by Nic Haygarth | 22/01/17 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian landscape photography

Up one side … a Citröen-Kegresse on the Kensington Sandhills near Sydney. From the Weekly Courier, 27 September 1923, p.23.

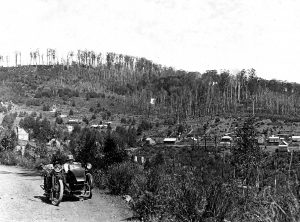

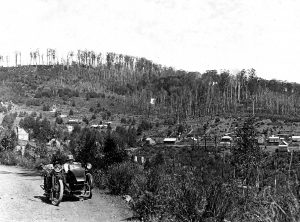

Down the other …. the Citröen-Kegresse prototype on its way to Waldheim, 1924. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Anton Lade.

They don’t make Citröens like that anymore. Gustav Weindorfer of Waldheim Chalet, the highland resort at Cradle Valley, beat the snow by shooting for meat on skis when he began living there in isolation in 1912.[1] At around the same time, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia understandably ordered a grander hunting vehicle for snow conditions—with caterpillar tracks for back wheels. Hannibal’s elephantine passage through the Alps to surprise the Romans had nothing on the Citröen-Kegresse, the assault vehicle which resulted from the meeting of French car manufacturer André Citröen and the Tsar’s resourceful mechanic, Adolph Kegresse, after the Russian Revolution.[2]

The Tsar’s caterpillar-tracked hunting technology now drove a prototype that breached the Himalayas en route to China and crossed the Sahara to Timbuktu. It also took a crack at Cradle. In 1924 Latrobe garage owner William Lade publicised his acquisition of a Citröen-Kegresse in Wynyard, Penguin, Latrobe and Devonport, being fined in the last town for demonstrating its ability to climb the steps of the Seaview Hotel.[3] There were fewer rules and few police in the highlands. Rearing over hills and plummeting down the other side, Lade’s vehicle roared up to Waldhiem with ten people aboard close to midnight on 12 April 1924.[4] Launceston’s Daily Telegraph newspaper had high expectations of the Citröen-Kegresse trip:

‘It had been expected that the machine would attempt the last 1½ miles [from Waldheim] to the [Cradle Mountain] summit, but as the rain continued to fall throughout the whole of Sunday the attempt had to be abandoned’.[5]

‘An obstacle surmounter on its hind legs’. The prototype on the inaugural Cradle trip. Don’t forget to pack a newspaper. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of the St Helens History Room.

The effect of this visitor on Weindorfer, who may have imagined himself awakened from years of isolation from tourists and supplies, can also be imagined. In preparation for the following summer’s business, Lade then built a shed to house the Kegresse at Moina, about three-quarters of the way to Cradle Valley, the idea being to use conventional transport to bring passengers from the coast that far, swapping to the Kegresse only for the challenging final section. The prospects for tourism seemed rosy. At the time, Weindorfer’s friend Ronald Smith was building a family shack on his own land at the edge of Cradle Valley. ‘Have you finished your place?’, Weindorfer, who called the Kegresse the ‘platypus motor’, asked Smith in October 1924. ‘There might be some business for you’.[6]

Gustav Weindorfer. Photo by Ron Smith courtesy of Charles Smith.

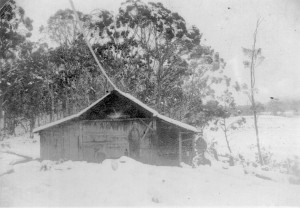

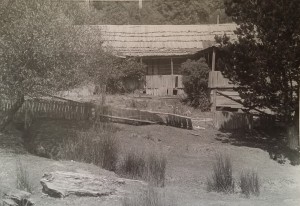

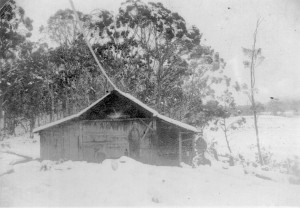

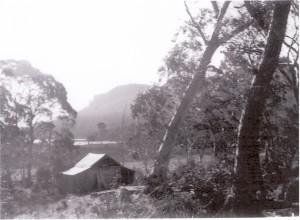

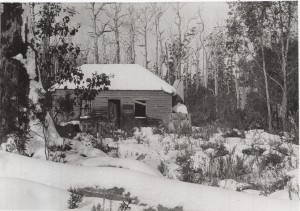

Waldheim Chalet in the snow during the Weindorfer era. CF Monds photo courtesy of DPIPWE.

The ‘platypus motor’ made four further trips to Cradle in the period January–March 1925. However, tank technology did not take root on the slopes of Cradle Valley or on the road to Cradle. Snowfalls were too inconsistent to attract skiers, and the Citröen-Kegresse disappeared from service after only one further trip, in December 1927.[7] Weindorfer stuck to his skis and joined the Indian corps instead. In 1931 he acquired an Indian Scout motorcycle, meaning that, for the first time, he could motor to and from Cradle Valley at will.

At least, that was the theory. Weindorfer was found dead next to his Indian half a kilometre from Waldheim in May 1932. It appeared that he had suffered a heart attack while trying to kick start the machine.[8] Cradle’s isolation had finally silenced him.

[1] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 17 July 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [hereafter TAHO]).

[2] See, for example, John Reynolds, André Citröen: the man and the motor cars, Alan Sutton, 1996.

[3] ‘Motor demonstrations’, Advocate, 9 April 1924, p.2.

[4] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 12 April 1924 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [hereafter QVMAG]).

[5] ‘To Cradle Mountain by tractor’, Daily Telegraph, 19 April 1924, p.16.

[6] Gustav Weindorfer to Ronald Smith, 2 October 1924, p.141, LMSS150/1/1 (LINC Tasmania, Launceston).

[7] Gustav Weindorfer diary, 13 December 1927 (QVMAG).

