by Nic Haygarth | 29/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

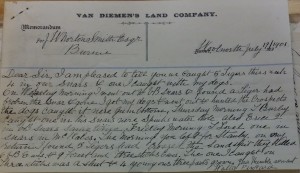

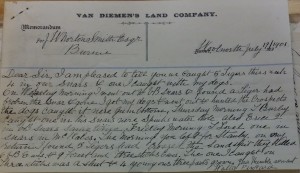

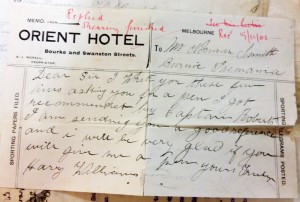

Tigers to the left, tigers to the right … VDL Co stockman Walter Pinkard reports from the thick of the Woolnorth tiger action 8 June 1901. From VDL22-1-32 (TAHO).

How do you stigmatise an animal? Try branding. The change from ‘hyena’ to ‘tiger’, as the common descriptor for the thylacine, was a major step in its reinvention as a sheep killer. Both ‘tiger’ and ‘hyena’ were used commonly to describe the thylacine during much of the nineteenth century, with ‘tiger’ only becoming the dominant term late in that century and into the twentieth century. For example, the records of the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) show that the company’s local officers used ‘hyena’ almost universally to describe the thylacine during the company’s first period of farming its Woolnorth property, in the years 1827–51—whereas later they went exclusively with ‘tiger’.

The stripes on the thylacine’s back presumably prompted the original attributions of the names ‘tiger’ and ‘hyena’, by Robert Knopwood and CH Jeffreys respectively.[1] The Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) and the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) were mentioned regularly in nineteenth-century newspaper items about life in the British Raj, which some foreign-born Tasmanians had also visited. Tigers, leopards, cheetahs, wolves and, less often, hyenas, preyed on stock and sometimes people in India. Government rewards were offered there for killing tigers. While the fearsome tiger was the favourite ‘sport’ of Indian big game hunters, the hyena, unlike its some-time Tasmanian namesake, was not the primary carnivore in the Bengali ecology. It was sometimes reported to be ‘cowardly’, ‘skulking’ and lacking in the fight desired by the game hunter.[2]

Likewise, the thylacine was also often described as ‘cowardly’ in its alleged sheep predations.[3] By the 1870s and 1880s, however, when the profitability of the wool industry was declining, those employed in the industry seem to have used the term ‘tiger’ almost universally to describe the thylacine. Perhaps shepherds preferred ‘tiger’ because it glamorised their profession, introducing an element of danger and likening them to the big game hunters of India. The way in which some thylacine killers made trophies of their kills and were photographed with these suggests identification with big game hunting.[4] By the same token, dubbing the thylacine a ‘tiger’ provided a potential scapegoat for sheep losses, enabling the shepherd to shift the blame for his own poor performance on to what may henceforth be perceived as a dangerous predator. Wool-growers wanting to eliminate the thylacine would also be keen to cast it as a dangerous predator. John Lyne, the east coast wool-grower who led the campaign for a government thylacine bounty, referred to the animal as a ‘tiger’ but also as a ‘dingo’, thereby equating the thylacine with the well-known mainland Australian sheep predator.[5] In 1887 ‘Tiger Lyne’s campaign was mocked to the effect that

‘the jungles of India do not furnish anything like the terrors that our own east coast does in the matter of wild beasts of the most ferocious kind. According to ‘Tiger Lyne’, these dreadful animals [thylacines] may be seen in their hundreds stealthily sneaking along, seeking whom they may devour …’[6]

The VDL Co correspondence records show that the company’s local agent James Norton Smith also originally described the thylacine as a ‘hyena’. He appears to have adopted ‘tiger’ as a descriptor in 1872 after his Woolnorth overseer, Cole, used the term in a letter to him. James Wilson, Woolnorth overseer 1874–98, also used the term ‘tiger’ exclusively, and after 1876 Norton Smith followed suit. The term ‘hyena’ was not used in any correspondence written or compiled by VDL Co staff, in Woolnorth farm journal records or Woolnorth accounting records in the years 1877–99. While Norton Smith occasionally used the term ‘hyena’ in the years following Wilson’s retirement from Woolnorth, ‘tiger’ remained his preferred term and this continued to be used exclusively at Woolnorth.

Theophilus Jones: thylacine prosecutor

As Robert Paddle and others have suggested, pastoralists generally blamed the thylacine as well as the rabbit for their declining political power and wealth.[7] One of the greatest prosecutors of the thylacine at this time was Theophilus Jones. In 1877–78 and 1883–85 two young British journalists toured Tasmania writing serialised newspaper accounts of its districts. Since both were newcomers, with limited knowledge of the colony, they could be expected to repeat unquestioningly much of what they were told. The first of these writers, E Richall Richardson, travelled all the populated regions of Tasmania except the far north-west and Woolnorth. On the east coast, Richardson interviewed woolgrowers, including John Lyne, the MHA for Glamorgan who a decade later would petition to establish the thylacine bounty. Richardson’s only comment upon the thylacine as a sheep killer or any kind of nuisance in his 92-part series was not on the east coast or in the Midlands, but in reference to the twice-yearly visits of graziers to their Central Plateau stock runs:

‘If when the master comes up, and there is a deficit in the flock, the rule is ‘blame the tiger’. The native tiger is a kind of scape-goat amongst shepherds in Tasmania, as the dingo is with shepherds in Queensland; or as ‘the cat’ is with housemaids and careless servants all over the world. ‘It was the cat, ma’am, as broke the sugar-basin’; and ‘It was the tigers, sir, who ate the sheep’.[8]

Theophilus Jones, in his 99-part series written in the years 1883–85, told a different tale. By this time, only half a decade since Richardson wrote, the wool industry had declined markedly. The first ‘stock protection’ association, that is, a locally subscribed thylacine bounty scheme, was formed at Buckland on the east coast in August 1884 while Jones was touring the area.[9]

Jones’ circumstances were different to the earlier writer’s. Although travelling in poverty, Richardson was a single man with no commitments. Jones, on the other hand, was trying desperately to support a wife and large family. While travelling Tasmania as a newspaper correspondent, he doubled as an Australian Mutual Provident (AMP) assurance salesman. Much more than Richardson, Jones concentrated on populated areas where he might sell assurance and find well-to-do patrons. He not only visited Woolnorth but practically every large grazier in the colony, and he flattered men who were in a position to financially benefit him. Whether currying favour or being merely ignorant of the truth, it is not then surprising to find Jones spouting woolgrowers’ vituperative against the thylacine. Henry, John and William Lyne appear to have fed Jones a litany of almost six decades of warfare with Aborigines and the wildlife, as if these were age-old predators: ‘Blacks and tigers made the life of a young shepherd one of continued mental strain’.[10] For Jones the tiger was generally the biggest killer of sheep, followed by the devil and the ‘eaglehawk’. The thylacine had ‘massive’ jaws, ‘serrated’ teeth and a powerful body like that of a kangaroo dog.[11] It was ‘a great coward’, savaging lambs but refusing battle with man or dog.[12] Jones applauded the stock protection association, hoping that it would reduce eagles and tigers ‘to the last specimen’.[13] That is, drive them to extinction.

Jones had already visited Woolnorth. He found that, like his predecessors, tigerman Charlie Williams kept ‘trophies’ at Mount Cameron, his prize being a thylacine skin 2.3 metres long.[14]

Like Williams, the government was actually more interested in possums. It had cited increased hunting, in response to high skin prices, as a reason to introduce the Game Protection Amendment Act (1884), which protected all kinds of possum during the summer, allowing open season from April to July inclusive. During debate about the bill in the House of Assembly, James Dooley ‘likened the sympathy for the native animals to that which was excited in favour of the native race’, to which MHA for Sorell, James Gray, responded that ‘the only resemblance between the natives and the opossums were that they were both black. (Laughter.)’[15]

It was also Gray who in 1885 asserted the ‘necessity of something being done to stop the ravages of the native tiger in the pastoral districts of the colony …’.[16] John Lyne took up this stock protection measure: a £1 per head thylacine bounty operated from 1888 to 1909. About 2200 bounties were paid across Tasmania, helping to drive the animal towards extinction. Bounties were paid by the Colonial Treasurer upon thylacine carcasses being presented to local police magistrates or wardens.

Woolnorth was a remote settlement with challenges faced by few wool-growing properties. Distance from towns, doctors and schools was probably one reason that it was so difficult to find and keep a reliable man to work at Mount Cameron West in particular. Time and time again James Wilson’s farm journals record the Mount Cameron West shepherd’s monthly visits to the main farm at Woolnorth to get supplies and return with them to his own hut: ‘Tigerman came down’ and ‘Tiger went home’. ‘Tigerman’, which carries the implication of being a dedicated thylacine killer, may have been coined to glamorise the position in order to attract staff. It and the general use of the term ‘tiger’ at Woolnorth may also indicate that the overseer, his stockman and farm hands wanted to shift the blame for sheep losses on the property.

