by Nic Haygarth | 10/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history

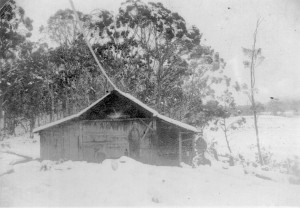

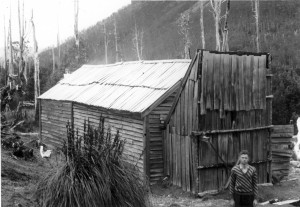

The diversion tunnel at Mayne’s tin mine, a later development near the Orient Tin Mine.

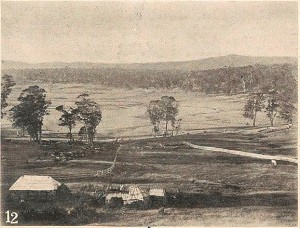

The view of Mount Agnew from the Orient Tin Mine site, where the first west coast church and reading room stood in 1883.

In 1902 you could get a tertiary education at Zeehan, a place dominated by frogs, snakes and marsupials a dozen years earlier. The Zeehan School of Mines was affiliated with the University of Tasmania, putting it on equal academic footing. The university issued the school’s diplomas and certificates, and appointed its examiners. Subjects studied at Zeehan could be counted towards a degree from the University of Tasmania.[1]

Yet the first educational institute on the west coast was established nearly two decades earlier. It stood on the claim of the Orient Tin Mine at Cumberland Creek, near Trial Harbour. Strictly speaking, it was a Methodist church—the first church on the mining fields south of Waratah.

Travelling journalist Theophilus Jones described the site when he accompanied the Minister for Lands, Nicholas Brown, on a visit to the Heemskirk tin field in May 1883. The Orient Tin Mine was then considered the premier mine in the district. Such impressive assay values had been obtained here that the future of the Heemskirk tin field seemed assured. Anticipation was then building about the first crushing at the Orient, which would follow soon after.

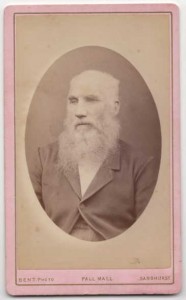

Thomas Stephens Williams, manager of the Orient Tin Mine, photo courtesy of Mr Barnard.

On arrival at the mine, Minister Brown, who happened to be the chairman of directors of the Orient Tin Mining Company, was ushered into Cornish mine manager Thomas Williams’ (c1826‒1901) ‘snug little’ cottage. Here the Devon-born Fanny Williams served home-made cake and tea. The new church, built by Williams and his sons Luke and Tom from sawn timber, with a split shingle roof, and a blackwood interior adorned with chandeliers, had recently been opened with a traditional Wesleyan Methodist tea meeting. Fanny Williams and other mining folk had provided sandwiches, sponge cakes and blanc manges for the occasion.[2] (Later, a collection of books would be obtained and, with Luke Williams acting as the librarian, during week days the church would act as a reading room, like a tiny mechanics’ institute.[3]) The machinery was also impressive. A Robey And Co steam engine imported from England had been installed as an auxiliary to the waterwheel which would drive the 10-head stamper battery. Five Munday’s self-emptying concave buddles were ready for tin separation.[4] Nearby was another Cornish legacy, a grave with a picket fence which represented the final resting place of the wife of the original Orient mining manager, John Williams.[5]

The surprise failure of the Orient crushing in October 1883 threw ‘a great damper … on lode tin mining at Mount Heemskirk …’[6] Confidence in the field evaporated. Thomas Williams resigned his post, and the little church and reading room was removed. Mayne’s Tin Mine later produced 140 tons of metallic tin near the site of the Orient, showing that the area had at least limited potential.[7]

Two of Williams’ sons later followed in his footsteps. Richard Williams (c1866–1919) managed the Colebrook Mine on the west coast of Tasmania, then copper mines at Chillagoe and Cloncurry in Queensland, the Byron Reef Gold Mine in Victoria before dying at Southern Cross, Western Australia.[8] Former Orient librarian Luke Williams (c1859‒1931) became a well-known Tasmanian mine manager, operating, among others, the Mount Read Mine and the Chester Mine. The village of Williamsford was named in his honour.[9] He had a long association with Robert Sticht, general manager for the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company.

Luke Williams was innovative. Under his management, in the winter of 1917, the Copper Reward Mine at Balfour switched from raising copper underground to raising tin from the button-grassed surface. The button-grass was burnt and the land ploughed by horse-team. The loose earth was then scooped into a sluicing race, down which a horse drew a ‘puddling harrow’ (sluicing fork) to break down lumps and reduce the material to a pulp. Two dams built from button-grass sods cemented together by clay supplied a hydraulic sluicing operation which worked the lower face of the tin-bearing ground. Operations ceased when the price of tin dropped in 1921.[10] Williams died in comfortable retirement in Hobart a decade later as a well-known pig breeder and orchardist, his early efforts to enlighten the west coast having been long forgotten.[11]

[1] Patrick Howard, The Zeehan El Dorado, Mount Heemskirk Books, Blackmans Bay, 2006, pp.186‒87.

[2] ‘Our Special Reporter’ (Theophilus Jones), ‘The west coast tin mines’, Mercury, 28 May 1883, p.3;

[3] (Theophilus Jones), ‘West coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 December 1896, p.1; Luke Williams, ‘The Orient Library, Heemskirk’, Mercury, 27 September 1883, p.3.

[4] Gustav Thureau, Report on the present condition of the western mining districts, Parliamentary Paper 89/1884, p.1.

[5] (Theophilus Jones), ‘West coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 December 1896, p.1. She died in June 1882 (‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 14 June 1882, p.3).

[6] Editorial review of 1883, Launceston Examiner, 1 January 1884, p.2.

[7] AH Blissett, Geological Survey explanatory report, One Mile Geological Map Series, Zeehan, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1962, p.106.

[8] ‘About people’, Examiner, 1 October 1919, p.6.

[9] Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk mines and mining’, Examiner, 27 February 1928, p.5.

[10] ‘Balfour notes’, Circular Head Chronicle, 16 February 1921, p.3.

[11] ‘Mr Luke Williams’, Advocate, 29 July 1931, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 09/12/16 | Circular Head history, Tasmanian high country history

Henry Thom Sing, from the Weekly Courier, 30 May 1912, p.22.