[8] See Esrom Connell to Percy Mulligan, 20 September 1963, NS234/19/1/22; and the coronial enquiry into Weindorfer’s death, AE313/1/1 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 14/01/17 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian landscape photography, Tasmanian nature tourism history

‘The darkroom at Lake St Clair’, HJ King despairs over the photography facilities, 1917. HJ King photo, courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

The young Herb (HJ) King was a rev-head with an artist’s eye, a man beguiled by cameras and carburettors. The frontage of his father’s motorcycle shop, John King and Sons, which he eventually took over, remains a landmark of the Kingsway, off Brisbane Street, Launceston, long after it closed. In 1921 the rival Sim King’s motorbike shop at the other end of Brisbane Street ran an advert for machines with ‘double-seated’ sidecars: ‘Take her with you!’[1] That is exactly what Herb King was already doing, the sight of his wife Lucy in the sidecar of his Indian motorbike becoming a signature of his photography in the period 1919–25.

It was perhaps King’s conservative Christadelphian faith that determined that he marry young, have children and place the role of family man before all else. He married Lucy Minna Large in Hobart in December 1918. Lucy recalled that King drove her father from Hobart to Launceston. Alighting from the car, Charles Large said ‘Oh, my boy, it’s a long way’, to which King replied, ‘Yes, Charles, what about letting Lucy and I get married at Christmas, instead of waiting?’ She was eighteen years old. He was 26.[2]

Lucy in the sidecar at Moina, just off the Cradle Mountain Road, 1919. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

After this, before their first child was born, Lucy was a feature of King’s photography, accompanying him on most of his photographic trips. King got to Cradle Mountain slightly ahead of his nature-loving friends Fred Smithies and Ray McClinton. In December 1919 Herb, Lucy, her sister and a friend started for Cradle on motorbike and sidecar. After staying a night at Wilmot, they had Christmas dinner at Daisy Dell, Bob Quaile’s half-way house, with Lucy making a success of her first Christmas pudding. The track from Daisy Dell across the Middlesex Plains to Cradle Valley was so rough that Quaile bore most visitors along it on various horse-drawn wagonettes. Lucy recalled that on this occasion he was equipped with a two-seater:

‘He could only take one passenger and himself, and he had a horse for other people to ride. I had grown up on a farm and I was happy to ride, but my sister wouldn’t get on, and my husband got on one side and got off the other, and said ‘That’s all I’m having’. We arrived at Cradle Mountain with pounds of sausages around someone’s neck because it had rained and washed the paper off … ‘[3]

This was King’s first meeting with Gustav Weindorfer, the proprietor of Waldheim Chalet at Cradle Valley, who was then campaigning to establish a national park at Cradle Mountain. Weindorfer guided the Kings to the summit of Cradle, and it was there, with numerous peaks and Bass Strait spread out before him, that King’s plan to map the country by aerial photography was developed. ‘It was a glorious day’, King recalled, but the ‘progressive’ man of machines was impatient with foot transport:

‘ … as the afternoon was now getting on, we made a laborious descent over the great boulders and across the plateau to Waldheim. How slow the travelling was!—nearly three hours to cover a short three miles—but amidst such scenery we made light of it. We said to ‘Dorfer’ (as he afterwards became known to his friends): ‘Just fancy; if we had a ‘plane we could do the distance in under three minutes …’ Afterwards we talked as we sat inside the great fireplace of the possibilities of preparing an aerodrome in Cradle Valley, and of landing in Lake Dove with a seaplane’.[4]

Car trouble for McClinton on the road to the Wolfram mine, Easter 1920, with (left to right) Paddy Hartnett and Fred Smithies helping out; Lucy King ensconced in the Indian sidecar; and either Ida Smithies or Edith McClinton blurred in motion in the foreground. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Lucy looking distinctly unimpressed on the road to Pelion at Easter 1920: was it the rough ride or the close attention that dismayed her? HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

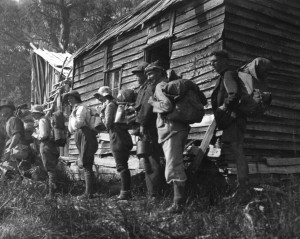

Lucy’s passive role in King’s photos belies that she could not only ride a horse, but was the first Hobart woman to own a motorcycle driver’s licence. She proved her mettle as a walker, too, when at Easter 1920 the Kings visited Pelion Plain and the upper Mersey River, with Fred and Ida Smithies, Ray and Edith McClinton, and Paddy Hartnett as a guide. This was the first time motor vehicles—that is, McClinton’s Chevrolet and King’s Indian—had entered the valley of the upper Forth River. The steep, rutted climb out of Lemonthyme Creek defeated the car until Hartnett cut wooden blocks to support the wheels. The guide also cleared a large tree off the track next day, after the party had spent a night at ‘the Farm’, that is, Mount Pelion Mines’ hut and stables near Gisborne’s Farm. The ‘Bark hut’, 3 km north of the Lone Pine wolfram mine (aka the Wolfram mine), was the terminus for the vehicles. Only Hartnett’s ingenuity and McClinton’s kit bag of cross-cut saw, axe and shovel got them that far. Now they started on foot for the mine and beyond that the Zigzag Track to the copper mine huts at Pelion Plain, a pack horse carrying much of their gear.[5] Lucy recalled walking

‘eight miles in the pouring rain and when he reached the hut at the top nobody had a dry stitch. Fortunately for the ladies there were two trappers there, and they obligingly said, ‘You come into the hut where this fire is, and get yourselves dried out, and the men will go to the other hut and make a fire for the same purpose’. The next morning when we woke up it was one of the most beautiful sights that was possible. There wasn’t a blade of grass that wasn’t covered in snow’.[6]

Mount Oakleigh and Old Pelion Hut, still with their dusting of snow, Easter 1920. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

That view included Mount Oakleigh, which Herb King photographed. Members of the party visited Lake Ayr and the head of the Forth River Gorge before starting on the return journey.[7]

