by Nic Haygarth | 21/03/19 | Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

They weren’t old lags, shifty safe-crackers or Hibernian highwaymen. They were Tasmanian highland snarers who flitted across the public record, leaving just their nicknames to tantalise the curious. ‘Five-fingered Tom’ was a little light fingered. ‘Black Harry’ was dark-skinned aberration in a white society. These traits help us to flesh out the legends of two early fur hunters who might otherwise have stayed as insubstantial as the Holy Ghost.

‘Five-fingered Tom’ Jeffries, photographed at the Hobart Penitentiary in 1873 by Thomas J Nevin. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

‘Five-fingered Tom’ was Thomas Jeffries. He was born as the second of three children to ex-convicts Thomas Jeffries and Ann Jeffries, née Willis, at Patersons Plains near Launceston in 1841.[1] His father was an illiterate labourer. Thomas Jeffries junior was born with an extra digit on his right hand (that is, five fingers and a thumb), hence ‘Five-fingered Tom’. This made him easily identifiable—good news for the cops! Jeffries regarded Evandale as his native place, but he was living and working on farms in the Sassafras area when in 1873 a warrant was issued for his arrest. The wanted man was described as about 35 years old, 5 feet 9 inches tall, with sandy hair, beard and moustache and a stout build, being ‘a good bushman [who] has spent much of his time hunting’.[2] First offender Jeffries was sentenced to eight years’ gaol for horse stealing. He spent four months making shoes in the Launceston Gaol, from which he vowed that he would abscond at the first opportunity—earning him a transfer to the Hobart Penitentiary.[3] What luck! Since Hobart prisoners were routinely photographed by Thomas J Nevin, we have the image of Jeffries attached to this article. He must have shucked off his bad attitude, since he served only five of his eight years.[4]

Like Jerry Aylett of Parkham, ‘Five-Finger Tom the Hunter’ moved into the high country by the 1880s, a time when Tasmanian brush possum had gained an export market.[5] Possum-skin rugs had been a useful earner for bushmen for decades but now the thicker highland furs had a reputation in the British Isles. In 1883 the ‘Tasmanian Opossum Tail Rug’ could be found alongside the ‘Grey Wolf Rug’, the ‘Silver Bear Rug’, the ‘Leopard, on Bear’ and the ‘Raccoon Tail Rug’ in the catalogue of Liverpool enterprise Frisby, Dyke and Co.[6] Lewis’s in Sheffield, Nottinghamshire, offered ‘real Tasmanian opossum capes’.[7] An 1887 ‘Rich winter fur’ auction in Dundee, Scotland, placed ‘Australian and Tasmanian Opossum’ alongside sealskin, sable, skunk, brown and polar bear, llama, leopard, puma, tiger and raccoon furs.[8]

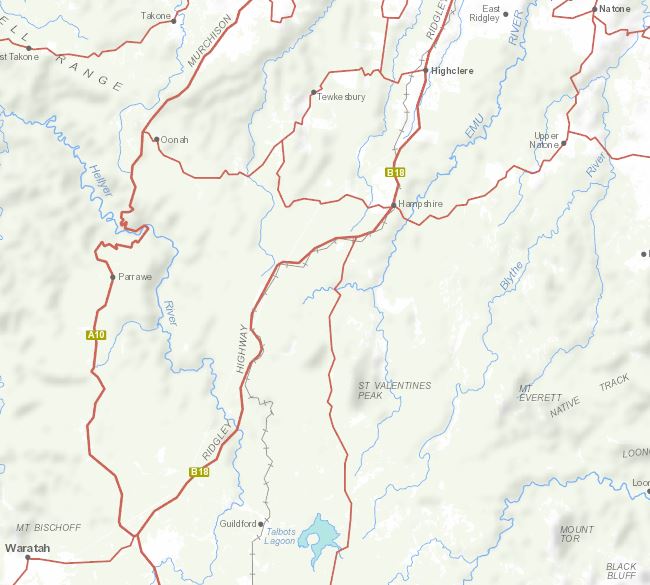

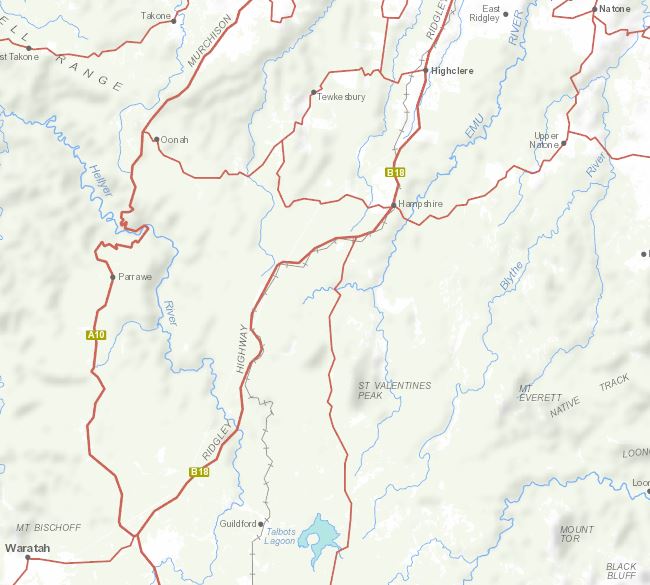

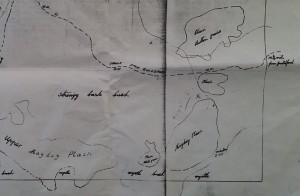

The Hampshire and Surrey Hills, Tasmania, map from the LIST database, courtesy of DPIPWE.