A downtown Launceston store is the face of a forgotten immigrant success story. The building at 127 St John Street was commissioned by Ah Sin, aka Henry Thom Sing or Tom Ah Sing, Chinese gold digger, shopkeeper, interpreter and entrepreneur. He was born at Canton, China on 14 March 1844, arriving in Tasmania on the ship Tamar in 1868.[1] Sing appears to have come from to Tasmania from the Victorian goldfields, and he was quick to seize on this experience when the northern Tasmanian alluvial goldfields of Nine Mile Springs (Lefroy), Back Creek and Brandy Creek (Beaconsfield) opened up. Like Launceston’s Peters, Barnard & Co, who hired Chinese miners through Kong Meng & Co in Melbourne, Sing began to recruit Chinese diggers on the Victorian goldfields.[2] His good English skills were an asset in trade and communication, and throughout his time in Launceston his services were drawn upon regularly as an interpreter in court cases involving Chinese speakers as far afield as Wynyard and Beaconsfield.

Circular Head farmer Skelton Emmett had been washing specks of gold in the Arthur River for years before a minor rush was sparked by two sets of brothers, Robert and David Cooper Kay, and Michael and Patrick Harvey, in April 1872.[3] Within three months, 160 miner’s rights had been issued and 70 claims registered.[4]

Claims were spread over about 2 km around the confluence of the Arthur and Hellyer Rivers. The European diggers generally preferred to work ‘beaches’ in the river.[5] Two European claims, the Golden Crown and the Golden Eagle, were on the Arthur downstream of the junction. The Golden Eagle party, who included William Jones and John Durant, strung a suspension bridge consisting of a single two-inch rope across the river in order to work both banks and for easy access: effectively it was a ‘bosun’s chair’ or flying fox. They worked their claim with a sluice box and Californian pump.[6] James West and party’s claim known as the Southern Cross was in a small gully on the southern side of the Arthur. The Kays’ claim was ‘in the gulch of a ravine’ a little further inland from the river. The claim of Frank Long, who later found fame on the Zeehan–Dundas silver field, was further down the same gulch.[7] The British Lion claim of W King was at the junction of the Arthur and the Hellyer, the Harvey brothers’ claim on the Arthur above it.[8] Waters from Circular Head and a man named House also held claims.[9]

Most of the gold obtained in the area by Chinese came from working the sand bars and shallows of the Arthur River. Sing had several roles on the field. Although Seberberg & Co had also engaged Chinese diggers for Tasmania, the 50 or so Chinese at the Arthur appear to have represented only two agents, Sing and Peters, Barnard & Co, both Launceston based.[10] Because he had a Launceston business to maintain, Sing’s time at the diggings would have been limited. He appears to have had two claims which were worked by Chinese parties, and he acted as an interpreter for other parties.[11] He also bought gold from diggers.[12] In November 1872, with the river low enough to permit an attack on its dry bed, both Sing parties engaged in ‘paddocking’, that is, diverting part of or the entire stream by damming it on their claim. On the upper claim the resulting wash dirt was put through a cradle, but the eight men expected to achieve better results when their sluice boxes were complete. Likewise, Lee Hung was building a sluice box.[13] The upper party once took 10 oz of gold in a day.[14] Wha Sing’s claim on the Arthur above the confluence included a vegetable garden, which would have provided his party with both food and cash, since stores would have been at a premium on the isolated field.[15]

One of the Chinese parties was said to have ‘turned’ the Arthur River in order to work its bed. While the Arthur is a large river, this is not as difficult an undertaking as it sounds. The idea is to drive a short tunnel or channel through a hairpin bend in the river, diverting its flow. A quick scan of the map makes it obvious where this could have been done. In fact the diversion channel would not have been on the Arthur River, but on the Hellyer, just above its junction with the parent river. This ingenious method of exposing a stream bed was employed on many gold fields and in Tasmania by osmiridium miners on Nineteen Mile Creek and other places.

The largest nugget obtained by February 1873―1 oz 3½ dwts―was found by a Chinese party in the river, but, generally, bigger nuggets were taken in the creeks.[16] Frank Long claimed to have got his best gold about 10 km from the Arthur River, and his was ‘much more nuggety’ than that of James West, who worked closer to the river. The gold appears to have been patchy. All the productive claims were above that of the Kays.[17] Working the creeks was harder in summer, but diggers made up for the lack of sluicing water by using chutes to bring the washdirt to the river.[18]

The Arthur River gold field was deserted by the end of 1873, and the Chinese soon switched to alluvial tin mining in the north-east. Sing built up his Launceston business. By the time he was naturalised as a British subject in 1882, he was renting a shop and residence at 127 St John Street, Launceston.[19] In 1883 he bought the site and erected a new premises designed by Leslie Corrie.[20] Here he sold imported Chinese groceries, ‘fancy goods’, preserved fruits, silk, tobacco, fireworks and the Chinese drinks and remedies Engape, Noo Too and Back Too.[21] Sing’s residence also served as a staging-post of Chinese tin miners arriving in Launceston. In 1885 he cemented his position in the north-east by buying out the store of Ma Mon Chin & Co at Weldborough, which afterwards operated as Tom Sing & Co.[22]

While a £10 poll tax was levied on Chinese entering the colony in 1887, Launceston’s established Chinese population became part of the community, with local businessmen Chin Kit, James Ah Catt and Henry Thom Sing supporting the work of the Launceston City and Suburbs Improvement Association by staging spectacular Chinese carnivals at City Park in 1890 and the Cataract Gorge in 1891. Fire gutted the Sing premises in 1895, and as a result it was either altered or rebuilt to the design of Launceston architect Alfred Luttrell.[23] This building remains today.

Sing married twice, and fathered at least seven children.[24] Both his brides appear to have been European. His death, in May 1912, aged 68, after 44 years in the Launceston business community, passed almost without comment in the Tasmanian press, perhaps indicating that, despite his naturalisation, a racial barrier between Chinese and Europeans remained.[25] Probate valued at £1738 suggested modest success.[26] Like the former Chung Gon store in Brisbane Street, today Henry Thom Sing’s St John Street store remains part of Launceston’s commercial sector.

[1] Naturalisation application, 22 July 1882, CSD13/1/53/850 (TAHO), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=tom&qu=sing, accessed 10 December 2016.

[2] ‘New Chinese diggers’, Tasmanian, 11 February 1871, p.11.

[3] ‘Gold discoveries at King’s Island and Rocky Cape’, Cornwall Chronicle, 29 April 1872, p.3.

[4] Charles Sprent to James Smith from Table Cape, 21 July 1872, NS234/3/1/25 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

[5] ‘The Hellyer goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicle, 22 November 1872, p.2.

[6] ‘Notes on the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 20 December 1872, p.2.

[7] ‘A look round the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 3 February 1873, p.2.