Table 3: Occurrences of various names for the thylacine in Tasmanian newspapers for the years 1816–1954 (in both text and advertising), taken from the Trove digital newspaper database 22 December 2016

| NAME |

1816–87 |

1888–1909 |

1910–54 |

TOTAL |

| Tasmanian tiger |

141 (84–57) |

96 (64–32) |

434 (420–14) |

671 (568–103) |

| Native tiger |

326 (199–127) |

197 (186–11) |

88 (88–0) |

611 (473–138) |

| Tasmanian native tiger |

5 (5–0) |

0 (0–0) |

7 (7–0) |

12 (12–0) |

| Thylacine/thylacinus |

43 (43–0) |

20 (20–0) |

93 (91–2) |

156 (154–2) |

| Hyena/native hyena/opossum hyena |

165 (107–58) |

46 (39–7) |

84 (77–7) |

295 (223–72) |

| Dog-faced opossum |

1 (1–0) |

0 (0–0) |

0 (0–0) |

1 (1–0) |

| Tasmanian wolf |

9 (3–6) |

11 (11–0) |

97 (97–0) |

117 (111–6) |

| Marsupial wolf |

4 (4–0) |

6 (6–0) |

74 (74–0) |

84 (84–0) |

| Tiger wolf |

7 (7–0) |

3 (3–0) |

3 (3–0) |

13 (13–0) |

| Native wolf/native wolf-dog |

5 (5–0) |

0 (0–0) |

5 (5–0) |

10 (10–0) |

| Zebra wolf |

5 (5–0) |

6 (6–0) |

2 (2–0) |

13 (13–0) |

| Tasmanian tiger wolf |

1 (1–0) |

0 (0–0) |

0 (0–0) |

1 (1–0)[17] |

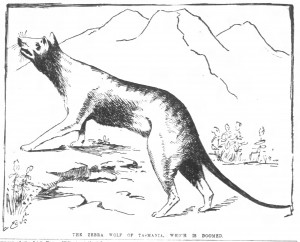

In her book Paper tiger: how pictures shaped the thylacine, Carol Freeman stated that ‘Tasmanian wolf’ and ‘marsupial wolf’ were the principal names given to the thylacine in the zoological world until well into the twentieth century, described how in the period from the 1870s to the 1890s ‘wolf-like’ visual images of the species predominated in natural history literature, and speculated that illustrations of this kind, repeated in mass-produced Australian newspapers in 1884, 1885 and 1899, ‘influenced perceptions close to the habitat of the thylacine and encouraged government extermination policies’.[18]

The National Library of Australia’s Trove digital newspaper database allows us to test the idea that the depiction of the thylacine as a ‘wolf’ or as ‘wolf-like’ had any traction in Tasmania. Unlike the inter-colonial illustrated newspapers to which Freeman referred—Australian Graphic (1884), Illustrated Australian News (1885) and Town and Country Journal (1899)—the Trove search represented by Table 3 is restricted to 88 Tasmanian newspaper titles, 23 of which published during at least part of the period of the Tasmanian government thylacine bounty 1888–1909. More than any other type of publication, the Tasmanian newspapers are likely to contain the language of ordinary Tasmanians, expressed either by journalists, newspaper correspondents or by themselves in letters to the editor—and they were more likely than any other form of publication to be read by and contributed to by graziers, legislators and hunter-stockmen involved in killing thylacines. Some of these newspapers carried occasional lithographed or engraved images, but the search does not include the two best-known Tasmanian illustrated newspapers, the Weekly Courier (1901–35) and the Tasmanian Mail/Illustrated Tasmanian Mail (1877–1935), which (in December 2016) were yet to be digitised for the Trove database. Trove coverage of Tasmanian newspapers begins with the Hobart Town Gazette and Southern Reporter in 1816 and goes no later than 1954 except in a few cases.

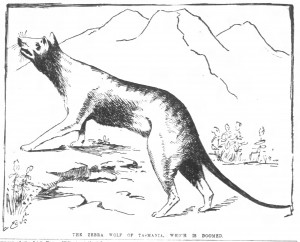

The Tasmanian ‘zebra wolf’, from the San Francisco Chronicle, 18 February 1896, p.6.

The Trove search suggests that in the period 1888–1909 the terms ‘native tiger’ (197 hits) and ‘Tasmanian tiger’ (96 hits) were much more widely used by the general public in Tasmania that any permutation of ‘wolf’ (26 hits altogether), and that ‘hyena’ (46 hits) was also more popular than ‘wolf’. While the 1884 issue of Australian Graphic which contained the illustration of the ‘Tasmanian zebra wolf’ is not included in the Trove search, it did pick up a description of that issue of the newspaper by the editor of the Mercury. Clearly he was not profoundly influenced by the engraving of the thylacine:

‘The illustrations are fairly good, excepting those which are apparently intended to be amusing; these amuse only by their extreme absurdity. There is a cut representing, what is termed, a Tasmanian zebra wolf. It is about as true to nature as the pictures exhibited outside a travelling menagerie’.[19]

The ‘Tasmanian wolf’ as a sheep devourer in 1947, when the term ‘wolf’ had gained some popular usage: from Hotch Potch (the magazine of the Electrolytic Zinc Company of Australasia), October 1947, vol.4, p.2 (TAHO).

The names ‘Tasmanian wolf’ (97 hits) and ‘marsupial wolf’ (74 hits) only gained traction in Tasmanian newspapers in the period (1910–54) when the thylacine was clearly disappearing or virtually extinct, that is, when the scientific and zoological community entered the popular press in its desperate search for a remnant thylacine population. This is also the period in which the Latin scientific name for the animal, thylacine, thylacinus (93 hits) occurred much more frequently in the Tasmanian press. However, even in this period, ‘tiger’ (529 hits) remained easily the predominant descriptor for the thylacine. The fact that the thylacine received more attention in the press during the years when it could not be found than when it could speaks for itself, although of course many more newspapers were published in the first half of the twentieth century than in the nineteenth.

[1] Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian tiger: a lesson to be learnt, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, 1998, p.15.

[2] ‘Pigsticking in India’, Launceston Examiner, 29 March 1897, p.3; ‘Shikalee’, ‘Wild sport in India’, Launceston Examiner, 24 July 1897, p.2.

[3] See, for example’, ‘Royal Society of Tasmania’, Courier, 16 June 1858, p.2; or ‘Town talk and table chat’, Cornwall Chronicle, 27 March 1867, p.4.

[4] See, for example, [Theophilus Jones], ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[5] See, for example, ‘Parliament’, Launceston Examiner, 1 October 1886, p.3.

[6] Tasmanian Mail, 3 September 1887; cited by Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000, p.161.

[7] See Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger.

[8] E Richall Richardson, ‘Tour through Tasmania: no.89: cattle branding’, Tasmanian Tribune, 14 March 1878, p.3.

[9] ‘Buckland’, Mercury, 15 August 1884, p.3.

[10] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.61’, Mercury, 8 November 1884, supplement, p.1.

[11] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.49’, Mercury, 26 July 1884, p.2.

[12] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[13] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.56’, Mercury, 20 September 1884, p.2.

[14] Theophilus Jones, ‘Through Tasmania: no.35’, Mercury, 26 April 1884, supplement, p.1.

[15] ‘House of Assembly’, Mercury, 24 October 1884, p.3.

[16] ‘Meeting at Buckland’, Mercury, 14 August 1884, p.2; ‘The native tiger’, Mercury, 25 September 1885, p.2.

[17] This list was compiled on 22 December 2016. The numbers in brackets indicate how many of the hits occurred in text and how many in advertising. While occurrences of a name in advertising are a relevant gauge of its public usage, it is recognised that numbers of hits are exaggerated by repeated publication of the same advertisement. Another issue noted in this search of Trove was the need to weed out references to ‘native and tiger cats’, which refer to the two species of quoll rather than to the thylacine. There are also cases of repetition in the sense that some textual references involve two or more names for the thylacine, such as ‘the Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf’. In such cases both names have been included in the table.

[18] Carol Freeman, Paper tiger: how pictures shaped the thylacine, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.117and 140.

[19] Editorial, Mercury, 28 March 1884, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 28/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

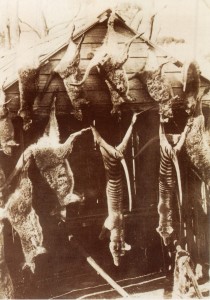

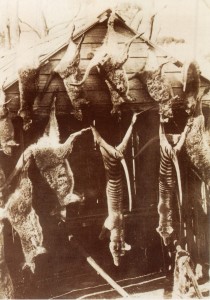

A photo of two thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) carcasses suspended from a hut in Waratah, Tasmania, has intrigued students of the animal’s demise. Who killed these tigers? Eric Guiler speculated that they might have been taken by a Waratah hunter John Cooney who collected two government thylacine bounties in 1901.[1]

In fact the photographer, Arthur Ernest Warde, was himself a hunter and future Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, and the photo probably depicts his own kills. The man in question was a wheeler and dealer who spent three decades in Tasmania, turning his hand to any useful practical skill—including photography and exploiting the fur trade. The terms of Warde’s stint at the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s (VDL Co’s) Woolnorth property in the years 1903–05 confirm that, far from being specialist thylacine killers, the so-called Woolnorth tigermen were simply regular hunter-stockmen who also took responsibility for managing snares set for thylacines at Green Point near latter-day Marrawah. Given this collision of photographer and tiger snarer, it is tantalising to wonder what tiger-related photos Warde took while working at Woolnorth that may still remain undiscovered in a family scrapbook, or which may have long since mouldered away in someone’s back shed, lost for all time.