Waratah, a town born in the early 1870s at the Mount Bischoff tin mine, was a staging-post for both prospectors and hunters. We can follow Jeffries there in 1886 through the digitised pages of the Tasmania Police Gazette. He seems to have found it hard to stay out of trouble, allegedly committing an assault at Waratah before making for the hunting grounds of the Middlesex Plains.[9] Guildford Junction, a village created by the extension of the Emu Bay Railway to Zeehan in the late 1890s, was another hub for bushmen such as Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) timber splitters, hunters and prospectors. Jeffries and his mate Bill Todd were both based there in the period 1903–05, joining fellow hunters ‘Black Harry’ Williams, Tom Allen, the ‘Squire of Guildford’ Edward Brown and, from 1904, Luke Etchell.[10] They had a wide orbit. Todd, for example, was prospecting with George Sloane on the February Plains in 1901 when the latter discovered the body of lost Rosebery hotelier Thomas (TJ) Connolly.[11] Shopkeeper Allen packed stores into the Mayday gold mine under the Black Bluff Range in 1902.[12]

In the years 1888–1909 most of these men supplemented their income by claiming the £1 bounty on the head of the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger. Tom Allen appears to have received fifteen bounty payments—although, as a storekeeper and skins dealer, he may have submitted some applications on behalf of other hunters.[13]

Not so ‘Black Harry’ Williams, the so-called ‘colored king of the forest’, who probably claimed four tiger bounties.[14] He was a short, black-haired Afro-American bush farmer and hunter who arrived in Wynyard in 1887 aged about 24. After serving a month’s gaol for poaching neighbourhood ducks, Williams (‘A black man’!) started operating south of Wynyard (pre-1900), and later at Natone, Hampshire, Guildford and the Hatfield Plains (1900–08).[15] He caught two tigers at the Hampshire Hills in 1900, exhibiting a living one in Burnie. His intention was to sell it to Wirth’s Circus.[16] ‘Black Harry’ was reported to be submitting the other specimen, a very large dead one, for the thylacine bounty, although there is no record of this application.[17] Just enough details of his life survive with which to tell a story. In 1901 he was sued by Chinese storekeeper Jim Sing for failing to pay for a bag of carrots delivered to the Hampshire Hills; Williams counter-sued over Sing’s failure to pay for 100 wallaby skins delivered to Waratah by the hunter.[18] Three years later he was accused of breaking down a VDL Co stockyard at Romney Marsh near the Hatfield River in order to use the timber in a drying shed—making him an early adaptor of this technology (today Black Harry Road recalls his presence in this area). In 1905 Williams was described as the ‘champion trapper and bushman of the State’, the ideal man to lead a search for hunter Bert Hanson who went missing near Cradle Mountain.[19]

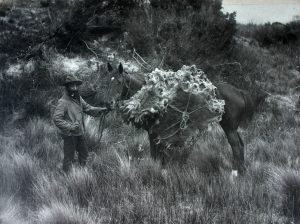

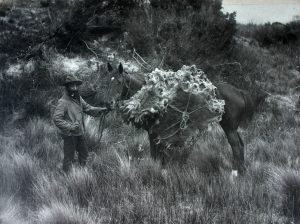

Wallaby hunter Henry Grave demonstrating his reliance on his horse as a pack animal, King Island, 1887. Photo by Archibald J Campbell, courtesy of Museums Victoria.

Jeffries may have been a contender for those honours. Knowledge of his hunting around Cradle Mountain with Todd—another man who flits across the public record—was passed down through generations of bushmen. Drawing on this oral record in 1936, Cradle Mountain Reserve Secretary Ronald Smith unwittingly fused the characters into Tom Todd, aka ‘Five-fingered Tom’. It was on the edge of the high plain they hunted, known as Todds Country, that Hanson died in a blizzard.[20] Correcting Smith’s article, another writer recalled that ‘Tom Jeffrey’ and his Arab pony Dolly were known for many years between Middlesex and Waratah, his mount being ‘the most faithful and gamest bit of horseflesh that ever packed a load over the Black Bluff’.[21] The winter haunts of the highland snarer were very cold, very wet and poorly charted, his comforts simple and meagre, his rewards contingent upon government regulation and global demand. Often he was unseen for months at a time. No newspaper trumpeted his story. Perhaps an extra digit and a different pigment were all that kept Jeffries and Williams from historical anonymity—but I hope there is a lot more to their stories that hasn’t yet been teased out.

