When I was a Tasmanian child the school-ma’amish Mrs Marsh demonstrated the mastery held by Colgate toothpaste over a piece of chalk. Or something. ‘It gets in?’, chirped this harridan’s childhood charges, as she pulled the chalk from a bottle of red dye and snapped it in half. Sure enough, the red dye had suffused the chalk. Apparently it did get in.

Quite what this had to do with the whitening powers of toothpaste was and is beyond me, but I still thought of her when, abandoning the TV, I gazed at Black Bluff gleaming on the skyline. If ever a mountain had the Colgate ring of confidence it was this one. Its winter coat seemed brighter, thicker and longer-lasting than those of Mount Roland and Western Bluff. Of the peaks I saw regularly during the course of my north-west-coastal school days only Mount Ironstone, behind Deloraine, rivalled it as a snow-cone.

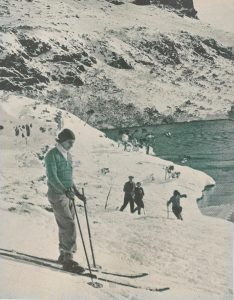

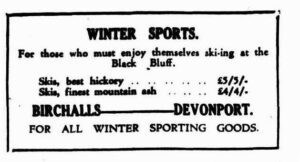

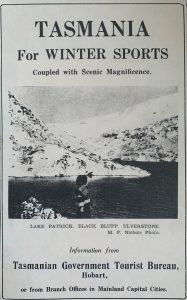

So I wasn’t surprised to learn that, in the late 1920s and 1930s, when Tasmanians began to attack their peaks on homemade skis and toboggans, Black Bluff came in for some serious scrutiny. In the winter of 1928 Ulverstone jeweller and photographer George (GP) Taylor and Cradle Mountain Reserve Board Secretary Ron Smith climbed the bluff to test its suitability for winter sports. ‘In frosty weather after a fall of snow’, they wrote, ‘skiing and tobogganing could be carried on successfully, and the accessibility of the mountain from the coast should make it a popular winter resort, provided sufficient accommodation is available on the mountain’.[1]

The Ulverstone Tourist and Progress Association had surveyed a Black Bluff track from near Taylor’s Loongana shack Levenvale, but on the back of this report the Public Works Department’s Paddy Doyle cut a better one (the Brookes Track) which opened in January 1930.[2] Further afield near Cradle Mountain, Waldheim Chalet tourism operator Gustav Weindorfer must have noted events at Black Bluff apprehensively. For years he had been encouraging the development of hiking and winter sports at Cradle Mountain with modest return. Both were starting to take off now, but a new mountain playground at Black Bluff—a place you could park your car under—might scotch his business.

Photos courtesy of the late Jack Breheny.

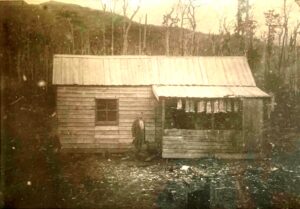

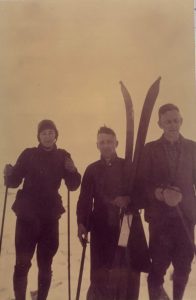

As it turned out, Weindorfer was in his grave by the time Ulverstone enthusiasts pressed the issue of forming a ski club.[3] The club took its cues from the Legges-Tor-based Northern Tasmanian Alpine Club (NTAC), dubbing itself the North West Alpine Club. The club’s first outing was in June 1932, when a delegation from the NTAC consisting of Jack Branagan, Reg Hall, Bill Mitchell and Eileen Perrin visited Black Bluff in tandem with about 50 local members.[4] Taylor’s two-room Levenvale, 90 minutes by car from Ulverstone, seemed an ideal base camp, with skiers relaxing by its roaring fire and in its bunks. Even veteran skier ET Emmett threatened to test the new ski field.[5] As was the case at Cradle Mountain, conditions were not often optimal for skiing, but another successful outing was staged on 6 August 1933.

In 1935 an enlarged club rode ‘a wave of enthusiasm and activity’.[6] Some of that was directed at changing the club’s name to the Black Bluff Ski Club and erecting a twelve-bunk ski chalet at a spot below Paddys Lake known as Boozers Rest.[7] Benefiting from a £15 Tourism Department grant, club members split timber and hauled it up to the 950-metre mark, and during the winter and spring of 1935 working bees soon completed the two-room hut with spacious fireplace.[8]

This, surely, would bind members socially just as the NTAC had bonded over chalet building. Skiers now had a refuge from the weather and, conveniently, skis and toboggans could be left on the mountain. What could possibly go wrong?

A few things. World War Two (1939–45) played a part in the club’s fortunes. While Hobart and Launceston were no closer to their ski fields than Ulverstone, they had bigger population bases to draw upon in the event of the original enthusiasts petering out, moving on or mobilising as part of the war effort. However, something else preceded that. In winter with snow on the ground and ice on the lake it was probably hard to imagine a bushfire roaring down on the chalet, but that is exactly what happened in mid-summer, January 1939. The building was destroyed. The ‘boozers’ lost their roost.[9] There was no impetus to rebuild even in the post-war period when nature sports and studies boomed. Now you can drive to a ski field—why climb?

Mrs Marsh probably knew nothing of climate change, and the effect it had on toothpaste … or snowfall. Unreliable snowfalls are the bugbear of skiers, but in my child’s eye Black Bluff still has its pearlies out, beckoning those bright young things who knew how to Charleston and how to wear a sou’wester.

[1] GP Taylor and RE Smith, ‘Black Bluff Mountain: winter sports and mountaineering near Ulverstone’, 21 August 1928, report to the Tasmanian Government Tourist Bureau.

[2] ‘Ulverstone: Black Bluff Track opened’, Examiner, 28 January 1930, p.5.

[3] ‘NW Tasmanian Alpine Club’, Australian and New Zealand ski year book, New South Wales Ski Council, Sydney, 1933, p.228.

[4] ‘Mountain sports’, Mercury, 29 June 1932, p.5.

[5] ‘Winter sports: visitors to Tasmania’, Mercury, 22 July 1932, p.6.

[6] ‘Black Bluff Ski Club’, Australian and New Zealand ski year book, New South Wales Ski Council, Sydney, 1935, p.234.

[7] ‘North West Alpine Club’, Advocate, 22 May 1935, p.6; ‘Ski club hut’, Advocate, 25 May 1935, p.6.

[8] ‘Ulverstone’, Advocate, 27 June 1935, p.6; ’Black Bluff hut’, Advocate, 17 July 1935, p.6; ‘Trip to Black Bluff’, Advocate, 3 September 1935, p.6.

[9] GP Taylor, ‘Bush fires’, Advocate, 30 January 1939, p.6.