Ernest Warde photo of Maori chiefs, 1998:P:0383, QVMAG

Warde’s early life remains as mysterious as his tiger photo. In Wellington, New Zealand in 1890 he married renowned whistler and music teacher Catherine Elizabeth Walker, née Dooley, the daughter of Zeehan shopkeeper Joseph Benjamin Dooley and his wife Annie Dooley.[2] The Wardes, both of whom were known by their middle name, appear to have been in Bendigo in 1891 and by 1893 had relocated to Inveresk, Launceston, where the photographer, ‘late of New Zealand’, presented images of Maori chiefs to the Queen Victoria Museum.[3] The couple’s first child, Winifred Warde, was born at Launceston in 1893.[4]

The Warde photo of the two thylacine carcasses, from Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian tiger: a lesson to be learnt, p.129.

In 1896 the Wardes were in Devonport, in 1897 in Waratah, where second daughter Mabel was born.[5] Elizabeth taught music in both towns.[6] It was supposedly at Waratah that Warde took the intriguing photo, which shows two thylacine and eight wallaby carcasses hanging from the front of a building more closely resembling a woodshed than a hunting hut. The photo slightly pre-dates the era of the skinshed, the unique Tasmanian invention which revolutionised high country hunting by enabling hunters to dry large numbers of skins without leaving the high country. In fact, the photo does not show drying skins, but carcasses which are yet to be skinned. What is the purpose of the image? It is not the conventional trophy photo, which would pose the hunter with his trophy kill. Warde himself collected two thylacine bounties, ten months apart, in September 1900 and July 1901, while living at Waratah, where he probably learned to hunt.[7] Just as the bushman Thomas Bather Moore celebrated in verse the incident in which one of his dogs killed a ‘striped gentleman’, perhaps for Ernest Warde the novelty of killing a thylacine or two justified commemoration or memorialisation of the event with a photo. It is likely that he killed at least one of the thylacines in the photo, and afterwards submitted it for the government bounty.

Warde’s Osborne Studio photo of the fire at ER Evans boot shop and house, Burnie.

From the Weekly Courier, 1 March 1902, p.17.

Warde’s Osborne Studio photo of EJ Wilson’s children, 1986:P:0045, QVMAG.

Warde was one of many to have practised photography in Waratah, and with the town’s population still growing, he would not be the last. However, in December 1901 a better photographic opportunity arose in a coastal centre, Burnie, when John Bishop Osborne decided to move on. Warde took over Osborne’s Burnie studio, while also operating a farm at Boat Harbour and advertising his and Elizabeth’s services as musicians.[8] In 1902, while Elizabeth was busy producing the couple’s third child, Francis Harold Warde, photos credited to Warde and to Warde’s Osborne Studio photos appeared in the Weekly Courier and Tasmanian Mail newspapers.[9]

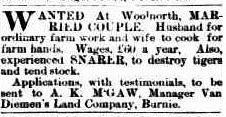

The tigerman job advertised, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 22 May 1903, p.3.

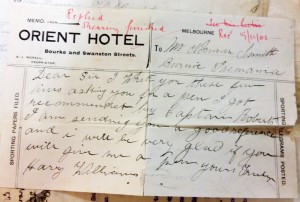

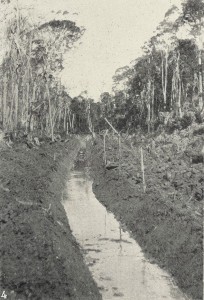

Warde appears to have made the acquaintance of VDL Co agent AK McGaw while supplying photos to the company. The photography business must not have been lucrative, as in May 1903 he agreed to replace the gaoled George Wainwright as the Mount Cameron West tigerman.[10] Warde’s contract as ‘Snarer’ shows him to be a general stockman and farm hand engaged for the Mount Cameron West run, with the killing of ‘vermin’ (that is, all marsupials) his primary duty:

‘It is hereby agreed that the Snarer shall proceed to Mount Cameron Woolnorth … and shall devote his time to the destruction of Tasmanian Tigers, Devils and other vermin and in addition thereto shall tend stock depasturing on the Mount Cameron Studland Bay, and Swan Bay runs, also effect any necessary repairs to fences and shall immediately report any serious damage to fences or any mixing of stock to the Overseer & shall assist to muster stock on any of the above runs whenever required to do so & generally to protect the Company’s interests shall also prepare meals for stockmen when engaged on the Mount Cameron Run’.

The pay was £20 plus rations (meat, flour, potatoes, sugar, tea, salt, with a cow given him for milk) with the snarer providing his own horse.[11] A butter churn was later provided, and farm manager James Norton Smith added that ‘when he wants a change he can catch plenty of crayfish’.[12] No rent was paid for the Mount Cameron West Hut, and the former company reward of £1 per thylacine still applied. In addition, the VDL Co agreed to supply the snarer ‘with hemp and copper wire for the manufacture of tiger snares only (the Snarer supplying such materials as he may require for Kangaroo or Wallaby snares)’.[13] That is, the necker snares used to catch thylacines were stronger than those used to catch wallabies and pademelons. It was the same deal as for his predecessors: the company supplied a small wage and rations, encouraging the stockman-hunter to protect his flock by killing thylacines and keep the grass down by killing other marsupials. In July 1904 Warde advertised in the newspaper for an ‘opossum dog’, which he was willing to exchange for a ‘splendid kangaroo dog’. He knew that the best money was in brush possum furs.[14]

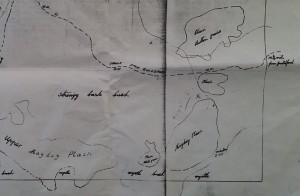

Warde was the last stockman-hunter based at Mount Cameron West. Nearing the close of 1904 he was also trying to ‘get a good line of snares down from the Welcome [?] forest into the back of the Studland bay knolls’, which would give him ‘a splendid tiger break …’[15] However, he had probably already landed the last of his twelve thylacines for the company. In February 1905 the Mount Cameron West Hut was burnt down, Warde’s family escaping the flames late at night in the breadwinner’s absence.[16] That the hut was not replaced for years confirms that the thylacine problem, real or perceived, had abated.[17]

After leaving Mount Cameron West, Ward ditched the ‘e’ from the end of his surname and complemented the Boat Harbour farm with a general store. The Wardes remained there until in 1923 they sold up their store to Hamilton Brothers of Myalla and relocated to New Zealand, where A Ernest Warde reattached his ‘e’ and reinvented himself firstly as an Otago real estate agent, working for his father-in-law, then as an Auckland used car salesman.[18] Elizabeth Warde disappeared from the picture and, appropriately, Ernest wound back his personal odometer to 49 years when in 1932 he took his new 33-year-old bride Mary Winifred Tremewan to see England and America.[19] The new marriage ended when the couple was living in Sydney in the mid-1940s.[20] Warde’s death certificate, in July 1954, described him as an ‘investor’. In truth, he was a trans-Tasman jack-of-all-trades who happened to be the last of the Woolnorth tigermen.[21]

[1] Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard, Tasmanian Tiger: a lesson to be learnt, Abrolhos Publishing, Perth, 1998, p.129. Cooney’s bounty payment was no.249, 19 June 1901 (2 adults, ’11 June’), LSD247/1/ 2 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [hereafter TAHO]).

[2] For her prowess as a whistler, see ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 15 January 1894, p.5; ‘Burston Relief Concert’, Daily Telegraph, 16 January 1894, p.3 and ‘Entertainment at the Don’, North West Post, 21 April 1894, p.4. Elizabeth Walker is the mother’s name given on the couple’s three children’s birth certificates. On the 1903 Electoral Roll her name is given as Catherine Elizabeth Warde.

[3] ‘Australian Juvenile Industrial Exhibition’, Ballarat Star, 26 May 1891, p.4; ‘The Museum’, Launceston Examiner, 23 December 1893, p.3.

[4] She was born 31 August 1893, birth registration no.606/1893, Launceston.

[5] In 1896 E Warde of West Devonport advertised to sell a camera, lens and portrait stand (advert, Mercury, 23 May 1896, p.4). In 1897 the Wardes featured in a Waratah dance (‘Plain and Fancy Dress Dance’, Launceston Examiner, 9 October 1897, p.9). Mabel Warde’s birth was registered as no. 2760/1898, Waratah.

[6] Advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 January 1902, p.3.

[7]; Bounties no.293, 18 September 1900 (’11 September’); and no.305, 12 July 1901, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[8] See advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 December 1901, p.4; ‘Table Cape’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 19 November 1901, p.2. John Bishop Osborne, the former Hobart photographer, had been on the move every few years since setting up at Zeehan in 1890. Osborne moved to Penguin, and he would end his days in Longford, where he lived 1921–34. Ernest and Elizabeth Warde advertised that they were available to supply music to parties and balls, while Elizabeth also sought piano, organ and dance students (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 January 1902, p.3).

[9] Francis Harold Warde was born at Alexander Street, Burnie, on 17 December 1902 (registration no. 2061/1903). Catherine Elizabeth Warde and Ernest Warde were listed at Burnie on the 1903 Electoral Roll.

