A tale of two headstones: part two, Sylvia McArthur, Balfour correspondent

The story of Balfour is told by two graves in a highland cemetery in north-western Tasmania. For more than a century, lying side by side, William Murray and Sylvia McArthur have been fixed silently in their interlocking roles in what historian Geoffrey Blainey called the ‘Indian summer’ of Tasmania’s first mining boom.

There is an interesting dynamic between these two people, who were interred on consecutive days in November 1912. William Murray was a 51-year-old husband and father of two, Sylvia McArthur a 15-year-old schoolgirl. He has Doric columns on his granite headstone, which is reputed to have been sent out from Scotland. She has a slab from J Dunn and Co, Launceston, and, as their graves suggest, they represented different social strata. As one of the owners of the principal mine, the Copper (Murrays’) Reward, William Murray was from the big end of town, living in what was once called ‘the mansion’. Sylvia McArthur was part of the globe-trotting fraternity of mine workers, the community that follows the speculators, grounded in the realities of remote mining towns a century ago, physical and cultural isolation, poor sanitation and health care. Sylvia would have lived in a corrugated iron hut, one of those described as looking like ‘opened out sardine cans’.[1] She is believed to have died of typhoid. William Murray died by putting a gun to his temple, reputedly because of financial and marital collapse stemming from the Copper Reward mine.[2] So, in different ways, they were both casualties of Balfour’s frenzied mining speculation.

Sylvia McArthur’s story begins with the marriage of William McArthur, one of nine children born to Scottish bounty immigrants, to Catherine Dolan, the daughter of Cygnet farmers.[3] They married in Zeehan, where he was a miner and she a housemaid.[4] Two of William’s brothers, Robert and John, likewise followed the mining profession wherever there was work.[5] At Zeehan in 1897 Catherine produced their second daughter, Sylvia Iris McArthur.[6] Emphatic endorsements of the Mount Lyell copper boom were then rising in Queenstown, Strahan and Zeehan. Built on a grand scale in 1898, Zeehan’s Gaiety Theatre and Grand Hotel had a stage larger than that of Hobart’s Theatre Royal and more seating than Hobart’s Town Hall.[7] Zeehan’s silver mines had also peaked, but the field was beset by shallow lodes and problems of ore treatment.

Catherine and William McArthur at Zeehan with their first three daughters, Florence, Sylvia and Gladys. Mora Studio, Zeehan, photo courtesy of Edie McArthur.

Tragically, in 1904 Catherine McArthur died after a short illness at the age of only 27, moving her husband to verse:

‘Tis hard to break the tender cord,

When love has bound the heart.

Tis hard, so hard, to speak the words:

We for a time must part.

Dearest love, we have laid thee

In the peaceful grave’s embrace,

But they memory will be cherished,

Till we see thy heavenly face’.[8]

By 1908, when William re-married, and with 20-year-old Marion May Delaney started adding boys to his four girls, Zeehan was in decline.[9]

The Balfour coach negotiating a sand dune. Photo by Fritz Noetling from the Tasmanian Mail, 9 March 1911, p.24.

The new boom town was Balfour. It was remote even by mining field standards, a shanty town lodged somewhere between Circular Head and the ‘true’ west coast. No road, railway or deep-water port served it. The Balfour coach could be bogged in beach sand or swamped by the Southern Ocean. Yet by the spring of 1909, investors were agog at the 1100 tons of ore, averaging about 30% copper, which the brothers William and Tom Murray had somehow dispatched to market. In October 1909 a report circulated that the Murrays had sold their Copper Reward mine for £50,000—a claim they denied.[10] The Balfour copper field was soon being hailed as a second Mount Lyell.[11]

By October 1911 William McArthur had secured the position of engine driver at the Copper Reward. It took his family a fortnight’s travel from Zeehan via Burnie and Stanley to join him at Balfour. Rough weather held up their voyage on the ketch HJH, forcing passengers ashore five kilometres from the Woolnorth stock station. Finally, a four-hour ride on the new horse-drawn Temma-Balfour tramway delivered the family to its remote new home.[12]

Balfour had already suffered the obligatory typhoid epidemic of the early life of a mining town by the time fourteen-year-old Sylvia McArthur arrived. The Circular Head Council apparently did not take much notice of this, because it afterwards suggested to the Balfour Advisory Board that it dump the town’s nightsoil in the Frankland River, presumably downstream of the local recreational area and fishing hole.[13] A sanitary inspector despatched to Balfour after the typhoid outbreak found only one unsanitary drain at the Balfour Hotel, plus the suspicion that a pig was being kept on that premises—apparently in anticipation of King George V’s coronation in June 1911, when it was patriotically sacrificed.[14]

William Murray was out of town at that time. Having taken an eighteen-year-old bride, the forty-eight-year-old was honeymooning in England.[15] In August 1911, when Hazel and baby Jean Murray saw Balfour for the first time, they took up residence in what one man called the ‘mansion’, perhaps the only house in town blueprinted by an architect.[16] Perhaps the Murrays also had acetylene lighting, which would have placed them ahead of the underground miners in the candle-lit Copper Reward.

The McArthur family and friends on the Frankland River bridge, with Sylvia at back (left) in the wide-brimmed hat. William McArthur photo from the Weekly Courier, 18 April 1912, p.17.

The same picnic party at the river. William McArthur photo from the Weekly Courier, 18 April 1912, p.17.