[1] Thomas Jeffries senior, transported on the Georgiana, was granted permission to marry Ann Willis, transported on the New Grove, on 3 October 1838, p.88, CON52/1/1; Thomas Jeffries junior was born to Thomas and Ann Jeffries on 1 November 1841, birth record no.1848/1842, registered at Launceston, RGD32/1/3 (TAHO). He had elder and younger sisters: Mary Ann Jeffries, born 24 October 1839, birth record no.1021/1840, registered at Launceston, RGD32/1/3, address was given as Watery Plains; Maria Jeffries, born 11 June 1844, no.271/1844, registered at Launceston, RGD33/1/23 (TAHO).

[2] ‘Warrants issued, and now in this office’, Reports of Crime, 23 May 1873, vol.12, no.723, p.86.

[3] Prison record for Thomas Jeffries, image 25, p.11, CON94/1/2 (TAHO).

[4] ‘Prisoners discharged from Her Majesty’s gaols …’, Reports of Crime, 27 September 1878, vol.17, no.1001, p.157.

[5] See, for example, ‘Commercial’, Launceston Examiner, 24 November 1886, p.2; 19 April 1890, p.2. While William Turner failed to attract a reasonable price for Tasmanian brush possum from English buyers in 1871 (William Turner to the Colonial Treasurer, 27 September and 17 December 1872, TRE1/1/462 [TAHO]), in 1883 HE Button of Launceston began to ship furs to London: ‘Open fur season’, Mercury, 30 July 1926, p.3. For William ‘Jerry’ Aylett, see Nic Haygarth, ‘William Aylett: career bushman’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.28–55.

[6] Frisby, Dyke and Co advert, Liverpool Mercury, 12 November 1883, p.3.

[7] ‘Lewis’s great sale of mantels and furs’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 5 February 1886, p.1.

[8] ‘Sales by auction’, Dundee Courier and Argus, 19 November 1887, p.1.

[9] ‘Waratah’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 19 November 1886, vol.25, no.1426, p.187.

[10] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1903, p.56; 1904, p.412; 1905, p.61.

[11] ‘”Lost and perished in the snow”: another Cradle Mountain tragedy’, Advocate, 27 March 1936, p.11.

[12] Thomas Allen to James Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 28 January 1902, VDL22/1/33 (TAHO).

[13] Bounty no.374, 12 January 1899 (3 adults, ‘3 December’); no.401, 15 November 1900 (3 adults, ’15 June’); no.482, 21 January 1901 (3 adults, ’17 December’); no.22, 4 February 1901 (3 adults, ‘4 January’); no.985, 25 July 1902 (‘July’); no.1057, 27 August 1902 (’15 August’); no.1091, 17 September 1902 (‘4 September 1902’); no.462, 6 August 1903, (1 juvenile, ’24 July’), LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO). See ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 15 December 1900, p.2.

[14] ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 August 1905, p.2. The bounties were all under the name ‘H Williams’: no.344, 17 November 1899 (’10 October’); no.1078, 11 September 1902 (’31 July 1902’); no.1280, 2 December 1902; no.76, 20 February 1903 (’14 February 1903’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[15] Williams’ activities at Wynyard in 1887 and 1889 were recorded in the diaries of George Easton, held by Libby Mercer (Hobart). For his conviction on a larceny charge, see ‘Wynyard’, Colonist, 12 October 1889, p.2; and ‘Prisoners discharged …’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 8 November 1889, vol.28, no.1581, p.180. Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory listed H Williams as a hunter living at Wynyard in 1900 (p.223), 1901 (p.239) and 1902 (p.255). Yet he caught two tigers at the Hampshire Hills (Hampshire) in 1900. In June 1903 he advertised for sale a 50-acre farm on Moores Plain Road south of Wynyard (‘For sale’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 June 1903, p.3), and in the period 1903–08 he had a mortgage on a 98-acre block at Natone near Hampshire, which would have been a handy base for his hunting activities (Assessment rolls, Hobart Gazette, 8 December 1903, p.2080; 5 December 1905, p.1847; Tasmanian Government Gazette, 12 November 1907, p.1951; and 30 June 1908, p.739). Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory placed him at Guildford Junction in 1905 (p.61) and 1906 (p.61). ‘Veritas’ placed him at the Hatfield Plains south-east of Waratah in 1905 (‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’).

[16] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 November 1900, p.2.

[17] ‘Inland wires’, Examiner, 14 December 1900, p.7.

[18] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 18 October 1901, p.2.

[19] ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’.

[20] Ronald Smith, ‘Scene of hunter’s tragic death’, Mercury, 21 March 1936, p.9.

[21] ‘BEG’, ‘Cradle Mountain memories’, Advocate, 24 March 1936, p.6.

by Nic Haygarth | 20/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

Ever felt the need to turn the orthodox version of history on its head, and look at it upside down? Sometimes I want to write history from the ground up, from the perspective of people at the bottom of the food chain. With that in mind, I once set out to try to prove that the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) was primarily a fur farmer during its first century, that is, that more money was generated by the culling of marsupials on its land than by grazing and agriculture. Unfortunately, there are few surviving records of the skins sales of disparate hunter-stockmen employed by the company, making the task very difficult.