[10] The new operator of the Osborne Studio was Mr Touzeau of Melba Studio, Melbourne (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 27 June 1903, p.1). Warde held a furniture sale at his Alexander Street, Burnie, residence in June 1903 (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 13 June 1903, p.3) and advertised for a ‘strong quiet buggy Horse and good double-seated Buggy (tray-seated preferred …’ (advert, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 8 June 1903, p.3).

[11] For Warde’s proposed rations, see James Norton Smith to AK McGaw, 4 June 1903, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[12] James Norton Smith to AK McGaw, 4 June 1903; Ernest Warde to AK McGaw, 7 October 1903, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[13] Agreement between the VDL Co and Ernest Warde, 29 May 1903, VDL20/1/1 (TAHO).

[14] Advert, North West Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 26 July 1904, p.3.

[15] E Warde to AK McGaw, 22 December 1904, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Marrawah’, North West Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 February 1905, p.2.

[17] Woolnorth farm journal, 3 February 1905, VDL277/1/32 (TAHO).

[18] ‘Boat Harbor’, Advocate, 31 January 1923, p.4; ‘Bankruptcy’, Auckland Star, 27 September 1929, p.9.

[19] Did Elizabeth Warde die or did the couple divorce? No record of her was found. According to their marriage certificate (registration no.8401/1929), Mary Winifred Tremewan was born in New Zealand in October 1898. For their ten-month English and American holiday, see ‘The social round’, Auckland Star, 6 January 1933, p.9 and UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960. They sailed from Sydney to London on the Ormonde.

[20] Record no.1208/1944, Western Sydney Records Centre, Kingswood, NSW.

[21] Warde was not the last man to kill thylacines at Woolnorth, but the last in a long line of hunter-stockmen appointed specifically to Mount Cameron West to look after stock and manage the thylacine snares at Green Point.

by Nic Haygarth | 20/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

Ever felt the need to turn the orthodox version of history on its head, and look at it upside down? Sometimes I want to write history from the ground up, from the perspective of people at the bottom of the food chain. With that in mind, I once set out to try to prove that the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) was primarily a fur farmer during its first century, that is, that more money was generated by the culling of marsupials on its land than by grazing and agriculture. Unfortunately, there are few surviving records of the skins sales of disparate hunter-stockmen employed by the company, making the task very difficult.

That the VDL Co learned to exploit the fur trade emphasises that the company’s survival for nearly 200 years has pivoted on its flexibility. When wool-growing failed, it withdrew, leased its lands and waited for the right time to return as a wool, dairy, beef, timber and brick producer. When it could find no minerals on its lands, it built a port and established a railway so that it could exploit other people’s mineral exports. It sold its land and its timber. When the fur trade peaked in the 1920s it exploited that. Now it is referred to as Australia’s biggest dairy farmer. Is high-end heritage tourism or Chinese niche tourism the next chapter in the story of Woolnorth, the VDL Co’s remaining property?

Just to rewind a little, the hunter-stockmen who worked the VDL Co’s land had always exploited the fur trade. It was part of their employment obligations: we pay you a small wage, thus giving you the incentive to increase your income by killing all the grass-eating marsupials and all potential predators (tigers, wild dogs and eagles) of sheep, and thereby conferring a mutual benefit. You sell the marsupial skins, and we will even throw in a bounty for every predator you kill.

The killing of predators represented a bonus for hunter-stockmen whose main game was killing wallabies, pademelons and possums. By 1830 thylacines were being blamed for killing the company’s sheep, although it is clear that poor pasture selection and wild dogs were bigger problems. After the catastrophic loss of 3674 sheep at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills in the years 1831–33 to severe weather conditions and the attacks of wild animals, it was decided to temporarily cease grazing sheep there, transferring that stock to Circular Head and Woolnorth.[1] In 1830 a £1 bounty was offered for the killing of a particular thylacine at Woolnorth.[2] From 1831 the VDL Co paid a regular reward for killing thylacines on its properties, initially 8 shillings, later 10.[3] The Court of Directors in London seemed to panic about the company’s prospects, stating that ‘We fear the hyenas and wild dogs, more than climate’.[4] The dilemma of the dog problem is clear. Requests for a thylacine-killing dog for Woolnorth were matched by reports of sheep depredations of dogs belonging to Woolnorth servants.[5] In 1835–37 the VDL Co employed a dedicated ‘pest controller’, James Lucas, to kill wild dogs and thylacines at first at the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, then at Woolnorth.[6] Lucas, a ticket-of-leave convict, could be said to have been the first Woolnorth ‘tigerman’, although he was never referred to by that name and was employed there only briefly.[7] He operated on the same thylacine bounty of half a guinea. Whether due to Lucas’ performance or other influences, stock losses at Woolnorth dropped dramatically during his time there and the panic over thylacines and wild dogs subsided. However, bounty payments for the killing of predators had been resumed by 1850, as the following table illustrates:

Rewards paid by the VDL Co for the killing of predators at Woolnorth 1850–51

| Name |

Time |

Program |

Kill |

Payment |

| Edward Marsh |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena |

5 shillings |

| A Walker |

Aug 1850 |

Merino sheep |

Two hyenas |

10 shillings |

| Richard Molds |

Aug 1850 |

Cross bred Leicester sheep |

Three dogs |

15 shillings[8] |

| A Walker |

Nov 1850 |

Improved sheep |

Hyena |

£1-2-11[9] |

| Richard Molds |

Feb 1851 |

Leicester sheep |

Dog |

5 shillings[10] |

| A Walker |

Sep 1851 |

Merino sheep |

Hyena & Two Eagle Hawks |

4 shillings 6d[11] |

| W Procter |

Dec 1851 |

Woolnorth |

Hyenas |

10 shillings[12] |

VDL Co withdrawal and the Field brothers on the Surrey Hills

In 1852 the VDL Co withdrew from Van Diemen’s Land, becoming an absentee landlord and, by 1858, its Hampshire and Surrey Hills and Middlesex Plains blocks were all leased to the Field family graziers. Tasmanian furs were already renowned, even before a market was found for them in London. Tasmanian bushmen and excursionists favoured possum-skin rugs as bedding. The best brush possum rugs to be had in Melbourne were reputedly those made by Tasmanian shepherds from snared skins, where the animals grew larger and more handsome than their Victorian counterparts.[13]

Fields’ outposted hunter-stockmen invariably hunted for meat, skins and clothing, burning off the surrounding scrub and grasslands to attract game. When an 1871 party visited the Hampshire Hills station, the peg-legged Jemmy, who was the designated cook, whipped up wallaby steaks. At the Surrey Hills, Charlie Drury, a delusional ex-convict hunter-stockman whom Fields inherited from the VDL Co, fed them cold beef, and the visitors got to try those famous possum-skin rugs, which, as was customary, were alive with fleas. While his guests battled these, Drury went ‘badger’ (wombat) hunting by the light of the moon with about a dozen kangaroo-dogs, bringing home three skins and one entire animal—presumably for breakfast. As he explained at the dining table, ‘the morning after I have been out badger-hunting at night I always eat two pounds of meat for breakfast, to make up for the waste created by want of sleep’. Travelling further, the party found that Jack Francis, stockman at Middlesex Plains, made his family’s boots and shoes from tanned hides. He also tanned brush possum skins for rugs, which again formed the bedding—flealessly this time.[14]

Records of hunter-stockman sales of skins from this period are scant. A rare example is an account in the VDL Co papers of its Mount Cameron West ‘tigerman’ William Forward sending 180 wallaby and 84 pademelon skins to market in April 1879.[15] In 1879 the open season for ‘kangaroo’ (wallaby) was from 31 January to 31 July, suggesting that Forward’s haul represented at most two months’ worth out of a six-month season.[16] By market prices of the time these skins would have been worth at least £8–4–0 and at most £14–14–0. If we assume that his haul for the six-month season was three times as much, we can imagine him earning at least as much as his annual wage of £20–£30. And that is without bonuses for thylacine killings.

Luke Etchell, career bushman

While Charlie Drury was drinking himself to death at his hunting hut on Knole Plain, and the VDL Co plotting the removal of Fields and all their wild cattle from the Hampshire and Surrey Hills, Luke Etchell was a child growing up fast. He was the son of John Etchell or Etchels, a transported ex-convict harking from rural Lancashire. How many of the sins of the father were visited on the son? By the time of his transportation at the age of fifteen, John Etchell had already racked up convictions for housebreaking, theft, assault and, perhaps most telling of all, vagrancy. He was illiterate.[17] While still a convict in Van Diemen’s Land, he twice saved someone from drowning. [18] However, the negative side of the ledger kept him in the convict system. Christopher Matthew Mark Luke Etchell—a child with most of the Gospels and more—was born to John and Mary Ann Etchell, née Galvin, at Stanley, on 17 December 1868, as perhaps their fourth child.[19] (The origins of Mary Ann Galvin or Galvan have so far proven elusive.[20]) His family lived in a hut at Brickmakers Bay which was destroyed by fire in 1874, then appears to have moved to Black River, at a time when payable tin had been found at Mount Bischoff and specks of gold in west- and north-flowing rivers.[21] John Etchell worked as a labourer, a paling splitter and a prospector who claimed to have found gold eighteen km south-east of Circular Head in 1878.[22]

Life was not harmonious or easy, however, as suggested by Mary Ann Etchell’s successful application for a protection order against her husband in August 1880. In the court proceedings she alleged that about a year earlier he had threatened to sell everything in order to raise money to get him to Melbourne, where she supposed he was now. For the last five months all he had contributed for the upkeep of his family was 228 lb (103 kg) of flour and one bag of potatoes. [23] It seems that the family never saw John Etchell again and, given the request for a protection order, they were probably glad about it.

