by Nic Haygarth | 22/01/17 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian landscape photography

Up one side … a Citröen-Kegresse on the Kensington Sandhills near Sydney. From the Weekly Courier, 27 September 1923, p.23.

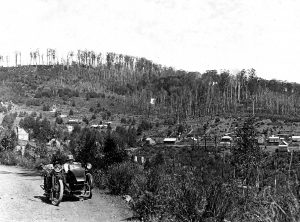

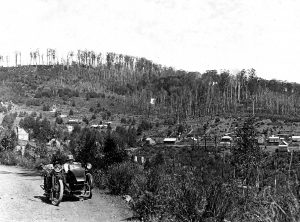

Down the other …. the Citröen-Kegresse prototype on its way to Waldheim, 1924. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Anton Lade.

They don’t make Citröens like that anymore. Gustav Weindorfer of Waldheim Chalet, the highland resort at Cradle Valley, beat the snow by shooting for meat on skis when he began living there in isolation in 1912.[1] At around the same time, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia understandably ordered a grander hunting vehicle for snow conditions—with caterpillar tracks for back wheels. Hannibal’s elephantine passage through the Alps to surprise the Romans had nothing on the Citröen-Kegresse, the assault vehicle which resulted from the meeting of French car manufacturer André Citröen and the Tsar’s resourceful mechanic, Adolph Kegresse, after the Russian Revolution.[2]

The Tsar’s caterpillar-tracked hunting technology now drove a prototype that breached the Himalayas en route to China and crossed the Sahara to Timbuktu. It also took a crack at Cradle. In 1924 Latrobe garage owner William Lade publicised his acquisition of a Citröen-Kegresse in Wynyard, Penguin, Latrobe and Devonport, being fined in the last town for demonstrating its ability to climb the steps of the Seaview Hotel.[3] There were fewer rules and few police in the highlands. Rearing over hills and plummeting down the other side, Lade’s vehicle roared up to Waldhiem with ten people aboard close to midnight on 12 April 1924.[4] Launceston’s Daily Telegraph newspaper had high expectations of the Citröen-Kegresse trip:

‘It had been expected that the machine would attempt the last 1½ miles [from Waldheim] to the [Cradle Mountain] summit, but as the rain continued to fall throughout the whole of Sunday the attempt had to be abandoned’.[5]

‘An obstacle surmounter on its hind legs’. The prototype on the inaugural Cradle trip. Don’t forget to pack a newspaper. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of the St Helens History Room.

The effect of this visitor on Weindorfer, who may have imagined himself awakened from years of isolation from tourists and supplies, can also be imagined. In preparation for the following summer’s business, Lade then built a shed to house the Kegresse at Moina, about three-quarters of the way to Cradle Valley, the idea being to use conventional transport to bring passengers from the coast that far, swapping to the Kegresse only for the challenging final section. The prospects for tourism seemed rosy. At the time, Weindorfer’s friend Ronald Smith was building a family shack on his own land at the edge of Cradle Valley. ‘Have you finished your place?’, Weindorfer, who called the Kegresse the ‘platypus motor’, asked Smith in October 1924. ‘There might be some business for you’.[6]

Gustav Weindorfer. Photo by Ron Smith courtesy of Charles Smith.

Waldheim Chalet in the snow during the Weindorfer era. CF Monds photo courtesy of DPIPWE.

The ‘platypus motor’ made four further trips to Cradle in the period January–March 1925. However, tank technology did not take root on the slopes of Cradle Valley or on the road to Cradle. Snowfalls were too inconsistent to attract skiers, and the Citröen-Kegresse disappeared from service after only one further trip, in December 1927.[7] Weindorfer stuck to his skis and joined the Indian corps instead. In 1931 he acquired an Indian Scout motorcycle, meaning that, for the first time, he could motor to and from Cradle Valley at will.

At least, that was the theory. Weindorfer was found dead next to his Indian half a kilometre from Waldheim in May 1932. It appeared that he had suffered a heart attack while trying to kick start the machine.[8] Cradle’s isolation had finally silenced him.

[1] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 17 July 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [hereafter TAHO]).

[2] See, for example, John Reynolds, André Citröen: the man and the motor cars, Alan Sutton, 1996.

[3] ‘Motor demonstrations’, Advocate, 9 April 1924, p.2.

[4] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 12 April 1924 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [hereafter QVMAG]).