[8] ‘Notes on the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 20 December 1872, p.2.

[9] ‘The Hellyer gold-field’, Cornwall Chronicle, 16 December 1872, supplement, p.1.

[10] ‘The Nine Mile Springs goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicle, 13 May 1872, p.2; ‘Chinese immigration’, Tasmanian, 18 May 1872, p.8.

[11] See, for example, ‘More gold from the Hellyer diggings’, Tasmanian, 25 January 1873, p.12.

[12] ‘Table Cape’, Tasmanian, 25 January 1873, p.5.

[13] ‘The Chinese diggers at the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 November 1872, p.3.

[14] ‘The Hellyer goldfield’, Cornwall Chronicl,e 22 November 1872, p.2.

[15] ‘The Chinese diggers at the Hellyer’, Cornwall Chronicle, 6 November 1872, p.3.

[16] ‘The Hellyer diggings’, Mercury, 13 February 1873, p.3.

[17] ‘Table Cape’, Cornwall Chronicle, 17 January 1873, p.3.

[18] SB Emmett, ‘The western gold field’, Launceston Examiner, 1 February 1873, p.3.

[19] Naturalisation application, 22 July 1882, CSD13/1/53/850 (TAHO), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=tom&qu=sing, accessed 10 December 2016.

[20] ‘Tenders’, Launceston Examiner, 26 July 1884, p.1..

[21] ‘Law Courts’, Tasmanian, 26 May 1883, p.563.

[22] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 19 September 1885, p.1.

[23] ‘Tenders’, Launceston Examiner, 7 March 1895, p.1.

[24] ‘Deaths’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1882, p.2; marriage registration no.966/1884, https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=henry&qu=thom&qu=sing#; accessed 10 December 2016.

[25] ‘Deaths’, Weekly Courier, 30 May 1912, p.25.

[26] Will AD96/1/11, LINC Tasmania website, accessed 10 December 2016.

by Nic Haygarth | 27/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

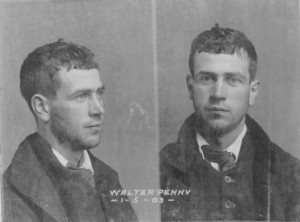

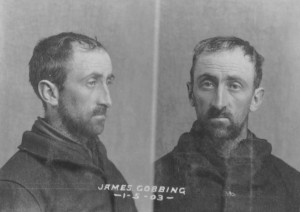

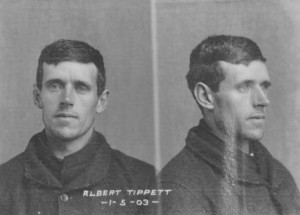

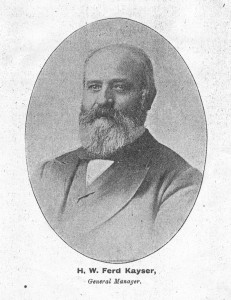

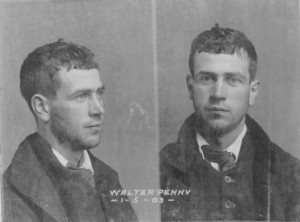

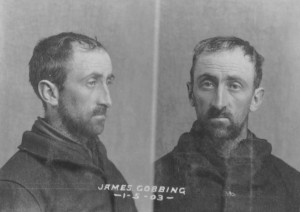

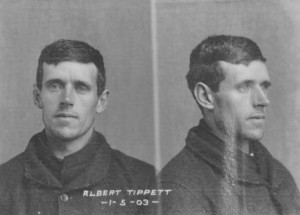

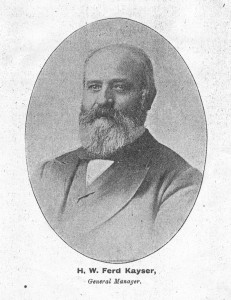

In 1903 three Waratah men—Walter Penney, James Cobbing and Albert Tippett—were gaoled for five years for receiving tin stolen from the Mount Bischoff Company. Yet the court case looked more like a showdown than a trial—the culmination of a 25-year feud between Ferd Kayser and his Cornish detractors. The three accused men worked the Waratah Alluvial plant on the Waratah River, which recovered tin lost into the water by the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds. They claimed that the tin they were accused of stealing had simply been retrieved from the bottom of the Waratah Alluvial dam on the river. The prosecution case was that the tin had been stolen directly from the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds earlier when Penney, Cobbing and Tippett worked there. At the dock, Kayser, the Mount Bischoff Co’s high profile general manager slugged it out with the canny Cornish tin dresser Richard Mitchell. Their on-going argument was ostensibly about the better ore processing method—German or Cornish. Yet in truth it was more about ego, reputation and the struggle to make a living.

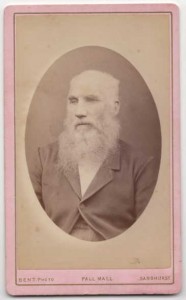

Mount Bischoff mine manager Ferd Kayser. Photo from the Australian Mining Standard, 1898.

The defence case rested on being able to show that the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds and its own tin recovery plants on the Waratah River were ineffectual, and that Mount Bischoff Co staff who had identified the stolen tin as being theirs were incapable of doing so. In speaking for the defence, Mitchell attacked Kayser’s ‘antiquated’ dressing machinery, claiming that his own plant (he was manager of the Anchor tin mine in the north-east) was ’50 years ahead of it’.[1] Laughably, Kayser failed to even identify Mount Bischoff Co dressed tin when it was placed in his hand at the dock. For five years he had been living away from the mine in Launceston as general manager, allowing John Millen to run the mine. Perhaps he was so out of touch that he had forgotten the appearance of the dressed tin he had produced for 23 years.