‘The huntsman’s story’, taken in the mine workers’ hut at Pelion Plain, with (left to right) Ray McClinton, Paddy Hartnett, Lucy King, HJ King, Ida Smithies and Fred Smithies. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Although Paddy Hartnett never used the media, he was equally significant as Weindorfer in the development of a Cradle Mountain‒Lake St Clair National Park. Hartnett’s Du Cane Hut, also known as Cathedral Farm and Windsor Castle, was effectively his Waldheim, a tourist chalet among the mountains. King’s treks to Cradle Mountain and Pelion with their respective guides were transformational in the sense that, although he never became a hardened bushwalker like his fellow photographers Spurling, Smithies and McClinton, he did become a promoter of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park proposal. McClinton photos from this trip appeared in the Weekly Courier, and he, Smithies and King lantern lectured about the proposal.[8]

A slide survives of King promoting himself as a nature photographer, suggesting that he toyed with the idea of turning professional. Presumably, he decided it would not pay. The Kings were a very conservative family. His grandmother, said to be the first Christadelphian in Tasmania, was reputedly disgusted by King’s spending on photographic materials. Perhaps family influenced his choice of career. It is possible that the family motorcycle business seemed a safer bet, or that he felt obliged to follow in his father’s footsteps. Ultimately, people, family and faith meant more to King than any machine or any gadget. It was probably not just for artistic purposes—the compositional need for a foreground—that he placed Lucy in so many of his images. It signalled that she was foremost in his thinking.

[1] See, for example, Sim King advert, Examiner, 2 July 1921, p.14.

[2] Lucy King, transcript of an interview by Ross Case, 18 March 1993, OH18 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [hereafter QVMAG]).

[3] Lucy King, transcript of an interview by Ross Case, 18 March 1993, OH18 (QVMAG).

[4] HJ King, ‘A flight to the Cradle Mountain’, Weekly Courier Christmas Annual, 3 November 1932, p.12.

[5] ‘Motors, cycles and push bikes’, Daily Telegraph, 17 April 1920, p.5.

[6] Lucy King, transcript of an interview by Ross Case, 18 March 1993, OH18 (QVMAG).

[7] ‘Motors, cycles and push bikes’, Daily Telegraph, 17 April 1920, p.5.

[8] See Weekly Courier, 15 July 1920, p.24. McClinton’s photos of the Easter 1920 trip with the Kings, Smithies and Hartnett was used here to illustrate part one of George Perrin’s account of a January 1920 trip into the same country with his wife, Florence Perrin, their friend Charlie MacFarlane and Hartnett (‘Trip to Tasmania’s highest tableland’, Weekly Courier, 8 July 1920, p.37).

by Nic Haygarth | 13/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

In May 1914 Ron Smith’s former Forth mate Ted Adams invited him to go hiking at Lake St Clair. Smith, who would be one of the major figures in the establishment of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park, could not make the appointed time.[1] He had business to attend to at Cradle Valley, but perhaps when that was done a cross-country short-cut would bring them together. ‘I thought … I could go overland to Lake St Clair to meet you there’, he told Adams.[2] It was perhaps in that instant that Ron Smith conceived the idea of the Overland Track between Cradle Valley and Lake St Clair. Ironically, it would take him another 27 years to walk it.

The opportunity finally came in late December 1940. Now fifty-nine years old and an invalid pensioner as the result of World War I service, Smith was also the secretary of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board, a land owner at Cradle Mountain and the major documenter of the area’s European history, flora and fauna. The Overland Track, the southern section of which was roughly marked by Bert Nichols in 1931, had only become suitable for independent travellers in 1935–36 after additional track and hut work by Nichols, Lionel Connell and his sons.[3] Few people had then taken up the challenge of tramping a track that now attracts about 10,000 per year from all over the world.

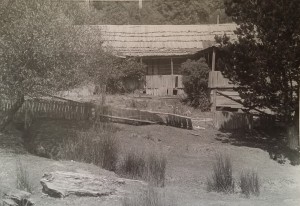

Ron’s early trips from his home at Forth to Cradle Mountain were accomplished on bicycle and on foot, with stopovers at Middlesex Station, but in 1940 he was able to drive from his new home at Launceston to Waldheim Chalet, Cradle Valley, in less than five hours. From 1925 to 1936 the Smiths had had their own house at Cradle Valley, and they would have one again, Mount Kate house, from 1947.[4] However, in 1940 they were content to stay in the late Gustav Weindorfer’s Waldheim Chalet, then managed by Lionel and Maggie Connell. In fact it was almost a second home for the Smith family, since Ron’s oldest son, whom he called Ronny, and Kitty Connell, daughter of Lionel and Maggie, were courting. And yet, despite the stringencies imposed by the war raging in in Europe, people continued to enjoy the major holiday period of the year. On Christmas Day 1940 Waldheim was bursting at the seams with hikers, 50 guests in all. What a peaceful Christmas for head chef Maggie Connell! Ron slept on a sofa in the dining room, his sixteen-year-old son Charlie on the floor of the same room.

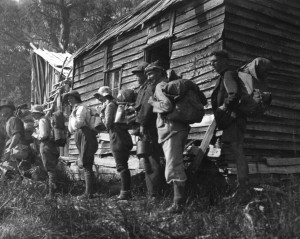

Ron Smith was always a formidable record keeper, and in his diary he recorded with typical precision that he and Charlie were on their way at 7.38 next morning, each of their knapsacks weighing 40 lbs (18 kg). After regular bouts of illness, Ron possibly doubted his own endurance. Two fit young men, Wally Connell and Ronny Smith, carried those heavy packs up to Kitchen Hut, sparing the hikers the full rigours of the tough climb up the Horse Track. After breakfast, Ron and Charlie continued alone, being passed by a party of five women who had started from Waldheim after them. Kitchen Hut was then only a three-sided shelter. There was no proper hut between Waldheim and Lake Windermere, making day one of an Overland Track trip a long and potentially dangerous one. Ron and Charlie reached Waterfall Valley before meeting their first fellow hikers—two young Sydney men—walking in the opposite direction (from Lake St Clair to Cradle Mountain, now prohibited).