[5] ‘To Cradle Mountain by tractor’, Daily Telegraph, 19 April 1924, p.16.

[6] Gustav Weindorfer to Ronald Smith, 2 October 1924, p.141, LMSS150/1/1 (LINC Tasmania, Launceston).

[7] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 13 December 1927 (QVMAG).

[8] See Esrom Connell to Percy Mulligan, 20 September 1963, NS234/19/1/22; and the coronial enquiry into Weindorfer’s death, AE313/1/1 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 14/01/17 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian landscape photography, Tasmanian nature tourism history

‘The darkroom at Lake St Clair’, HJ King despairs over the photography facilities, 1917. HJ King photo, courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

The young Herb (HJ) King was a rev-head with an artist’s eye, a man beguiled by cameras and carburettors. The frontage of his father’s motorcycle shop, John King and Sons, which he eventually took over, remains a landmark of the Kingsway, off Brisbane Street, Launceston, long after it closed. In 1921 the rival Sim King’s motorbike shop at the other end of Brisbane Street ran an advert for machines with ‘double-seated’ sidecars: ‘Take her with you!’[1] That is exactly what Herb King was already doing, the sight of his wife Lucy in the sidecar of his Indian motorbike becoming a signature of his photography in the period 1919–25.

It was perhaps King’s conservative Christadelphian faith that determined that he marry young, have children and place the role of family man before all else. He married Lucy Minna Large in Hobart in December 1918. Lucy recalled that King drove her father from Hobart to Launceston. Alighting from the car, Charles Large said ‘Oh, my boy, it’s a long way’, to which King replied, ‘Yes, Charles, what about letting Lucy and I get married at Christmas, instead of waiting?’ She was eighteen years old. He was 26.[2]

Lucy in the sidecar at Moina, just off the Cradle Mountain Road, 1919. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

After this, before their first child was born, Lucy was a feature of King’s photography, accompanying him on most of his photographic trips. King got to Cradle Mountain slightly ahead of his nature-loving friends Fred Smithies and Ray McClinton. In December 1919 Herb, Lucy, her sister and a friend started for Cradle on motorbike and sidecar. After staying a night at Wilmot, they had Christmas dinner at Daisy Dell, Bob Quaile’s half-way house, with Lucy making a success of her first Christmas pudding. The track from Daisy Dell across the Middlesex Plains to Cradle Valley was so rough that Quaile bore most visitors along it on various horse-drawn wagonettes. Lucy recalled that on this occasion he was equipped with a two-seater:

‘He could only take one passenger and himself, and he had a horse for other people to ride. I had grown up on a farm and I was happy to ride, but my sister wouldn’t get on, and my husband got on one side and got off the other, and said ‘That’s all I’m having’. We arrived at Cradle Mountain with pounds of sausages around someone’s neck because it had rained and washed the paper off … ‘[3]

This was King’s first meeting with Gustav Weindorfer, the proprietor of Waldheim Chalet at Cradle Valley, who was then campaigning to establish a national park at Cradle Mountain. Weindorfer guided the Kings to the summit of Cradle, and it was there, with numerous peaks and Bass Strait spread out before him, that King’s plan to map the country by aerial photography was developed. ‘It was a glorious day’, King recalled, but the ‘progressive’ man of machines was impatient with foot transport:

‘ … as the afternoon was now getting on, we made a laborious descent over the great boulders and across the plateau to Waldheim. How slow the travelling was!—nearly three hours to cover a short three miles—but amidst such scenery we made light of it. We said to ‘Dorfer’ (as he afterwards became known to his friends): ‘Just fancy; if we had a ‘plane we could do the distance in under three minutes …’ Afterwards we talked as we sat inside the great fireplace of the possibilities of preparing an aerodrome in Cradle Valley, and of landing in Lake Dove with a seaplane’.[4]