Certainly Luke Etchell became self-reliant very quickly. He claimed that at the age of nine, that is, in 1877, he was already working in a tin mine on Mount Bischoff and at one of the stamper batteries at the Waratah Falls, and it is true that, almost in the Cornish tradition, young boys found mining work of this kind.[24] (One of his contemporaries as a bushman, William Aylett, born in 1863, claimed to have been learning how to dress tin at Bischoff at the age of thirteen in 1876.[25]) His English-born relative John Wesley Etchell was certainly established in Waratah by December 1878, operating a shop owned by the ubiquitous west coaster JJ Gaffney, and the family made the move there, presumably with John Wesley Etchell as the major breadwinner. [26] Luke, like some of his brothers and sisters, had at least one brush with the law in his youth.[27]

Even ‘Black’ Harry Williams the tiger killer needed to go shearing for additional income. Here he asks the VLD Co for a shearing pen in 1901. From VDL22-1-31 (TAHO).

Etchell was probably with his family at Waratah until at least 1886, when he was eighteen. Over the next two decades he became an expert bushman, apparently commanding familiarity with all the country between the lower Pieman River and Cradle Mountain.[28] His base was at Guildford Junction, the village centred on the junction of the VDL Co’s lines to Waratah and Zeehan, on the hunting territory of the Surrey Hills. He also became handy with his fists, featuring in a public boxing match in 1902.[29] Other hunters, successors to Drury, were working the Surrey and Hampshire Hills. By 1900 ‘Black’ Harry Williams, for example, the ‘colored [sic] king of the forest’, was building a reputation as a tiger tamer on the Hampshire Hills, even showing a live one in Burnie which he intended to sell to Wirth’s Circus.[30] Williams probably collected four government thylacine bounties, whereas Etchell collected only one, in 1903, most of his incidental tiger kills coming after the bounty was abolished.[31]

In 1910 ‘Tasmanian Chinchilla (clear blue Australian possum)’ took its place in the American fur catalogue alongside Hudson seal, skunk, beaver, wolf and chamois. Advert from the Chicago Daily Tribune, 17 December 1910, p.26

By 1905 Etchell was sufficiently well known as a bushman of the high country to be recommended as the man to lead a search for Bert Hanson, the seventeen-year-old lost in a blizzard on the eastern side of Dove Lake.[32] Making a living as a bushman meant grasping every opportunity that came along, be it splitting palings, cutting railway sleepers, taking a contract to build or repair a road or working an osmiridium claim. In 1910, for example, Etchell’s £30 tender for work on the road at Bunkers Hill was accepted by the Waratah Council.[33] In 1912 he obtained a tanner’s licence, suggesting that he intended to deal in skins.[34]

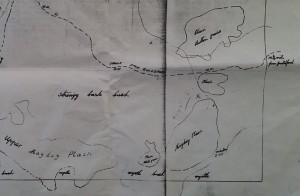

‘X’ marks the spot. The Etchell Mayday (First of May) Plain hut raided by police in 1937 in the south-western corner of the Surrey Hills block. Note also the prospectors’ camp marked nearby. From AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

However, it was as a snarer that Etchell made his reputation. He would have learned how to hunt as a boy from his father or brothers. Like the Ayletts, the Etchell family dealt extensively in the fur trade. Luke’s brother William snared and bought skins.[35] His cousin Harold Reuben Etchell had run-ins with the law over skin dealings, being the subject of a police stake-out and raid on a hut on the Mayday Plain (now First of May Plain).[36] Ernest James Etchell was another hunter who tested or blurred the hunting regulations.[37] However, Luke struck up a partnership with his brother Thomas, who also dabbled in prospecting.[38]

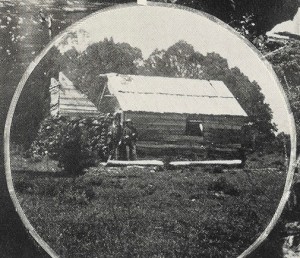

Atkinson’s hut and skin shed at Thompsons Park, on the Surrey Hills block. Thompsons Park was the site of a Field brothers’ stock hut. Later it also served seasonal hunters.

The pile of rubble or huge chimney butt beside Atkinson’s hut from a previous building on the Thompsons Park site.

As outlined previously, having hunters remove the plentiful game from its remaining land benefited the VDL Co stock—and the company gained doubly by charging these men for the privilege. The VDL Co engaged Surrey Hills hunters on a royalty system of one-sixth of their skins taken. In February 1912, for example, its Guildford man Edward Brown told its Tasmanian agent AK McGaw that Thomas Etchell had requested a run near the Fossey River, whereas R Brown wanted the 31 Mile or the West Down Plain (which turned out to be outside the Surrey Hills boundary). ‘I have told them that they must report to me before sending any of their skins away’, he wrote, ‘so I can count them and retain two out of every dozen for the company …’ [39] The disadvantage of this system for the VDL Co was that hunters could cheat, and later that season Brown claimed that DC Atkinson and Luke Etchell were not submitting all their skins to him from a lease Atkinson had taken on ‘the Park’. Brown found particular fault with their second load of skins:

‘The next lot was over 1½ cwt and Etchell gave me 11 which weighed 8 lbs and said “that was his share” but Atkinson would not give any as he caught them on his own ground. I know for sure he as [sic] snares set other than on his own ground. I think he was given the right on the conditions he gave 2 in the dozen regardless of where they were caught. Anyhow Atkinson should have given 11 and that would leave about ½ cwt to come off his own ground …’[40]

Ironically, the Animals and Birds Protection Act (1919) ushered in perhaps the greatest marsupial slaughter in Tasmanian history. In the open season winters from 1923 to 1928 about 4.5 million ringtail possum, brush possum wallaby and pademelon skins were registered.[41] It is easy to imagine why at some stage the VDL Co increased its royalty on the Surrey Hills from one-sixth of all skins taken to one-third. It sent men with pack-horses around the leased runs every fortnight to collect skins. Harry Reginald Paine described a raid by police and VDL Co officers on a Waratah house owned by Joe Fagan which the company believed contained skins obtained without royalty payment from the Surrey Hills block.[42] However, the late 1920s and early 1930s were dark days economically, with only the 1931 gold price spike and government incentives like the Aid to Mining Act (1927) giving hope to rural workers. Many prospectors went looking for gold in the Great Depression years, and some got into trouble. In 1932 Luke Etchell and Cummings of Guildford sought and found the Waratah prospector WA Betts, after he was lost in the snow for two weeks. After giving him a good feed, they returned him to Guildford on horseback.[43] Again, Etchell was the man to whom people looked when someone went missing in the high country.

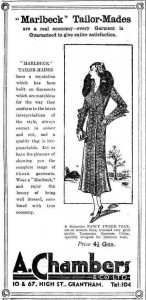

The fashionable British bride would not think of departing on her honeymoon without her Tasmanian brush possum collar coat in 1932. Advert from the Grantham Journal, 29 October 1932, p.4.

The open season of 1934, in which nearly a million-and-a-half ringtails were taken in Tasmania, was a godsend to the VDL Co which, during an unprofitable year for farming, made £500 out of hunting.[44] Thomas Etchell may not have been too wide of the mark when it predicted that an open season would benefit the community to the extent of £300,000–£400,000.[45] Did it benefit the possum population? The downside of that record-breaking season for hunters was that it was followed by two closed seasons while ringtail numbers recovered.

By the mid-1930s Luke Etchell was stockman for the shorthorn herds of RC Field’s Western Highlands Pty Ltd, which existed at least 1932‒38, and a regular correspondent with the police on hunting matters.[46] Ahead of the open season in 1937, for example, he advised Waratah’s Constable MY Donovan that ‘the Kangaroo and Wallaby were that numerous that they were eating the grass off and leaving the sheep and cattle on the runs short’.[47] Later that year, with the thylacine finally part protected and the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board keen to find living ones, Etchell was the ‘go to man’ for the Surrey Hills, Middlesex Plains, Vale of Belvoir and the upper Pieman. He suggested the hut in the Vale of Belvoir as a good base for the search.[48] He told Summers that ‘some years ago he has caught six or seven Native Tigers during a hunting season but for many years now he has not seen or caught any, proving that they have become extinct in this part, or driven further back’.[49]

Hut in the Vale of Belvoir. AW Lord photo from the Weekly Courier, 20 July 1922, p.22.