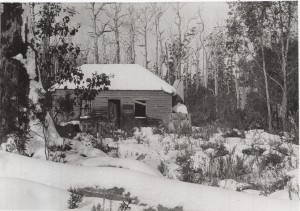

The old miners’ hut at Lake Windermere, 27 December 1940. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

A Fred Smithies shot showing the rest of the old Windermere Hut, taken during an Overland Track tramp. Courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

Father and son reached the Connells’ new Windermere Hut at 4.23 pm, nearly nine hours after setting out from Waldheim. The party of five women camped outside, leaving the hut to the men—and two grey possums, which entered, in what became Windermere tradition, via the chimney in their quest for food. Next morning, Ron and Charlie visited the c1901 Windermere miners’ hut, now in ‘great disrepair; the chimney fallen down and the roof very leaky’. Ron had reached the old hut with Gustav Weindorfer in 1911 and 1914; it was the furthest south he had so far travelled on the route of what became the Overland Track.[5]

Day two, from Windermere along the watershed of the Forth and the Pieman, then around the Forth Gorge and through to Pelion Plain, was another tiring one. They boiled the billy for lunch on the edge of the forest at Pine Forest Moor, with the dolerite ‘organ pipes’ of Mount Pelion West looming large ahead of them. At New Pelion Hut they re-joined the party of five women, greeted a married couple called Calver who arrived from Lake St Clair, plus four Victorian men who were returning to Waldheim after climbing Mount Ossa. There were ten in the Connells’ new hut, which had two rooms so that men and women could be separated. For Ron every new meeting was noteworthy. Names and sometimes addresses were exchanged, and it was a chance to chat and learn. The leisurely experience was far removed from that of more recent times, when the two-way traffic could make the Overland Track feel rather like a scenic Hume Highway.

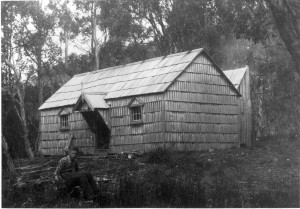

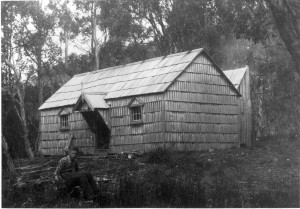

Flourishes of Federation Queen Anne and Arts and Crafts architecture in the Connells’ King Billy pine shingle New Pelion Hut, 28 December 1940, Charles Smith in the foreground. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

With rain threatening, the Smiths decided to spend a day close to shelter at Pelion. Ron had now ventured further south than his departed friend, Gustav Weindorfer, who had taken the census at the Pelion copper mine and climbed Mount Pelion West in April 1921.[6] The mine manager’s hut (Old Pelion) and the workers’ hut from that period were both in good repair. Leaving these huts, Ron and Charlie crossed Douglas Creek and followed the southern edge of Lake Ayr until they met the Mole Creek (Innes) Track near the rock cairns and poles marking the then Cradle Mountain Reserve’s eastern boundary.

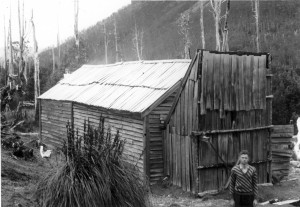

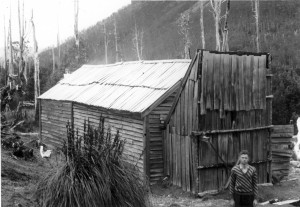

Tommy McCoy’s hunting hut near Lake Ayr. Photo courtesy of the McCoy family.

McCoy’s hut as it looked in 1951, with Mount Oakleigh and Lake Ayr for a backdrop. Photo courtesy of the McCoy family.

The reserve had been a bird and animal sanctuary since 1927. Yet, cheekily poised about 250 metres beyond the boundary, Tommy McCoy’s new hardwood paling hunting hut made his intentions clear. Hobart hikers would become conservation activists, puncturing McCoy’s food tins with a geological pick, when they came across his hut in 1948.[7] However, the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary, a former possum shooter and a man of a different ilk, was much more respectful, leaving payment of threepence for a candle he removed from McCoy’s camp. Ron and Charlie also inspected the old post-and-rail stockyard near the western end of Lake Ayr on their way back to New Pelion. On their second night at Pelion propriety was dispensed with, as the Smiths and Calvers shared a room, leaving the other room for newcomers.

An unsympathetically cropped image of the two-room Du Cane Hut, 29 December 1940, with Cathedral Mountain omitted but Charles Smith in the foreground. Ron Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

An earlier Ray McClinton or Fred Smithies shot of the original one-room Du Cane, taking full advantage of the view of Cathedral Mountain.

The party of five women motored past the Smiths on the climb up to Pelion Gap next day, marching right through to Narcissus Hut, a distance of about 27 km in a day. Ron and Charlie took a leisurely pace, visiting Kia Ora Falls and camping at Du Cane Hut (Windsor Castle or Cathedral Farm), Paddy Hartnett’s old haunt, which had been converted to a two-room building in keeping with New Pelion. Reflecting, perhaps, his reduced stamina, Ron elected to wait on the main track while Charlie viewed Hartnett Falls. The pair also made a diversion to Nichols Hut, the walkers’ hut Bert Nichols had erected beside his old hunting hut. For a man who in his younger days rarely left a bush setting or bush person unsnapped, Ron Smith was relatively parsimonious with his photos on this trip, neglecting these buildings, McCoy’s hut and the old Mount Pelion Mines NL huts. He appears to have been ignorant of the other hunters’ huts located near the track between Pelion Plain and Narcissus River.