That the VDL Co learned to exploit the fur trade emphasises that the company’s survival for nearly 200 years has pivoted on its flexibility. When wool-growing failed, it withdrew, leased its lands and waited for the right time to return as a wool, dairy, beef, timber and brick producer. When it could find no minerals on its lands, it built a port and established a railway so that it could exploit other people’s mineral exports. It sold its land and its timber. When the fur trade peaked in the 1920s it exploited that. Now it is referred to as Australia’s biggest dairy farmer. Is high-end heritage tourism or Chinese niche tourism the next chapter in the story of Woolnorth, the VDL Co’s remaining property?

Just to rewind a little, the hunter-stockmen who worked the VDL Co’s land had always exploited the fur trade. It was part of their employment obligations: we pay you a small wage, thus giving you the incentive to increase your income by killing all the grass-eating marsupials and all potential predators (tigers, wild dogs and eagles) of sheep, and thereby conferring a mutual benefit. You sell the marsupial skins, and we will even throw in a bounty for every predator you kill.

The killing of predators represented a bonus for hunter-stockmen whose main game was killing wallabies, pademelons and possums. By 1830 thylacines were being blamed for killing the company’s sheep, although it is clear that poor pasture selection and wild dogs were bigger problems. After the catastrophic loss of 3674 sheep at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills in the years 1831–33 to severe weather conditions and the attacks of wild animals, it was decided to temporarily cease grazing sheep there, transferring that stock to Circular Head and Woolnorth.[1] In 1830 a £1 bounty was offered for the killing of a particular thylacine at Woolnorth.[2] From 1831 the VDL Co paid a regular reward for killing thylacines on its properties, initially 8 shillings, later 10.[3] The Court of Directors in London seemed to panic about the company’s prospects, stating that ‘We fear the hyenas and wild dogs, more than climate’.[4] The dilemma of the dog problem is clear. Requests for a thylacine-killing dog for Woolnorth were matched by reports of sheep depredations of dogs belonging to Woolnorth servants.[5] In 1835–37 the VDL Co employed a dedicated ‘pest controller’, James Lucas, to kill wild dogs and thylacines at first at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, then at Woolnorth.[6] Lucas, a ticket-of-leave convict, could be said to have been the first Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, although he was never referred to by that name and was employed there only briefly.[7] He operated on the same thylacine bounty of half a guinea. Whether due to Lucas’ performance or other influences, stock losses at Woolnorth dropped dramatically during his time there and the panic over thylacines and wild dogs subsided. However, bounty payments for the killing of predators had been resumed by 1850, as the following table illustrates:

Rewards paid by the VDL Co for the killing of predators at Woolnorth 1850–51

| Name |

Time |

Program |

Kill |

Payment |

| Edward Marsh |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena |

5 shillings |

| A Walker |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Two hyenas |

10 shillings |

| Richard Molds |

Aug 1850 |

Cross bred Leicester sheep |

Three dogs |

15 shillings[8] |

| A Walker |

Nov 1850 |

Improved sheep |

Hyena |

£1-2-11[9] |

| Richard Molds |

Feb 1851 |

Leicester sheep |

Dog |

5 shillings[10] |

| A Walker |

Sep 1851 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena & Two Eagle Hawks |

4 shillings 6d[11] |

| W Procter |

Dec 1851 |

Woolnorth |

Hyenas |

10 shillings[12] |

VDL Co withdrawal and the Field brothers on the Surrey Hills

In 1852 the VDL Co withdrew from Van Diemen’s Land, becoming an absentee landlord and, by 1858, its Hampshire and Surrey Hills and Middlesex Plains blocks were all leased to the Field family graziers. Tasmanian furs were already renowned, even before a market was found for them in London. Tasmanian bushmen and excursionists favoured possum-skin rugs as bedding. The best brush possum rugs to be had in Melbourne were reputedly those made by Tasmanian shepherds from snared skins, where the animals grew larger and more handsome than their Victorian counterparts.[13]

Fields’ outposted hunter-stockmen invariably hunted for meat, skins and clothing, burning off the surrounding scrub and grasslands to attract game. When an 1871 party visited the Hampshire Hills station, the peg-legged Jemmy, who was the designated cook, whipped up wallaby steaks. At the Surrey Hills, Charlie Drury, a delusional ex-convict hunter-stockman whom Fields inherited from the VDL Co, fed them cold beef, and the visitors got to try those famous possum-skin rugs, which, as was customary, were alive with fleas. While his guests battled these, Drury went ‘badger’ (wombat) hunting by the light of the moon with about a dozen kangaroo-dogs, bringing home three skins and one entire animal—presumably for breakfast. As he explained at the dining table, ‘the morning after I have been out badger-hunting at night I always eat two pounds of meat for breakfast, to make up for the waste created by want of sleep’. Travelling further, the party found that Jack Francis, stockman at Middlesex Plains, made his family’s boots and shoes from tanned hides. He also tanned brush possum skins for rugs, which again formed the bedding—flealessly this time.[14]

Records of hunter-stockman sales of skins from this period are scant. A rare example is an account in the VDL Co papers of its Mount Cameron West ‘tigerman’ William Forward sending 180 wallaby and 84 pademelon skins to market in April 1879.[15] In 1879 the open season for ‘kangaroo’ (wallaby) was from 31 January to 31 July, suggesting that Forward’s haul represented at most two months’ worth out of a six-month season.[16] By market prices of the time these skins would have been worth at least £8–4–0 and at most £14–14–0. If we assume that his haul for the six-month season was three times as much, we can imagine him earning at least as much as his annual wage of £20–£30. And that is without bonuses for thylacine killings.