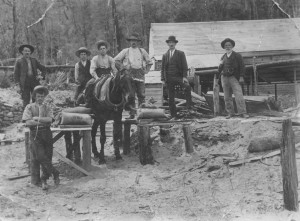

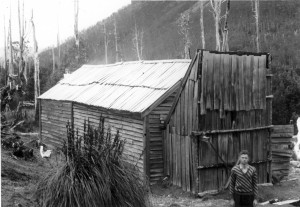

A succession of Cornish miners had been nipping at his heels throughout that time. Cornish miners asserted their superiority as hard-rock miners, exploiting their Cornish ethnicity as an economic strategy.[2] Being Cornish was their ‘brand’. Cornish miners were famous for their instinctive, canny style of management. They grew up mining from childhood, learning their craft on the job, without a formal mining education.[3] At Mount Bischoff Cornishmen they had tried to enhance this reputation by operating small retrieval plants, ‘lifting the crumbs from the rich man’s table’, that is, they had realised that the richest material on their leases was not lode tin or alluvial tin but escaped Mount Bischoff Co ore. The first to recognise this was the Waratah Tin Mining Company (Waratah Tin Co). Tailings from the Mount Bischoff Co sluice boxes emptied into a creek which ran through the Waratah Tin Co property into the Waratah River. In about 1878 that company’s Cornish tin dresser, Richard Mitchell, switched from working its tin lode to extracting ore from the creek.[4] Other Cornish tin dressers—ASR Osborne, William White and Anthony Roberts—followed suit. Their plants, the East Bischoff Company, Bischoff Tin Streaming Company, Bischoff Alluvial Tin Mining Company/Phoenix Alluvial Company and Waratah Alluvial Company, bore nicknames that suggested they were ‘shearing’ the Waratah River—the ‘Catch ‘em by the Wool’, ‘Shear ‘em’, ‘Shave ‘em’, ‘Hold ‘em’ and the ‘Catch ‘em by the Wool no. 2’ respectively.

Cornish tin miner Anthony Roberts (right) operating a later tin mine, Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, in the North Bischoff Valley. Photo courtesy of Colin Roberts.

To many, Cornwall was a byword for simplicity, economy and improvisation. However, to Kayser, a champion of technology, Cornwall, the so-called ‘cradle of the Industrial Revolution’, was a ‘Luddite’. Antiquated Cornish mining methods were his favourite hobbyhorse. One of his first actions on taking over the management in 1875 was to sack the Mount Bischoff Co’s Cornish ore dresser Stephen Eddy, whose improvised appliances, he said, included ‘the hand-jigger and all the old primitive appliances his great grandfather used’.[5]

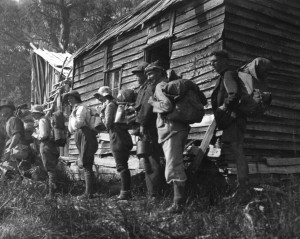

The Ringtail Sheds, in the period 1907-09, with the new power station below them at left. Stephen Hooker photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

However, Kayser could not deny that there was plenty of ore for the Cornish tin dressers to retrieve. It has been estimated that the Mount Bischoff Co dressing sheds alone lost 22,000 tons of metallic tin into the Arthur River system up to 1907—30,000 tons by 1928. To put that in perspective, the Mount Bischoff Co produced about 56,000 tons of metallic tin, meaning that about one-third of the tin ore mined at Mount Bischoff ended up not in smelted bars for shipment to London, but in the Arthur River system. After deriding his Cornish rivals for years, in 1883 Kayser established the first of two tin recovery plants of his own on the Waratah River. The Ringtail Sheds at the base of the Ringtail Falls on the Waratah River stood on the old Waratah Tin Co block, where Richard Mitchell had set up the very first tin recovery operation five years earlier. Well-graded access tracks to the Ringtail Sheds were constructed from both sides of the Waratah River, the track on the western side being used to pack the ore out from the sheds.[6] These formed a loop by meeting at a foot bridge across the river just above Ringtail Falls, the site of the sheds. They are still used today to visit the Mount Bischoff Co Power Station which was afterwards built below the sheds. However, so much tin remained in the Arthur River system that in the 1970s the idea was entertained of dredging not just the river but coastal deposits outside the river mouth.[7]

(The mugshots above are from GD63-1-3, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.)

[1] ‘Alleged theft of tin ore’, Daily Telegraph, 22 April 1903, p.8.

[2] Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, Cornwall Limited Editions, Fowey, Cornwall, 2004 (originally published 1996), p. 234; Ronald M James, ‘Defining the group: nineteenth-century Cornish on the North American mining frontier’, in Cornish studies: Two (ed. Philip Payton), University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 1994, cited by Philip Payton, Cornwall: a history, p.234.

[3] Geoffrey Blainey, The rush that never ended: a history of Australian mining, Melbourne University Press, 1978 (first published 1963), p.244.

[4] HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, no. IV, 1892, pp.350–51.

[5] HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, p.346.

[6] ‘Alleged theft of tin ore’, Daily Telegraph, 21 April 1903, p .4.

[7] ‘Tin worth $45 million in Arthur River’, Advocate, 10 May 1973, p. 1.

by Nic Haygarth | 27/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

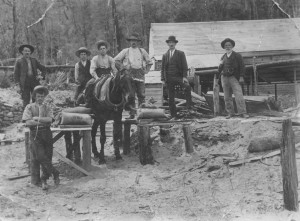

Clem Penney (right) and friends, Waratah, 1924. Probably a JH Robinson photo. From the Weekly Courier, 17 January 1924, p.26.

In 1924 seeing a thylacine was a rare event for most people. A few lingered in zoos. Tasmanian hunters like Luke Etchell occasionally took one in a necker snare set for wallabies, but their numbers were so few that the state government bounty scheme had long since been abandoned. The money was in living specimens. James Harrison, the Wynyard marsupial wrangler, offered a very useful £25 for a live tiger for supply to zoos.[1] When WJ Mullins captured a live mother and cubs they were such a novelty that he turned them into an exhibit doing the rounds of the agricultural shows—and Burnie’s New Year’s Day Sports, where amateur naturalist Ron Smith saw them. He recorded in a letter:

‘The young ones were nearly as big as full grown rabbits; two of them were sucking for all they were worth, and the other was asleep. The mother was about as big as an ordinary collie, but slenderer. Large brown eyes, and the face in front of the eyes narrower than a dog’s. Fur more like a possum’s than a dog’s. Altogether a very pretty animal’.[2]

On the very same day as Smith’s caged encounter, Clem Penney met a tiger family in the wild. Sixteen-year-old Penny, born and bred in Waratah, was in the North Bischoff Valley near the Arthur River when he heard a muffled bark. Turning quickly, he saw a two thylacines—a large male, and a small, young female—advancing towards him.

A few thylacines had been seen in this area over the years by miners. However, Penney’s tiger tale, told by a third party, seems somewhat exaggerated. It is unlikely that Penney, as was suggested, carried an automatic pistol simply out of fear of meeting tigers. Certainly it was normal for a man in a rural area to carry a firearm, and young Penney produced his and took a shot at the leading animal. When the pistol failed to discharge, he had time to reach for a tree limb—suggesting that the thylacine advance was far from menacing. This was a pair of animals with their young, which they were probably defending. ‘Grasping this excellent club’, Penney’s chronicler wrote,

‘he stood on guard. The female tiger was in the lead and was crawling forward. When about 6ft away she sprang full at him. He met her fairly with a sweep of his heavy club, knocking her backwards on to the ground, and followed up with a killing assault on her neck. Straightening himself instantly, the bushman found the male in the air from a mighty leap. Again the trusty club proved true, and the tiger was knocked to the ground. Gathering himself up, the animal dashed into the scrub on three legs, a foreleg being apparently broken, whimpering like a wounded dog.’[3]

How easy it was to destroy a family unit of what would be recognised belatedly as a critically endangered species.

