Had Tasmanian miner Teddy O’Rourke been an interior decorator, he would have been a shoo-in for a colonial courtroom refit. His familiarity with magistrates’ chambers from Hobart to Deloraine, with dalliances at Kempton, Lefroy , George Town and almost a permanent booking in Launceston, must have been unsurpassed. Unfortunately, he was probably often too drunk to remember the decor. Yet Teddy also seems to have found a way to beat the bottle for two decades.

Edward Martin O’Rourke was born into an Irish Catholic family in Hobart in about 1856. A newspaper report of his mother Eliza (née O’Donnell or Donnell, a convict[1]) leaving home to escape violent attack by his father, ex-convict constable Martin O’Rourke (or Rourke), when he was an infant suggests that his was not a happy, comfortable childhood.[2] His education was probably rudimentary, as he remained illiterate.[3] By the time Martin O’Rourke drowned trying to ford the Forester River in 1876 at the age of 45, Teddy had at least five siblings.[4] It was after that that Teddy, along with his mother and sister Mary Ann Stratton, started making regular appearances in the Launceston Police Court, charged with assault (sometimes of each other), theft and drunk and disorderly behaviour.[5] The Jolly Butchers Hotel in Balfour Street kept by Eliza O’Rourke was the scene of some of this action.[6]

At the age of about 21 Teddy left Launceston for a rollicking lifestyle, racking up fines for public disturbances and learning how to handle a cradle at Brandy Creek, the alluvial goldfield that became Beaconsfield.[7] The only treatment he appears to have received for alcoholism was a stint in the slammer. One assault charge against him was dropped because his delirium tremens made him unable to testify.[8] Finally, in 1883, the judiciary lost patience and he got six months’ gaol for being idle and disorderly—followed by another three months for the same offence, this time in Hobart.[9] He served at least six terms in Hobart’s Campbell Street Gaol.[10]

Yet after 1892 O’Rourke stayed out of trouble for more than 20 years. Was mining his saviour? Men like Syd Reardon and Paddy Hartnett at Lorinna, 20 km from the nearest hotel, are said to have found an escape from the bottle in the bush. Perhaps Teddy’s experience on the Five Mile Rise when it was a diggers’ gold field in the 1880s was literally a sobering one.[11]

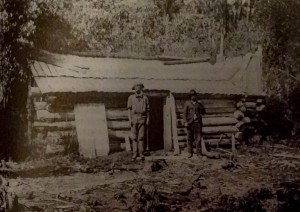

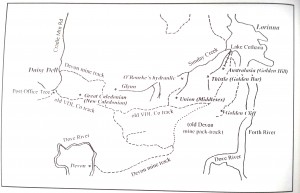

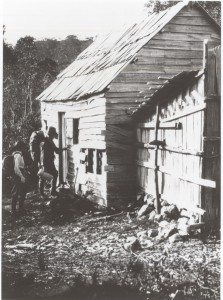

Then in about 1893 the New Zealand hydraulic craze hit Tasmania, and old gold fields like the Five Mile Rise got another trial, this time with the high-pressure hydraulic hose. Teddy O’Rourke took a claim on Sunday Creek, high up the Five Mile Rise, built a hut nearby and embarked on an unusual seasonal regime. Since it was only in the wet season that he could get sufficient water to operate the high-pressure hose, he combined hydraulic sluicing with hunting. April, May and June were the traditional hunting season. Prospectors and miners in the bush generally snared and shot animals for food anyway, but processing their skins for sale would have enabled O’Rourke to maximise (and perhaps sustain) his winters in the bush. A photo of what is probably O’Rourke’s hut taken by Fred Smithies shows that it was equipped with a skin drying chimney typical of those developed in the Cradle Mountain-Middlesex Plains area for the drying of possum and wallaby skins.

Teddy now revealed that not only could he make the press but he could use it. The secret to raising capital, apparently, was constant self-reference in the mining columns of newspapers. Harold Tuson grew up at Lorinna. In 1911, at the age of thirteen, he started work on gangs making tracks and roads in the upper Forth River region. During this time he came to know O’Rourke well as a fellow road worker, one of the latter’s summer jobs. He recalled the ‘big lump of a [Tasmanian-born] Irishman’ speaking with a thick Irish brogue. Having survived two or three bushfires, O’Rourke’s hut was then clearly visible from Lorinna high on the hill. Tuson recalled the miner’s struggle with alcoholism and his appearances in both the legal and mining columns of the newspaper: ‘“O’Rourke’s Hydraulic showing gold freely in the face”. That was one of Teddy’s. He’d write that to the paper to keep it going’.[12] Other stock phrases included ‘sluicing on payable gold’.

Fred Smithies photo, NS573/4/9/32 (TAHO)

O’Rourke’s hut stood near the beginning of the pack track down to the Devon mine in the Dove River Gorge. This pack track had become part of an extraordinarily steep route used by hunters to gain access to the Cradle Mountain region. On the southern side of the Dove River Gorge, the route continued up a steep hill known as Paddys Nut and crossed the Campbell River.[13] This was the route used by hunters Tom Jones and Bert Hansen in the winter of 1905 when the latter was tragically lost in a snowstorm near the lake near Cradle Mountain that now bears his name. Jones reported four-feet-deep snow as he began to make his way out to O’Rourke’s hut to raise the alarm, giving some idea of the conditions the gold miner experienced during these winter stints.[14] Since there are no mining reports to the press from O’Rourke in 1905, hunting may have been his primary activity during that wet season.

