occupied between snare inspections, an 11-km-long daily routine. The game was nearly all wallaby and ringtails, and Harrison and Easton dried their skins not in a skin shed but by hanging them in trees.[20] Bathing meant a sponge bath with a prospecting dish full of cold water—which also constituted the laundry facilities.[21] The last day of the season at Woolnorth was traditionally an all-in animal shoot, after which the season’s skins were baled, treated with an arsenic solution to kill insects and delivered to a skins dealer.[22] In the two-month 1926 season the VDL Co made £493 from the fur industry, a big reduction on the previous year (£1296) when the season had lasted three months.[23]

However, Harrison didn’t last the distance, calling it quits on 13 August after barely two weeks, leaving Easton to carry on alone until the season ended eighteen days later. Their skin tally at 13 August stood at 16½ dozen—198 skins or 99 apiece.[24]

Returning to ‘tiger country’

Once again ‘Tiger’ Harrison was in the wrong place at the wrong time to live up to his nickname. While he was working at tiger-free Woolnorth, timber worker, hunter and sometime miner Alf Forward snared two tigers, one alive, one choked to death by a stiff spring in a necker snare at the Salmon River Sawmill south of Smithton.[25] Forward is said to have exhibited the living one in Smithton before selling it to Harrison.[26] He almost had another live one in the following month, when a tiger detained by Forward’s snare for two days bit his capturer’s hand, thereby effecting its escape.[27]

Harrison eventually decided to cut out the middle-man. From 1927 he conducted expeditions specifically to obtain living thylacines to sell. He had no luck until in June 1929 he caught one 3 km south-west of Takone.[28] The Arthur River catchment remained ‘tiger country’ in the mid-1930s when ‘Pax’ (Michael Finnerty) and Roy Marthick claimed to have seen them while prospecting.[29] The question of whether they are there today still entertains Tarkine tourists and the worldwide thylacine mafia.

[1] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (Tasmanian Archives, henceforth TA).

[2 Payment recorded 7 July 1925. On 9 June 1925: ‘W Simpson taken animals to Montagu’; 22 June 1925: ‘W Simpson went to Montagu with load of animals’, Woolnorth farm diary, VDL277/1/53 (TA).

[3] Payment recorded on 13 October 1925. On 4 October 1925 George Wainwright junior and his wife departed Woolnorth for the Launceston Agricultural Show (Woolnorth farm diary VDL277/1/53). It is possible that he took a crate of animals on the train to Hobart.

[4] GW Easton diary, 1 July 1926 (held by Libby Mercer, Hobart).

[5] GW Easton diary, 1–14 July 1926.

[6] GW Easton diary, 15 July 1926.

[7] GW Easton diary, 16 July 1926.

[8] GW Easton diary, 18 July 1926.

[9] GW Easton diary, 23 July 1926.

[10] GW Easton diary, 25 and 26 July 1926.

[11] JH Wedge, ‘Official report of journeys made by JH Wedge, Esq, Assistant Surveyor, in the North-West Portion of Van Diemen’s Land, in the early part of the year 1828’, reprinted in Venturing westward: accounts of pioneering exploration in northern and western Tasmania by Messrs Gould, Gunn, Hellyer, Frodsham, Counsel and Sprent [and Wedge], Government Printer, Hobart, 1987, p.38.

[12] See for example ‘Boat Harbour’, North West Post, 22 February 1915, p.2. Dempster probably didn’t have any bathroom scales with him. Rather mysteriously, the author of ‘A huge tiger cat’, Westralian Worker, 19 March 1915, p.6, put the animal’s weight as ‘2 cwt’ (224 lbs).

[13] ‘Agricola’, ‘Farm jottings’, North West Post, 24 February 1915, p.4. In another column ‘Agricola’ claimed with equal dubiousness that under Mount Pearse trappers caught tigers in pits, and that if more than one tiger was collected in the same pit at the same time the captured animals would fight to the death. See ‘Agricola’, ‘Farm jottings’, North West Post, 10 July 1914, p.4.

[14] ‘A huge tiger cat’, Westralian Worker, 19 March 1915, p.6.

[15] Fred and Graham Crole, in Women’s stories: different stories—different lives—different experiences: a Circular Head oral history project (compiled and edited by Pat Brown and Helene Williamson), Forest, Tas, 2009, p.192.

[16] The hut was on Aylett’s Track to Balfour.

[17] Violet Kenevan, Kingswood, New South Wales, to secretary of the Animals’ and Birds’ Protection Board, 30 October 1956, AA612/1/59 (TA).

[18 GW Easton diary, 27 July 1926.

[19] GW Easton diary, 30 July 1926.

[20] GW Easton diary, 18 August 1926.

[21] GW Easton diary, 15 August 1926.

[22] GW Easton diary, 31 August and 6–9 September 1926; Woolnorth farm diary, 31 August 1926, VDL277/1/54 (TA).

[23] The figures are from VDL129/1/7 (TA).

[24] GW Easton diary, 13 August 1926.

[25] ‘Hyena choked in snare at Salmon River’, Circular Head Chronicle, 11 August 1926, p.5.

[26] ‘TT, from New Town’, ‘Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 24 August 1954, p.4, claimed that Alf Forward caught the animal in a kangaroo snare at the Salmon River ‘less than 30 years ago’ and sold it to Harrison after putting it on show in Smithton.

[27] ‘Hand bitten by a hyena’, Circular Head Chronicle, 29 September 1926, p.5.

[28 GW Easton diary, 17 June 1929; Circular Head Chronicle, 29 May 1929.

[29] See ‘Pax’ (Michael Finnerty), ‘A “bush-whacker’s” experience in the north-west’, Mercury, 6 May 1937, p.8; Roy Marthick to the Fauna Board, 10 February 1937 (TA); Roy Marthick quoted by Charles Barrett, ‘Out in the open: nature study for the schools’, Weekly Times (Melbourne), 10 July 1937, p.44.