Penney family, Waratah, Tasmania, mid-1920s, with thylacine killer Clem Penney far right at back, and his stripy doormat in the foreground. JH Robinson photo courtesy of Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

Penney returned home to Waratah with the carcass of the small female, which he displayed for the camera—probably that of the Weekly Courier’s regular contributor, JH (Jackie) Robinson. What happened to it after that? Another Robinson photo—of a Penney family group—seems to answer that question. While some thylacines skins were used as rugs, it looks like Clem Penney clubbed himself a stripy doormat.

[1] ‘Wanted’, Advocate, 19 June 1920, p. 5.

[2] Ron Smith to Gustav Weindorfer, 5 January 1924, p.132, LMSS150/1/1 (TAHO, Launceston).

[3] ‘A Waratah Resident’, ‘Fight with native tigers’, Weekly Courier, 17 January 1924, p.46.

by Nic Haygarth | 13/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

In May 1914 Ron Smith’s former Forth mate Ted Adams invited him to go hiking at Lake St Clair. Smith, who would be one of the major figures in the establishment of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park, could not make the appointed time.[1] He had business to attend to at Cradle Valley, but perhaps when that was done a cross-country short-cut would bring them together. ‘I thought … I could go overland to Lake St Clair to meet you there’, he told Adams.[2] It was perhaps in that instant that Ron Smith conceived the idea of the Overland Track between Cradle Valley and Lake St Clair. Ironically, it would take him another 27 years to walk it.

The opportunity finally came in late December 1940. Now fifty-nine years old and an invalid pensioner as the result of World War I service, Smith was also the secretary of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board, a land owner at Cradle Mountain and the major documenter of the area’s European history, flora and fauna. The Overland Track, the southern section of which was roughly marked by Bert Nichols in 1931, had only become suitable for independent travellers in 1935–36 after additional track and hut work by Nichols, Lionel Connell and his sons.[3] Few people had then taken up the challenge of tramping a track that now attracts about 10,000 per year from all over the world.

Ron’s early trips from his home at Forth to Cradle Mountain were accomplished on bicycle and on foot, with stopovers at Middlesex Station, but in 1940 he was able to drive from his new home at Launceston to Waldheim Chalet, Cradle Valley, in less than five hours. From 1925 to 1936 the Smiths had had their own house at Cradle Valley, and they would have one again, Mount Kate house, from 1947.[4] However, in 1940 they were content to stay in the late Gustav Weindorfer’s Waldheim Chalet, then managed by Lionel and Maggie Connell. In fact it was almost a second home for the Smith family, since Ron’s oldest son, whom he called Ronny, and Kitty Connell, daughter of Lionel and Maggie, were courting. And yet, despite the stringencies imposed by the war raging in in Europe, people continued to enjoy the major holiday period of the year. On Christmas Day 1940 Waldheim was bursting at the seams with hikers, 50 guests in all. What a peaceful Christmas for head chef Maggie Connell! Ron slept on a sofa in the dining room, his sixteen-year-old son Charlie on the floor of the same room.

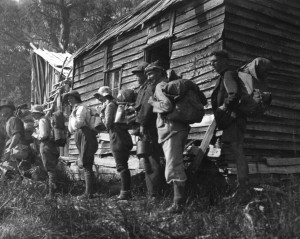

Ron Smith was always a formidable record keeper, and in his diary he recorded with typical precision that he and Charlie were on their way at 7.38 next morning, each of their knapsacks weighing 40 lbs (18 kg). After regular bouts of illness, Ron possibly doubted his own endurance. Two fit young men, Wally Connell and Ronny Smith, carried those heavy packs up to Kitchen Hut, sparing the hikers the full rigours of the tough climb up the Horse Track. After breakfast, Ron and Charlie continued alone, being passed by a party of five women who had started from Waldheim after them. Kitchen Hut was then only a three-sided shelter. There was no proper hut between Waldheim and Lake Windermere, making day one of an Overland Track trip a long and potentially dangerous one. Ron and Charlie reached Waterfall Valley before meeting their first fellow hikers—two young Sydney men—walking in the opposite direction (from Lake St Clair to Cradle Mountain, now prohibited).

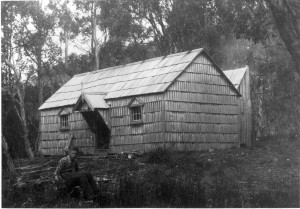

The old miners’ hut at Lake Windermere, 27 December 1940. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

A Fred Smithies shot showing the rest of the old Windermere Hut, taken during an Overland Track tramp. Courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

Father and son reached the Connells’ new Windermere Hut at 4.23 pm, nearly nine hours after setting out from Waldheim. The party of five women camped outside, leaving the hut to the men—and two grey possums, which entered, in what became Windermere tradition, via the chimney in their quest for food. Next morning, Ron and Charlie visited the c1901 Windermere miners’ hut, now in ‘great disrepair; the chimney fallen down and the roof very leaky’. Ron had reached the old hut with Gustav Weindorfer in 1911 and 1914; it was the furthest south he had so far travelled on the route of what became the Overland Track.[5]

Day two, from Windermere along the watershed of the Forth and the Pieman, then around the Forth Gorge and through to Pelion Plain, was another tiring one. They boiled the billy for lunch on the edge of the forest at Pine Forest Moor, with the dolerite ‘organ pipes’ of Mount Pelion West looming large ahead of them. At New Pelion Hut they re-joined the party of five women, greeted a married couple called Calver who arrived from Lake St Clair, plus four Victorian men who were returning to Waldheim after climbing Mount Ossa. There were ten in the Connells’ new hut, which had two rooms so that men and women could be separated. For Ron every new meeting was noteworthy. Names and sometimes addresses were exchanged, and it was a chance to chat and learn. The leisurely experience was far removed from that of more recent times, when the two-way traffic could make the Overland Track feel rather like a scenic Hume Highway.