Luke Etchell, career bushman

While Charlie Drury was drinking himself to death at his hunting hut on Knole Plain, and the VDL Co plotting the removal of Fields and all their wild cattle from the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, Luke Etchell was a child growing up fast. He was the son of John Etchell or Etchels, a transported ex-convict harking from rural Lancashire. How many of the sins of the father were visited on the son? By the time of his transportation at the age of fifteen, John Etchell had already racked up convictions for housebreaking, theft, assault and, perhaps most telling of all, vagrancy. He was illiterate.[17] While still a convict in Van Diemen’s Land, he twice saved someone from drowning. [18] However, the negative side of the ledger kept him in the convict system. Christopher Matthew Mark Luke Etchell—a child with most of the Gospels and more—was born to John and Mary Ann Etchell, née Galvin, at Stanley, on 17 December 1868, as perhaps their fourth child.[19] (The origins of Mary Ann Galvin or Galvan have so far proven elusive.[20]) His family lived in a hut at Brickmakers Bay which was destroyed by fire in 1874, then appears to have moved to Black River, at a time when payable tin had been found at Mount Bischoff and specks of gold in west- and north-flowing rivers.[21] John Etchell worked as a labourer, a paling splitter and a prospector who claimed to have found gold eighteen km south-east of Circular Head in 1878.[22]

Life was not harmonious or easy, however, as suggested by Mary Ann Etchell’s successful application for a protection order against her husband in August 1880. In the court proceedings she alleged that about a year earlier he had threatened to sell everything in order to raise money to get him to Melbourne, where she supposed he was now. For the last five months all he had contributed for the upkeep of his family was 228 lb (103 kg) of flour and one bag of potatoes. [23] It seems that the family never saw John Etchell again and, given the request for a protection order, they were probably glad about it.

Certainly Luke Etchell became self-reliant very quickly. He claimed that at the age of nine, that is, in 1877, he was already working in a tin mine on Mount Bischoff and at one of the stamper batteries at the Waratah Falls, and it is true that, almost in the Cornish tradition, young boys found mining work of this kind.[24] (One of his contemporaries as a bushman, William Aylett, born in 1863, claimed to have been learning how to dress tin at Bischoff at the age of thirteen in 1876.[25]) His English-born relative John Wesley Etchell was certainly established in Waratah by December 1878, operating a shop owned by the ubiquitous west coaster JJ Gaffney, and the family made the move there, presumably with John Wesley Etchell as the major breadwinner. [26] Luke, like some of his brothers and sisters, had at least one brush with the law in his youth.[27]

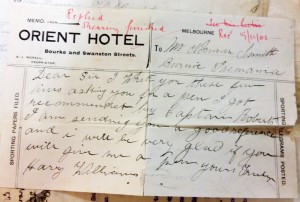

Even ‘Black’ Harry Williams the tiger killer needed to go shearing for additional income. Here he asks the VLD Co for a shearing pen in 1901. From VDL22-1-31 (TAHO).

Etchell was probably with his family at Waratah until at least 1886, when he was eighteen. Over the next two decades he became an expert bushman, apparently commanding familiarity with all the country between the lower Pieman River and Cradle Mountain.[28] His base was at Guildford Junction, the village centred on the junction of the VDL Co’s lines to Waratah and Zeehan, on the hunting territory of the Surrey Hills. He also became handy with his fists, featuring in a public boxing match in 1902.[29] Other hunters, successors to Drury, were working the Surrey and Hampshire Hills. By 1900 ‘Black’ Harry Williams, for example, the ‘colored [sic] king of the forest’, was building a reputation as a tiger tamer on the Hampshire Hills, even showing a live one in Burnie which he intended to sell to Wirth’s Circus.[30] Williams probably collected four government thylacine bounties, whereas Etchell collected only one, in 1903, most of his incidental tiger kills coming after the bounty was abolished.[31]

In 1910 ‘Tasmanian Chinchilla (clear blue Australian possum)’ took its place in the American fur catalogue alongside Hudson seal, skunk, beaver, wolf and chamois. Advert from the Chicago Daily Tribune, 17 December 1910, p.26

By 1905 Etchell was sufficiently well known as a bushman of the high country to be recommended as the man to lead a search for Bert Hanson, the seventeen-year-old lost in a blizzard on the eastern side of Dove Lake.[32] Making a living as a bushman meant grasping every opportunity that came along, be it splitting palings, cutting railway sleepers, taking a contract to build or repair a road or working an osmiridium claim. In 1910, for example, Etchell’s £30 tender for work on the road at Bunkers Hill was accepted by the Waratah Council.[33] In 1912 he obtained a tanner’s licence, suggesting that he intended to deal in skins.[34]