Benefiting from Etchell’s advice, and using Thompsons Park on the Surrey Hills block as another base, the government party, consisting of Sergeant MA Summers, Trooper Higgs, Roy Marthick from Circular Head and Dave Wilson, the VDL Co’s manager at Ridgley, scoured the region near Mount Tor, around the head waters of the Leven, the Vale of Belvoir and the Vale River down to its junction with the Fury and the Devils Ravine without finding signs of thylacine activity. A further search was conducted around the Pieman River goldfield and the coast north-west of there.[50] After commenting on the large numbers of brush possums in the area searched, Summers arranged for Etchell to secure seven pairs of black possums for the Healesville Sanctuary, Victoria.[51] Again, in 1941, Etchell advised that on the Surrey Hills, ‘the kangaroo and wallaby are plentiful … and that open season would be beneficial for everyone.[52]

There were bumper hunting seasons near the end of World War II and after it, with £15,000-worth of skins sold at the sale at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, more than 32,000 skins offered there in 1944 and record prices being paid at Guildford in 1946.[53] One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins for sale in 1943.[54] Taking advantage of high demand, in 1943 the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue—these included Painter Run (Painter Plain), Park Run (Old Park?), Mayday Run (Mayday Plain, now First of May Plain, in the furthest south-east corner of the Surrey Hills block), Talbots Run (presumably near Talbots Lagoon), Peak Run (Peak Plain), Black Marsh Run (probably near the site of the old Burghley Station), and those which probably corresponded to the mileposts on the Emu Bay Railway, the 25 Mile, 36 Mile and 46 Mile Runs. Like the traditional Cornish ‘tribute’ mining system, by which parties of men competed to work particular sections of a mine, the highest bid won the contract for each run. Men paying as much as £70 for seasonal rental of a run felt short-changed when heavy snowfalls curtailed their activities, which were still subject to the official hunting season. Nearly all the men who hunted the Surrey Hills block in 1943 combined this work with pulp wood cutting for Australian Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) at Burnie, or another job in the timber industry. Waratah’s Trooper Billing estimated that pulp wood cutting averaged seven hours per day, compared to 16 hours per day for snaring.[55] Billing regarded the Surrey Hills block as a game-breeding ground which damaged the interests of adjacent landholders.[56]

Luke Etchell posing before the Guildford skin sale in 1946. Winter photo from the Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

These bumper seasons were the end of the road for the Etchell brothers. Thomas Etchell died in September 1944.[57] Brother Luke was still snaring at 78 years of age in 1946, when the Burnie photographer Winter posed him in best suit, that apparently being the outfit of choice for hauling your skins on your shoulder to the Guildford sale.[58] Luke Etchell died in Hobart on 8 June 1948.[59] There were a few good hunting season after that, but in 1953 new regulations curbed an industry already reduced by weakening European and North American demand for skins. The era of the hunter-stockman and the professional bushman—the man who could live by his nous in the bush—was drawing to a close.

[1] ‘Van Diemen’s Land Company’, Hobart Town Courier, 25 September 1835, p.4.

[2] Edward Curr to Joseph Fossey, Woolnorth manager, 12 May 1830, VDL23/3 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office [henceforth TAHO]).

[3] Edward Curr to James Reeves, Woolnorth manager, 2 April 1831, VDL23/4 (TAHO).

[4] Court of Directors to JH Hutchinson, Inward Despatch no.98, 10 October 1833, VDL193/3 (TAHO).

[5] See Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 8 February 1836, 30 June 1836, 10 August 1836, 14 September 1836 and 1 February 1837, VDL23/7 (TAHO).

[6] Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, Woolnorth manager, 6 March 1835, VDL23/6 (TAHO).

[7] For an overview of James Lucas’ work for the VDL Co, see Robert Paddle, The last Tasmanian tiger: the history and extinction of the thylacine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2000.

[8] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[9] VDL232/1/5, p.158 (TAHO).

[10] VDL232/1/5, p.215 (TAHO).

[11] VDL232/1/5, p.255 (TAHO).

[12] VDL232/1/5, p.272 (TAHO).

[13] HW Wheelwright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[14] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

[15] James Wilson to James Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Notices to correspondents’, Launceston Examiner, 26 November 1879, p. 2; ‘Kangaroo hunting’, Cornwall Chronicle, 31 January 1879, p. 2.

[17] John Etchell was tried at the Derby Assizes 15 May 1843 for housebreaking, stealing money and assault, see CON33/1/53. http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-53,308,90,F,60 accessed 18 December 2016.

[18] Matthias Gaunt, ‘Indulgence’, Launceston Examiner, 1 December 1849, p.4.

[19] Birth registration 702/1869, Horton.

[20] Luke’s mother, Mary Ann Etchell, died at Waratah in 1903 (‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 October 1903, p.2).

[21] See file (SC195-1-57-7410, p.1) at https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=john&qu=etchell# accessed 18 December 2016.

[22] ‘Mining intelligence’, Launceston Examiner, 28 September 1878, p.2. See also Charles Sprent’s dismissal of John Etchell’s alleged tin discovery at Brickmakers Bay in 1873 (Charles Sprent to James Norton Smith, 6 July 1873, VDL22/1/4 [TAHO]).

[23] ‘Stanley’, Mercury, 12 August 1880, p.3.

[24] ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.

[25] See Nic Haygarth, ‘William Aylett: career bushman’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.28–55.

[26] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 26 February 1880, p.4.

[27] Luke and Flora Etchell were convicted of stealing potatoes at Black River in 1883 (‘Emu Bay’, Reports of Crime, 20 April 1883, p.61; ‘Miscellaneous information’, Reports of Crime, 4 May 1883, p.70). Luke’s sister Sarah Ann was convicted of concealing the birth of a still-born child in pathetic circumstances in Waratah (‘Supreme Court’, Daily Telegraph, 22 August 1884, p.3). The most serious matter was his brother Thomas Etchell’s conviction of indecent assault in Waratah (‘Supreme Court, Launceston’, Mercury, 19 February 1896, p.3).

[28] ‘The Corinna fatality’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 3 November 1900, p.4.

[29] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 July 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 November 1900, p.2; ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 August 1905, p.2. In December 1900 Williams exhibited the skin of a tiger said to be seven feet long in Burnie (‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 25 December 1900, p.2). For another Williams tiger story, see ‘Inland wires’, Examiner, 14 December 1900, p.7.

[31] Potential Williams bounties: no.344, 17 November 1899 (’10 October’); no.1078, 11 September 1902 (’31 July 1902’); no.1280, 2 December 1902; no.76, 20 February 1903 (’14 February 1903’), (’17 March 1902’). Etchell bounty: 25 June 1903, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[32] J North, ‘A Waratah man’s opinion’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[33] ‘Local government: Waratah’, Daily Telegraph, 9 March 1910, p.7.

[34] ‘Tanner’s licences’, Police Gazette, 9 August 1912, p.183.

[35] For snaring see, for example, Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 16 July 1911, VDL22/1/47 (TAHO). For buying see for example, ‘Alleged illegal buying of skins’, Advocate, 27 July 1939, p.2.

[36] For the police raid, see Sergeant Butler to Superintendent Grant, 10 May 1937, AA612/1/12 (TAHO). See also ‘Trappers defrauded’, Mercury, 3 September 1930, p.9; and ‘Conspiracy charge’, Mercury, 4 September 1930, p.10. In 1943 police interviewed Harold Reuben Etchell in Wynyard but failed to find any illegally obtained skins (Detective Sergeant Gibbons to Superintendent Hill, 14 September 1943, AA612/1/12 [TAHO]).

[37] ‘Sheffield’, Advocate, 21 September 1937, p.6.

[38] See HS Allen to AK McGaw, 25 October 1907, VDL22/1/39 (TAHO). Thomas Etchell went osmiridium mining in 1919 during the peak period on the western field (see Pollard to the Attorney-General’s Department, 19 November 1919, p.113, HB Selby & Co file 64–2–20 [Noel Butlin Archive, Canberra]).

[39] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 20 February 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[40] George E Brown to AK McGaw, 27 June 1912, VDL22/1/48 (TAHO).

[41] Police Department, Report for 1925–26 to 1927–28, Parliamentary paper 41/1928, Appendix J, p.13.

[42] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, the author, Somerset, Tas, 1992, pp.47–48.

[43] ‘Owes his life to dog’, Advocate, 13 July 1932, p.8; ‘Lost in snow for fortnight’, Advocate, 27 June 1932, p.4.

[44] VDL Co annual report 1934, Miscellaneous Printed Matter 1880‒1967, VDL334/1/1 (TAHO).

[45] T Etchells [sic], ‘Open season for game’, Examiner, 5 May 1934, p.11.

[46] ‘Personalities at the show’, Examiner, 7 October 1936, p.6. Ironically, one of his tasks now was to keep other hunters off the company’s land (see, for example, advert, Advocate, 18 January 1834, p.7) in case they endangered stock or let stock out through an open gate.

[47] MY Donovan to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, 12 January 1937, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[48] MA Summers’ report, 3 April 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[49] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[50] MA Summers’ report, 14 May 1937, AA612/1/59 H/60/34 (TAHO).

[51] ‘Opossums for Melbourne’, Advocate, 26 May 1938, p.6.

[52] Luke Etchell, ‘The game season’, Advocate, 15 May 1941, p.5.

[53] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4; ‘Over 32,000 skins offered at sale’, Advocate, 13 September 1944, p.5; ‘Record prices at Guildford skin sale’, Advocate, 30 July 1946, p.6.

[54] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4.

[55] Trooper Billing to Superintendent Hill, Burnie Police, 14 August 1943, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[56] Trooper Billing to Superintendent Hill, Burnie Police, 14 August 1943, AA612/1/5 (TAHO).