Car trouble for McClinton on the road to the Wolfram mine, Easter 1920, with (left to right) Paddy Hartnett and Fred Smithies helping out; Lucy King ensconced in the Indian sidecar; and either Ida Smithies or Edith McClinton blurred in motion in the foreground. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Lucy looking distinctly unimpressed on the road to Pelion at Easter 1920: was it the rough ride or the close attention that dismayed her? HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Lucy’s passive role in King’s photos belies that she could not only ride a horse, but was the first Hobart woman to own a motorcycle driver’s licence. She proved her mettle as a walker, too, when at Easter 1920 the Kings visited Pelion Plain and the upper Mersey River, with Fred and Ida Smithies, Ray and Edith McClinton, and Paddy Hartnett as a guide. This was the first time motor vehicles—that is, McClinton’s Chevrolet and King’s Indian—had entered the valley of the upper Forth River. The steep, rutted climb out of Lemonthyme Creek defeated the car until Hartnett cut wooden blocks to support the wheels. The guide also cleared a large tree off the track next day, after the party had spent a night at ‘the Farm’, that is, Mount Pelion Mines’ hut and stables near Gisborne’s Farm. The ‘Bark hut’, 3 km north of the Lone Pine wolfram mine (aka the Wolfram mine), was the terminus for the vehicles. Only Hartnett’s ingenuity and McClinton’s kit bag of cross-cut saw, axe and shovel got them that far. Now they started on foot for the mine and beyond that the Zigzag Track to the copper mine huts at Pelion Plain, a pack horse carrying much of their gear.[5] Lucy recalled walking

‘eight miles in the pouring rain and when he reached the hut at the top nobody had a dry stitch. Fortunately for the ladies there were two trappers there, and they obligingly said, ‘You come into the hut where this fire is, and get yourselves dried out, and the men will go to the other hut and make a fire for the same purpose’. The next morning when we woke up it was one of the most beautiful sights that was possible. There wasn’t a blade of grass that wasn’t covered in snow’.[6]

Mount Oakleigh and Old Pelion Hut, still with their dusting of snow, Easter 1920. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

That view included Mount Oakleigh, which Herb King photographed. Members of the party visited Lake Ayr and the head of the Forth River Gorge before starting on the return journey.[7]

‘The huntsman’s story’, taken in the mine workers’ hut at Pelion Plain, with (left to right) Ray McClinton, Paddy Hartnett, Lucy King, HJ King, Ida Smithies and Fred Smithies. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Although Paddy Hartnett never used the media, he was equally significant as Weindorfer in the development of a Cradle Mountain‒Lake St Clair National Park. Hartnett’s Du Cane Hut, also known as Cathedral Farm and Windsor Castle, was effectively his Waldheim, a tourist chalet among the mountains. King’s treks to Cradle Mountain and Pelion with their respective guides were transformational in the sense that, although he never became a hardened bushwalker like his fellow photographers Spurling, Smithies and McClinton, he did become a promoter of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park proposal. McClinton photos from this trip appeared in the Weekly Courier, and he, Smithies and King lantern lectured about the proposal.[8]

A slide survives of King promoting himself as a nature photographer, suggesting that he toyed with the idea of turning professional. Presumably, he decided it would not pay. The Kings were a very conservative family. His grandmother, said to be the first Christadelphian in Tasmania, was reputedly disgusted by King’s spending on photographic materials. Perhaps family influenced his choice of career. It is possible that the family motorcycle business seemed a safer bet, or that he felt obliged to follow in his father’s footsteps. Ultimately, people, family and faith meant more to King than any machine or any gadget. It was probably not just for artistic purposes—the compositional need for a foreground—that he placed Lucy in so many of his images. It signalled that she was foremost in his thinking.

[1] See, for example, Sim King advert, Examiner, 2 July 1921, p.14.

[2] Lucy King, transcript of an interview by Ross Case, 18 March 1993, OH18 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [hereafter QVMAG]).

[3] Lucy King, transcript of an interview by Ross Case, 18 March 1993, OH18 (QVMAG).

[4] HJ King, ‘A flight to the Cradle Mountain’, Weekly Courier Christmas Annual, 3 November 1932, p.12.

[5] ‘Motors, cycles and push bikes’, Daily Telegraph, 17 April 1920, p.5.

[6] Lucy King, transcript of an interview by Ross Case, 18 March 1993, OH18 (QVMAG).

[7] ‘Motors, cycles and push bikes’, Daily Telegraph, 17 April 1920, p.5.

[8] See Weekly Courier, 15 July 1920, p.24. McClinton’s photos of the Easter 1920 trip with the Kings, Smithies and Hartnett was used here to illustrate part one of George Perrin’s account of a January 1920 trip into the same country with his wife, Florence Perrin, their friend Charlie MacFarlane and Hartnett (‘Trip to Tasmania’s highest tableland’, Weekly Courier, 8 July 1920, p.37).