Ron and Charlie were accompanied most of the way from Pelion to Narcissus Hut by the Robinsons, a Sydney couple they had first met at Waldheim. Crossing the suspension bridge over the Narcissus River, Mrs Robinson’s hat landed in the drink and disappeared, despite a group rescue effort. Narcissus Hut, the staging post for the motorboat trip down Lake St Clair, as it is today, replicated the situation at Waldheim, being full to the brim and beyond, with numerous tents being pitched outside. Among the hikers were the economist and statistician, Lyndhurst Giblin, and HR Hutchinson, Chairman of the National Park Board, the subsidiary of the Scenery Preservation Board which oversaw the Lake St Clair Reserve. Indeed, it must have seemed like the veritable busman’s holiday when the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary met the Lake St Clair Reserve Board chairman on the Overland Track that united their realms.

Bert Fergusson’s motorboat loading at Narcissus Landing, 31 December 1940. Seventeen to board, including the party of five women, and a tentative Charles Smith (fourth from right). Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The trip was concluded in six days. It took 1 hour 45 minutes to traverse Lake St Clair in the famous Bert ‘Fergy’ Fergusson motorboat on New Year’s Eve, 1940. This seems extraordinarily slow progress—didn’t Paddy Hartnett row the lake faster than that 30 years earlier, against the wind?— until you realise how overloaded Fergy’s vessel was! Seventeen people were crammed aboard what was certainly not Miss Velocity. Ron and Charlie slept in Hut Twelve of Fergy’s tourist camp at Cynthia Bay, where a housekeeper, Mrs Payne, was also employed. From here Fergy operated a free ‘bus’ service (Jessie Luckman called it a ‘frightful old half bus’ sporting sawn-off kitchen chairs with basket-work seats) to Derwent Bridge, where the departing tourist joined one of Grey’s buses. The Lake St Clair tourist infrastructure of 76 years ago was surprisingly well organised. Charlie having departed with family members, Ron stayed on a day more and caught a bus back to Launceston via Rainbow Chalet at Great Lake and Deloraine, using a short stopover in that town to submit a butcher’s order for Fergy. All this recreational transport at a time when petrol was rationed for the war effort!

On 3 January 1941 Ron Smith rested at home, having at last completed the journey contemplated 27 years earlier. Perhaps the experience strengthened his belief in the need for a motor road from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair, thereby conferring universal reserve access.[8] Age may not have wearied him, but maybe at that moment his swollen right foot felt more comfortable on an accelerator than in a heavy boot.[9]

[1] See ‘Ron Smith: bushwalker and national park promoter’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.132–59.

[2] Ron Smith to GES Adams, 15 May 1914, NS234/17/1/4 (TAHO).

[3] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men, pp.122–27.

[4] See ‘Smith huts’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.36–43.

[5] For the 1911 trip, see Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 29 November and 1 December 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO). The pair’s arrival at the Windermere Hut in 1914 had scared the life out of its incumbent, miner/hunter Mick Rose, who feared he had been he had been nabbed engaging in out-of-season snaring.

[6] Gustav Weindorfer diary, NS234/27/1/8 (TAHO); ‘Mountain beauties: Tasmania’s charms’, Examiner, 6 January 1934, p.11.

[7] Interview with Jessie Luckman.

[8] See, for example, minutes of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board meeting, 25 June 1947, AA595/1/2 (TAHO).

[9] This account of Ron and Charlie Smith’s walk on the Overland Track is derived from Ron Smith’s diary, NS234/16/1/41 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 05/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Stanniferous drift is a term once used to describe tin-bearing ground, but it could just as easily describe the movement of tin mining families—or mining families of any other stripe—from one field to the next in search of better opportunities. Both economics and personal tragedy prompted depopulation of the small Middlesex mining field in north-western Tasmania around the time of World War I (1914–18). The contemporary photographs of bushwalker and national park promoter Ron Smith help tell the tale.

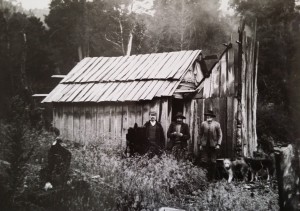

Hut at the Iris tin mine, April 1905. (Left to right) Les Smith, Tom Murphy and Richard Kirkham. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Wooden sluicing pipes, Iris tin mine, 1990s.

Hut at the Iris tin mine, 1990s.

In Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, Simon Cubit and I told the story of the three Davis brothers, Clarence, Sidney (Sid) and Edmund (Eddie), who came to Tasmania from Victoria and tried to farm the Vale of Belvoir near Cradle Mountain in 1903.[1] When the farming venture failed, Clarence Davis returned home, but Boer War veteran Sid Davis (1879–1913) and Eddie Davis (1888–1944) stayed on in the Tasmanian highlands, taking up the lease of the Iris tin mine near Moina.

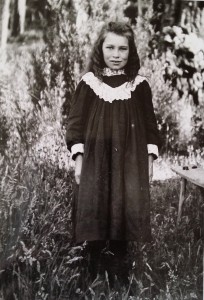

Charlie and Charlotte Adam with their three eldest children, Bell goldfield, 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The Davis brothers’ partner in the mine was Charles Frederick Douglas Adam (c1864–1932).[2] Born in India as the son of an Anglo-Indian lieutenant, Adam had been sent home first to his parents’ house at Dover, England, to an aunt in France and to a Middlesex boarding school.[3] He is also said to have attended Eton, London and Cambridge Universities and the Sandhurst Academy—a busy schedule indeed, if it can be believed—before serving in the 81st Foot Regiment, with which he returned to India. Defective hearing prompted his retirement from the military, and he obeyed medical advice by settling in Australia. After a few years in Tasmania he arrived on the Bell Mount goldfield during the small rush there in 1892.[4] He made minor gold discoveries around the area at Golden Cliff and Stormont, and reworked the Bell goldfield when the hydraulic gold craze hit Tasmania. Charlie Adam married Charlotte Saltmarsh (1873–1946) in the nearby town of Sheffield in 1899.[5] They had children Charles William Guy Adam (1900), Mary Charlotte Adam (1902), Freda Kate Adam (1904), Frederick John Adam (1907), Robert Douglas Adam (1909) and Eileen.[6] There was also Charlotte’s daughter, Elsie (Elizabeth Mary Saltmarsh, born 1896), from a previous relationship.[7] Like many bush people, Charlie Adam used press subscriptions to keep up with the outside world, and his favourite was the weekly English illustrated newspaper The Graphic.[8]