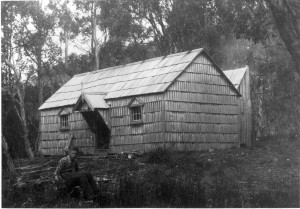

Flourishes of Federation Queen Anne and Arts and Crafts architecture in the Connells’ King Billy pine shingle New Pelion Hut, 28 December 1940, Charles Smith in the foreground. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

With rain threatening, the Smiths decided to spend a day close to shelter at Pelion. Ron had now ventured further south than his departed friend, Gustav Weindorfer, who had taken the census at the Pelion copper mine and climbed Mount Pelion West in April 1921.[6] The mine manager’s hut (Old Pelion) and the workers’ hut from that period were both in good repair. Leaving these huts, Ron and Charlie crossed Douglas Creek and followed the southern edge of Lake Ayr until they met the Mole Creek (Innes) Track near the rock cairns and poles marking the then Cradle Mountain Reserve’s eastern boundary.

Tommy McCoy’s hunting hut near Lake Ayr. Photo courtesy of the McCoy family.

McCoy’s hut as it looked in 1951, with Mount Oakleigh and Lake Ayr for a backdrop. Photo courtesy of the McCoy family.

The reserve had been a bird and animal sanctuary since 1927. Yet, cheekily poised about 250 metres beyond the boundary, Tommy McCoy’s new hardwood paling hunting hut made his intentions clear. Hobart hikers would become conservation activists, puncturing McCoy’s food tins with a geological pick, when they came across his hut in 1948.[7] However, the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary, a former possum shooter and a man of a different ilk, was much more respectful, leaving payment of threepence for a candle he removed from McCoy’s camp. Ron and Charlie also inspected the old post-and-rail stockyard near the western end of Lake Ayr on their way back to New Pelion. On their second night at Pelion propriety was dispensed with, as the Smiths and Calvers shared a room, leaving the other room for newcomers.

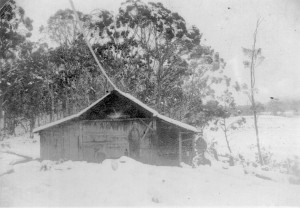

An unsympathetically cropped image of the two-room Du Cane Hut, 29 December 1940, with Cathedral Mountain omitted but Charles Smith in the foreground. Ron Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

An earlier Ray McClinton or Fred Smithies shot of the original one-room Du Cane, taking full advantage of the view of Cathedral Mountain.

The party of five women motored past the Smiths on the climb up to Pelion Gap next day, marching right through to Narcissus Hut, a distance of about 27 km in a day. Ron and Charlie took a leisurely pace, visiting Kia Ora Falls and camping at Du Cane Hut (Windsor Castle or Cathedral Farm), Paddy Hartnett’s old haunt, which had been converted to a two-room building in keeping with New Pelion. Reflecting, perhaps, his reduced stamina, Ron elected to wait on the main track while Charlie viewed Hartnett Falls. The pair also made a diversion to Nichols Hut, the walkers’ hut Bert Nichols had erected beside his old hunting hut. For a man who in his younger days rarely left a bush setting or bush person unsnapped, Ron Smith was relatively parsimonious with his photos on this trip, neglecting these buildings, McCoy’s hut and the old Mount Pelion Mines NL huts. He appears to have been ignorant of the other hunters’ huts located near the track between Pelion Plain and Narcissus River.

Ron and Charlie were accompanied most of the way from Pelion to Narcissus Hut by the Robinsons, a Sydney couple they had first met at Waldheim. Crossing the suspension bridge over the Narcissus River, Mrs Robinson’s hat landed in the drink and disappeared, despite a group rescue effort. Narcissus Hut, the staging post for the motorboat trip down Lake St Clair, as it is today, replicated the situation at Waldheim, being full to the brim and beyond, with numerous tents being pitched outside. Among the hikers were the economist and statistician, Lyndhurst Giblin, and HR Hutchinson, Chairman of the National Park Board, the subsidiary of the Scenery Preservation Board which oversaw the Lake St Clair Reserve. Indeed, it must have seemed like the veritable busman’s holiday when the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary met the Lake St Clair Reserve Board chairman on the Overland Track that united their realms.

Bert Fergusson’s motorboat loading at Narcissus Landing, 31 December 1940. Seventeen to board, including the party of five women, and a tentative Charles Smith (fourth from right). Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The trip was concluded in six days. It took 1 hour 45 minutes to traverse Lake St Clair in the famous Bert ‘Fergy’ Fergusson motorboat on New Year’s Eve, 1940. This seems extraordinarily slow progress—didn’t Paddy Hartnett row the lake faster than that 30 years earlier, against the wind?— until you realise how overloaded Fergy’s vessel was! Seventeen people were crammed aboard what was certainly not Miss Velocity. Ron and Charlie slept in Hut Twelve of Fergy’s tourist camp at Cynthia Bay, where a housekeeper, Mrs Payne, was also employed. From here Fergy operated a free ‘bus’ service (Jessie Luckman called it a ‘frightful old half bus’ sporting sawn-off kitchen chairs with basket-work seats) to Derwent Bridge, where the departing tourist joined one of Grey’s buses. The Lake St Clair tourist infrastructure of 76 years ago was surprisingly well organised. Charlie having departed with family members, Ron stayed on a day more and caught a bus back to Launceston via Rainbow Chalet at Great Lake and Deloraine, using a short stopover in that town to submit a butcher’s order for Fergy. All this recreational transport at a time when petrol was rationed for the war effort!

On 3 January 1941 Ron Smith rested at home, having at last completed the journey contemplated 27 years earlier. Perhaps the experience strengthened his belief in the need for a motor road from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair, thereby conferring universal reserve access.[8] Age may not have wearied him, but maybe at that moment his swollen right foot felt more comfortable on an accelerator than in a heavy boot.[9]

[1] See ‘Ron Smith: bushwalker and national park promoter’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.132–59.

[2] Ron Smith to GES Adams, 15 May 1914, NS234/17/1/4 (TAHO).

[3] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men, pp.122–27.

[4] See ‘Smith huts’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.36–43.

[5] For the 1911 trip, see Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 29 November and 1 December 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO). The pair’s arrival at the Windermere Hut in 1914 had scared the life out of its incumbent, miner/hunter Mick Rose, who feared he had been he had been nabbed engaging in out-of-season snaring.

[6] Gustav Weindorfer diary, NS234/27/1/8 (TAHO); ‘Mountain beauties: Tasmania’s charms’, Examiner, 6 January 1934, p.11.

[7] Interview with Jessie Luckman.

[8] See, for example, minutes of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board meeting, 25 June 1947, AA595/1/2 (TAHO).