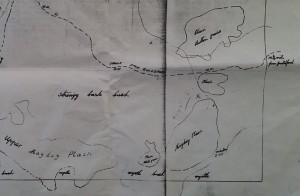

‘X’ marks the spot. The Etchell Mayday (First of May) Plain hut raided by police in 1937 in the south-western corner of the Surrey Hills block. Note also the prospectors’ camp marked nearby. From AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

However, it was as a snarer that Etchell made his reputation. He would have learned how to hunt as a boy from his father or brothers. Like the Ayletts, the Etchell family dealt extensively in the fur trade. Luke’s brother William snared and bought skins.[35] His cousin Harold Reuben Etchell had run-ins with the law over skin dealings, being the subject of a police stake-out and raid on a hut on the Mayday Plain (now First of May Plain).[36] Ernest James Etchell was another hunter who tested or blurred the hunting regulations.[37] However, Luke struck up a partnership with his brother Thomas, who also dabbled in prospecting.[38]

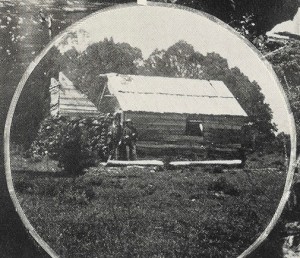

Atkinson’s hut and skin shed at Thompsons Park, on the Surrey Hills block. Thompsons Park was the site of a Field brothers’ stock hut. Later it also served seasonal hunters.

The pile of rubble or huge chimney butt beside Atkinson’s hut from a previous building on the Thompsons Park site.

As outlined previously, having hunters remove the plentiful game from its remaining land benefited the VDL Co stock—and the company gained doubly by charging these men for the privilege. The VDL Co engaged Surrey Hills hunters on a royalty system of one-sixth of their skins taken. In February 1912, for example, its Guildford man Edward Brown told its Tasmanian agent AK McGaw that Thomas Etchell had requested a run near the Fossey River, whereas R Brown wanted the 31 Mile or the West Down Plain (which turned out to be outside the Surrey Hills boundary). ‘I have told them that they must report to me before sending any of their skins away’, he wrote, ‘so I can count them and retain two out of every dozen for the company …’ [39] The disadvantage of this system for the VDL Co was that hunters could cheat, and later that season Brown claimed that DC Atkinson and Luke Etchell were not submitting all their skins to him from a lease Atkinson had taken on ‘the Park’. Brown found particular fault with their second load of skins:

‘The next lot was over 1½ cwt and Etchell gave me 11 which weighed 8 lbs and said “that was his share” but Atkinson would not give any as he caught them on his own ground. I know for sure he as [sic] snares set other than on his own ground. I think he was given the right on the conditions he gave 2 in the dozen regardless of where they were caught. Anyhow Atkinson should have given 11 and that would leave about ½ cwt to come off his own ground …’[40]

Ironically, the Animals and Birds Protection Act (1919) ushered in perhaps the greatest marsupial slaughter in Tasmanian history. In the open season winters from 1923 to 1928 about 4.5 million ringtail possum, brush possum wallaby and pademelon skins were registered.[41] It is easy to imagine why at some stage the VDL Co increased its royalty on the Surrey Hills from one-sixth of all skins taken to one-third. It sent men with pack-horses around the leased runs every fortnight to collect skins. Harry Reginald Paine described a raid by police and VDL Co officers on a Waratah house owned by Joe Fagan which the company believed contained skins obtained without royalty payment from the Surrey Hills block.[42] However, the late 1920s and early 1930s were dark days economically, with only the 1931 gold price spike and government incentives like the Aid to Mining Act (1927) giving hope to rural workers. Many prospectors went looking for gold in the Great Depression years, and some got into trouble. In 1932 Luke Etchell and Cummings of Guildford sought and found the Waratah prospector WA Betts, after he was lost in the snow for two weeks. After giving him a good feed, they returned him to Guildford on horseback.[43] Again, Etchell was the man to whom people looked when someone went missing in the high country.

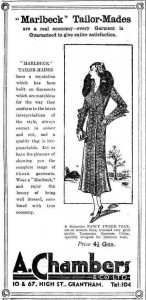

The fashionable British bride would not think of departing on her honeymoon without her Tasmanian brush possum collar coat in 1932. Advert from the Grantham Journal, 29 October 1932, p.4.

The open season of 1934, in which nearly a million-and-a-half ringtails were taken in Tasmania, was a godsend to the VDL Co which, during an unprofitable year for farming, made £500 out of hunting.[44] Thomas Etchell may not have been too wide of the mark when it predicted that an open season would benefit the community to the extent of £300,000–£400,000.[45] Did it benefit the possum population? The downside of that record-breaking season for hunters was that it was followed by two closed seasons while ringtail numbers recovered.