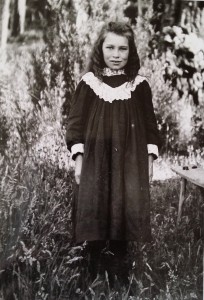

Elsie Adam, Bell goldfield, February 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

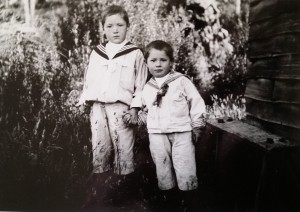

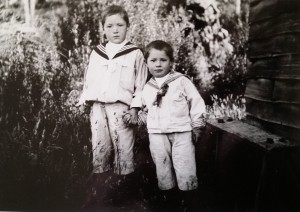

Guy and Mary Adam, Bell goldfield, February 1905. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

However, at a time when there was no school at nearby Moina, the Adams’ most important education supplement was the tutor they employed, Mary Smith, to teach their three eldest children.[9] One of the things Mary taught was propriety. The manager of the biggest mine in the district was William Hitchcock but, offended by his surname, Mary pronounced it ‘Hitchco’. Did her silent ‘ck’ remove the problem or draw attention to it?[10]

Sid Davis came to dinner at the Adam house at the Bell goldfield, met Mary the tutor and began to court her. They married and established a farm at Black Jack, the long straight on what is now the Cradle Mountain Road south of Moina. From here Sid had a short walk to his other work at the Iris tin mine. The couple’s first child, Gladys, did not survive, but they had a second daughter, Hilda, in 1911, and another, Molly, two years later.[11]

Believed to be Sid and Mary Davis on their wedding day, 1909. Courtesy of Maree Davis.

Mary found the isolation difficult. Young Harold Tuson of Lorinna, on the eastern side of the Forth River, found out how lonely she was. In contrast to Charlie Adam’s highly regimented upbringing, this thirteen-year-old had just entered the workforce on a road gang, building the Cradle Mountain Road, and was camped near the Davis house. While returning home for the weekend he ran into Sid Davis on the road:

I suppose he wanted someone to talk to … ‘Where did you come from? And what do you do?’, and … he said, ‘Call in’. Little two-room place on the left … ‘Call in and have a talk to the wife. She’s very, very lonely’. And so on the Monday I did [call in]. And I’m carrying a songbook and she and I got to work and were singing … and I decided I’d better go and she wouldn’t allow me, she didn’t want me to go. ‘Sing another song …’[12]

In 1912 Gustav and Kate Weindorfer established Waldheim Chalet, their tourist resort at Cradle Valley. Charlie Adam was one of their first guests, but Weindorfer also availed himself of the Davises’ hospitality when caught on the road in bad weather. On more than one occasion he rocked young Hilda Davis to sleep in her cradle.[13]

On 14 May 1913 Sid went to work as usual at 7 am. Two-year-old Hilda accompanied her father to the gate. The family’s dog, Bob, followed at Sid’s heels until Mary called him home. She was busy in the kitchen four hours later when she heard a horse galloping up to the house, followed by a knock at the door. It was her friend, a lady named Ward, a frequent visitor. Imagining that she had bad news to impart, Mary immediately thought of her mother. ‘Don’t tell me’, she cried, ‘go and tell Sid!’ ‘I can’t’, her visitor replied, ‘he’s dead’.[14]

Sid Davis had been working in the open cut when a tree stump fell on top of him, striking him fatally on the back of the head. He had survived guerrilla warfare in South Africa only to succumb in a mining trench in peacetime. ‘It was such a blow to Mum, really and truly’, Hilda Davis recalled,

She never got over it … She was always thinking of her days at the mine and of Dad. She never got it out of her system. She loved those days up there …[15]

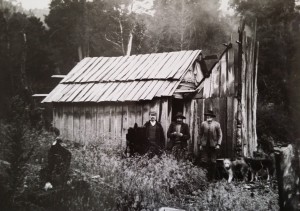

The abandoned Adam house at the Bell goldfield, February 1926. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The deserted Davis house at Black Jack, Cradle Mountain road, August 1925. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Mary Davis tried to keep the Iris mine going, but having a four-month-old child at her breast made it impossible. Tin mining was scuppered by World War I soon after. There was an exodus from the small mining field. Mary Davis tutored children in Sheffield, but eventually returned home to her parents. Eddie Davis married Moina postmistress Lil Gurr, with whom he adjourned to Melbourne.[16] Elsie Adam married miner Watty Davis at her parents’ house but set up home at the tungsten and tin village of Storeys Creek.[17] Charlie and Charlotte Adam moved to Waratah, but eventually resettled in another mining region, the Latrobe Valley, Victoria. Three other Adam children settled in mining towns.[18] By the mid-1920s both the Adam and Davis houses, where so many children had grown and so many lives had intersected, were ruins. Of the characters of this story, only Gustav Weindorfer, the widowed proprietor of Waldheim Chalet, remained trying to eke a living from the mountains.

[1] Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.18–23.

[2] Australian Death Index, registration 13455/1932.

[3] British Census, 1881, Middlesex, Finchley, District 1, p.54. His birthplace was given as India; ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[4] ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[5] Married 10 May 1899, marriage registration 962/1899, Sheffield.

[6] Birth registrations 2326/1900, 2391/1902, 2518/1904 respectively. Frederick John Adam’s death certificate (7866/1972, Victoria) give his year of birth as 1907. Robert Douglas Adam’s World War II military record gives his date of birth as 29 January 1909, place of birth Moina. Eileen Adam is mentioned as a surviving child in Charlie Adam’s obituary, Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

[7] Born 27 August 1896, birth registration 2328/1896, Sheffield.

[8] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[9] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991. Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995, remembered Mary Smith as being the tutor for William and Kate Hitchcock at Moina.