He also had business elsewhere. In 1904 O’Rourke had taken up a tungsten claim nearby, and by 1907 he was based at Ringarooma in the north-east, where he discovered the Montrose tin mine.[15] Later he turned his attention to the Colebrook tin field on the west coast, where he held a claim for a Launceston syndicate.[16] Meanwhile, in his absence, his hut on the Five Mile Rise was entered, robbed and forfeited to the Crown.[17] Thus the only property Ted O’Rourke ever owned was lost.

In 1911 he had a child, Edeline O’Rourke, with the recently widowed Annie Bissett (née Garrett) in Launceston.[18] She already had five children! Family responsibilities would have necessitated a steady income, hence, perhaps, O’Rourke’s work on the road gang. Eventually he may have got too old for bush life. Again, he was not at his best in town near the pubs. O’Rourke’s declining years contained a familiar litany of court appearances, including charges of disturbing the peace and vagrancy.[19] In 1919 the 63-year-old was found lying unconscious with a gashed head on a Launceston street.[20] In 1920 he was described as ‘an old habitue’ when defending a charge of being drunk and incapable in Albert Park on Christmas Day and in Charles Street a few days later.[21] He sported a scar over his left eye, perhaps as the result of some drunken escapade.[22] In 1922 he absconded when wanted for non-maintenance of his children, being tracked down in Deloraine.[23] In 1924, at 68 years of age, he was again found drunk and incapable in the street.[24] The trail of self-destruction stops there.

Like so many children of ex-convicts who could never escape the cycle of poverty and alcoholism into which they were born, Ted O’Rourke would have died intestate, with few possessions. His death stirred no comment in the press. Perhaps no one mourned his passing. However, I like to think of him as an innovator. He developed an unusual regime of hose, snare and, perhaps, teetotal, which kept him upright for two decades, drying out when the wet winter season brought his mining claim to life. That counts him as a success!

[1] Eliza O’Donnell was transported on the Midlothian. See permission to marry, 4 April 1855, CON52/1/7, p.408 (TAHO) and marriage certificate 473/1855, Hobart.

[2] ‘Local intelligence’, Colonial Times, 17 March 1857, p.3.

[3] Campbell Street Gaol Gate-book, warrant no.17591, 18 February 1889; records compiled by Laurie Moody; http://www.tasmanianwarcasualties.com/gravesofts%20split/Campbell%20Street%20Gaol/Rural%20Offences%20Part%209.htm

[4] See inquest, POL709/1/13, p.31 (TAHO); ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 20 January 1877, p.3. Martin Rourke was tried at Galway on 23 June 1848, sentenced to seven years, and came to Tasmania on the Lord Balhousie, being pardoned in 1855.

[5] See, for example, ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 21 September 1876, supplement p.2; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 November 1876, p.4.

[6] ‘Quarterly licence meeting’, Launceston Examiner, 8 August 1876, p.3; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 9 November 1876, p.4; ‘No true bill’, Launceston Examiner, 1 March 1877, p.2.

[7] ‘George Town’, Reports of Crime, 5 April 1878, pp.55–56.

[8] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 26 April 1882, p.3.

[9] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 12 November 1883, p.3; ‘City Police Court’, Mercury, 17 December 1884, p.2.

[10] Laurie Moody, ‘Campbell Street Gaol: inmates 1873–1890’, Tasmanian Ancestry, vol.26, no.2, September 2005, pp.24–30.

[11] Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[12] Harold Tuson, interviewed in Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[13] See, for example, ‘North Western notes’, Mercury, 4 August 1905, p.2.

[14] ‘Cradle Mountain mystery’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 September 1905, p.2.

[15] ‘Iris River wolfram field’, Examiner, 20 September 1904, p.2; ‘Discovery of tin’, Examiner, 26 October 1906, p.2.

[16] See, for example, ‘Colebrook tin fields’, Examiner, 24 February 1912, p.4.

[17] POL386/1/1, Daily Record of Crime Occurrences – Sheffield 1901-1916 (TAHO).

[18] Birth registration 4877/1911, Launceston. See ‘Branxholm railway accident’, Mercury, 26 April 1910, p.2.

[19] ‘Police Courts, Hobart’, Mercury, 21 September 1915, p.6; ‘Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 3 November 1916, p.4; ‘City Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 13 April 1917, p.4; ‘City Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 18 June 1918, p.4.

[20] ‘An old age pensioner’s plight’, Launceston Examiner, 26 December 1919, p.4.

[21] ‘City Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 6 January 1920, p.2.

[22] ‘Prisoners to be discharged’, Police Gazette, 9 April 1920, p.69.

[23] ‘Persons enquired for’, Police Gazette, 23 June 1922, p.114; ‘Absconders’, Police Gazette, 14 July 1922, p.127.

[24] ‘City Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 15 December 1924, p.4.