The McArthurs began to live their life in the social pages in January 1912, when Sylvia wrote her first letter to the Weekly Courier newspaper. It is through her words and her father’s photos that we get the story of everyday life in a remote settlement. Sylvia went from a very large school at Zeehan to a one-teacher operation of 23 students at Balfour. She stopped attending because there were no girls of her own age, and she felt as lonely at school as she was at home. Instead, she carried her father’s crib to the mine and looked after her younger siblings.[17] Her sisters became schoolteachers, and Sylvia’s own love of small children is very evident. For amusement she collected postcards and read copiously. The Christmas sports and picnic was the highlight of the social calendar. There was also a dance every few months to the tune of a piano accordion. Sylvia enjoyed the fern gullies and glades of the nearby Frankland River, a favourite picnic spot where walks were taken and the blackfishing was lively.[18]

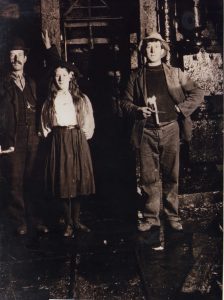

William and Sylvia McArthur pictured with an unknown man (right) underground in the Copper Reward. Photo courtesy of Edie McArthur.

One day she ventured underground at the Copper Reward. Her permanent interment underground was six months away when she looked to a future beyond the transitory mining town, one she would never know:

‘It was the first time I had been down a mine. I think it is a funny feeling one has whilst going down in a cage … Whilst I was down below a gentleman took a flashlight photograph of us. We all looked like ghosts, for our faces were so white. However, I would not like to leave Balfour without being able to say I was down a mine’.[19]

In her final letter to ‘Dame Durden’ of the Weekly Courier in October 1912, Sylvia described a concert given by the Balfour schoolchildren, illustrated, as usual, by her father’s pictures.[20] Her fatal illness may have been brewing even as the newspaper went to press.

What was William Murray’s condition? It must have been tempting for the Murrays to start living the good life that the speculation promised, and which could easily have landed them in debt. Perhaps the brothers had missed their big chance. It has been claimed that they refused an offer of £30,000 for the mine, a decision they may have come to regret.[21] William Murray shot himself in his home at Donald Street, Balfour, on 4 November 1912, reputedly as part of an unfulfilled double suicide pact with Tom.[22] Sylvia McArthur died in great pain next day ‘from a complication of complaints’ after a three-week illness.[23] She was buried overlooking the Frankland River that she loved. Her heartbroken father described the scene in the Weekly Courier:

‘For she’s sleeping on the hillside,

Where the morning sun will shine,

‘Mid a scene of ferns and dogwood,

Fringed with wild clematis vine,

With its tender fibres clinging,

Drawing close to the boughs above,

As our hearts are drawn to Sylvie,

By the tender cords of love.

And the fiercest storm in winter,

As it rages on the shore,

Will not disturb you, dearest Sylvie,

Where you sleep for evermore’.[24]

Ferns and dogwood still guard William Murray and Sylvia McArthur’s final resting-place. In fact the scrub has grown up so much that the cemetery’s river view has been lost. The ‘lonely spot near Balfour’, as William McArthur described it, is lonelier than ever.

[1] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 9 February 1910, p.3.

[2] See, for example, Heather Nimmo’s play ‘Murrays’ Reward: a play in two acts’.

[3] Thanks to Edie McArthur for help with McArthur family background. For Catherine Dolan, see birth registration no.1352/1877, Cygnet, to Thomas Dolan and Agnes Dolan, née Harrison.

[4] Marriage registration no.838/1895, Zeehan. Catherine gave her age as 18 but she was only 17; William was 28.

[5] Thanks to Edie McArthur for help with McArthur family background.

[6] She was born 16 October 1897, registration no.3194/1897, Zeehan.

[7] ‘Gaiety Theatre’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 November 1898, p.4.

[8] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 23 July 1904, p.2; memorial to Catherine McArthur, held by Edie McArthur.

[9] Marriage registration no.1389/1908, Zeehan.

[10] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 26 October, p.3; and 4 November 1911, p.2.

[11] ‘The far north-west’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 February 1911, p.2.

[12] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 11 January 1912, p.3.

[13] See ‘Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 21 December 1910, p.2; and 18 January 1911, p.3.

[14] For the pig suspicion and the unsanitary drain, see ‘Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 21 December 1910, p.2 and Circular Head Chronicle, 29 March 1911, p.2 respectively. For the pig slaughter, see the exchange of poems by JW Lord (‘Breheny’s pig’, Circular Head Chronicle, 21 June 1911, p.2 and 26 July 1911, p.4) and ‘Daybreak’ (Clement Lewis Gray), ‘RIP’, Circular Head Chronicle, 5 July 1911, p.3.

[15] ‘Social news’, Star (Sydney), 29 January 1910, p.16.

[16] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 9 February 1910, p.3; TB Moore diaries, 30 April 1912, ZM5641 (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery).

[17] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 13 June 1912, p.3.

[18] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young Folks’, Weekly Courier, 1 February 1912, p.3; 13 June 1912, p.3; 18 July 1912 p.3; 3 October 1912, p.3; Mavis McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young Folks’, Weekly Courier,18 July 1912, p.3.

[19] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 13 June 1912, p.3.

[20] Sylvia McArthur; in Dame Durden, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 3 October 1912, p.3.

[21] E Payne, ‘Balfour mine’, Examiner, 19 March 1951, p.2.

[22] The Circular Head Chronicle (‘Deaths at Balfour’, 6 November 1912, p.2) reported merely that Murray had ‘died suddenly’. The coroner found that Murray died of a self-inflicted ‘gunshot wound to the head … while of unsound mind’ (see SC195-1-82-13112, [TAHO]).

[23] She died 5 November 1912, registration no.652/1912, Montagu. See also ‘Deaths at Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 6 November 1912, p.2. The official record places her death 10 days later. No inquest was conducted.

[24] Poem by William McArthur published in Dame Durden, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 21 November 1912, p.3.