[10] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[11] Rose Ellen Gladys Davis was born 8 January 1910 and died 8 April 1910, birth registration 5417/1910, death registration 928/1910. Hilda May Davis was born 2 March 1911: Molly Davis was four months old at her father’s death: both facts from interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[12] Interview with Harold Tuson, Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[13] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[14] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[15] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[16] Interview with Hilda Amos, née Davis, daughter of Sidney and Mary Davis, by Len Fisher, 21 September 1991.

[17] See ‘Wedding bells’, Examiner, 12 April 1920, p.6.

[18] ‘Mr Chas FD Adam, Yallourn, Vic’, Advocate, 8 February 1933, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 10/10/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Black’s adit, Black Bluff gold mine, Lea River, north-western Tasmania.

In summer you can easily wade up the Lea River beneath the beetling cliffs along the northern edge of the Middlesex Plains. Only by then doubling back can you find a mullock dump partially blocking the river, and above it a 30-metre-long tunnel into the cliff, where the remains of a skip and a rusted lantern testify to the past use of the rotten wooden rails. The price of gold is attractive in depression times, and it was in the wake of the 1891 depression that Lou Thomas first struck gold here. In 1931, during the Great Depression, depreciation of the pound boosted the gold price, an action repeated in 1952. Each time the miners returned hoping to plunder the Black Bluff or Lea River reef that had failed to yield its treasure last time around. Others, like Cliff ‘Dingo’ Beswick in the 1960s, chipped away in the main adit as a hobby, bothering more nesting swallows than gold buyers.

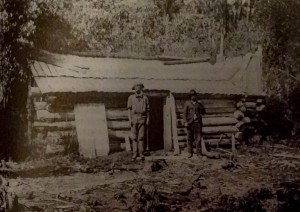

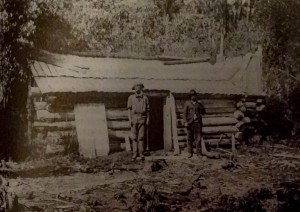

Dick Brown and George Francis, of Middlesex Station, renovating the log hut at the Black Bluff gold mine to accommodate Walter Malcolm Black, 1905. RE Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

The mine’s only long-term resident, Walter Malcolm Black (1864–1923), probably spent a thousand pounds or so here. He was a remittance man—his family paid him to stay away from them. Black was the second son of grazier Archibald Black of Gnotuk, near Camperdown, Victoria, and a nephew of powerful Victorian squatter Niel Black.[1] Of medium build, 70 kg and 177 cm tall, Black was raised in the Presbyterian faith of his Scottish ancestry and, like many a grazier’s son, he was educated at the prestigious Geelong Grammar.[2]

In 1885, at 21 years old, he won an out-of-court settlement over his late father’s estate, which amounted to government debentures worth £7124.[3] The terms of settlement apparently included a deal that he stay well away from home.[4] His crime against his family, if there was one, is unknown, but in 1886 he was a grazier at Lila Springs Station, in the Warrego district, New South Wales, and in 1891 he was out at Bourke.[5]

Black’s later movements give the impression of being directed by the need of distraction. His nest egg probably satisfied his financial needs. By 1894 he had renounced grazing for a mining career, possibly at the Western Australian gold rushes. In 1905 he was in Tasmania, occupying Lou Thomas’ recently renovated log hut at the top of the 90-metre-high cliff in which several drives sought that elusive lode. His introduction to the Middlesex Plains area was probably Deloraine doctor Frank Cole, who at one stage applied for land at Lake Lea, where he was said to be planning a summer resort and sanatorium.[6] The area Cole applied for later became known as Blacks White Grass, and Black was said to be the owner of a boat on Lake Lea.[7] In 1909 he asked the Meteorological Office of the Department of Home Affairs to send him a rain gauge, which he attended conscientiously for six years.

Louisa Brown with pet wallaby at Middlesex Station, 1910. RE Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

Black soon met his closest neighbours, Middlesex Station tenants Frank and Louisa Brown, plus William Hitchcock, manager of the Shepherd and Murphy tin, tungsten and bismuth mine at Moina. Later, Cradle Mountain enthusiast Gustav Weindorfer joined him in the high country. Educated men, Hitchcock and Weindorfer were important contacts because they were fellow converts to the ‘bush brotherhood’ and enabled an exchange of news, books and magazines. Illuminating titles like When earth was young, The great age, Waterfall and the Bulletin helped them keep a fragile hold on what must sometimes have seemed a world far removed. Black loved botany. For recreation, he could ramble up the Lea River in search of Blandfordia blooms with his sheepdog, take a row on Lake Lea, or track down his grey horse, Blue Spec, named after the 1905 Melbourne Cup winner, who roamed the woods with a bell around his neck.

Fury hut, Fleece Creek, 1910: Gustav Weindorfer, Walter Malcolm Black, Kate Weindorfer. RE Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

However, Black is best known for his part in a legendary 1909–10 Cradle Mountain expedition. Kate Weindorfer, Ron Smith, Black and his sheepdog were there on the Cradle summit in January 1910 when Gustav Weindorfer proclaimed the need for a national park ‘for the people for all time’. This statement anticipated the establishment of both Waldheim (‘forest home’) Chalet at Cradle Valley and today’s Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park.

Black returned to his unnamed log hut. Perhaps because he had scoffed strawberries from Black’s garden, Government Geologist WH Twelvetrees took an optimistic view of the Black Bluff mine when he inspected it in 1912. However, Black never found his gold lode. Frustrated with the mine, he prospected as far afield as Granite Tor and the Dove River gorge, armed with a £75 government advance granted under the Aid to Mining Act (1912). Keeping the rain gauge only seemed to dampen his spirits. ‘I am heartily sick of things here,’ he wrote in 1915, ‘and I want to go down … and take a contract digging spuds—something to do at any rate … Measured 110 points this morning and raining still—over 6 inches this week’. In October of that year Black rewound his age by six years to 45, enabling him to qualify for war service and join up as a private in the First Remounts. He took the rain gauge, his books, his horse, saddle and bridle down the Five Mile Rise to Lorinna and sold them to fellow prospector Syd Reardon for £5.[8] Blue Spec may have passed to another Lorinna identity, Bert Nichols, who was known to use a grey mare by that name to transport his wallaby and possum skins.