By the mid-1930s Luke Etchell was stockman for the shorthorn herds of RC Field’s Western Highlands Pty Ltd, which existed at least 1932‒38, and a regular correspondent with the police on hunting matters.[46] Ahead of the open season in 1937, for example, he advised Waratah’s Constable MY Donovan that ‘the Kangaroo and Wallaby were that numerous that they were eating the grass off and leaving the sheep and cattle on the runs short’.[47] Later that year, with the thylacine finally part protected and the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board keen to find living ones, Etchell was the ‘go to man’ for the Surrey Hills, Middlesex Plains, Vale of Belvoir and the upper Pieman. He suggested the hut in the Vale of Belvoir as a good base for the search.[48] He told Summers that ‘some years ago he has caught six or seven Native Tigers during a hunting season but for many years now he has not seen or caught any, proving that they have become extinct in this part, or driven further back’.[49]

Hut in the Vale of Belvoir. AW Lord photo from the Weekly Courier, 20 July 1922, p.22.

Benefiting from Etchell’s advice, and using Thompsons Park on the Surrey Hills block as another base, the government party, consisting of Sergeant MA Summers, Trooper Higgs, Roy Marthick from Circular Head and Dave Wilson, the VDL Co’s manager at Ridgley, scoured the region near Mount Tor, around the head waters of the Leven, the Vale of Belvoir and the Vale River down to its junction with the Fury and the Devils Ravine without finding signs of thylacine activity. A further search was conducted around the Pieman River goldfield and the coast north-west of there.[50] After commenting on the large numbers of brush possums in the area searched, Summers arranged for Etchell to secure seven pairs of black possums for the Healesville Sanctuary, Victoria.[51] Again, in 1941, Etchell advised that on the Surrey Hills, ‘the kangaroo and wallaby are plentiful … and that open season would be beneficial for everyone.[52]

There were bumper hunting seasons near the end of World War II and after it, with £15,000-worth of skins sold at the sale at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, more than 32,000 skins offered there in 1944 and record prices being paid at Guildford in 1946.[53] One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins for sale in 1943.[54] Taking advantage of high demand, in 1943 the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue—these included Painter Run (Painter Plain), Park Run (Old Park?), Mayday Run (Mayday Plain, now First of May Plain, in the furthest south-east corner of the Surrey Hills block), Talbots Run (presumably near Talbots Lagoon), Peak Run (Peak Plain), Black Marsh Run (probably near the site of the old Burghley Station), and those which probably corresponded to the mileposts on the Emu Bay Railway, the 25 Mile, 36 Mile and 46 Mile Runs. Like the traditional Cornish ‘tribute’ mining system, by which parties of men competed to work particular sections of a mine, the highest bid won the contract for each run. Men paying as much as £70 for seasonal rental of a run felt short-changed when heavy snowfalls curtailed their activities, which were still subject to the official hunting season. Nearly all the men who hunted the Surrey Hills block in 1943 combined this work with pulp wood cutting for Australian Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) at Burnie, or another job in the timber industry. Waratah’s Trooper Billing estimated that pulp wood cutting averaged seven hours per day, compared to 16 hours per day for snaring.[55] Billing regarded the Surrey Hills block as a game-breeding ground which damaged the interests of adjacent landholders.[56]

Luke Etchell posing before the Guildford skin sale in 1946. Winter photo from the Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

These bumper seasons were the end of the road for the Etchell brothers. Thomas Etchell died in September 1944.[57] Brother Luke was still snaring at 78 years of age in 1946, when the Burnie photographer Winter posed him in best suit, that apparently being the outfit of choice for hauling your skins on your shoulder to the Guildford sale.[58] Luke Etchell died in Hobart on 8 June 1948.[59] There were a few good hunting season after that, but in 1953 new regulations curbed an industry already reduced by weakening European and North American demand for skins. The era of the hunter-stockman and the professional bushman—the man who could live by his nous in the bush—was drawing to a close.

[1] ‘Van Diemen’s Land Company’, Hobart Town Courier, 25 September 1835, p.4.

[2] Edward Curr to Joseph Fossey, Woolnorth manager, 12 May 1830, VDL23/3 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [henceforth TAHO]).

[3] Edward Curr to James Reeves, Woolnorth manager, 2 April 1831, VDL23/4 (TAHO).

[4] Court of Directors to JH Hutchinson, Inward Despatch no.98, 10 October 1833, VDL193/3 (TAHO).

[5] See Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 8 February 1836, 30 June 1836, 10 August 1836, 14 September 1836 and 1 February 1837, VDL23/7 (TAHO).

[6] Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 6 March 1835, VDL23/6 (TAHO).

[7] For an overview of James Lucas’ work for the VDL Co, see Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000.

[8] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[9] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[10] VDL232/1/5, p.215 (TAHO).

[11] VDL232/1/5, p.255 (TAHO).

[12] VDL232/1/5, p.272 (TAHO).

[13] HW Wheelwright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[14] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

[15] James Wilson to James Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Notices to correspondents’, Launceston Examiner, 26 November 1879, p. 2; ‘Kangaroo hunting’, Cornwall Chronicle, 31 January 1879, p. 2.

[17] John Etchell was tried at the Derby Assizes 15 May 1843 for housebreaking, stealing money and assault, see CON33/1/53. http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-53,308,90,F,60 accessed 18 December 2016.

[18] Matthias Gaunt, ‘Indulgence’, Launceston Examiner, 1 December 1849, p.4.

[19] Birth registration 702/1869, Horton.