[57] ‘Thanks’, Advocate, 26 September 1944, p.2.

[58] ‘Still trapping at 79’, Examiner, 1 August 1946, p.1.

[59] ‘Deaths’, Advocate, 12 June 1948, p.2; ‘Mr Luke Etchell’, Advocate, 1 July 1948, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 17/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

The Wainwrights at Mount Cameron West (now returned to the Aboriginal people, as Preminghana) during the late 1890s. Sunday best is adopted for the photographer. The girl standing at front beside her parents Matilda and George is probably May, the boys on horseback are probably George, Dick and Harry. Photo courtesy of Kath Medwin.

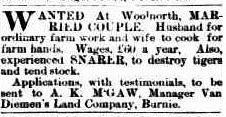

In 1889 Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) local agent James Norton Smith advertised for ‘a trustworthy man to snare tigers [thylacines or Tasmanian tigers], kangaroo, wallaby and other vermin at Woolnorth’, the company’s large grazing property at Cape Grim. The annual wage was £30 plus rations and a £1 bounty for each thylacine killed.[1] Applications came from Tasmanian centres as far afield as Branxholm in the north-east and New Norfolk in the south. One, written on behalf of her husband, came from Rachel Nichols of Campbell Town. She was the mother of then eleven-year-old Ethelbert (Bert) Nichols, the future hunter, Overland Track cutter, highland guide and Lake St Clair Reserve ranger.[2]

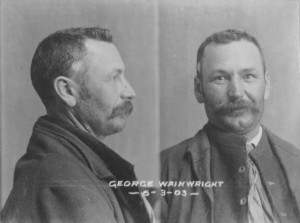

However, none of these applicants got the job. The man chosen as ‘tigerman’, as the position was known within the VDL Co, was George Wainwright senior, who arrived ‘under a cloud’ as George Wilson and departed in 1903 when convicted of receiving stolen skins.[3] Was he a relation of Woolnorth overseer James Wilson, or how was he selected for the job?[4] And what was a tigerman anyway?

George Wainwright was born in Launceston in 1864, and seems to have a not untypical upbringing for the poorly educated child of an ex-convict father, featuring family breakdown, petty crime, shiftlessness and suggestions of poverty.[5] As a young adult he measured only 162 cm (5 foot 3 inches), with a dark complexion and dark curly hair. The scar under his chin may have the result of rough times on the streets of Launceston.[6] Food may have been scarce. At thirteen he faced court with another boy on a charge of stealing apples (the case was dismissed for lack of evidence).[7] In 1883, his employer, Launceston butcher Richard Powell, had the nineteen-year-old arrested on warrant (that is, in absentia) on a charge of breaching the Master and Servant Act.[8] He had run off to Sydney, describing himself as a cook.[9]

George had returned to Launceston by October of that year, when his mother, now known as ‘Mrs T Barrett’ (née Caroline Hinds or Haynes or Hyams), ran a public notice instructing clergymen not to marry her son to anyone, he being under age.[10] Presumably George had Matilda Maria Carey (1863–1941)—or her pregnancy—in mind, because the couple were soon united, and soon separated.[11] In 1885 Matilda prosecuted George for deserting her and George junior, having not sent her any money for six months. It was revealed in court in Melbourne that George had recently been a grocer’s assistant, but now was working in a Brunswick (Melbourne) brick yard. Matilda Wainwright was then living with her father-in-law William Wainwright in Launceston. She claimed he showed her little sympathy, having sold all her furniture and told her to seek a living for herself. George Wainwright was freed on agreeing to pay her 10 shillings per week.[12]

Interestingly, in Victoria he was known to police as George Brown, ‘alias Wainwright’.[13] Presumably he returned to Launceston sometime between 1885 and 1889—and changed his name to George Wilson! He may have been the George Wilson who was in Beaconsfield in 1886 and 1887.[14] Perhaps he became a protégé of James Wilson, the Woolnorth overseer, and perhaps that man’s intervention secured Wainwright/Brown/Wilson the tigerman job at Woolnorth. James Wilson had coined the term ‘tigerman’ to describe the Mount Cameron West shepherds in the period 1871–1905. Convinced that thylacines were killing their sheep, the VDL Co gave the Mount Cameron West man the additional job of maintaining a line of snares across a narrow neck of land at Green Point, which was believed to be the predator’s principal access point to Woolnorth. Otherwise, the tigermen were actually standard stockmen-hunters, charged with guarding sheep and destroying competitors for the grass.

George Wilson and his family originally occupied a one-room hut at Mount Cameron West. In 1893 George Wainwright, as he was now known again, apparently told a visitor that he received £2-10 for each thylacine killed—£1 from the VDL Co, £1 from the government and 10 shillings for the skin. In the years 1888–1909 the Tasmanian government paid a bounty on every thylacine carcass submitted to police. However, nobody by the name of Wainwright ever collected a government bounty: in fact only two VDL Co tigermen, Arthur Nicholls and Ernest Warde, personally collected government bounties while working for the company.[15] The thylacine carcasses appear to have been sold through intermediaries, chiefly Stanley merchants Charles Tasman (CT) Ford (1891–99) and (after Ford’s death) William B (WB) Collins (1900–06). Ford, who also drove cattle down the West Coast to Zeehan and bought VDL Co stock, was a regular visitor to Woolnorth.[16]

In 1893 Wainwright had about 60 springer snares set for wallaby, pademelon and brush possum.[17] Ringtails were the dubious beneficiary of technological change, as the commercial manufacture of acetylene or carbide during the 1890s revolutionised ‘spotlighting’. Using an acetylene lamp to spotlight nocturnal animals was a vast improvement on the traditional method of shooting by moonlight, since some animals, especially the ringtail possum and ‘native cat’, were ‘hypnotised’ by the lamp, remaining rooted to the spot. It was not the ideal hunting technique for a grazing run, however, let alone for a solitary shepherd. Usually, two men worked together, one ‘spotting’ the animals with the acetylene lamp, the other shooting them. The lamps which shooters used frightened stock, and sometimes shooters’ dogs ran amok with grazing sheep. More significantly for the hunter, shooting the animal in any other part but the head damaged its pelt. Acetylene fumes were also unpleasant for the hunter, and the battery sometimes gave him an unexpected ‘charge’.

More money was available for a living tiger than a dead one. By Wainwright’s time, thylacines were in demand from zoos. In 1892 James Denny caught one alive at the Surrey Hills and sent it to the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne.[18] In 1896 CT Ford was asked to procure live tigers for a circus. Wainwright obliged by capturing a thylacine alive and sending it into Stanley, where there was ‘a little excitement … to see “the tiger”’ before it was shipped to Sydney.[19] This thylacine capture does not appear in the extant Woolnorth farm journal record (the journal for 1896 is missing) or in any other surviving official records for Woolnorth. Since the animal was not killed, Wainwright received no VDL Co or government reward for it.

In 1897–98 a new hut was built for George and Matilda at Mount Cameron. They would need it. Six children—George, Alf, Dick, May, Harry, Gertrude and Robert—gave them plenty to worry about in such an isolated place. If that was not enough, Matilda was reportedly ‘very ill’ in July 1893 and ‘badly hurt’ in January 1894, while in May 1900 Woolnorth overseer W Pinkard had to fetch medicine for her from Stanley.[20]

By 1900 George and Dick were already showing their prowess as tiger snarers, and one of the Wainwright boys was digging potatoes.[21] With their father sometimes helping out elsewhere on the property, fetching cattle from Ridgley or a stockman from Trefoil Island, the children quickly developed a range of skills which ensured that they could work on the land independently.[22]

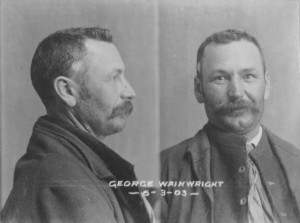

George Wainwright’s mugshot, 1903. Courtesy of TAHO.

Wainwright’s imprisonment in 1903 gave them that opportunity. The story of his crime of receiving 298 wallaby, 298 pademelon, 17 tiger cat, 2 domestic cat and 10 brush possum skins stolen from William Charles Wells contains insight into hunting at Mount Cameron West and on Woolnorth generally. Wells was caretaker (hunter-stockman) for a farm at Green Point south of Woolnorth, near where the VDL Co arranged its snares. The owner of the property, Thomas John King, had stayed with Wainwright in the Mount Cameron Hut in July 1902 after fetching the skins from the farm. The skins disappeared overnight after being left outside the hut in a cart. Suspicion fell on Wainwright not only because his was the only hut in the area but because he had previously tried to buy the skins at a price which was refused. Police alleged that in September Matilda Wainwright drove a buggy containing the skins to the port at Montagu to be loaded on the ketch Ariel.[23] It was now close season, so Wainwright wrote telling Stanley storekeeper WB Collins that he was sending down some out-of-season skins and suggesting that he ask the police to let them pass. Wells claimed to have identified 23 of his stolen skins in Collins’ store.[24] Proof that Wainwright was guilty centred on Wells’ identification of an unusually light skin among those Wainwright had sent to market. A search conducted among the skins of three Launceston skin merchants, Lees, Sidebottom and Gardner, revealed only three or four skins matching the one identified by Wells, confirming the distinctiveness of the skin and strengthening the case against Wainwright.[25]