Black served his time in Egypt without seeing the battlefront. However, war service aggravated a susceptibility to pleurisy which he had first contracted in Australia. At Heliopolis, Cairo, in 1916 he was struck by a galloping horse, breaking two ribs and damaging others. After that, every cold he caught turned into pleurisy, a condition which was exacerbated by another rib injury sustained when he fell down a manhole while aboard the Devon on his way home to Tasmania. Black spent ten days in hospital upon arrival in Hobart, and was discharged as permanently unfit in January 1919.[9] However, instead of returning to Black Bluff, he took advantage of the Returned Soldiers Settlement Act (1916) by market gardening a free land selection at Tolosa Street, Glenorchy. His restless ways continued. Soon he was grazing at Bellerive.[10] After a stint working at the cement works on Maria Island, he was admitted to the no.9 Military (Repatriation) Hospital, Hobart, where he died on 31 June 1923 at 58 years of age.[11] He was intestate, his probate being valued at a little more than £19.[12] That family nest egg was long gone.[13]

So was Black’s rain gauge. Syd Reardon was delighted to have it—and not because of an interest in precipitation. The only liquid Reardon cared about came in a bottle. Every month the Meteorological Department sent out a chart on which to plot the rainfall figures. Reardon saved them up and used them to wallpaper his hut. Meanwhile, young Harold Tuson delivered the gauge to the Lorinna State School, where for a time the teacher, Ivy Lloyd, kept up the rainfall records. However, when she fell ill and moved to Bothwell, the meteorology of the Middlesex Plains area drifted back into obscurity.

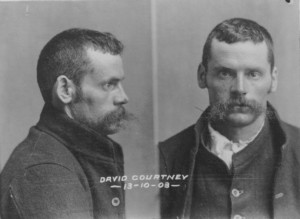

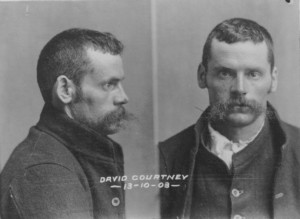

Dave Courtney with the beginnings

of his moustaches, in 1903 mugshots.

From GD63-1-3, TAHO.

Until legendary stockman Dave Courtney came on the scene. How Foley, the Divisional Meteorologist, came to choose the famously sullen Middlesex Station ‘mystery man’ as an ‘observer’ is hard to imagine. Yet their meagre exchanges show Courtney to be the one reliable record keeper in a dynamic tenancy. In August 1928, for example, Foley asked Courtney why no rainfall records had been received from Middlesex Station for six months. The bearded wonder responded that ‘since February last I have been away and the other man who was left in charge did not take the other rain’.

Courtney’s replacement Ted Farrell maintained the records for a time. Sometimes in winter Middlesex was cut off by snow drifts. Foley sent Farrell a snow gauge to measure that as well as the rain, but the stockman had moved on. Next man Bill Ward refused gauge duty, and when in December 1932 Ben Brown took over the station the snow gauge was missing. Alex Burnie replaced Brown in November 1934 and records again lapsed. Burnie left Middlesex, Dave Courtney returned—no rain gauge this time. Where was it? The Meteorological Department tracked down Alex Burnie in Queenstown in 1940, when he denied any responsibility, ‘I left Middlesex in May 1938 and all gauge [sic] were in good order then’.

The family of Middlesex Station grazier JT Field sold the property after his death in 1940. New owner, saw-miller FH ‘Cocky’ Haines, was more interested in millable timber than in raising stock. The station gained a strange new tenant called Frank Whitworth. In April 1946 he asked the Meteorological Department for ‘a suitable outfit for taking rain, temp records’ and a record book. ‘I am taking over a certain portion [of Middlesex] (which will be named Brayfield)’, he wrote. ‘I expect to be here for a considerable time’. Whitworth’s Brayfield letterhead, which included postal, telegram, cable and street addresses, supported this expectation. Unfortunately, one snowy winter at Middlesex consigned Brayfield to history. Whitworth scurried away to the sunnier climes of Port Sorell, taking the gauge with him.

So the rain on the plains splashed silently on the earth again, and the unmeasured hail clanged on the station roof. A hot fire took out Black’s log cabin. An adit packed with ancient, weeping gelignite is all that now signifies the remittance man’s tenancy of more than a century ago, and should a foot fall too heavily in that Lea River eyrie, more than a winter deluge may rain down on Middlesex.

[1] Birth record no.7299/1864, Victoria.

[2] ‘Personal’, Camperdown Chronicle, 9 August 1923, p.2.

[3] ‘Supreme Court’, Age, 27 February 1885, p.6.

[4] Harold Tuson, interviewed at Canberra, 11 May 1995. He met Black many times at the Mail Tree, Middlesex Plains, and once at Lorinna, and recalled that he was a ‘remittance man’.

[5] Notice, New South Wales Government Gazette, 19 March 1886, p.1983; ‘Quarter sessions’, Western Herald, 10 February 1891, p.2.

[6] ‘EJA’ (Dr EJ Addison), ‘On the roof of Tasmania’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 March 1907, p.4.

[7] Ken Cook, interviewed 8 August 1993; ‘LJB’ (Lionel Brown), ‘Middlesex: a tourist resort’, Examiner, 11 February 1909, p.3.

[8] Harold Tuson, interviewed at Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[9] World War I service record. See https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1791278/

[10] Supplemental electoral roll for Commonwealth Subdivision of Franklin, 1919, p.3.

[11] ‘Items of interest’, World, 2 July 1923, p.4.

[12] AD963/1/2, no.1057 (TAHO).

[13] AD963/1/2, no.1057 (TAHO).