[20] Luke’s mother, Mary Ann Etchell, died at Waratah in 1903 (‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 October 1903, p.2).

[21] See file (SC195-1-57-7410, p.1) at https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=john&qu=etchell# accessed 18 December 2016.

[22] ‘Mining intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 28 September 1878, p.2. See also Charles Sprent’s dismissal of John Etchell’s alleged tin discovery at Brickmakers Bay in 1873 (Charles Sprent to James Norton Smith, 6 July 1873, VDL22/1/4 [TAHO]).

[23] ‘Stanley’, Mercury, 12 August 1880, p.3.

[24] ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.

[25] See Nic Haygarth, ‘William Aylett: career bushman’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.28–55.

[26] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 26 February 1880, p.4.

[27] Luke and Flora Etchell were convicted of stealing potatoes at Black River in 1883 (‘Emu Bay’, Reports of Crime, 20 April 1883, p.61; ‘Miscellaneous information’, Reports of Crime, 4 May 1883, p.70). Luke’s sister Sarah Ann was convicted of concealing the birth of a still-born child in pathetic circumstances in Waratah (‘Supreme Court’, Daily Telegraph, 22 August 1884, p.3). The most serious matter was his brother Thomas Etchell’s conviction of indecent assault in Waratah (‘Supreme Court, Launceston’, Mercury, 19 February 1896, p.3).

[28] ‘The Corinna fatality’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 November 1900, p.4.

[29] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 July 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 November 1900, p.2; ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 August 1905, p.2. In December 1900 Williams exhibited the skin of a tiger said to be seven feet long in Burnie (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 December 1900, p.2). For another Williams tiger story, see ‘Inland wires’, Examiner, 14 December 1900, p.7.

[31] Potential Williams bounties: no.344, 17 November 1899 (’10 October’); no.1078, 11 September 1902 (’31 July 1902’); no.1280, 2 December 1902; no.76, 20 February 1903 (’14 February 1903’), (’17 March 1902’). Etchell bounty: 25 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[32] J North, ‘A Waratah man’s opinion’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[33] ‘Local government: Waratah’, Daily Telegraph, 9 March 1910, p.7.

[34] ‘Tanner’s licences’, Police Gazette, 9 August 1912, p.183.

[35] For snaring see, for example, Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 16 July 1911, VDL22/1/47 (TAHO). For buying see for example, ‘Alleged illegal buying of skins’, Advocate, 27 July 1939, p.2.

[36] For the police raid, see Sergeant Butler to Superintendent Grant, 10 May 1937, AA612/1/12 (TAHO). See also ‘Trappers defrauded’, Mercury, 3 September 1930, p.9; and ‘Conspiracy charge’, Mercury, 4 September 1930, p.10. In 1943 police interviewed Harold Reuben Etchell in Wynyard but failed to find any illegally obtained skins (Detective Sergeant Gibbons to Superintendent Hill, 14 September 1943, AA612/1/12 [TAHO]).

[37] ‘Sheffield’, Advocate, 21 September 1937, p.6.

[38] See HS Allen to AK McGaw, 25 October 1907, VDL22/1/39 (TAHO). Thomas Etchell went osmiridium mining in 1919 during the peak period on the western field (see Pollard to the Attorney-General’s Department, 19 November 1919, p.113, HB Selby & Co file 64–2–20 [Noel Butlin Archive, Canberra]).

[39] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 20 February 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[40] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 27 June 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[41] Police Department, Report for 1925–26 to 1927–28, Parliamentary paper 41/1928, Appendix J, p.13.

[42] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, the author, Somerset, Tas, 1992, pp.47–48.

[43] ‘Owes his life to dog’, Advocate, 13 July 1932, p.8; ‘Lost in snow for fortnight’, Advocate, 27 June 1932, p.4.

[44] VDL Co annual report 1934, Miscellaneous Printed Matter 1880‒1967, VDL334/1/1 (TAHO).

[45] T Etchells [sic], ‘Open season for game’, Examiner, 5 May 1934, p.11.

[46] ‘Personalities at the show’, Examiner, 7 October 1936, p.6. Ironically, one of his tasks now was to keep other hunters off the company’s land (see, for example, advert, Advocate, 18 January 1834, p.7) in case they endangered stock or let stock out through an open gate.

[47] MY Donovan to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, 12 January 1937, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[48] MA Summers’ report, 3 April 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[49] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[50] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[51] ‘Opossums for Melbourne’, Advocate, 26 May 1938, p.6.

[52] Luke Etchell, ‘The game season’, Advocate, 15 May 1941, p.5.

[53] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4; ‘Over 32,000 skins offered at sale’, Advocate, 13 September 1944, p.5; ‘Record prices at Guildford skin sale’, Advocate, 30 July 1946, p.6.

[54] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4.

[55] Trooper Billing to Superintendent Hill, Burnie Police, 14 August 1943, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[56] Trooper Billing to Superintendent Hill, Burnie Police, 14 August 1943, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[57] ‘Thanks’, Advocate, 26 September 1944, p.2.

[58] ‘Still trapping at 79’, Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

[59] ‘Deaths’, Advocate, 12 June 1948, p.2; ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.