[9] This account of Ron and Charlie Smith’s walk on the Overland Track is derived from Ron Smith’s diary, NS234/16/1/41 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 11/11/16 | Tasmanian high country history

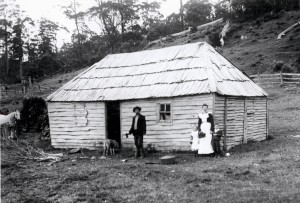

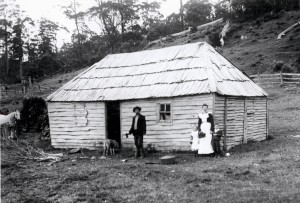

In Historic Tasmanian mountain huts, written with Simon Cubit, I told the story of a visit made to the Browns’ hut at Middlesex Station by the Anglican Bishop of Tasmania, Henry Hutchinson Montgomery and the Vicar of Sheffield, JS Roper, in February 1901.[1] Montgomery’s photo of the Brown family at their hut, featuring an eighteen-year-old Linda Brown with already two children, and the family turned out in Sunday best for the camera, tells us much about their isolated lifestyle, their social expectations and their pride.

Henry Montgomery’s photo of Field stockman Jacky Brown and his wife Linda Brown at their hut, with children Mollie (the babe in arms) and William (standing with his father). The girl standing beside Linda is possibly from the Aylett family and fulfilling the role of maid. PH30-1-3836 (TAHO).

The underlying story in this photo is the decline of the Field grazing empire, which was becoming as rickety as the Middlesex hut. That empire had been established by ex-convict William Field senior (1774–1837) and his four sons William (1816–90), Thomas (1817–81), John (1821–1900) and Charles (1826–57). The death of John Field of Calstock, near Deloraine, in the previous year had closed those generations which had spread half-wild cattle from the Norfolk Plains/Longford area as far as Waratah, intimidating other graziers and dominating its impoverished landlord, the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co). The Fields were notorious for occupation by default, and they knew that legitimately occupying the VDL Co properties of the Middlesex Plains and the Hampshire and Surrey Hills would also allow them to occupy all the open plains of the north-western highlands gratis. The Fields’ power over the VDL Co increased as the company’s fortunes declined. In 1840 the Field brothers leased the 10,000-acre Middlesex from the VDL Co for 14 years at £400 per annum.[2] In 1860, after financial losses forced the VDL Co to retreat to England as an absentee landlord, they obtained a lease of the Hampshire and Surrey Hills plus Middlesex—170,000 acres in all—for the same price, £400.[3] The problem for the VDL Co was that few other graziers wanted such a large, isolated holding, and that any who did dare to take it on would have to first remove the Fields’ wild cattle. In 1888 the Fields screwed the VDL Co down further to £350 for the lot for the first two years of a seven-year lease, raising the price to £400 for the final five years.[4]

Nor were any of these negotiations straightforward. With every lease there was a battle to collect the rent, necessitating letters between the respective solicitors, Ritchie and Parker for the VDL Co, and Douglas and Collins for the Fields. Thomas or John Field would stall, demanding a reduction in rent for fencing, rates or police tax. On one occasion they requested the right to seek minerals, and to make roads and tramways on the leased land—and to take timber for the construction of this infrastructure.[5] Worse yet, in 1871 some of Fields’ wild cattle from the Hampshire or Surrey Hills got confused with VDL Co stock and ended up on the Woolnorth property at Cape Grim, and the VDL Co couldn’t figure out how to get rid of them.[6] Since Fields would soon ask to rent Woolnorth—and be refused—it was as if their advance guard had infiltrated the property ahead of a storming of the battlements.[7] The VDL Co’s solicitor told them that to shoot the offending animals would be to risk a Field law suit, leaving the company no option but to buy them from Fields and then weed them out for slaughter.[8]

However, now things were changing. By the 1890s reduced meat prices and natural attrition had taken their toll on the Field empire. John Field was the only one of the four brothers still standing. The VDL Co was now fielding offers from potential buyers of the large Surrey Hills block, as the company looked to land sales and timber for financial redemption. John Field’s final gesture in 1900 was to offer the VDL Co £75 per year for Middlesex.[9] The VDL Co wanted £125, and in the new year of 1901 the executors of John Field’s estate haggled for a concession. They wanted their landlord to offset some of the increased rental by paying for improvements to the station. ‘The place is greatly out of repair and the house would require to be a new one throughout’, WL Field told VDL Co local agent James Norton Smith. ‘The outbuildings are none and there is not a fence on the place’.[10]

We can see for ourselves that some of this, at least, was true. The unfenced, out-of-repair Middlesex ‘house’ in Montgomery’s photo had already undergone renovations, a chimney having been removed from its eastern end. However, Field was probably exaggerating a little. Perhaps there were no outbuildings, but Fields probably always kept a second hut at Middlesex for the stockmen who came up for the muster.

Silence spoke for the VDL Co. Receiving no reply to his request, WL Field agreed to the annual rental of £125 for seven years, with an option of seven years more at £150 per annum, noting that ‘we have the 10,000 acres of govt land adjoining it at a rental of £60 and I consider the block as good as the co’s and it will save a lot of fencing having both …’.[11]

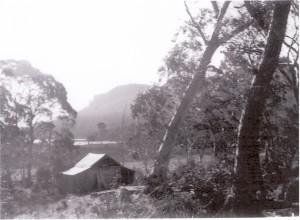

The Middlesex Station huts in February 1905, with Jacky, Linda Brown and two children standing in front of the second (mustering) hut. The hut occupied by the family can be seen at the extreme left in the left-hand photo, set well away from the others. The curl of smoke from the distant hut confirms the location of the chimney at its rear.

Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

A close-up of the Browns in front of the mustering hut. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

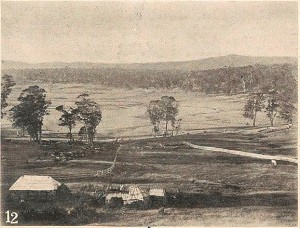

Perhaps the VDL Co did eventually submit to improvements. By 1905, when Jacky and Linda Brown were still in residence, there was a collection of buildings at Middlesex Station, including a ramshackle hut with a boarded-up window which was used by mustering stockmen and travellers. The main hut used by the Browns was set further east, away from these buildings, outside the House Paddock, which had now been fenced.