Launceston merchant Robert Gardner testified that he had known Wainwright for 25 years, having employed him when he (Wainwright) was a boy, and that he had done business with him for several years, finding him straightforward and honest. He had bought wallaby skins from Wainwright regularly.[26] Despite this testimonial, Wainwright was given a twelve-month sentence for receiving stolen property. Thirty-nine years old, he died in the Hobart Gaol of heart failure prompted by acute pneumonia only four months into that sentence.[27]

Today a relatively young man’s death in custody would provoke an inquest. However, the harshness of Wainwright’s demise seems in keeping with the harshness of his sentence and the general torpor of working people’s lives more than a century ago. George must have done something right as a hunter and provider, because he left wife Matilda £305—more than ten times his annual stockman’s wage.[28]

Charged with nothing, Matilda Wainwright stayed on as cook at Woolnorth, although only because no one else could be found for the job. ‘I would have preferred anyone else rather than Mrs Wainwright’, new VDL Co agent AK McGaw lamented, ‘and now that she is there I am not altogether satisfied that her influence is for the best. Of course I find her appointment does not answer I will have no hesitation in terminating it’.[29] McGaw had advertised for a married couple to replace the Wainwrights.[30] He effectively got one when the widowed Matilda married the new overseer, Thomas Lovell, while her sons, good workmen, also had a future at Woolnorth. As a woman and mother, remarriage was her only option anyway. George Wainwright junior would carve out his own long career as a VDL Co stockman.

[1] ‘Wanted, at Woolnorth’, Daily Telegraph, 9 August 1889, p.1.

[2] Rachel Nichols to James Norton Smith, 8 August 1889, VDL22/1/19 (Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office [afterwards TAHO]).

[3] AW McGaw, Outward Despatch no.16, 1 June 1903, p.151, VDL7/1/13 (TAHO); ‘Death of a prisoner’, Mercury, 15 July 1903, supplement p.6.

[4] On the bottom of J Lowe’s application for the job is written in pencil ‘Geo Wilson also’. Everett was the reserve choice: on the back of his application is written ‘If man, at present engaged—not successful will write JL again’. See J Lowe application 9 August 1889 and J Everett application, 19 August 1889, VDL22/1/19 (TAHO).

[5] For William Wainwright (1810–87), see conduct record, CON33-1-90, TAHO website, http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-90,207,205,F,60, accessed 17 December 2016.

[6] ‘Miscellaneous information’, Victoria Police Gazette, 19 August 1885, p.232.

[7] Birth registration 60/1864, Launceston; ‘Police Court’, Cornwall Chronicle, 7 February 1877, p.3.

[8] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Tasmanian, 22 April 1882, p.432; ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 7 February 1883, p.3.

[9] He arrived in Sydney from Launceston on the Esk, 9 February 1883, New South Wales, Australia, Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1826–1922.

[10] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 31 October 1883, p.1.

[11] Marriage registration 677/1883, Launceston. They married 7 November 1883, George William Wainwright was born seven months later, on 12 June 1884, birth registration 371/1884, Launceston. Matilda Maria Carey was born in Launceston, 22 December 1863, registration 23/1864, Launceston.

[12] ‘Wife desertion’, Launceston Examiner, 29 August 1885, p.2.

[13] ‘Miscellaneous information’, Victoria Police Gazette, 19 August 1885, p.232.

[14] ‘Beaconsfield’, Daily Telegraph, 29 May 1886, p.3; ‘Beaconsfield’, Launceston Examiner, 15 January 1887, p.12.

[15] Nicholls: bounties no.289, 14 January 1889, p.127; and no.126, 29 April 1889, p.133, LSD247/1/1. Warde: bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, p.325, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] James Wilson to JW Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[17] Austin Allom, ‘A trip to the west coast’, Daily Telegraph, 19 August 1893, p.7.

[18] ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 17 September 1892, p.2.

[19] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[20] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 10 July 1893, VDL277/1/20; 22 January 1894, VDL277/1/21; and 7 May 1900, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[21] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 13 and 14 June, 7 May 1900, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[22] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 22 September 1898, VDL277/1/24; 16 January and 5 March 1899, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[23] ‘Supreme Court’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 14 November 1902, p.2.

[24] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 15 November 1902, p.3.

[25] ‘The Wainwright case’, Examiner, 28 February 1903, p.6.

[26] ‘The Wainwright case’, Examiner, 27 February 1903, p.6.

[27] ‘Death of a prisoner’, Examiner, 15 July 1903, p.6.

[28] ‘Testamentary’, Mercury, 20 October 1903, p.4.

[29] AK McGaw to VDL Co Board of Directors, no.38, 2 November 1903, p.313, VDL7/1/13 (TAHO).

[30] Advert, Examiner 20 May 1903, supplement p.8.

by Nic Haygarth | 10/12/16 | Britton family history, Circular Head history

Winching a log out of the Welcome Swamp, 1923. From the Weekly Courier, 6 September 1923, p.21

Another shot of Welcome Swamp drainage, a familiar scene on the dolomite swamps of Circular Head in the first half of the 20th century. From the Weekly Courier, 6 September 1923, p.21.

The rapaciousness of the Circular Head timber industry was captured in Bernard Cronin’s novel Timber Wolves, published in 1920, the year before the establishment of the Tasmanian Forestry Department in an effort to make the industry sustainable. Mainland timber contractors and local operators tried to squeeze out competitors by securing strategic leases in front of existing working leases, cutting off transport routes and making expansion impossible:

‘Did you ever hear of “dummying”? These timber wolves go to the limit [of their timber quota] in their own names and put up dummy agents to cover the rest. It’s illegal, but what does that matter. They’s [sic] no one ever asts [sic] the question so long as the rental and royalties and so on are paid regularly. The while system is rotten to the core … We got to take the price they offer us, or let the timber rot …’[1]

Conservator of Forests Llewellyn Irby read Timber Wolves before visiting Smithton in 1922. ‘This is the worst place in Tasmania for toughs’, he wrote

and is part of the locality referred to in ‘Timber Wolves’ so you can imagine what we have to deal with. We have had a lot of trouble with a chap who is the worst scoundrel in the district. He has the reputation of being a man eater, has nearly killed two men by kicking them when down, while two or three others go through life minus half an ear, a piece he has bitten off.

This was Bill (William Henry) Etchell, whom Phil Britton described somewhat tactfully as ‘a notorious strong man, opportunist leader of men, hard drinker’. According to Phil, Etchell would pay his men well, then win back much of their wages in card games at the pub. Irby feared stronger tactics:

As he was looking for me I felt a tingling in my ears and as when drunk he is absolutely murderous and we had seized his logs; I carried my gun … if they are the ‘Timber Wolves’ we are the forest bloodhounds and intend to clean them up …[2]

Nor were rough tactics restricted to sawmillers. By 1921 the success of the Mowbray Swamp reclamation had convinced the government to drain the Welcome, Montagu, Brittons and Arthur River Swamps. The Surveyor-General stressed the importance of reclaiming

a large area of swamp lands, now lying in useless waste, but which when reclaimed and opened up will form one of the largest and best agricultural and dairying propositions in the state.[3]

Disappointment followed. The development of the Smithton dolomite Welcome Swamp near East Marrawah (Redpa) was a comparative disaster. Drainage was inadequate, the scheme was extremely expensive, and superintendent of the works, Thomas Strickland, faced accusations of foul play. Strickland resigned with the job incomplete after being criticised by a Royal Commission into the reclamation scheme.[4] For years afterwards no land on the Welcome Swamp was ploughed.

Harvesting blackwood by bullock team near Smithton. From the Tasmanian Mail, 12 September 1918, p.19.

The summer of 1923–24 was so wet that it was impossible to haul logs out on flat land by bullock team, reducing productivity, but by February 1924 the bush was drying out. ‘We may have to get a bullock driver ourselves’, Mark Britton told Jim Livingstone, ‘as you cannot depend on CW [Charlie Wells] …’ Wet weather also prevented laying down more tramway, so the chance was taken to overhaul the locomotive instead. With blackwood hard to remove from the bush, attention was switched to cutting hardwood from Robinson’s land, where tracks were opened up for the winder to work. Brittons also applied to remove blackwood from a block of crown land which they believed could only be reached by log hauler from spur lines on their own lease. At least £30 of work was done in anticipation of gaining the lease—only to discover it had been granted to Frank Fenton, one of the sons of CBM Fenton and a grandson of James Fenton, pioneer settler at Forth. He was a new player in the timber game who had built a steam sawmill at the foot of the Sandhill. Mark Britton continued:

We do not know if Fenton knows about it [the blackwood on his lease] anyway we do not intend to tell him at present … some of the mills are going bung around here and more will follow we are thinking soon.[5]

Mark Britton (with beard), Arthur Coates, Pat Streets, H Shaw and another man loading dry blackwood boards.

To Mark, as he explained to Llewellyn Irby, this was a clear case of dummying by Fenton. He went on to explain that there was no longer enough timber on Crown land to keep a small mill cutting for three months of the year. Brittons could have attacked the disputed blackwood by steam hauler. Fenton could not, making it impossible for him to obtain the whole of the timber.[6] Not only would timber be wasted, Mark claimed, but Fenton’s method of removing the timber could destroy roads designed for lighter traffic and built by men working legitimately.[7]