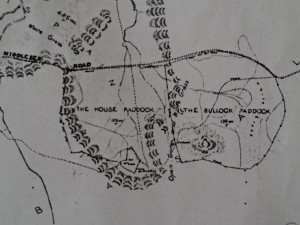

However, on the down side, the Fields were losing their unfettered reign over the highlands. A small land boom occurred in the upper Forth River country when a track was pushed through from the Moina region to Middlesex. The Davis brothers from Victoria tried to cultivate the Vale of Belvoir, and highland grazing runs were selected.[12] Frank and Louisa Brown were Fields’ Middlesex residents in November 1906 when Jack Geale, the new owner of the Weaning Paddock, asked new VDL Co agent AK McGaw to pay half the cost of fencing the eastern side of the Middlesex block, which would enable him to separate his herd from the Fields’.[13] McGaw sent surveyor GF Jakins with a team of men to Middlesex to re-mark the boundaries. The resulting survey shows the fenced paddock, the collection of buildings and the separate stockman’s hut.

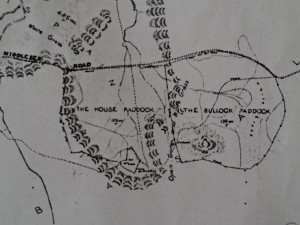

A crop from GF Jakins’ 1908 survey of the Middlesex Plains block, showing the House and Bullock Paddocks and the collection of buildings at the head of the House Paddock. From VDL343-1-359, TAHO, courtesy of the VDL Co.

Jakins also marked Olivia Falls (‘falls 300 ft’, ‘falls 60 ft’)—better known today as Quaile Falls—just outside the south-east corner of the Middlesex block. This casts doubt on the story of Quaile Falls being discovered by Roy Quaile while searching for stock.[14] The falls were probably known to the miners who worked the Sirdar silver mine nearby in the Dove River gorge from 1899—and were possibly given their present name in recognition of Wilmot farmer Bob Quaile’s visits there with tourists.[15] And what did the Aborigines call this ‘second Niagara’ long before that?

Perhaps it was knowledge of the ‘red’ pine growing on the south-western corner of the Middlesex Plains block that prompted Ron Smith of Forth to enquire about buying the block from the VDL Co.[16] That land owner would have enjoyed this attention. In 1908 Fields signed up for their second seven-year lease on Middlesex, at the increased rental of £150 per year. They had to agree to allow the VDL Co to sell any part of the Middlesex Plains block during that term excepting the 640 acres around the ‘homestead’.[17] As a regular visitor to Middlesex Station on his way to and from Cradle Mountain, Smith had no illusions about the standard of accommodation provided there. In January 1908 he and his party stayed in a new hut that had been built for the mustering stockmen. ‘We were very glad to do so’, Smith noted, ‘as the old hut was very much out of repair … ‘ It was a two-room hut with a moveable partition, so that it could be converted into one room as needed.[18]

A collection of Middlesex buildings in December 1909 or January 1910. These seem to be the same buildings visible in the 1905 photo. The main hut further east is not shown here. Ron Smith photo from the Weekly Courier, 22 September 1910, p.17.

Louisa Brown with a pet wallaby, January 1910. This appears to be the same main hut photographed by Montgomery in 1901. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

By December 1910 that hut was also in a state of disrepair. The Fields asked the VDL Co to renew or extend the two-roomed hut in time for the muster in the following month: ‘Up to now they have lived in the old house, but it is really unsafe. Mr Sanderson [VDL Co accountant] has seen the house that was built by us about four years ago, as he was there and stayed in it just after it was built. There is a man living there [Frank Brown] who would split the timber & do it’.[19]

Main hut at Middlesex Station, Christmas 1920. The figure second from right appears to be Dave Courtney, with moustaches but as yet no beard.

Ray McClinton photo, LPIC27-1-2 (TAHO)

Such is the incomplete photographic record of Middlesex Station at the time that it is unknown whether the mustering hut was replaced. However, we can say more about the main hut used by the stockman. The hut shown in the 1901 and 1910 photos appears to have remained the stockman’s hut in 1920 when Ray McClinton snapped it, this time with Dave Courtney the resident stockman. The chimney had been rebuilt with a vertical arrangement of palings, and a skillion had been added at the back. A prominent stump standing beside the hut in this photo must have been just out of picture in Montgomery’s 1901 shot.

After Fields had rented Middlesex from the VDL Co for 82 years, in 1922 JT Field, son of the late John Field of Calstock, bought the block, ending the uncertainty about its future. However, the lone figure of 49-year-old stockman Dave Courtney was emblematic of the Fields’ dwindling presence in the highlands, and his long, flowing beard of the 1920s and 1930s would not have allayed the impression of a once vigorous enterprise slowly grinding to a halt.

[1] Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.24–29.

[2] Edward Curr, Outward Despatch no.215, 18 November 1840, VDL1/1/5 (TAHO).

[3] Inward Despatch no.291, 16 November 1857, VDL 1/1/6 (TAHO).

[4] Minutes of VDL Co Court of Directors, 16 February 1888, VDL201/1/10 (TAHO).

[5] Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 16 April 1875, VDL22/1/5 (TAHO).

[6] John Field offered to settle the matter by selling the wild cattle to the VDL Co for £100. See Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 7 July 1871. See also Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 14 October 1871 and 3 September 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[7] Douglas & Collins to James Norton Smith, 16 February 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[8] Ritchie & Parker to James Norton Smith, 31 October 1871, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[9] Minutes of VDL Co Court of Directors 3 October 1900, VDL201/1/11 (TAHO).

[10] WL Field to James Norton Smith, 19 January 1901, VDL22/1/32 (TAHO).

[11] WL Field to James Norton Smith, 30 April 1901 and 15 June 1901, VDL22/1/32 (TAHO).

[12] See Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.18–23.

[13] JW Geale to EK McGaw, 26 November 1906, VDL22/1/38 (TAHO).

[14] Leonard C Fisher, Wilmot: those were the days, the author, Port Sorell, 1990, p.150.

[15] See, for example, ‘The Cradle Mountain’, Examiner, 5 January 1909, p.6.

[16] AK McGaw to Ron Smith, 23 January 1905, NS234/1/18 (TAHO). The term ‘red pine’ was often used indiscriminately to describe both the King Billy (Athrotaxis selaginoides) and pencil (Athrotaxis cupressoides) pine timber.

[17] WL Field to AK McGaw, 24 September 1908, VDL22/1/40 (TAHO).

[18] Ron Smith, ‘Trip to Cradle Mountain: RE Smith and the Adams Brothers, January 1908’, in Ron Smith, Cradle Mountain, with notes on wild life and climate by Gustav Weindorfer, the author, Launceston, 1937, pp.67–77.

[19] WT and JL Field, writing on behalf of WL Field, to AK McGaw, 7 December 1910, VDL22/1/42 (TAHO).